- 168 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Children's Drawings of the Human Figure

About this book

The human figure is one of the earliest topics drawn by the young child and remains popular throughout childhood and into adolescence. When it first emerges, however, the human figure in the child's drawing is very bizarre: it appears to have no torso and its arms, if indeed it has any, are attached to its head. Even when the figure begins to look more conventional the child must still contend with a variety of problems: for instance, how to draw the head and body in the right proportions and how to draw the figure in action.

In this book, Maureen Cox traces the development of the human form in children's drawings; she reviews the literature in the field, criticises a number of major theories which purport to explain the developing child's drawing skills and also presents new data.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Children's Drawings of the Human Figure by Maureen V. Cox in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Developmental Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 | The Meaning of the Marks |

Scribbling

Long before they produce any recognisable pictures, children in most Western cultures make marks on a piece of paper with a crayon or pencil. These first scribbles appear around the age of 12 months, although individual children will be more or less advanced depending on the availability of materials, parental encouragement, and so on. The earliest marks are often rather tentative, even though there are some children who stab at the page with their pencil. Either way, the movements are generally unplanned and uncontrolled. These early attempts may in fact be imitations of the adult’s hand movements as Major (1906) suggested. His son, “R”, seemed reluctant or unable to attempt the task at all without his father’s demonstrations.

It has been argued by Bender (1938) and Harris (1963, p. 228), for example, that children enjoy scribbling primarily because of the motor movement it involves. While not denying that this enjoyment of movement is important, it is clear that the production of marks on the page is also of great interest to the child. If children are given a pencil-like implement that does not leave a mark, they quickly lose interest in the activity (Gibson & Yonas, cited in Gibson, 1969, pp. 446–447).

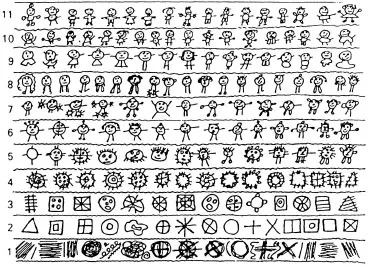

As children gain more experience with the pencil, their scribbles become more distinct and their repertoire more varied. In fact, among her collection of approximately one million children’s drawings, Kellogg (1969) identified 20 different basic scribbles. She claimed that these scribbles are the basic units which are combined and recombined into progressively more complex forms such as diagrams (crosses, rectangles, etc.), combines (units of two diagrams), aggregates (units of three or more diagrams), etc. (see Fig. 1.1). Kellogg argued that there is no indication that these scribbles or designs are meant to be representational, in the sense of “standing for” something in the real world. Indeed, she maintained that the process of combining and recombining the scribble formations is not determined at all by the visual world, but by the child’s sense of aesthetic balance, which in itself Kellogg takes to be innate and universal. When the child eventually does come to make representational drawings, she calls on these non-representational forms in her repertoire, and so her human figure drawings owe more to those earlier forms than they do to the visual characteristics of real people. The mandalas (see level 3 in Fig. 1.1) and sun schemas (level 4) in particular are the basic designs which children typically employ in their first attempts at human figure drawing.

Fig. 1.1 Kellogg (1969) suggested that the child’s human figure drawings evolve from earlier scribbles and patterns.

An Evaluation of Kellogg’s Theory

This “building block” notion of the development of drawing emerged from Kellogg’s study of her vast collection of children’s spontaneous drawings. Although, from other data too, there does appear to be an age-related shift from early uncontrolled scribbles through more distinct forms to later representational forms (r = 0.85: Cox & Parkin, 1986), there is little evidence that all children necessarily go through the same specific and detailed sequence of steps proposed by Kellogg. In fact, Kellogg herself, as Golomb (1981) points out, reports a very low incidence of forms such as the mandala and the sun schema, which are supposed to be important precursors to the child’s construction of the human figure (the highest percentage of the occurrence of the mandala was 9.62 in the age range 24–30 months and the highest percentage of the occurrence of the sun schema was 4.1 in the age range 49–54 months). Furthermore, the sun schemas and the first human figures appear at the same time (mean age 3 years 7 months), a finding which contradicts the notion of a stage-like progression.

When Golomb (1981) and her co-worker, Linda Whitaker, analysed the scribbles produced by their own 2- to 4-year-olds, they encountered a number of problems in classifying the scribbles according to Kellogg’s 20 basic categories. The main difficulty concerned inter-rater reliability, which was extremely low when the raters scored the finished drawings. It rose to 70%, however, when the raters watched the whole process of the child’s scribbling, but still only two broad categories of scribble could be identified: (1) whirls, loops and circles and (2) multiple densely patterned parallel lines.

There is also other evidence which casts doubt on Kellogg’s stage hypothesis. This comes from a number of studies (e.g. Alland, 1983; Gardner, 1980; Harris, 1971; Millar, 1975) in which children or adults have, for various reasons, been previously deprived of the opportunity to draw. Despite this, they quickly move from scribbling “exercises” to drawing recognisable human forms without passing through the stages suggested by Kellogg. Golomb (1981) also notes that 39% of her 2-year-old scribblers and 80% of her 3-year-old scribblers produced a representational picture on request, or dictation by the experimenter, even though they had not progressed through Kellogg’s sequence of supposedly pre-requisite stages.

Early Non-Pictorial Representations

In general, then, the evidence does not support Kellogg’s building-block notion of the development from scribbles to recognisable representational forms. But we are still left with the question of what is going on at the scribbling stage. It could be that children are simply developing an understanding of the relationship between their motor movements and the production of the marks on the page and are then deliberately attempting to vary the kinds of marks they produce. While not seeking to deny the importance of these particular functions or outcomes of the scribbling process, there is evidence which none the less points to a representational intention on the part of the scribbling child.

Although it may seem curious to try to advocate such a position when the young child’s scribbles appear, almost by definition, to be non-representational, children do use forms of representation which are non-pictorial and which are not detectable if we consider only the final product of the child’s scribbling exercise. Indeed, Freeman (1972) has pointed out that an analysis based solely on children’s completed drawings or scribbles may give us an incomplete or even a distorted view of their meaning. Thus, if we concentrate on the final product, we may well try to interpret the scribble in terms of its visual likeness to a particular object, and in nearly all cases we shall judge there to be little or no similarity and conclude that the scribble is therefore non-representational. If, on the other hand, we consider the process of the drawing exercise as well as the final product, we may discover that the child is attempting to represent objects or events even though this is not done in a conventional, pictorial sense. Given that very young children from as early as 12 or 13 months (Cox, 1991) are routinely engaged in representational or symbolic behaviour, through language and pretend play for example, it would be extraordinary to find no representation whatsoever in their drawing activities.

The main evidence that non-pictorial representation is a part of the scribbling child’s activity comes from the work of Wolf and Perry (1988) and Matthews (1984). Wolf and Perry note that children, beginning at about the age of 12–14 months, will use the drawing materials themselves to symbolise objects, relationships or events. In these object-based representations, as these researchers call them, a child may, for example, roll up a crayon inside a piece of paper and call out “hot dog”. Also, in the second year, a child may demonstrate gestural representations, again using the drawing materials themselves: One child, for instance, “hopped” a pen across the page, saying “bunny”, and created a trail of dotted footprints. The reference to gestural representations endorses Vygotsky’s (1978, p. 107) assertion that, “In general, we are inclined to view children’s first drawings and scribbles rather as gestures than as drawing in the true sense of the word.”

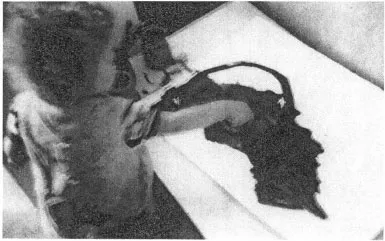

Matthews (1984) gives similar examples of what he calls action representations. Ben, aged 2 years 1 month, rotates his paintbrush on the page producing a continuous series of overlapping spirals (see Fig. 1.2) and describes what is going on: “… it’s going round the corner. It’s going round the corner. It’s gone now.” Matthews argues that Ben is describing the movement of an imaginary object, probably a car, which is symbolised by the tip of the brush. The action is taking place in three-dimensional space and Ben’s commentary draws attention to some of the qualities of the movements within that space (its direction round a corner and its eventual disappearance). It is interesting that Ben’s announcement that the car had disappeared seemed to be made when the line had become submerged under layers of paint and was no longer clearly visible; this suggests that the marks on the page are not merely a by-product of the child’s activity but can guide and alter his interpretation of his actions.

Fig. 1.2 Ben (aged 2 years 1 month): “… it’s going round the corner. It’s going round the corner. It’s gone now.” (Reproduced with the permission of Dr John Matthews.)

Wolf and Perry (1988) argue that these early representational systems commit meaning to paper, although not in the usual pictorial sense, and that they may be important in laying a foundation for later and more conventionally pictorial systems of representation. From about the age of 20 months, according to Wolf and Perry, children are able to make separate marks for objects or parts of objects. So, for example, they may make a mark for a head, another for a tummy, and further marks for the feet of a person. In this point-plot representation, the children are recording the existence of different items, their number (one head, two feet, etc.) and often their spatial position (head at the top of the figure, tummy lower down and feet at the bottom). In this system, there is the first indication that the marks themselves rather than the child’s attendant behaviour (sounds, gestures, etc.) are carrying the meaning, even though there is little or no visual correspondence between the shape of the marks and the shape of the items they stand for.

Fortuitous Realism

Between about 18 and 30 months, children begin to monitor the marks they create on the page and may see pictures in them, such as “a pelican kissing a seal” or “noodles in soup”, to use two examples given by Wolf and Perry. These productions are, of course, accidental; the child has no plan or prior intention regarding the particular subject matter of the drawing. This ability to recognise something in the scribbles was also noted by Luquet (1913; 1927) and referred to aptly as fortuitous realism.

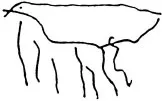

One of the developments which may in fact promote children’s tendencies to notice things in their scribbles is their developing control over the pencil and their ability to make loopy scribbles which bound an enclosed space. The loopy or spiral scribbles become more controlled until the child can curtail the spiral and join the ends to make a rough circle (Bender, 1938; Piaget & Inhelder, 1956). Arnheim (1974) has pointed out the special significance that a circle seems to have: It bounds an inside area which attains a solid-looking quality and is readily recognised as a figure set against a background. In fact, Arnheim regards the circle as one of the most primary percepts. Some children may be able to add further appropriate details to their scribbles once a particular object has been recognised. One child aged 2 years 10 months, expressed surprise after she had drawn a closed shape, saying “Look! That’s a bird!” (Cox, 1991). She then went on to add a dot, saying “He needs an eye”, and a number of lines, saying “They have legs, don’t they? Five legs!” (see Fig. 1.3).

Fig. 1.3 A bird, drawn by Amy, aged 2 years 10 months. (Reproduced with the permission of Harvester Wheatsheaf.)

Pictorial Representation

Towards the end of their second year, children begin to construct forms on the page which have more visual-spatial correspondence to the objects they are intending to represent. Matthews (1984) calls this figurative representation. There may, nevertheless, still be some discrepancy between the children’s intentions and what they actually produce and, although they may not set out to draw a particular object, they may change their minds in mid-drawing if the marks on the page remind them of something else. Soon, however, children develop more reliable means of representing visual-spatial information about objects, which also enables others to recognise readily what they have drawn.

Wolf and Perry (1988) are at pains to emphasise that although there is some developmental emergence of the different ways of representing objects on a page, the systems should not be seen as mutually exclusive and stage-like, since children continue to use and to develop a number of different systems, a point also endorsed by Matthews (1984). A child may in fact combine different systems in the same drawing. Ben, at nearly 3 years 1 month, drew “someone washing” (see Fig. 1.4). There is evidence of figurative representation (to use Matthews’ term) in the drawing of the tap and the two arms of a person reaching into the basin. There is also evidence of action representation in the continuous rotations of the paintbrush, representing the swirling of the hands in the water. Combinations of different systems are also used by much older children who represent the movement or trajectory of a person or a vehicle by single or dotted lines.

Fig. 1.4 Someone washing, drawn by Ben, aged 3 years 1 month. (Reproduced with the permission of Dr John Matthews.)

Although children develop a variety of graphic representational systems and may use them in combination, it is nevertheless the visual-pictorial which becomes dominant in the sense that the child intends to capture some visual aspect of the object—its shape, the proportions and spatial arrangement of its constituent parts, etc. Indeed, Golomb (1981) argues that the main concern of the child who makes the transition from scribbles to representational forms is with visual likeness to the object.

If the child’s intention is to capture some visual likeness to the real object, then the problem becomes one of finding appropriate pictorial ways of suggesting various properties of the object. This process has been described as a “s...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- A Note on Gender

- Introduction

- 1. The Meaning of the Marks

- 2. The Tadpole Figure

- 3. Children’s Modifications of Their Human Figure Drawings

- 4. Human Figure Drawings as Measures of Intellectual Maturity

- 5. Human Figure Drawings as Indicators of Children’s Personality and Emotional Adjustment

- 6. Sex Differences in Children’s Human Figure Drawings

- 7. Human Figure Drawings in Different Cultures

- 8. Overview

- References

- Author Index

- Subject Index