![]()

Part I

Contextual investigations

True opinions are a fine thing and do all sorts of good so long as they stay in their place; but they will not stay long. They run away from a man’s mind, so they are not worth much until you tether them by working out the reason. . . . Once they are tied down, they become knowledge, and are stable. That is why knowledge is something more valuable than right opinion. What distinguishes one from the other is the tether

Socrates (Plato, Meno)

![]()

1 War

There is an increasing call for holistic approaches to problems. This chapter discusses some contemporary examples of this call in order to highlight some key points of the holistic approach which are rarely, if ever, mentioned or understood. It concludes by arguing for a distinctly epistemological investigation if the idea of a holistic approach is ever to materialize as a practical alternative to problem resolution.

1.1 The holistic/systemic approach

The holistic approach is gaining support in tackling problems. It is called upon when the treatment of a problem through the isolation of its constituent parts is rejected. This rejection usually criticizes such treatment not only as reductionist but also as too involved in the short term so that the longer term goals or consequences are detrimentally ignored. In an interview given by the then leader of the UK Liberal Democrats, Charles Kennedy, to the BBC’s Peter Sissons on 4 June 2001, Kennedy calls for a holistic approach in exactly this sense:

Now these things can’t all be isolated one from the other. I think it’s part of the holistic approach to government which is longer-term and I think more far-seeing than the short-term which has tended to plague successive British administrations.1

In this, not only is there expressed a straightforward need for a holistic approach to problems, but it is assumed as obvious that the holistic approach offers broad methodological guidelines – themselves implying underlying epistemological guidelines – for dealing with the longer term future, for coming to know it, in a holistic manner.

The holistic approach ranges from a simple inclusion of as much relevant and related data to a problem as possible, to the formation of interdisciplinary groups with the specific task of tackling a particular problem holistically, that is, by incorporating each group participant’s input to the situation. A good example of the former, including its illustration of how easily what is deemed relevant and related data can increase exponentially, is given by Churchman (1979) in his discussion of the classic approach to inventory management. A good example of the latter is the formation of a think-tank charged with finding a ‘holistic’ way of improving UK flood defences to prevent a repeat of the 2000/2001 damaging floods which swept the UK.2 Chaired by the Chartered Institution of Water and Environmental Management, it includes water engineers, house builders, insurers, the Environment Agency and flood victims. Across such a range of application, the holistic approach demands a process of ‘sweeping in’ – to borrow a term from Churchman (Ulrich, 1988a) – as much related and relevant variety as is manageably possible.

It is notable that the discussion has already referred to one of the leading thinkers in the history of the field known as system theory – C.W. Churchman – and to one of his most remembered concepts, the concept of ‘sweeping in’. Indeed, there can be no talk of a holistic approach without referring to system theory, for it is this field of thought which has championed the idea of a holistic approach to problems. Given this, any attempt at understanding the holistic approach is necessarily an attempt at understanding system theory, indeed is the attempt to understand system theory.

Where holism reigns, therefore, the notion of system follows. Hardly a month goes by without a situation being said to exhibit systemic characteristics. The Inquiry into the 1997 Southall rail disaster in the United Kingdom, for example, found that

it would be wrong to concentrate on the failings of the driver when there is compelling evidence of serious systemic failings within Great Western [Trains].3

Following the killing of an African-American youth by a police officer in Cincinnati, Ohio in May 2001, the head of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People said that he believed:

the problems in [the police] department are systemic and they span the last two decades.4

In the autumn of 2000, the Hungarian newspaper Nepszava reported its concern over the methods of the country’s right-wing government by writing:

The unrestrained and vulgar hatred-speeches against political rivals now common in parliament … degrade and threaten the peaceful systemic change based on social consensus.5

Setting up an alert on the Google News Internet site for the keyword systemic yields, on average, three to four alerts per week.6 Addressing systemicity is obviously currently fashionable. In the introductory words of the pioneering system theorist, Ludwig von Bertalanffy7 (1968: 3):

if someone were to analyse current notions and fashionable catchwords, he would find ‘systems’ high on the list.

Such a statement probably rings more true today than in the 1960s when it was first written. Though it might ring more true, however, the notion of system, or holism, is more difficult to grasp than, say, the deterministic, reductionist approach. One reason may be the manner in which the idea of system renders difficult, or even constrains, the identification of causes of effects. In the above examples, this translates into the apportionment of blame.

1.2 Blame dynamics

Seven people die and more than a hundred are injured in a train disaster. Emotions run high. Someone must take the blame: the train driver, the signals operator, the rail track company, the train company, the government – anybody, but somebody must take the blame to quench the anger and the suffering. The Inquiry, however, concludes that there is no straightforward guilt, only systemic failings within the train company. What does this mean? Where can the finger be pointed so that the anger is appeased?

An African-American youth is killed by a white police officer in the United States. The officer receives what some perceive as ‘a slap on the wrist’. The penalty is not severe enough. Blame has not been given its due. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, moreover, the very association to which African-American youth might look for some action in apportioning blame, concludes that the problems in the police department are systemic. How does systemicity help apportion blame? How has this wrong been righted by reverting to systemicity?

The Hungarian newspaper Nepszava makes systemic change proportional to, and a function of, consensus. How exactly can this relationship between systemicity and consensus be described, and how would that help to resolve situations which exhibit systemic characteristics? How can consensus be found in situations steeped in conflict?

Appeals to systemicity in such contexts appear irrelevant and perhaps even insulting to the ears of those affected, of those who (believe they) know that, at bottom, someone must take the blame. Blame is a serious issue in such examples. It is not just some short term solution to the respective problem, for if there is a wrong then the source of this wrong must be discoverable – in much the same way as, if in general terms there is an effect, then the source of this effect, the cause, must be discoverable.

The line between blame and scapegoat tactics, however, is very thin. At worst, the blame approach risks throwing society back to the middle ages where a crowd mentality creates the superficial division between innocent spectators and executed guilty, enabling society to wash its hands of the committed evil once the blame has been apportioned. The very notion of consensus, stressed by Nepszava, opposes this division and makes it difficult for anyone to wash their hands of the situation. Consensus implies togetherness, indivisibility. Most of all it implies joint responsibility so that, if there is a wrong, all parties have contributed to this wrong. Consensus does not allow anger and suffering to be quenched at a stroke; it offers only more calls for understanding, more exploration of the situation. Consensus politics is much more demanding on the heart and mind than blame politics. It is also much more fruitful. For the application of systemicity to a situation gives rise to the possibility of redesigning the situation, contrary to solely apportioning blame whilst leaving the situation unchanged. There is a very real possibility, in other words, that the situation itself has enabled the problem to arise, and that the fact that someone has done wrong has been enabled more by the situation than by any other factor. The wrong might very well be a secondary product of the primary reason for its occurrence: the situation itself. In effect, blame takes a back seat in systemic problem resolution – if it has any role at all – and the demanding search for systemic causes begins.

1.3 The idea of feedback

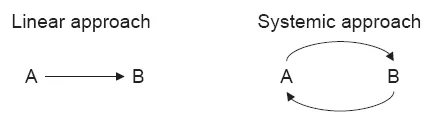

The idea of ‘feedback’ in systems is the prime mover in understanding a problematic situation holistically. This seemingly simple concept opens the door to quite sophisticated understanding. The basic conceptual unit of feedback is the ‘feedback loop’, that is, a closed chain of causal relationships that feeds back on itself. In general, whenever it is linearly postulated that A causes or affects B, a systemic approach looks for the ways in which B might in turn affect A, as shown in Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1 Linear causation and systemic feedback

There are two types of feedback. Negative, or controlling, feedback aims towards some steady state. Positive feedback is self-reinforcing, either in terms of growth (regenerative dynamics) or deterioration (degenerative dynamics), both of which, in the absence of negative feedback, ultimately lead to the collapse of the system. Consider the following two examples, the second of which illustrates how a systemic problem-solving approach differs from one reduced to blame, anger appeasement and the linear search for causes.

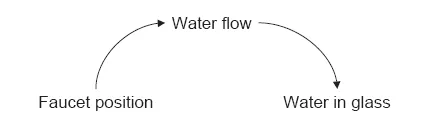

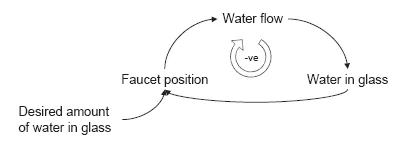

The first example, that of a negative feedback system, can be illustrated through the workings of a water faucet. A faucet is turned to control the level of water in a glass, as shown in Figure 1.2. The level of water in the glass and the desired level to be reached both determine the faucet position at any one time, so that the water in the glass ultimately reaches the desired level, as shown in Figure 1.3.

Figure 1.2 Water flowing into a glass

Figure 1.3 Negative feedback loop

In this example, the feedback serves to control the system, enabling it to reach some desired state, some goal. It is a feature of negative feedback loops to be goal-seeking in this way. Negative loops act to adjust systems towards equilibrium points or goals, just as a thermostat loop adjusts room temperature to a desired setting.

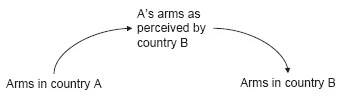

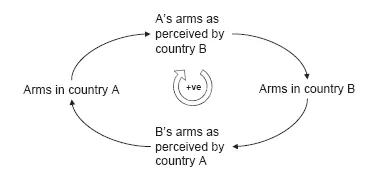

A positive feedback system is the kind of system which requires systemic change, or redesign, based upon consensus but which instead easily falls into blame politics. Any arms race illustrates this type of system feedback. A country acquires more armaments to catch up with the competition, as in Figure 1.4. This effectively generates more armaments for the competition, as shown in Figure 1.5.

Figure 1.4 Arms in country B influenced by perceived arms in country A

Figure 1.5 Positive feedback loop

Positive feedback loops may be seen as vicious circles which reinforce themselves more and more. They may also be seen as growth circles and evolutionary circles. Ultimately, with no negative control mechanism, the system collapses. Of course, most systems are constituted by a multitude of interconnected positive and negative feedback loops and their behaviour is rooted in a complexity which makes it difficult to see what causes what. A number of methodologies, quantitative and qualitative, exist to facilitate the navigation of such complexity (Sterman, 2000; Eden and Ackermann, 1998).8

1.4 ‘We have the war we deserve’

The concept of feedback is useful because it allows the linking of causal structure with dynamic behaviour. For example, the structure of the system, as causes and effects, of Faucet position – Water flow – Water in glass is analysed within the dynamic behavioural context of the faucet changing as the water in the glass changes. Undesired behaviour in the system can be controlled by identifying the structural reasons and intervening in the feedback loops.

This usefulness is, however, trivial when compared to the more powerful aspect of the feedback concept – that aspect which dissolves any talk of blame and focuses the mind on a truly systemic approach to resolution. For the truly profound insight is the way the system, through an explication of its feedback loops, begins to reveal how it causes its own behaviour. Country A, for instance, perceives the arms race as ‘caused’ by country B and vice versa. It could equally well be claimed, however, that country A causes its own arms build-up by stimulating the build-up of country B. More accurately, there is no single cause, no credit or blame: the relationships in the system make an arms race inevitable. A and B are helpless puppets – until they decide to redesign the system, and this calls for consensus.

Another example where the systemic approach highlights the essence of a problem and thus goes beyond blame consists in the periodic increases of the oil price. Rises that are blamed on OPEC could equally be blamed on the heavy consumption of the non-OPEC countries – but, more accurately, the price rises are an inevitable result of a growing economic system dependent on a depleting non-renewable resource base. Similarly one can say that the business world constitutes a system that is structured to generate recessions and depressions; or that the decisions of farmers make fluctuating commodity prices inevitable; or that the flu does not invade one – one invites it. In the words of Jean-Paul Sartre (1958: 555): ‘we have the war we deserve’.

Seeing the source of a problem within...