![]()

Part One

Conceptual and Empirical Foundations

![]()

Chapter 1

Conceptualizing Death and Trauma: A Preliminary Endeavor

B. Hudnall Stamm

DEATH AS A TRAUMATIC STRESS RISK FACTOR

Internationally, the overall death rate ranges from 18 per 1,000 (West Africa) to 6 per 1,000 (East Asia), with most countries around the 9–11 per 1,000 range (figures for 1989; Aiken, 1991). In the United States and Canada, 14%-18% of pregnancies end in the spontaneous death of the fetus (Neugebauer et al., 1992). Infant mortality ranges from a low of 4.8 per 1,000 live births in the most developed countries to 161 per 1,000 in the least developed countries (World Health Organization [WHO], 1995).

Death is not a rare event. Yet, by best estimates, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), the hallmark traumatic stress disorder, is not common. Nearly everyone experiences the death of a loved one. About 55% of the people in the United States are exposed to an event that would qualify as an extreme stressor according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV; American Psychiatric Association [APA], 1994, p. 428). Yet, the estimated nonclinical population lifetime PTSD prevalence rate is only 7.8% (Kessler et al., 1995). What range of reactions might there be that could account for differences between exposure and the development of a disorder?

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder, Traumatic Stress, and Death

Until 1994, PTSD required experiencing of “an event that is outside the range of usual human experience and that would be markedly distressing to almost anyone” (APA, 1987, p. 250). This formal medical diagnosis dominated our understanding of traumatic stress for nearly two decades. However, since most people experience the death of someone with whom they were close, death per se cannot be described as “outside the range of usual human experience.” Some argue it is unlikely that “ordinary” death could serve as a stressor that has the potential to produce PTSD (cf. Zisook & Schuchter, 1992). Others argue that while grief and trauma are not the same thing, the same event has the potential of producing either or both experiences (cf. Eth & Pynoos, 1985, 1994; Pynoos & Nader, 1988).

The original definitions of traumatic stress led to considerable wrangling about what events actually qualified as “traumatic” (APA, 1987). The DSM-IV definition of traumatic stress shifts the focus from a list of qualifying events to key elements of the event. Under the new criteria, a person must have “experienced, witnessed, or been confronted with an event or events that involve actual or threatened death or serious injury, or a threat to the physical integrity of oneself or others” (APA, 1994, p. 426). Thus, death, either as reality or threat, is the pivotal aspect of the definition. The second element—”the person’s response involved intense fear, helplessness, or horror” (APA, 1994, p. 426)—opens new understandings of death as a traumatic stressor.

The event-only perspective of traumatic stress has been abandoned. Traumatic stress is an interaction between the person and the event. Because of the bifold nature of the definition, it is possible for death, even if it is sudden or violent, to be traumatic or nontraumatic based on the response of the person who is experiencing the loss. By definition, if the experience is traumatic and leads to a diagnosable pathology, the individual must have reacted with intense fear, helplessness, or horror.

Many of the experiences reported by the bereaved are similar to those that are associated with stress reactions and PTSD. Those reports can include (a) recurrent and intrusive recollections; (b) recurrent distressing dreams, flashbacks, and other dissociative experiences; (c) psychological distress at exposure to symbols of the event or the deceased, including anniversary date distress; and (d) physiological manifestations such as difficulty with sleep, irritability, and difficulty concentrating (APA, 1987, 1994; Eth & Pynoos, 1985; Glick, Weiss, & Parkes, 1974; Jacobs, 1993; Nader, Pynoos, Fairbanks, & Frederick, 1990; Rando, 1992, 1994; Trice, 1988; Trolly, 1994; Turnbull, 1986). Burnette and colleagues (1994) surveyed 77 international experts in the field of thanatology. The consensus from this group was that, even in normal bereavement, it is common to observe yearning and the need to talk about the lost person. These behaviors are accompanied by intrusive thoughts about the lost person, as well as preoccupation and distress at reminders of the person. Clearly, many of these symptoms overlap with even the most strict definition of traumatic stress (APA, 1994). Yet, the question remains, Do these symptoms mean that the person has PTSD?

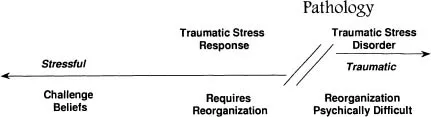

As stated elsewhere (Stamm, 1995; Stamm & Friedman, in press), traumatic stress can be envisioned as a part of the larger concept of stress, which can include, but is not limited to, the mental disorders of acute stress disorder and PTSD. I suggest that stressful experiences can be conceived as an individual’s experience in relation to an event, such that elements of that event in combination with that specific individual create a situation whereby the experience itself is stress producing and one’s beliefs—of faith in life, in others, in self—are disorganized, reFstructured, or at least challenged (Stamm, 1993). The key differentiation between a traumatically stressful experience and a stressful experience is the demand for reorientation (Stamm, 1995; Stamm, Catherall, Terry, & McCammon, 1995). Experience-induced reorientation is stressful but may or may not cause a diagnosable traumatic stress-related mental disorder.

Figure 1.1 Conceptualization of traumatic stress.

In fact, it is unlikely that people would change at all without some stress to act as a motivator. Positive as well as negative changes can be stressful. This raises the question as to whether stress is a single continuum ranging from minor to extreme stress or whether traumatic stress is a categorically different experience. At present, there is insufficient scientific evidence to answer this question absolutely, but ongoing biological research holds promise (e.g., Friedman, Charney, & Deutch, 1995; Perry, 1993). Figure 1.1 (Stamm, 1995) suggests the nature of this theoretical assumption.

According to the conceptualization shown in Figure 1.1, death is a stressful experience that may or may not lead to a traumatic stress disorder. Death from extreme stressors such as disaster, war, starvation, or genocide is a potent risk factor for traumatic stress responses. These kinds of events seem to demand restructuring of one’s belief system (Janoff-Bulman, 1992; McCann & Pearlman, 1990; Stamm, 1995). However, even the “timely” death of another leaves those who have experienced the irrevocable physical loss in a situation in which it is virtually impossible to continue life as if no change has occurred.

This does not mean that all death experiences lead to PTSD or even traumatic stress. Some would even argue that it is possible to experience the death of another without feelings of serious distress (cf. Wortman & Silver, 1989). But some restructuring is nearly always necessary. Following a death, at the very least, someone who was previously a part of the person’s life is no longer physically present. For example, after the death of a parent, a bereaved woman remarked that she had to remind herself that her grocery purchases were no longer dictated by what she thought her sick mother might be able to eat. Although this was a simple accommodation—which the woman did not consider aversive—it was nonetheless an accommodation.

In summary, this chapter proposes that death is a stressful life experience that can produce a situation ripe for a traumatic stress response that may or may not lead to a traumatic stress disorder. In addition, the assumption is made that stress reactions are not always ultimately injurious. Challenges to our sense of self and the world are catalysts to growth. They create opportunities for developmental enhancement unless the person-event interaction leaves the person with insufficient personal resources to meet the challenge. In this case, a pathology may develop.

This is, in fact, what the literature would suggest. For some, little or no accommodation is necessary (cf. Wortman & Silver, 1989), while others face a difficult and long-term process (cf. Corr, Martinson, & Dyer, 1985; Jacobs, 1993; Rando, 1992, 1994). Painful change is not inherently bad, and, in fact, it may ultimately bring positive maturity (Janoff-Bulman, 1992; Lazarus, 1966; Lazarus & Folkman, 1984; Stamm, 1995; Stamm, Varra, & Sandberg, 1993). Regardless of the course of the experience, death is a reality. At the very least, it signifies a change in the physical constitution of an individual’s or family’s psychosocial constellation (Turnbull, 1986).

Stressful Experience, Traumatic Stress Reaction, and Traumatic Stress Disorder

While no paper can ever address the full context of even a single experience, the point of this chapter is to create a window to the larger picture of death as a stressful experience and glance across the death and trauma literature. People live in a biopsychosocial context; stressful events are not isolated from the person who experiences them. The change from the DSM-III-R event-centered PTSD definition to the DSM-IV person-event interaction definition clearly recognized the importance of contextualizing stressful experiences. This chapter endeavors to raise the question of stressful experiences as an ecological, contextual issue so that we might learn to prevent the abortive growth process of PTSD and enhance the possibility of positive developmental growth in the face of the inviolate change of death.

The term stressful experience (Stamm, 1995; Stamm, Bieber, & Rudolph, 1996; Stamm, Varra, & Sandberg, 1993) recognizes this person-event interaction at the broadest and most encompassing level. Two other terms originated by Figley (1985, 1995) have been adapted for use here. The term traumatic stress reaction refers to “the natural and consequent behaviors and emotions … [as] a set of conscious and unconscious actions and behaviors associated with dealing with the stressors” or memories of the experience (Figley, 1985, p. xix). An important underlying assumption made is that a traumatic stress reaction contains within it an element of event-induced demand for reorganization of one’s belief system (Stamm, 1995). Traumatic stress disorder (Figley, 1985, 1995) indicates those stressful experiences that are so traumatically stressful and place such high demands on the person for change that the person’s psychosocial resources are challenged sufficiently to create pathology (Stamm, 1995). Following the prevailing professional thought, pathology is defined as a diagnosable mental disorder according to criteria of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (American Psychiatric Association) or the International Classification of Diseases system.

Traumatic Stress Other than Acute Traumatic Stress Disorder and PTSD

Traumatic stress disorders may take a variety of forms, including PTSD, which has been the focus of great attention over the past two decades. As we have come to know it better, we are more able to see the other idioms of distress (e.g., Friedman & Jaranson, 1994; Friedman & Schnurr, 1995; Kessler et al., 1995; Stamm & Friedman, in press). There is a compelling and expanding literature on these other responses. Perhaps the most developed is dissociation (Kluft, 1988; Spiegel, 1991; Steinberg, 1997; Terr, 1991). Depression is frequently seen as comorbid with PTSD and often alone following a stressful event (Kessler et al., 1995). Physical diseases and somatization are gaining recognition as well (Friedman & Schnurr, 1995; Stamm & Friedman, in press).

IDENTIFYING THEORETICAL TOOLS ACROSS DEATH AND TRAUMA

According to Lifton (1967), death is the ultimate confrontation with one’s own mortality. It is, in a sense, the best material for demanding change of one’s beliefs. After one confronts the possibility of death, it is no longer possible to assume invulnerability and innocence. The person must either deny the reality of the experienced death or restructure his or her world to incorporate the experienced information that human life is finite. If denial or repression is not used to keep awareness of the death at bay, the death experience requires some reorganization of one’s understanding of oneself as well as the manner in which one lives in the world.

There are many useful theories that can assist us in understanding death as a medium to challenge one’s beliefs, perceptions, and expectations. To that end, three theoretical perspectives are reviewed briefly here: (a) world assumption theory (Janoff-Bulman, 1992), (b) constructivist self-development theory (McCann & Pearlman, 1990a), and (c) the dimensions of grief summarized by Jacobs (1993), Stroebe and Stroebe (1987), and Turnbull (1986). These three perspectives, along with practice and research, have informed the development of the quantitatively derived Structural Conceptualization of Stressful Experiences (SCSE), designed as a metatheoretical model to address the range of stress responses, from mildly challenging to traumatically stressful (Stamm, Bieber, & Rudolph, 1996; Stamm, Varra, & Sandberg, 1993).

World Assumption Theory

World assumption theory (Janoff-Bulman, 1992) is based in clinical experience and quantitative research with general populations and trauma victims. It proposes that we have three fundamental assumptions about ourselves, the external world, and the interaction between the two. The assumptions are that (a) the world is benevolent, (b) the world is meaningful, and (c) the self is worthy (Janoff-Bulman, 1992). However, as one gains knowledge and accumulates experience, these assumptions seem naive and become increasingly illusory. Traumatic events accentuate this process. Ultimately, it becomes necessary to deny life experiences or to restructure one’s assumptions along the lines of one’s experiences. This requires cognitive reappraisal of the meaning of the negative event.

Traumatic victimizations are unwanted and unchosen. Yet, the ...