![]()

1

Start Here

1.1 Challenges

At a time when we are divided both collectively and individually by walls, this book seeks to build bridges, to cross boundaries and establish connections. Collectively, we have built a wall between science and spirituality that cripples our imagination. Today the interrelated resurgences of populist nationalism and religious fundamentalism are building walls, sometimes literally, between nations, races and creeds. Neoliberal policies steered by corporate agendas have reinforced the pre-existing walls between rich and poor, and erected new ones to protect political and commercial oligarchies. Individually, we have built walls that isolate our ego from both inner and outer nature, by which I mean from our inner being or soul and from the outer, other-than-human world respectively. The walls that shelter us from the truth and from those who think differently are being massively reinforced by modern communications technologies and media, especially the internet. We have walled off our knowledge into academic disciplines, each with its own theories, models and terminology. In short, our entire mode of mental functioning is fragmented to the point of incapacity at a critical juncture in human history when, as an absolute minimum, what British civil servants have liked to call ‘joined-up thinking’ is required.

This book bucks the trend by identifying and exploring some remarkable correlations between disciplines, each of which is intrinsically holistic. Thus ‘Gaia’ in its title refers to the Gaia hypothesis, now theory, formulated by James Lovelock and Lynn Margulis; ‘Psyche’ indicates the depth psychology originally developed by Carl Gustav (C.G.) Jung that is widely known as ‘analytical psychology’; and ‘Deep Ecology’ is a philosophical and practical worldview that values all life equally, propounded by the Norwegian philosopher Arne Næss and others. The aim of this synthesis is to prepare us for the Anthropocene Epoch in which the great forces of nature are becoming irreversibly more unpredictable and hostile to life itself because of human activity, a challenge which should not be underestimated. For example, consider the dilemma posed by the following two contemporary statements, both of which are essentially as true as they are unwelcome:

Ours is the first generation to properly understand the damage we have been doing to our planetary household, and probably the last generation with a chance to do something transformative about it.

(Raworth, 2017: 286)

The green movement, which seemed to be carrying all before it in the early 1990s, has plunged into full-on mid-life crisis. Unable to significantly change either the system or the behaviour of the public, assailed by a rising movement of ‘sceptics’ and by public boredom with being hectored about carbon and consumption, colonised by a new breed of corporate spivs for whom ‘sustainability’ is just another opportunity for selling things, the greens are seeing a nasty realisation dawn: despite all their work, their passion, their commitment and the fact that most of what they have been saying has been broadly right—they are losing. There is no likelihood of the world going their way. In most green circles, sooner or later, the conversation comes round to the same question: what the hell do we do next?

(Kingsnorth, 2013/2017: 131)

Kate Raworth, who has recently rethought economics from the ground up (she describes herself as a ‘renegade economist’), succinctly explains why we have to act now. However, my own environmental engagement, which has ranged over decades from direct action to technical consulting to governmental lobbying to lecturing and writing, bears out self-confessed ‘recovering environmentalist’ Paul Kingsnorth’s bleak assessment, unpalatable as it is. Many other thinkers and writers implicitly or explicitly endorse either or both of these statements. What emerges from these two examples and my own experience is acknowledgement that the route we take next will have to be radically different from our present road to hell that is only partially paved, at best, with good intentions. This book points to an entirely different path. It won’t be easy; hence it’s tempting to just ignore the whole problem. In the preface to his highly recommended Defiant Earth: The Fate of Humans in the Anthropocene, Professor of Public Ethics Clive Hamilton characterises our response to the Anthropocene as the ‘great silence’ and recounts:

At a dinner party one of Europe’s most eminent psychoanalysts held forth on every topic but fell mute when climate change was raised. He had nothing to say. For most of the intelligentsia, it is as if the projections of Earth scientists are so preposterous that they can safely be ignored. Perhaps the intellectual surrender is so complete because the forces that we hoped would make the world a more civilised place—personal freedoms, democracy, material advance, technological power—are in truth paving the way to its destruction. The powers we most trusted have betrayed us; that which we believed would save us now threatens to devour us. For some the tension is resolved by rejecting the evidence, which is to say, by discarding the Enlightenment. For others, the response is to denigrate calls to heed the danger as a loss of faith in humanity, as if anguish for the Earth were a romantic illusion or superstitious regression. Yet the Earth scientists continue to haunt us, following us around like wailing apparitions while we hurry on with our lives, turning around occasionally with irritation to hold up the crucifix of Progress.

(Hamilton, 2017: x–xi)

To face up to the challenges of the Anthropocene proportionately and honestly isn’t just a social taboo, it is political and, so we are told, commercial suicide. It is nonetheless my contention, as one of Europe’s less eminent psychoanalysts, that the realisation that we are now living in the Anthropocene demands nothing less than a metanoia—a revolution in the way we understand our being in the world. The unprecedented magnitude, suddenness and longevity of our impacts on Earth’s atmosphere, oceans and land have already begun to have grave environmental and humanitarian consequences. These include, respectively, geophysical degradation and the sixth mass extinction, most notably through climate change (global heating),1 pollution and depletion, and geopolitical destabilisation, for example forced migration and resource conflicts. While we know that the behaviours of such massively interconnected systems as Earth and human society means that the consequences will take decades or longer to unfold, these systems’ inherent complexity and nonlinearity renders the timing and severity of their responses dangerously unpredictable. By the time we know for sure what to expect, if that ever comes, it will be too late; the imperative to apply the ‘precautionary principle’ is therefore axiomatic. As historians Christophe Bonneuil and Jean-Baptiste Fressoz warn in The Shock of the Anthropocene, to frame the Anthropocene as just another crisis is gravely mistaken because

does it not maintain a deceptive optimism? It leads us to believe, in fact, that we are simply faced with a perilous turning-point of modernity, a brief trial with an imminent outcome, or even an opportunity. The term ‘crisis’ denotes a transitory state, while the Anthropocene is the point of no return. It indicates a geological bifurcation with no foreseeable return to the normality of the Holocene.

(Bonneuil & Fressoz, 2017: 21)

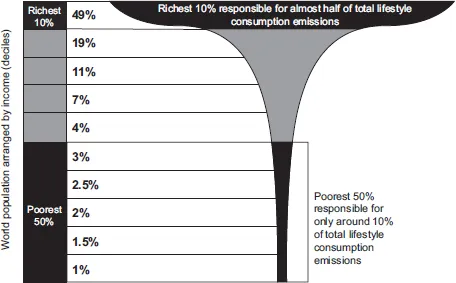

However, despite being both sole agents and among the victims of the Anthropocene, our actions to date have been demonstrably inadequate. This is a disgraceful failure, since we have both the science to understand and the means to meet Raworth’s challenge. So why, when we know what to do, have we chosen not to do it? There is of course no single or simple answer, but it is surely in part because the principal agents and human victims are mostly not the same people. By far the highest per capita planetary impacts result from the lifestyles of the affluent; but the human suffering their aggregated consequences cause is borne primarily by the poor in the majority world, conveniently far away and out of sight. A quantified example of this is shown in Figure 1.1, which illustrates the disparity of agency for emissions of CO2—the principal anthropogenic driver of climate change and ocean acidification.

FIGURE 1.1 Percentages of CO2 emissions by world population. (Gore, 2015: 4)

This shows emissions resulting from direct consumption by households only, which globally is about 64% of the total, though this varies by country. Emissions associated with consumption by governments, capital and international transport sectors of the economy are excluded. Further explanation of the underlying calculations and assumptions is freely available in an Oxfam technical note (King, 2015). Gore notes that:

the poorest half of the global population—around 3.5 billion people—are responsible for only around 10% of total global emissions attributed to individual consumption, yet live overwhelmingly in the countries most vulnerable to climate change. Around 50% of these emissions meanwhile can be attributed to the richest 10% of people around the world, who have average carbon footprints 11 times as high as the poorest half of the population, and 60 times as high as the poorest 10%. The average footprint of the richest 1% of people globally could be 175 times that of the poorest 10%.

(Gore, 2015: 1)

Unsurprisingly, most of the world’s 10% highest per capita emitters still live in Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries, and around a third are from the U.S., which means that we are probably among them. This has led some to object to the term ‘Anthropocene’ because it implies that all of humanity is equally to blame. I agree with this objection; but in lieu of a better and as widely known alternative I will continue to use the term ‘Anthropocene’ with the caveat that just because it is solely attributable to human activity does not mean that all humans are equally responsible. Ever was the disparity of human privilege and blight thus, at least since the Industrial Revolution as, for example, the settlement patterns of major cities and siting of known pollution sources reveal. Such iniquity is now on a global scale, and so the demand for environmental justice is, quite rightly, gaining traction. However, this is vastly more than a human-only issue. Other-than-human life is also suffering, but is likewise largely shut out from our consideration by the psychological and physical walls that we have built between ourselves and the natural world. The root cause of the problem isn’t economic, political, institutional, legal or technological, or any combination of these alone—even though these sectors can and should all contribute to its solution. To respond adequately to the challenges of the Anthropocene, we must first acknowledge some even more ubiquitous and intractable ‘inconvenient truths’.

Firstly, the laws of ‘outer’ nature, of the physical world, do not bend to human will; nor do they conveniently desist when ignored. Failure to accept these incontrovertible facts is simply delusional; denying the former is symptomatic of hubris, the latter of inertia, nostalgia, evasion or, more seriously, Machiavellianism. The extent and hardening of such denial, and the associated character traits—particularly among those with the greatest power, influence and ecological footprints—endangers everyone, above all those at the opposite end of the wealth spectrum who are disenfranchised by poverty. Of course, we have manipulated the physical world throughout our history to develop the technology on which our civilisation increasingly depends; but we have done so by discovering, understanding (albeit still incompletely) and exploiting the laws of nature. Changing or disregarding them has never been, and never can be, an option.

Secondly, the laws of ‘inner’ human nature, of our psychological world, inevitably include human will, but extend far beyond it. Disregard does not stop them any more than it does physical laws, but is in itself an exacerbating factor with unpredictable and hazardous consequences. Despite, or arguably because of, the European ‘Enlightenment’, we remain at the mercy of often archaic unconscious forces, including our animal instincts; we are not as exclusively modern or rational as we like to think. Failure to accept these humbling realities is no less deluded yet, astonishingly, goes absolutely unchallenged in mainstream society. Unfortunately our discovery, investigation and understanding of such psychodynamics are often academically marginalised by incompatibility with the established, but now questionable, criteria of ‘objective’ Western science. More to the point, they are unwanted distractions from ‘business as usual’. After all, what good did self-knowledge ever do for the economy?

It is therefore hardly surprising that we seem to understand the world of matter much better than we do the world of mind. This was memorably summarised (and attributed to Albert Einstein) on a placard I saw at a demonstration against nuclear weapons in the seventies: ‘Technologically we are in the Atomic Age. Psychologically we are in the Stone Age.’ Exaggeration certainly, and false attribution perhaps; but few would wholly disagree with the underlying premise, which has certainly been confirmed in my professional experience. Many years of political, institutional and corporate negotiations during my former career in the energy sector have shown me that reason and realism rarely, if ever, prevail. For example, so-called ‘free market’ economics, that Holy Grail of neoliberalism, are anything but, thanks to massive institutional subsidies and almost universal failure to internalise or even quantify external costs; the ‘information deficit’ model—the belief that providing sufficient objective information promotes rational decision-making—repeatedly fails, so some prejudices enshrined in policies can withstand any amount of contradictory evidence; and across the outmoded left–right political spectrum we perpetuate a state of cognitive dissonance by demanding both economic growth and ecological sustainability. Self-interest dressed up as ideology which, in turn, masquerades as reason is the well-disguised elephant in the boardroom; dispassionate and compassionate common sense must wait outside.

Our tunnel vision, increasingly walled in by deliberate disinformation and algorithm-driven confirmation bias, is ephemeral and parochial, i.e., it is fragmented in time and space respectively, and thus totally unsuited to tackling the challenges posed by the Anthropocene that are, in contrast, inherently long term and delocalised. We desperately need a wider alternative worldview that is plausible, intelligible and appropriate. As a minimum, this means it has to be coherent, substantive, transnational and translatable into effective practice in our personal and, where possible, working lives. Taking all these criteria and more into account, I will propose an original approach to this metanoia that the current predicament of humankind and the planet demands.

Ecopsychology, the origins of which can be traced back to the early nineties, deserves special mention at this point. Definitions and descriptions of it abound in print and on the internet. For example, according to the International Community of Ecopsychology (2017),

Ecopsychology is situated at the intersection of a number of fields of inquiry, including psychology, ecology, spirituality, and environmental philosophy, but is not limited by any disciplinary boundaries. Put most simply, Ecopsychology explores the synergistic relation between personal health and well-being and the health and well-being of our home, the Earth.

Two aspects of this statement are noteworthy. Firstly, it resonates with the trans-disciplinary nature of this book. Secondly, its non-hierarchical formulation of the person–planet relationship suggests a spectrum of endeavour from deep ecology, where this book is situated, to ‘ecotherapy’, in which nature is used to promote human psychological well-being. The majority of peo...