![]()

1

The Supreme Court

The Nation’s Balance Wheel?

As Senator Barack Obama strode across the stage to deliver the keynote address at the 2004 Democratic National Convention, probably no one in the audience (including Michele) thought they were looking at his party’s 2008 presidential nominee. Even as he left the stage to thunderous applause from the energized conventioneers, it is safe to think that no one seriously entertained the notion that this man would be taking the oath of office as the 44th president of the United States just four and a half years later. Sure, newspapers across the country would call him “presidential timber,” but more for 2012 or 2016 or beyond.

Against the odds, Senator Obama secured the 2008 nomination of his party. Affordable comprehensive health care would become a central plank of his campaign platform (Rom 2012). After he took office, the president set out to fulfill this particular campaign promise. The Framers of the Constitution set up an elaborate political structure that makes passing comprehensive legislation of this ilk very difficult. And so-called “Obamacare” was a classic reflection of these problems. After numerous procedural tactics, and in a vote that largely fell along party lines, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act passed both houses of Congress and was signed by the president on March 23, 2010 (Sinclair 2012).

By the time the act passed, however, public opinion had turned against the plan. The Democrats suffered major losses during the midterm elections in 2010, ceding control of the House of Representatives in the process (Rom 2012). A number of Democrats who supported the health care act were defeated in their bids for reelection. A chastened President Obama told the country that he heard its concerns and suggested he would trim his legislative sails going forward. The emboldened Republicans sought to repeal the act. By the November 2012 election, House Republicans had called for votes to rescind the health care provisions over 30 times. Each time the Senate, narrowly controlled by the Democrats, refused to go along. With the president’s ratings in decline, public opinion split (but narrowly in favor of repeal), and Republicans smelling a return to the White House, a number of states and businesses decided to use the courts to challenge the provisions of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act.

The thesis of this book is that the Supreme Court makes its decisions in a complex, sometimes highly-charged environment that provides some opportunities but is fraught with constraints. The story of the Affordable Care Act decision—known as National Federation of Independent Business v. Sebelius (2012) in Constitutional Law textbooks—is not the narrative of the typical Supreme Court case, but the factors that influenced the justices and helped shape the decision are prevalent more often than they are absent. As is often the case, the factors did not line up simply in one direction.

The Supreme Court case assessing the constitutionality of the Affordable Care Act involved the entire array of factors that can affect the judicial branch. As a prelude to a full consideration of all the influences on judicial decision making, let’s examine the dynamics—political and legal, internal and external to the Court—that provided the context for this case and the ultimate decision: the president, Congress, lower courts, public opinion, and the law.

For many analysts of the Supreme Court, the most important factor is the sincere policy preferences of the justices (Segal and Spaeth 2002). Five of the justices who would decide the Obamacare case were Republican appointees, and the other four had been nominated by Democrats. While pundits may have disagreed about who would win the case and the ultimate scope of the decision, everyone felt it would be a close vote.

Other analysts believe that the Supreme Court’s position at the apex of the judicial system underlines the importance of the law and precedent in determining the outcome of cases (Bailey and Maltzman 2011). The extant precedents on the eve of the oral arguments in the Affordable Care Act case seemed to favor the law. Congress had passed the act pursuant to its authority under the Commerce Clause. 1 Most of the Commerce Clause decisions over the past 70 years had favored a broad interpretation of congressional power.

Like all issues before the Court, the case would not be argued nor the decision rendered in a vacuum. The decision was birthed against the backdrop of a presidential election. The justices had to understand that the Court’s decision would alter the arc of the election process. This had to be an additional burden or constraint on the Court. Would it give the justices pause in making their decision? Might the Court expand its deference to the elected branches? In a normative sense, the Court is often urged to exercise judicial restraint. That restraint can be manifested in following existing precedent and/or acting strategically by showing deference to the elected branches (Bailey and Maltzman 2011; Pacelle 2002).

In defending the creation of the judicial branch, Alexander Hamilton referred to the Court as the “least dangerous branch of government” (Federalist 78). In his view, the Court would need to tread carefully and exhibit judicial self-restraint because it would be dependent on the other branches of government for support. The judicial branch had neither the “sword nor the purse” so it would need to rely on the good offices of the elected branches of government. In more modern parlance, there is a normative expectation that the unelected justices will not wantonly cast aside the actions of the elected branches (Pacelle 2002).

Some analysts argue that strategic factors, most notably the policy positions of the other branches, influence the Court (Epstein and Knight 1998; Eskridge 1994; Pacelle, Curry, and Marshall 2011). The president supported the act and sent the solicitor general into Court to argue for the merits of sustaining the law. Every study shows the remarkable success of the Office of the Solicitor General in getting its cases accepted and in winning on the merits (Salokar 1992; Ubertaccio 2005; Pacelle 2003; Black and Owens 2012). But by all accounts, in arguing the government’s position in the National Federation of Independent Business v. Sebelius case, Solicitor General Donald Verrilli did not have his best day. He was sharply questioned by the justices, particularly by Justice Anthony Kennedy, the swing vote on the Court, whose support was considered mandatory for whichever side was going to win.

Congress passed the act that was being considered, but the election of 2010 had shuffled the alignments so that the House now had a majority opposing the enacted bill. The Senate narrowly supported the measure (Sinclair 2012). Both the president and Congress have some important checks that they can bring to bear in any dispute with the Court. The general thought is that the Court may temper its preferred policy position to avoid a costly clash with the elected branches. If the Court stakes out a position that is antithetical to the other branches of government, the elected branches might overturn that decision or, perhaps worse, punish the Court as an institution (Martin 2006; Pacelle, Curry, and Marshall 2011).

The Court’s need to defer to the elected branches, however, was mitigated by two factors. First, the decision was likely going to be based on constitutional grounds. This would largely free the Court from concerns that its ultimate decision would be reversed. It takes an extraordinary majority in both houses of Congress (often in the form of an amendment to the Constitution) to overturn a constitutional decision. Second, the elected branches were not unified in their views of the health care act. The House supported repealing the measure, while the Senate and the president supported it. The bottom line for the justices was that this division was certain to produce at least one ally for the Court regardless of the direction of the decision.

One of the major responsibilities of the Supreme Court is to police the federal judicial system. Because cases get shaped in the lower courts before they show up on the Supreme Court’s docket (Steigerwalt 2010; Baum 2013), the decisions of lower courts can have an impact on how the justices view a case. The Supreme Court is more likely to grant certiorari when the lower courts have made conflicting decisions in similar cases (Pacelle 1991; Perry 1991). That element was present here. The case that made it to the Supreme Court came from Florida through the Eleventh Circuit. The Eleventh Circuit found the law to be an unconstitutional exercise of the Commerce Clause. The Sixth and the District of Columbia Circuits decided similar cases and each determined that the law passed constitutional muster.

The justices of the Supreme Court are not elected by the public. The Framers did this deliberately to insulate the Court from the reach of public opinion. But can the Court really stand in the face of public opinion and deliver decisions that are at odds with the views of a majority of Americans? (McGuire and Stimson 2004; Casillas, Enns, and Wohlfarth 2011; Hall 2011). Some argue that this is the very reason we need a Supreme Court that is unelected (Pacelle 2002). The National Federation of Independent Business case presented the Court with an unusual circumstance: a relatively clear public response was available to the justices.

There are two forms of public opinion to consider. First, there is the public opinion directed to the particular issue or policy (in this case, whether citizens supported the health care provision). This is typically referred to as “specific support.” The second form is called “diffuse support,” and it refers to what citizens think of the Court as an institution (Caldeira and Gibson 1992; Gibson and Caldeira 1992; Gibson, Caldeira, and Baird 1998; Bartels and Johnston 2013). On the eve of the Obamacare decision, the Gallup Poll showed Court approval rates at 44 percent (with 36 percent disapproval). Across history, that is considerably more negative than usual. The decision would cost the Court some of its support, causing a drop to a favorability rating of 41 percent (Dugan 2013). 2 But as we will see in Chapter 5, the overall long-term “diffuse support” for the Court as an institution remains considerably higher than the specific support attached to particular decisions (Gibson 2007; Gibson and Caldeira 2009).

If we take a step back and evaluate the potential influences on the Court, they could easily justify a decision in either direction. Five justices are generally considered conservatives, suggesting a decision striking the law if sincere policy preferences were the rationale for the decision. On the other hand, Chief Justice John Roberts has advocated judicial restraint and deference, and his Court has exhibited less activism in striking down laws of Congress than the previous Rehnquist Court. The Court might show deference to the elected branches and uphold the health care provisions. Precedent generally supported the broad use of the Commerce Clause, so that was another factor supporting the law.

The strategic variables, the president and Congress, generally supported upholding the law. But some analysts argue that the Court responds not to the Congress that passed the law but to the sitting Congress (Eskridge 1994). If that is the case then the changes in the House and the constant attempts to repeal the law would send a clear message to the Court. In general, the constitutional basis of the case coupled with the occurrence of divided government after the midterm election of 2010 might remove some of these constraints from the calculus. If the Court were to follow public opinion, it would strike the law down.

Of course we all know that the Court narrowly upheld the health care law. The decision was considered surprising in one respect: the identity of the key fifth vote. Moderate conservative Anthony Kennedy, who is typically the Court’s swing vote, supported striking the law down. As expected, the four most liberal justices supported the health care law. The three most conservative justices voted to strike the law. Chief Justice Roberts provided the key fifth vote to sustain the law. This seemed to be at odds with his sincere ideological preferences. Roberts’ opinion struck the chord of judicial restraint. It was not the province of the unelected justices to tamper with the policy decisions of the elected branches of government. That was the job of the people through their ballots. Some also posit that the public support for the Court, already at relative ebb, was an important factor in Chief Justice Roberts’ decision to support the act. Roberts may have felt that the Court would lose more specific and diffuse support if it struck down a visible act.

When the pundits and political analysts attempted to deconstruct the factors that led to President Obama’s reelection victory, many focused on the Court’s surprising decision to uphold the Affordable Health Care Act. President Obama could thus campaign on his major legislative achievement, which has been referred to as the most important legislation in a generation (Rom 2012, 160).

The “law” and judicial restraint seemed to trump the personal preferences at least for one justice and, as a result, for the Court as an institution. The case illustrates that Supreme Court decisions can be very important. They require the justices to balance legal and political considerations. This book examines the environment that the Supreme Court operates in and the complex calculus that justices, as individuals, and the Court, as an institution, undertakes even when it makes a decision in less noteworthy cases, balancing the law, respecting the prerogatives of the other branches, and remaining attuned to the lower courts and public opinion.

The Design of the Framers and the New Normal

The Framers of the Constitution constructed a plan for government that would decentralize power. At the national level, the mechanisms were separation of powers and checks and balances. The results were a bit skewed, though. Congress, as befits its position in Article I of the Constitution, was to be the strongest branch of government. The Framers feared an executive branch that was too strong, but they animated the president with some range of power. The judicial branch, however, seemed to be an afterthought. If the three branches were not quite co-equal, the judiciary was the least equal, hence the sobriquet “least dangerous branch of government.”

It certainly seemed that Congress and the president had all the checks over the Supreme Court, while the Court lacked any significant countervailing authority against its institutional rivals. The main authority of the Court as we now see it, the power of judicial review, was nowhere to be found in the Constitution. There is evidence that the Framers addressed the issue of judicial review and explicitly rejected it (Nelson 2000, 2–4). Rather the Supreme Court would create this power for itself in Marbury v. Madison (1803).

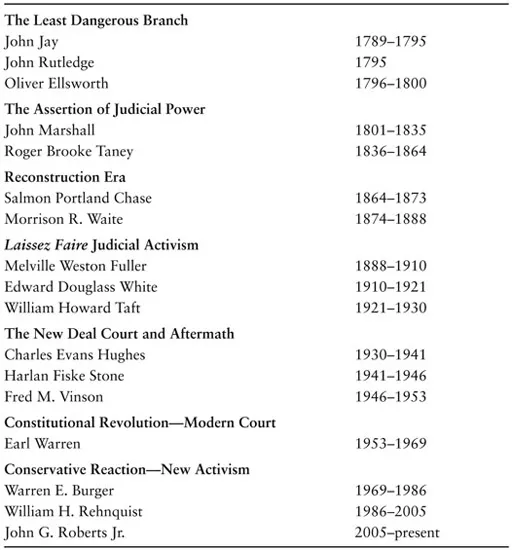

Table 1.1 The Supreme Courts Identified by Chief Justice

If the Supreme Court was the “least dangerous branch of government,” it is clearly no longer so hamstrung. Table 1.1 shows the various Supreme Courts through history. For the most part, we identify a Court by its Chief Justice. The Jay Court was a weak ancestor of the modern Court. Chief Justice John Marshall breathed life into the institution through decisions like Marbury. The Marshall Court’s landmark decisions in Martin v. Hunter’s Lessee (1816), McCulloch v. Maryland (1819), and Gibbons v. Ogden (1824), helped define federalism and gave renewed power to the central government (Newmyer 2001). The power of the Court was cyclical. Occasionally the Court would ignore its constraints and overstep its bounds and pay a significant cost. The Taney Court’s decision in Dred Scott v. Sanford and the Hughes Court’s running battle with the New Deal and state attempts to combat the Depression have been referred to as self-inflicted wounds for the judiciary.

With its decision in Brown v. Board of Education (1954), the modern Court was birthed (Pacelle, Curry, and Marshall 2011). The decision fulfilled a promise that the Court made when it issued the “preferred position” doctrine over a decade earlier. In the wake of a series of decisions declaring major portions of the New Deal unconstitutional, the Court found itself in a precarious position. The judicial war on the New Deal incurred the ire and the wrath of President Franklin D. Roosevelt. In response Roosevelt proposed the “Court Packing Plan.” The Court capitulated and announced its intention to treat economic cases with deference, bowing to the will of the president and Congress. The Court would exercise judicial restraint in these cases. But in redefining its institutional role, the Court would be proactive in dealing with civil liberties and civil rights. When it came to the rights of insular minorities, the Court would opt for judicial activism, thus putting these issues in a preferred position (Pacelle 1991).

In the wake of Brown v. Board of Education, the Warren Court launched a constitutional revolution in civil liberties and civil rights (Powe 2000). Despite the claims of various nominees and chief justices, it has been impossible to put the genie back in the bottle. The Court is now effectively a major policy maker, but its decisions do not occur in a vacuum. The Court must rely on the executive branch to implement its directives and on Congress to fund them. Presidents and members of Congress may be buoyed by Court decisions, or they may earn political capital with the voters by treating the judiciary as a whipping boy for unpopular decisions (Murphy 1964; Epstein and Knight 1998; Canon and Johnson 1999; Bamberger 2000).

This book examines the constraints and opportunities that help structure decision making by the Supreme Court, as seen in the context of separation of powers. I examine the potential means by which the other branches of government, lower courts, public opinion, and the law influence decision making. In subsequent chapters, I detail the constitutional and practical constraints on the Court. I examine the relationship between the Court and the president, and the Court and Congress. The analysis then considers the influence of the bureaucracy, lower courts, public opinion, and litigants on decision making.

In studyi...