![]()

Creating urban space

Andrew MacLaran

This book is about building cities. It focuses on the private-sector forces responsible for their development and the arrangements put in place to guide, manipulate and control them. Perhaps, in an era of increasing ‘globalization’, characterized by the instant transfer of finance and information across the globe, it is no longer necessary and perhaps even unwise to differentiate between urban and rural realms, at least in the developed world. Here, capitalist market-based systems, relations of production and urban-based media have penetrated the furthest recesses of the countryside, reshaping traditional ways of life, economies, politics and culture, to the extent that it becomes virtually impossible to delimit the urban arena. Nevertheless, the designation ‘urban’ does still convey meaning.

Cities are fascinating because, in our increasingly urban world, they are intimately tied into almost the complete totality of human life. This is what makes them such vibrant and exciting places in which to live and also such interesting places to study. Cities mirror the character of the society that creates and sustains them. They are therefore as multifaceted as the range of social complexity which engenders them. They express the ways in which people spend their lives, make their living and use their leisure time. They reflect the specialized forms of human economic activity which take place in urban areas, the relationships and interactions which underpin them and the legal forms which support and enforce them. They express the manner in which people are organized politically and shaped ideologically. They concern cultural, religious and artistic expression, reflecting varying forms of family life and gender roles, as well as the ways in which children are raised, educated and socialized into the adult world.

Our personal images of cities may well emphasize their social aspects, simultaneously encapsulating both positive and negative elements: the alienation of meaningless working lives, yet the almost tangible energy and stimulation of life at the economic and cultural heart of things: the congregation of people and the superficial depth of personal interactions, yet the ‘buzz’ or ‘craic’ of living to the pulse of modernism; the anonymity of the crowd, yet the behavioural freedoms this brings, unfettered by informal restraint of cleric, neighbour or even family ties; the promise of economic opportunity and social fulfilment, tarnished by realities of housing affordability crises, traffic congestion, fear of crime and for personal safety.

Obviously, then, cities are more than just buildings. Yet, a powerful and highly durable component of our image of urban areas is constituted by the built environment itself. Cities such as New York, San Francisco, Sydney, London and Paris are instantly identifiable by their unique skylines created by the massing of buildings, especially in their central business areas, or by the presence of particular landmark buildings. Even on a more intimate scale, it is hard to think of our home neighbourhoods without conjuring up an image of streets and buildings as well as the ties of family and friendships that make those places significant. Buildings themselves become endowed with personal meaning.

Cities comprise a plethora of functions, broadly relating to the productive, distributive, reproductive and exchange operations of our social system. These each have different requirements and preferences with regard to building type and urban situation. Locational competition between those functions, with their different degrees of economic power, together with the operation of planning systems which have often favoured mono-functional zoning, create an urban landscape in which different functions become inscribed in geographical space. These specialized functional areas, industrial, commercial and residential, are linked to one another through transport and communication infrastructure, facilitating the movement of goods, information and people, permitting the daily assembly of the labour force at its place of employment and its return home to recuperate after work. It is ‘built space’ which provides for the accommodation of all these activities and, if anything truly typifies the ‘urban’ and dominates our image of cities, it is probably their built environment. The chapters that follow are concerned with the making of that urban space, the product of a distinct process.

The urban fabric embodies considerable investment of materials and labour power in its construction and this can usually be written off only slowly, typically over many decades. Change is therefore normally also slow. Occasionally, whole new towns may be created but, generally, the vast majority of buildings are inherited from previous decades, sometimes from previous centuries. Nevertheless, cities do change. Buildings are adapted to accommodate different functions and land is upgraded to provide for more profitable uses. Areas whose functions have been overtaken by economic or technological change become redeveloped, while peripheral expansion accommodates growth.

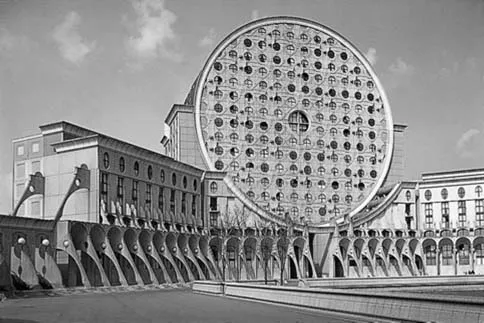

Figure 1.1 Les Arènes de Picasso, Marne-la-Vallée, France. As a non-market-related sector, social housing may exploit the freedom to be architecturally adventurous

The public sector often plays a direct role in the development of urban space, particularly of those elements which may be too risky for the private sector to undertake or which lie beyond the logic of individual capitalists to provide, such as transport infrastructure or housing for the poorer classes. However, it is normally the private sector that is responsible for the greater part of real-estate development. Therefore, it is the role of the private-sector property development ‘industry’ which forms the predominant focus of this book. The operations of this industry help to shape the built environment, influenced by powerful property interests, commercial companies and investment institutions. Indeed, as Feagin (1983, 3) has emphasized, urban space is not simply a neutral container of societal functions:

Cities under capitalism are structured and built to maximize the profits of real estate capitalists and industrial corporations, not necessarily to provide decent and livable environments for all urban residents.

However, the industry’s activities are not unfettered. The state has almost invariably sought to intervene in the process of creating the built environment through urban planning systems which seek to control, shape and influence the outcomes.

Chapters 2 and 3 provide the context for understanding the creation of the built environment. Chapter 2 describes the major agents and actors involved in the property development ‘industry’. It investigates their motivations and modes of operation, examining the relationships between them and their struggle to share in the profits which can accrue from development. It discusses the importance of location on the potential profitability of commercial property development and the impact which this can have on the urban landscape. It also reviews the existence of development cycles and their impacts on the property sector.

Chapter 3 addresses the topic of urban planning, examining its operations and briefly outlining its philosophical and ideological bases. Urban planning involves the intervention by the state, usually at local level, in the process of property development. Thus, it becomes an important influence on development by establishing the context within which the creation and redevelopment of the urban environment takes place. It may guide, support, promote or hinder development. It may regulate the way in which development takes place and seek to control its potentially adverse consequences by protecting environmental resources and conserving valued natural or built heritage. In so doing, it seeks to achieve certain desired spatial or social arrangements which otherwise may not be attained. Traditionally, intervention has involved regulating the uses to which urban land and buildings are put and controlling the character of development by determining maximum development densities (plot ratios) and building height. It may also exercise control over construction quality and vet the architectural design of schemes.

However, as urban planning comprises an activity of the state, in order to understand why the state intervenes at all in the creation and redevelopment of urban space requires some consideration of the role of the state in capitalism. Because there are several conceptions of state functions, there are necessarily several distinct interpretations of the role of urban planning and these require brief review.

The chapter draws particular attention to the manner in which strategic urban planning goals and the practice of urban planning have tended to change in recent years. As the operations of the state itself have tended internationally to become more ‘entrepreneurial’ and facilitative of the interests of capital, so changes in urban governance have frequently led to the transformation of urban planning towards more directly proactive modes of operation supportive of private-sector development interests. Consequently, urban planning has encompassed property-led urban regeneration policies promoted and often generously supported financially by the state, as it has attempted to harness the forces of property development in strategies of urban growth and renewal, thereby enhancing and transforming the city’s image and boosting urban competitiveness for inward investment. Thus, the conception of urban planning as an obstructive hurdle to development has become largely displaced in the western world over the past 20 years as it adopted increasingly entrepreneurial approaches that provided selective inducements to tempt developers towards certain courses of action rather than others. Increasingly, the carrot has tended to replace the stick.

The broad introductory discussions of Chapters 2 and 3 create a framework for understanding the nature of property development and the functions of urban planning. However, unique national and geographical situations arise which influence the precise outcomes. It is these twin elements of planning and development which are taken up in the six case-study chapters that follow (Chapters 4–9), adding flesh to the skeleton of generalization provided by the earlier chapters. Six cities have been selected for inclusion. Two are North American, two Australasian and two North European. They are Minneapolis (Minnesota), Sioux Fall (South Dakota), Sydney (New South Wales), Auckland (Aotearoa/New Zealand), Birmingham (England) and Dublin (Ireland). They share a certain heritage with respect to planning practice and a similar ethos concerning private property rights.

The selected cities are not of first rank on the global stage. There are two main reasons for this choice. First, world cities such as London and New York are unusual in many respects, being more closely tied into global events and processes compared to those of secondary or tertiary status which have more intimate regional ties. Their stock of buildings tends to reflect this. For example, London’s huge stock of office property comprises around 60 per cent of the UK total. The interest of property developers and investors also tends to be drawn from a global scale. Second, both New York and London have already been the focus of some excellent and readily available reviews, notably that of Fainstein (1994).

The aim of these case-study chapters is to investigate the ways in which urban planning in different national contexts has sought to influence the results of the property development process and the way in which the modes of operation of planning have developed in order better to effect such influence. This strategy argued strongly in favour of cities which were more typical of their societies, where the roles of the regional economy and local planning systems were more evident, yet which were still of a sufficient scale to experience significant property development pressures.

The first of the case studies is based on Minneapolis, Minnesota. Its focus is somewhat different from the remaining five cities as the chapter sets out to demonstrate, in the context of a market-dominated economy, that urban planning historically was a creature of private-sector needs. It aims to contradict the notion that planning represents some radical challenge to private property rights or a conspiracy to thwart the interests of the development sector. It shows instead that urban planning was in fact conceived in response to the requirements of downtown property and business interests and that it engaged from its earliest days in a highly entrepreneurial role which facilitated those interests. This conferred immense benefits on those with property, while imposing enormous real costs on those without.

The second of the case-study chapters focuses on Sydney, New South Wales, as it endeavoured to establish itself as a business centre of global significance. In examining the transformation of its central business area, the chapter addresses the problems which result from the fragmentation of urban planning authority between regional and local levels of control. With a predominantly state-level planning authority which was highly supportive of the property development sector, it reveals the difficulties that locally-based planning experienced in balancing the demands of developers with the conflicting views and objectives of community groups about the manner in which the central area was to develop.

Dublin, Ireland, is the subject of the third case study. It reviews how traditional urban planning, based on land-use zoning and development control, proved largely ineffective in dealing with the intensity of inner-city decline and dereliction prevailing during the 1980s. It examines the national government’s response to such shortcomings, notably the creation of financial incentives for designated urban renewal areas and the establishment of special-purpose agencies to promote private-sector property-based renewal. This engendered a marginalization of traditional urban planning and led to a rethinking of the operations of urban planning in the city.

The changing dynamics between the various agents involved in urban development are investigated in the study of Auckland, New Zealand. It examines the transformation of the city’s central business area during the course of a major office development boom, the subsequent boom in the construction of high-rise apartments and, finally, the impact of partnerships between the public and private sectors in the creation of ‘spaces of consumption and spectacle’.

The chapter on Birmingham, England’s second city, examines the way in which national planning policy has been interpreted locally. It reviews the manner in which the city has sought, by taking cognisance of the needs of property developers and investors, to employ the transformational power of the private-sector property development industry to recreate itself as a city of the twenty-first century.

The final case study reviews the transformation of Sioux Falls, South Dakota. It takes up the theme of urban ‘boosterism’ and examines the way in which the forces of property development have been harnessed locally in a strategic project to transform the city from a provincial north-plains meat-packer to a financial business centre of national significance. It shows how planning and property development have been used by the business élite in a scheme to re-create the urban landscape as one which embodies the culture of economic expansion, in which the urban landscape itself has become transformed into an icon of growth. However, as the authors are at pains to show, in this process of reshaping the city, clear winners and losers have inevitably emerged.

It should become apparent that, despite their geographical distance from one another, there is considerable similarity between the case studies in terms of the problems experienced, the planning processes adopted and the resultant outcomes.

![]()

Masters of space: the property development sector

Andrew MacLaran

This chapter reviews the operations of the property development sector, the industry largely responsible for making and re-shaping the built form of our cities. It focuses on private-sector operations, investigating the roles of the major actors and agents involved in the process of development, their motivations and the relationships between them. It examines the industry’s propensity to undergo cycles of boom and slump in the scale of development activity and reviews some of...