- 176 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Hydraulics for Operators

About this book

This important new reference addresses the principles and calculations dealing with the hydraulics of water systems. Hydraulics for Operators includes what is necessary for a basic understanding of water and wastewater utility operations, and it emphasizes practical applications of these principles. This practical reference covers a wide variety of important subjects such as mass density and flow, pressure, open channel flow, pumping, friction loss, and flow measurement.Hydraulics for Operators is loaded with graphics, and sample exercises are included to ensure this new book is an easily understood reference. It is a must for your operator library.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Subtopic

Gestión medioambiental1

mass, density and flow

mass & weight

Mass is the quantity of matter that a substance containspurposes mass and weight are the sameand may be registered asand may be registered as. It is a basic property of the substance, and is constant, regardless of location. Mass is most frequently registered in units of grams, or pounds; it is measured with an analytical balance which compares it against a known mass.

Weight is the effect of the force of gravity upon a substance, and is measured with a scale. A block of steel which weighs ten pounds on earth, will weigh much less on the moon, where gravitational forces are less. Its mass, however, will be the same in both places.

Since we are dealing only with earthly water systems, for our purposes mass and weight are the same quantity.

density

Also called SPECIFIC WEIGHT, density is mass per unit volume, and may be registered as lb./cu.ft., lb./gal., grams/cu.meter. Taking a fixed volume container, filling it with a fluid, and weighing it, we can determine density of the fluid (after subtracting the weight of the container).

temperature

The density of materials is affected by temperature. Many solids expand when hot. Fluids also become less dense when warm. Water has the peculiar property of being most dense at four degrees Celsius. Above and below that temperature, it expands. This accounts for seasonal turnover in lakes, and the formation of density gradients, or layers, in reservoirs and behind dams, often concentrating pollution at specific depths. In settling tanks and clarifiers, this effect can inhibit uniform mixing of influent water, causing short circuiting. Most solids will settle more effectively in warm waters than in cold waters because the water is denser when cold.

pressure

The density of most liquids is not affected by pressure. For all practical purposes, water is considered an incompressible fluid; 62.4 pounds of water occupies a volume of one cubic foot, regardless of the pressure applied to it.

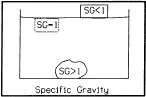

specific gravity

This value designates the ratio of the density of a substance, compared to the density of a standard substance. For liquids and solids, the standard chosen is the weight of water. Therefore:

If the Specific Gravity of water were to be determined this way, we would write:

Substances with a Specific Gravity of less than 1 will float (gasoline, styrofoam, wood, wastewater scum). Substances with a Specific Gravity of more than 1 will sink (bricks, steel, grit, floc, sludge). A good example of treatment process taking advantage of different Specific Gravities is the multi-media filter. During backwash, the different grades of media are mixed up, but at the end of the backwash cycle, as the water quiets, the media layers become separate and distinct: anthracite on top, sand in the middle, garnet on the bottom. These substances are chosen for filtration partially because of their different Specific Gravities.

An anaerobic digester is another good example of the effect of Specific Gravity. Separation of solids, liquid and gas is essential to operation, so that each can be drawn off separately.

displacement

A solid submerged in a body of water will displace its own volume. The displacement causes a rise in water level equivalent to the volume of the submerged object. An object partially submerged displaces a volume of water equivalent to the volume of the section.

Sometimes it is useful to know the volume of an irregularly shaped object. This can be determined by measuring the displacement. For example, to calculate the percent volume of mudballs in a sand filter, take a core sample with a small cylinder of known volume. Extracting a portion of media, sift out the sand, leaving only the mudballs. Pour them into a large graduated cylinder, filled to a liter with water. A volume of water will be displaced in the cylinder equivalent to the volume of the mudballs. Record the milliliter rise in the cylinder, divide by the volume of your core sampler, and you have your percent mudballs - in your sampler, and in your sand filter.

flow

Flow is the quantity of water passing a point in a given unit of time. Think of it as a volume - which is moving. Flow can be recorded as gallons/day (gpd), gallons/minute (gpm), or cubic feet/second (cfs). Flows treated by a municipal utility are large, and usually referred to in Million Gallons per Day (MGD).

Flow may be enclosed in pipes, or it may be open channel flow. The first five chapters of this text will be considering predominantly closed pipe flow. Pipes are flowing full, and under pressure. Open channel flow deals with conduits which are partially full, where the water surface is in contact with atmospheric pressure (streams, aqueducts, sewer pipes, grit chambers, clarifiers). The water flows because of the slope of the conduit. Open channel flow will be taken up later in the text.

Flow may be laminar or turbulent. Laminar flow only occurs at extremely low velocities. The water moves in straight parallel lines, called laminae, or streamlines, which slide upon each other as they travel, rather than mixing up. Turbulent flow, which is normal pipe flow, occurs because of friction encountered on the inside of the pipe. This throws the outside layers of water into the inner layers; the result is that all the layers mix and are moving in different directions, and at different velocities. Added up, however, the direction of flow is forward.

Flow may be steady or unsteady. We will be considering steady state flow only. At any one point, the flow, and velocity, does not change. Most hydraulic calculations are done under the assumption of steady state flow. If we can assume a given flow at a given point, calculations can be based on that fact. If we had to consider that the flow was constantly changing, calculations would become extremely complex.Note, however, that in actual systems, flow is frequently in an unsteady condition. As a water tank empties into a pipe, the flow through the pipe decreases over time, because the depth of water in the tank which pushes the water forward is decreasing. As a pump fills a tank from a bottom entrance, that pump is delivering less water as the tank gets fuller and fuller. Flow through a wastewater treatment plant is constantly fluctuating, but process treatment units are designed for an average, maximum or minimum flow, depending on the need. We realize that unsteady flow is a common condition, but we do not bring this into calculations.

equation of continuity

Under the assumption of steady state flow, the flow that enters the pipe is the same flow that exits the pipe. It is continuous. Water is incompressible; it cannot accumulate inside. The flow at any given point is the same flow at any other given point on the pipeline. This is true in any water system, as long as no additional flows are added, and no exits which split or divert the flow away in other directions are present.

However, the velocity of the water may change. At a given flow, the velocity is dependent upon the cross sectional area of the conduit. Velocity is the speed at which the flow is traveling. A given quantity of water will travel faster through smaller spaces, and slower through larger spaces. Consider this phenomenon in a closed pipe. A 50 gal./min. flow travels at a very slow velocity through a 36 inch diameter pipe, but if the pipe narrows to 4 inches diameter, that same 50 gal./min. will be moving very fast through the narrow section, in order for the flow to remain the same.

The principle applies equally to open channel flow. Water entering a wastewater treatment plant travels at scouring velocity coming down the pipe (2-3 ft./sec.). Entering the grit chamber, which is larger in cross sectional area than the sewer pipe, the veloci...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- 1 MASS, DENSITY AND FLOW

- 2 PRESSURE

- 3 BERNOULLI’S THEOREM

- 4 PUMPING - INTRODUCTION

- 5 FRICTION LOSS

- 6 OPEN CHANNEL FLOW

- 7 FLOW MEASUREMENT

- 8 CENTRIFUGAL PUMPS

- EXERCISES

- GLOSSARY

- BIBLIOGRAPHY

- INDEX

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Hydraulics for Operators by Barbara Hauser in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Tecnología e ingeniería & Gestión medioambiental. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.