![]()

p.1

1

STEPPING UP FOR LGBTQ AND GENDER DIVERSE STUDENTS

Schools in the United States continue to be antagonistic environments for students who embody and express sexual and gender identities beyond what Atkinson and DePalma (2009) call heterosexual hegemony. This is well and regularly documented by the Gay, Lesbian, Straight Education Network’s (GLSEN) biannual nation-wide school climate survey of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) students. Even the most recent of these reports show that where LGBTQ youth persistently experience biased remarks, victimization, harassment, and assault, they exhibit pervasive absenteeism, lowered educational aspirations and academic achievement, and poor psychological well-being (Kosciw, Greytak, Giga, Villenas, & Danischewski, 2016). However, when teachers and other adults offer social support, protection from victimization, and active advocacy for LGBTQ youth in schools, including sponsoring or supporting the presence of Gay–Straight Alliances, developing and delivering inclusive curriculum, and providing comprehensive bullying and harassment policies that include enumerated language, these students’ sense of school belonging, academic success, and overall psychological well-being are enhanced (Kosciw et al., 2016; Murdock & Bolch, 2005).

Unfortunately, though, GLSEN data also show us that, according to the students who responded to their most recent survey, only 36.5% of students who are harassed or assaulted because of their perceived sexual identities or gender expressions report these incidents to school staff. When they do report harassment or assault, 63.5% of the time, school staff, including but not limited to teachers, do nothing or, at most, tell students to ignore the behavior (Kosciw et al., 2016). To make matters even worse, school personnel actually contribute to such remarks. Over half (56.2%) of those surveyed reported “hearing homophobic remarks from their teachers or other school staff” (Kosciw et al., 2016, p. xvii) and even more (63.5%) heard teachers or other staff make “negative remarks about gender expression” (Kosciw et al., 2016, p. xvii). We1 repeat, not only are educators failing to interrupt homophobia and transphobia with any frequency, they are even contributing to the hostility LGBTQ students experience at schools with their own comments. This reality, and our combined frustration and curiosity about why any teacher or other adult in a school would fail to interrupt homophobia and transphobia, and even worse would contribute to it, was the impetus for this book.

p.2

As teachers ourselves, we argue that it is our responsibility to step up for LGBTQ and gender diverse students. And, as educational researchers, we claim that it is the job of teacher educators to provide guidance, support, and information for doing this work. We know that this work can be daunting and feel impossible. But we also know that it can be done, in part, because we’ve done it. Here, we aim to show that by working with students, through and beyond curriculum, as well as by working with families and administrators, any teacher, whether novice or experienced, elementary or secondary, can improve school culture for LGBTQ and gender diverse students. We understand this work to require information and courage rather than expertise. It can take the form of big acts but also everyday small acts. We also believe that there is no “right way” to take action. Instead, these acts of advocacy must be multiple, variable, flexible, and organic. It is through this work and these acts that teachers will make schools better places for LGBTQ and gender diverse people.

In this chapter, in particular, we introduce you to our teacher inquiry group, the Pink TIGers, by sharing a brief history of our group and the commitments and questions that drive our work. We then go into detail about the project, including some of its limitations, and delineate the theories that undergird the project that this book represents. Finally, we prepare you, as readers, for the rest of the book, by introducing you to the school contexts featured most prominently and laying out the organizational structure of the book.

First, though, we comment a bit on our use of terminology. We often use LGBTQ. We do not mean to exclude any people who may not see themselves in this acronym, but we also hope to represent accurately the people who shared their stories in this project. For us, LGBTQ means lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, and queer. We use trans to capture the broad diversity of non-cisgender people who make up trans communities, and we use Q for queer to reflect people who experience their sexual and gender identities fluidly and/or prefer for these identities to remain suspended. On a related note, you will see that we use both Queer and queer. We use Queer with more precision, drawing on Queer Theory, that is to mean the disruption of norms in relation to sexuality and gender. We use queer, though, as an umbrella term, much like LGBTQ, but with more fluidity, variability, multiplicity, and even ambiguity (and a lot fewer syllables). We do not include asexual or intersex, as examples, because these were not identities that played a prominent role in our work. To include them, therefore, would be dishonest. Sometimes, though, you will notice we use a variation of the LGBTQ acronym. Typically, this is because we are respecting someone else’s choice, so, for example, GLSEN uses LGBT not LGBTQ in reports published before 2016. We therefore use LGBT when referencing these earlier reports. You will further note that we also include “gender diverse” (Nealy, 2017) in the list of gender expressions. This is a term that describes people who experience gender outside of the heterosexual matrix (Butler, 1990) but who have not, necessarily, claimed (or rejected) any particular sexual or gender identity. Our intention is to be as inclusive as possible without being dishonest.

p.3

The Pink TIGers

We know about the experiences of LGBTQ and gender diverse youth in U.S. schools not only from the GLSEN reports, but also from our own experiences in schools. We are all part of a group we call the Pink TIGers, pink for the pink triangle claimed as a symbol by many LGBTQ people, and TIGers as an acronym for our Teacher Inquiry Group and an indication of our aspired ferocity in fighting for equity and diversity. The Pink TIGers began meeting in 2004 with a commitment to interrogating heterosexism and homophobia in Central Ohio, with a belief that teacher professional learning could and should go beyond one-time, one-day, top-down professional development sessions in schools. By 2009 we were actively attending to transphobia as well. Fueled by these commitments and beliefs, the Pink TIGers, as an inquiry group, have been continually meeting and learning together for over 12 years. Three of the original members are still participating. And four members, who each contributed to our first Pink TIGer book Acting Out! (Blackburn, Clark, Kenney, & Smith, 2010), remain active group members. Others have moved away, or moved on to other phases of their teaching lives, with many new members joining; but to a person, we all remain committed to contesting heterosexual hegemony in schools and communities. The Pink TIGers, then, reflect the kind of sustained and sustaining professional learning and real change that we believe can occur when teachers work together, over time, around shared questions and commitments. With this history as a backdrop, we introduce you to the current group of Pink TIGers who wrote this book.

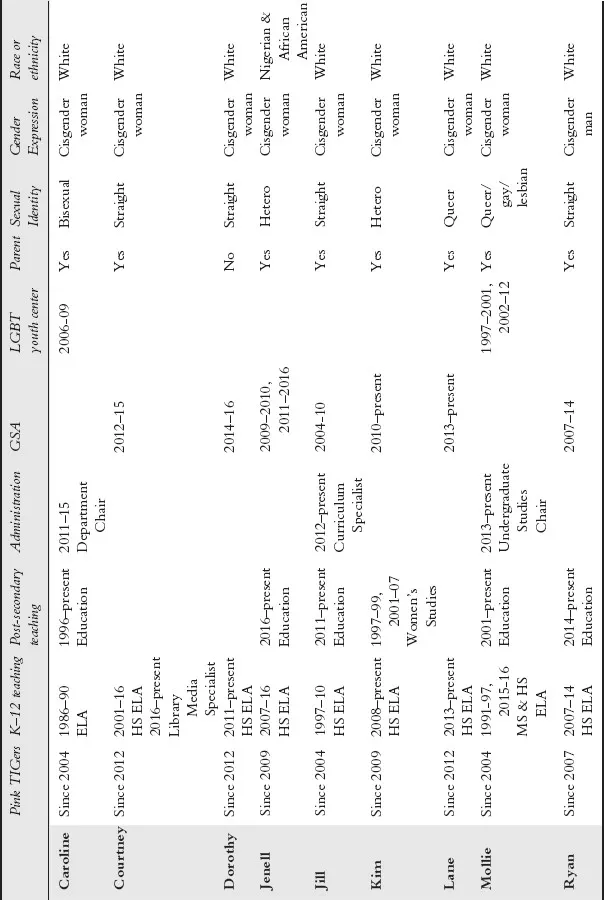

All of us have been teachers, and most of us still are. Our K-12 teaching experience has been predominantly in high school English language arts. One of us shifted from being a high school teacher to being a Library Media Specialist. Additionally, six of us have university teaching experience, mostly in education but also in women’s studies. Some of us have held or continue to hold administrative positions, at both K-12 and post-secondary institutions, that have challenged us to consider how superintendents, and principals, among others, shape the climate and culture of a school and affect the lives of LGBTQ and gender diverse students. All of us have been students, and some of us still are, but now in graduate school. Although none of us were out as anything other than straight and cisgender when we were in K-12 schools, we have extensive experience working with those who are. Six of us have led, or still lead, our school’s Gay Straight Alliances or Genders and Sexualities Alliances (GSAs).2 Two of us volunteered at one or two LGBTQ youth centers. Many of us were parents, although only two of us were parenting children in schools with same-gender partners. In other words, we brought a vast range of experiences to the topics we explore in this book.

p.4

We have been in conversation with one another as well as additional Pink TIGers about the topics in this book since 2014. Three of us have been a part of the Pink TIGers in monthly meetings since its inception in 2004; one of us joined three years later, in 2007; two of us joined two years later, in 2009; two more in 2012 and one more in 2013. And these counts don’t even include the Pink TIGers who elected not to participate in this book project, all of whom informed our work together. That is to say, we have been talking about the content in this book for a long time. From 2004–2014, we audiotaped all of our meetings. From time to time, we shared individual written reflections on these meetings and our experiences in this group. These materials add to the richness of what we have learned about working with LGBTQ and gender diverse students through our interactions with one another.

These conversations have been driven by the belief that, as Jill3 said, “LGBTQ students deserve the best we’ve got, and we’re simply not there yet.” Together we, in Courtney’s words, “inspire and challenge one another to be better allies.” And, as Kim notes, we “enrich our own practice by sharing with others.” We do this by bringing to the group what we are struggling with in our lives and, mostly but not entirely, in schools. For example, Jenell brought to the group the “challenges trans students have faced” in the schools at which she worked, which, in turn, brought to light the dearth of resources and the lack of preparation that educators have available to support trans students. Jill talked about how

And through their work and stories of co-advising their school’s GSA, Jenell and Courtney helped us to see the importance of these groups in schools, as well as their limitations. As Jenell puts it, a “GSA can support students socially and emotionally, and function as an extended family for kids . . . . GSA work has helped us shape students into advocates for themselves and agents of change.” But, as Courtney notes, despite being these positive places for some students, we need to keep in mind that “GSA may not be a space where all queer kids feel safe and secure.” Together, as Kim points out, we have come to understand the need to “embrace mistake-making as opportunities for growth and compassion.” Our talking, writing, and reflecting together at meetings shapes how we now act in other places and spaces. As Courtney states, “When a queer kid needs a well-informed ally, I now ask myself, ‘What would a Pink TIGer do?’” Our hope is that this book provokes you, as readers, to ask and prepares you to answer this same question.

p.5

Table 1.1 The Pink Tigers

p.6

That said, when we use the term “ally,” we do so with some ambivalence. We wonder whether someone gets to claim that identity or whether it gets awarded, and if the latter, by whom. We also think that no one is always an ally. It is not a stagnant identity. One might always strive to be an ally, and sometimes achieve this goal and other times not. We appreciate the work of Schniedewind and Cathers (2003) on this point, whose work documents how people can be taught about and learn to be allies; that we are all always learning to do this in our lives, even when we mess up; and that being an ally can be hard. As they note, an ally is “someone who didn’t have to be there, but they chose to act . . . they stand up for those being targeted because of any ‘ism’” (pp. 188–189). Whether we use ally or advocate or something else, our challenge is the same, to choose to act.

While our work on Acting Out! made us keenly aware of the damage that homophobia and heterosexism can do, especially to young people in schools, we became concerned about potentially reinforcing rigid, heteronormative boundaries by focusing strictly on homophobia without attending to disrupting binaries related to sex and gender identities. Through sharing our stories and experiences as educators, we knew that gender binaries were being policed and reinforced beginning in pre-school and continuing on into K-12 and university classrooms.

Between 2009 and 2010, in the midst of our reading and learning about gender binaries and the impacts of heteronormativity, several young people across the U.S. committed suicide for either being gay or being perceived as gay. The quick succession of these suicides caught the attention of the media and shined a bright light on the issue of LGBTQ youth suicides and bullying. These events also prompted the gay columnist Dan Savage and his partner, Terry Miller, to start the “It Gets Better” project, a web-based collection of videos from celebrities and politicians to everyday adults and young people, aimed at communicating to LGBT youth, worldwide, that life gets better and is worth sticking around for, regardless of how terrible it may feel in the moment.

Even as we were shattered by each of these deaths, we noticed, too, that as the focus turned to bullying more generally, attention to homophobia, heterosexism, and LGBTQ students was dropped, creating a comfortable place for policy makers, legislators, and educators to stand against bullying without standing up for LGBTQ and gender diverse people. Witnessing these events and this turn toward bullying and away from its contextual causes surfaced new questions for inquiry and expanded the focus of our group. Together, we wondered why seemingly less powerful people, like early career teachers or students themselves, would go to extraordinary lengths to support LGBTQ and gender diverse students in schools while seemingly powerful people, like administrators, policy makers, or more experienced educators, would not. These wonderings propelled the project that is the focus of this book.

p.7

With respect to the project this book represents in particular, we were driven by our questions about why people in and around schools sometimes step up, and other times do not, as or on behalf of LGBTQ and gender diverse students. Why would teachers fail to intervene when a homophobic or negative comment about gender expression was said in their presence? Why on earth would they make such a comment themselves? These questions evolved into our research questions:

• What do teachers, students, their families, administrators, and other school personnel say about their experiences with advocacy for LGBTQ and gender diverse people in schools?

• In the stories they tell, when, where, how, and under what conditions do they understand themselves as experiencing support as LGBTQ and gender diverse people and/or supporting LGBTQ and gender diverse people in schools or not?

To answer these, we wanted more perspectives than our own, maybe people who were a little more ambivalent about how to navigate tensions created by homophobia and transphobia. We were used to gathering one another’s stories in our monthly meetings, but we wanted the stories of other teachers who were not, necessarily, interested in making a long-term commitment to a teacher-inquiry group. Plus, we wanted stories of people besides teachers, such as students, parents, and administrators, and their participation in our teacher inquiry group would not even make sense. We wanted the stories of the students and parents with whom we shared friendships and the stories of teachers and administrators with whom we worked. We wanted to know more about these people and their work to inform our own but also to inform the work more broadly speaking. That is, we wanted to know their stories to inform how all stakeholders might work together to interrupt homophobia, heteronormativity, transphobia, and cisnormativity in classrooms and schools.

The Project

So, knowing the challenges LGBTQ and gender diverse youth experience in schools and striving to engage in humanizing research with the goal of making schools better for these young people, we engaged in a study different than any we had ever done before. Instead of inquiring into our own individual classrooms, as teacher researchers, and exploring how we might improve the lives of LGBTQ and gender diverse students through our curricula and pedagogy, as we did in our earlier book, this time we turned outward. We turned to students and parents, teachers and administrators, as well as other school personnel. We asked how they advocate for LGBTQ and gender diverse people in schools. We asked them when, where, how, and under what conditions they understand themselves as stepping up on behalf of LGBTQ and gender diverse people or not. We asked them, and, in our...