eBook - ePub

Being Reflexive in Critical and Social Educational Research

- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Being Reflexive in Critical and Social Educational Research

About this book

This text is a collection of case studies and readings on the subject of doing research in education. It takes a personal view of the experience of doing research. Each author presents a reflexive account of the issues and dilemmas as they have lived through them during the undertaking of educational research. Coming from the researcher's own perspectives, their positions are revealed within a wider space that can be personal, political, social and refexive. With this approach, many issues such as ethics, gender, race, validity, reciprocity, sexuality, class, voice, empowerment, authorship and readership are given an airing.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Being Reflexive in Critical and Social Educational Research by Geoffrey Shacklock,John Smyth in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

EducationSubtopic

Education General1

Behind the ‘Cleansing’ of Socially Critical Research Accounts

John Smyth and Geoffrey Shacklock

Why This Collection?

The idea for this collection on being reflexive about critical educational and social research, came from conversations we had on the personal struggle of doing research, and writing accounts of those struggles. In the first instance, these conversations were pedagogical because of their focus on researching the process of placing closure on a dissertation. Later, the conversations became more concerned about the absence of such commentaries. It became clear that it was often difficult to find an account of the complexities of doing critical research, written by a researcher who could construct the account out of a critical appraisal of their own work.

We saw a need for deeply personal and individual readings of ‘the experience of critical research’ in educational and social settings. We saw a need for individual researchers to present accounts of the experience of the critical research act using reflective postures that challenged why one course of action was taken from among a range of possibilities. Such accounts, we thought, should focus upon those issues and dilemmas which caused trouble and uncertainty in the research process. As we saw it, such accounts would tell the story about the intersection of the critical research perspective and the particular circumstances of the research context, as they occur in the actual experience of doing critically-oriented research.

This collection is therefore grounded in the primacy of the reflexive moment in critical forms of research. Each account develops through expressions, self-reflections about the researcher’s struggle with the epistemological, methodological, and political issues that are always inherent in critical qualitative research in educational and social settings. We believe those accounts provide the ‘personal’ dimension that links the theoretical discourse of socially critical research and its methodological imperative, to the particular research act. These portrayals are an explicit recognition of the impact of the researcher on the intentions, processes and outcomes of the research.

We have tried to assemble a collection that fills a space in accounts of critical educational and social research; sometimes referred to as the phenomenon of the ‘missing researcher’. The reflexive narratives of researcher’s encounters with the intersections between the researcher’s values and the research processes reintroduces the researcher as person into the account. Issues like: ethics, gender, race, validity, reciprocity, sexuality, voice, empowerment, authorship, and readership can be brought into the open and allowed to ‘breathe’ as important research matters.

We see these reflexive readings on critical research as important windows on the tensions between: epistemology and methodology, critical theory and post-modern thinking, and scientism and politicization, experienced by critical qualitative researchers. Many of the important issues that critical researchers face in their work are exposed in a way that says: ‘I too know how it feels to do this kind of research’.

Contributors open up how they went about the task of dealing with the uncertainties of bringing a critical research project from conception to completion. These contributions are about the (in)/visibility of thickness-thinness between the two sides of the theory-practice coin. In other words, that aspect of the research process which usually has great volume but low surface area — its substance is always high for the researcher(s), but its visibility is often low for the research (product) audience.

What we have in the contributions to the book, is ‘rendition-exposure’ that allows others to experience something of the struggle and excitement of the research act. In Eisner’s (1979, 1991) terms, the contributors have engaged in acts of research ‘connoisseurship’; they have presented personal insights of the research act as part of an examination of their own research experience. They give expression to inner dialogue that generally exists only as a sub-text in parts of a research account. We believe that these reflexive accounts give valuable readings of researcher understanding of how complexity in research is understood by researchers themselves.

What Do We Mean by Critical Research?

There are some misconceptions as to what constitutes critical research; for example, that its emphasis is negative or carping, or that it is somehow committed to faultfinding. Readings like this are give-aways that those making them have not read themselves into the meaning of ‘critical’ as expressed in the sociological literature.

One of the more concise straightforward explanations of what it means to operate critically has been provided by Robert Cox (1980), when he said: ‘[To be critical is to] stand apart from the prevailing order of the world and ask how that order came about’ (p. 129). Cox argues that the place of theory is neither incidental nor unimportant in this, and that theory can be regarded as serving two possible purposes. The first view of theory is that it is a guide to help solve problems posed within a particular perspective. This view of theory ‘takes the world as it finds it…with the prevailing social and power relations and institutions into which they are organized, as the given framework for action’ (ibid, p. 128). The second set of views about theory, is that its purpose is to ‘open up the possibility of choosing a different valid perspective from which the problematic becomes one of creating an alternative world’ (idid, p. 128). Depending upon which purpose we opt for, theory will have quite a different meaning. While for both approaches the starting point is some aspect or instance of human activity, the orientation to the relationship between the parts and the whole is quite different in each case. From a problem-solving perspective, the approach is one that ‘leads to a further analytical sub-division and limitation of the issues to be dealt with…’ (ibid, p. 129). In the case of critical theory, the approach is one which ‘leads towards the construction of a larger pictureof the whole of which the initially contemplated part is just one component, and seeks to understand the processes of change in which both parts and whole are involved’ (ibid, p. 129). This is a distinction which is fundamental to the chapters contained in this book.

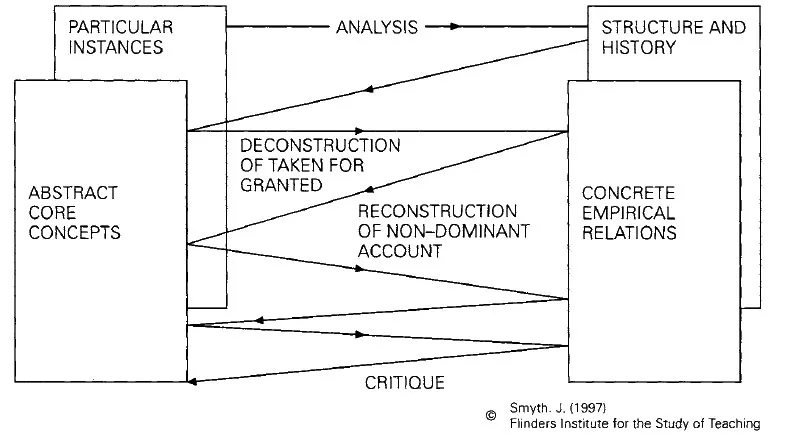

Figure 1.1: Critical social research

Source: Adapted from Harvey (1990)

Another way of speaking about this is in terms of the dialectical relationship between particular instances, concrete empirical relations, abstract core concepts, and structure and history. Harvey (1990) speaks about critical research as cutting through ‘surface appearances’ (p. 19) by locating the issues being investigated in their historical and structural contexts. Critical research, as Harvey argues, continually engages in an ongoing conversation, analysis and critique of these elements, starting from the position that the object of study is not “‘objective” social appearances’ (ibid). Phenomena, from a critical vantage point, are not considered to stand on their own but are implicated, embedded and located in wider contexts that are not entirely innocent. Furthermore, such structures are ‘maintained through the exercise of political and economic power’ which is ‘legitimated through ideology’ (ibid, p. 19). Research of this kind raises serious questions about ‘who can speak?’ (Roof and Weigman, 1995).

Critical research then, is centrally concerned with the simultaneous process of ‘deconstruction’ and ‘reconstruction’. It works something like this. Within a piece of research, some core abstract concepts are located which are considered to be central; they are used repeatedly to interrogate situations of concrete lived reality in order to develop a new synthesis. In this sense, theory is not, therefore, simply ‘abstract analysis’ nor is it something merely to be tacked onto data at the end of some process of analysis; rather, what occurs is a theory-building process involving:

…a constant shuttling backwards and forwards between abstract concept and concrete data; between social totalities and particular phenomena; between current structures and historical development; between surface appearance and essence; between reflection and practice. (Harvey, 1990, p. 29)

The intent is to engage in a constant questioning and building up of theory and interpretations through repeated ongoing analysis until a coherent alternative reconstruction of the account is created. As Harvey notes, the selection of a ‘core’ concept is not a final or a single instance; ‘it only emerges in the course of the analysis…and it is only “correct” in the sense that it provides…the best focus [at that time]’ (ibid, p. 30). In many respects, this genre of research is conversational in that there is constant dialogue between core concepts and data about fieldwork situations. It amounts to a kind of ‘negotiating the question’ (Roof and Weigman, 1995, p. x) in that what is worthwhile saying or pursuing can never be stated definitively, but only as a consequence of having commenced some inquiry, discussion or conversation. It is very much a case of ‘conversation begins in response, not in a speaker’s singular assertion’ (ibid).

What Will This Book Add to the Field of Critical Research?

Engaging in critical research of the kind generally described above, and undertaken elsewhere by the contributors to this book, involves a number of what Lather (1992) calls ‘critical frames’. These might be taken to include aspects like the following:

- studying marginalized or oppressed groups who are not given the authority to speak;

- approaching inquiry in ways that are interruptive of taken-for-granted social practices;

- locating meaning in broader social, cultural and political spheres;

- developing themes and categories from data, but treating them problematically and as being open to interrogation;

- editing the researcher into the text, and not presuming that she/he is a neutral actor in the research;

- being reflexive of its own limitations, distortions and agenda;

- concerned about the impact of the research in producing more equitable and just social relationships (Smyth, 1994).

Given that much of the work that is the subject of reflection in this book comes from researchers who have undertaken some version of critical ethnography (although not all would describe it in that way), we would do well to attune ourselves to some of the difficulties articulated by ethnographers generally.

Pearson (1993) makes the point that: ‘ethnography is a messy business, something you would not always gather from many of the “research methods” texts which deal with the subject’ (p. vii). What Being Reflexive does, like Hobbs and May’s (1993) book that engages authors in getting behind previously published interpretive ethnographic accounts, is to offer a variety of accounts (albeit from the socially critical domain) by researchers who have similarly described ‘the difficulties which can (and do) arise when researchers attempt to “immerse” themselves in other people’s lives’ (Pearson, 1993, p. vii). Like Pearson we started from the vantage point that:

Published accounts of fieldwork are invariably cleansed of the ‘private’ goingson between researcher and researched. When the lid is taken off, however, this can be something of a shock, (ibid, p. vii)

Both Hobbs (1993) and May (1993) attest to their feelings about the changed relationship they experienced once the fieldwork was completed and the text ‘concluded’ — a point made by most of the authors in this volume. It is what occurs after the account has been ‘sanitized’ that can often be the most revealing, for, as Hobbs (1993) notes, the original pass at codifying the procedure by which the research was done invariably masks and conceals much:

It seeks to neatly dissect the research process, packaging its various components into self-contained, hermetically sealed units bonded with a common epistemology. (p. 46)

Yet, the reality for many researchers is that ‘changes…take…place outside the sanctified confines of the fieldwork’ and that ‘our experiential and interpretive faculties continue to function long after the gate to the field has been closed. Funding may have been turned off but intellectual work keeps flowing’ (ibid, p. 48). For May (1993) the challenge here is to ‘invert the hidden equation’ where the equation is ‘feelings=weakness’ (ibid, p. 76). He says, the myth ‘is perpetrated whereby personal feelings (read as “inaccurate” or “untrue”) during ethnographic research are typically viewed as impediments to good practice and analysis’ (ibid, p. 72). May concurs with Hammersley and Atkinson (1983) that: ‘Rather than engaging in futile attempts to eliminate the effects of the researcher, we should set about understanding them’ (1993, p. 75).

With this set of considerations in mind, we see the contribution of this book as building upon the work of writers like: Quantz (1992) and McLaren and Giarelli (1995) in education, and Morrow and Brown (1994), Harvey (1990), and Burawoy et al. (1991) in critical social science more generally. We also see the book, in part, as an indirect rejoinder to Hammersley (1995) who seems to be confused aboutwhether there is such a tradition, who has contributed to it, the basis for its claims, and the manner in which socially critical research can make a contribution. While we certainly agree with Hammersley that there are a ‘range of conceptions of the “critical”’ (p. 35), we are much less inclined to be dismissive or to agree that ‘there are no grounds for advocating a distinctively “critical” form of social research’. That Hammersley has been so insistent and diligent in his refusal, suggests that there is indeed something of substance that is the object of his critique.

What do we Mean by Reflexivity?

Reflexivity in research is built on an acknowledgment of the ideological and historical power dominant forms of inquiry exert over the researcher and the researched. Self-reflection upon the constraining conditions is the key to the empowerment ‘capacities’ of research and the fulfilment of its agenda. It would be fair to say that, what some call the ‘ideal’ position of researcher as found in the dominant position of the social sciences, based in the collection of neutral fact-like data, and the subsequent formulation of law-like propositional knowledge about social life, permeates epistemological understandings and methodological groundings for all research. Realistically, researchers operating out of a critical perspective are not immune to the effects of technical cognitive interests which structure knowledge and understandings about ethics, power, politics, reliability, and validity in research. However, the emancipatory cognitive interest (Habermas, 1971) of the critical perspective yields a medium for the exposure of ideological constraints on the research, through reflexivity. We believe that a researcher can, through the possession of critic...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Acknowledgments

- Series Editor’s Preface

- 1 Behind the ‘Cleansing’ of Socially Critical Research Accounts

- 2 Writing the ‘Wrongs’ of Fieldwork: Confronting Our Own Research/ Writing Dilemmas in Urban Ethnographies

- 3 Critical Incidents in Action Inquiry

- 4 Ideology and Critical Ethnography

- 5 Reciprocity in Critical Research? Some Unsettling Thoughts

- 6 The Social Commitment of the Educational Ethnographer: Notes on Fieldwork in Mexico and the Field of Work in the United States

- 7 On Writing Reflexive Realist Narratives

- 8 Journey from Exotic Horror to Bitter Wisdom: International Development and Research Efforts in Bosnia and Herzegovina

- 9 In/forming Inside Nursing: Ethical Dilemmas in Critical Research

- 10 On What Might Have Been: Some Reflections on Critical Multiculturalism

- 11 Raising Consciousness about Reflection, Validity, and Meaning

- 12 Where Was I? Or Was I?

- 13 Critical Policy Scholarship: Reflections on the Integrity of Knowledge and Research

- Notes on Contributors