- 208 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

It has often been maintained that young children's knowledge is limited to perceptual appearances. In this "preoperational" stage of development, there are profound conceptual limitations in that they have little understanding of numerical and causal relations and are incapable of insight into the minds of others. Their apparent inability to perform well on traditional developmental measures has led researchers to accept a model of the young child as plagued by conceptual deficits. These ideas have had a major impact on educational programs. Many have accepted the view that the young are not ready for instruction and that their memory and understanding is vulnerable to distortion, especially in subjects such as mathematics and science. However, the second edition of this book provides further evidence that children's stage-like performance can frequently be reinterpreted in terms of a clash between the conversational worlds of adults and children. In many settings, children may not share an adult's well-meaning purpose or use of words in questioning. Under these conditions, they do not disclose the depth of their memory and understanding and may respond incorrectly even when they are certain of the right answer.

In this light, a different model of development emerges with significant implications for instruction in educational, health, and legal settings. It attributes more competence to young children than is frequently recognized and reflects the position that development in evolutionarily important domains is guided by implicit constraints on learning. It proposes that attention to young children's conversational experience is a powerful means to illustrate what they know.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Knowing Children by Michael Siegal in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Developmental Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 What Children Know Before Talking

The answer to the question, “To what extent can young children understand abstract concepts?” is central to research on child development. One view, expressed forcefully by the Swiss psychologist, Jean Piaget (1970), is that young children’s knowledge of the world is largely limited to perceptual appearances and that they are incapable of insight into the minds of others. At their own pace, the vast majority will eventually move out of a stage of development marked by severe limitations on the ability to understand concepts.

Over a period of more than 40 years, Piaget set an agenda for research on children’s knowledge and came up with a wide variety of evidence from observations and interviews. On this basis, he argued that preschool children are generally not capable of operating logically in their thinking and that their stage of development can be best described as “preoperational”. Piaget and his followers maintained that education should have the modest goal of matching the child’s stage level. These ideas have had a major impact on educational programmes. Many people have either accepted the view that young children are not ready for instruction—especially in subjects like mathematics and science—or have claimed that programmes should be designed basically to extend children’s awareness of the world beyond that of thinking about perceptual appearances.

My aim in this book is to demonstrate that young children actually know a good deal about abstract concepts, for example, of causality, and the identity of persons and objects. The apparent contradiction in the evidence is resolved by a very different explanation that focuses on language. My idea is that children are both sophisticated and limited users of the rules of conversation that promote effective communication: sophisticated when it comes to the use of conversational rules in everyday, natural talk; limited in specialised settings that require knowledge of the purpose intended by speakers who have set aside the rules that characterise the conventional use of language. Such situations may often involve children in experiments where they inadvertently perceive adults’ well-meaning questions as redundant, insincere, irrelevant, uninformative, or ambiguous.

There are now experiments where efforts have been made to follow conversational rules in order to ensure that children understand the nature and purpose of adults’ questions. The results demonstrate that children do have a substantially greater knowledge of abstract concepts than Piaget estimated and illustrate what they can achieve with assistance from others upon whom they depend for caregiving and instructions. Such results demand a significant shift in educational implications; for example, if preschoolers are able to understand how effects can be caused by factors that are not visible, they should know that food with an apparently fresh appearance may, in reality, be contaminated. This would warrant placing a greater emphasis on early preventive health education. Similarly, if young children are able to understand relations between parts and wholes as expressed by ratios and proportions, a more intensive instruction in the use of symbolic principles of mathematics would be in order.

MODELS OF DEVELOPMENT AND DEVELOPMENTAL COGNITIVE SCIENCE

Since the young have little experience in communication, those such as Piaget who at times claim that they are limited in the ability to understand concepts must ensure that failure can be attributed to a “deep” lack of ability rather than to some misreading of the experimenter’s intent in asking well-meaning questions. Moreover, children can have a grasp of a concept and properly interpret the experimenter’s intent, yet they may still fail owing to memory difficulties, a lack of familiarity with words or linguistic forms, or a lack of sophisticated motor behaviour. To provide a more accurate characterisation, a model of development is required that proposes a “conceptual competence” implicit within the mind of the child.

This type of model building goes beyond traditional disciplinary boundaries and has been increasingly studied in the field of cognitive science, an amalgam of many disciplines including anthropology, computer science, linguistics, neuroscience, philosophy, and psychology. Linguistics in particular would dictate that any comprehensive study of children’s abilities must take into account their interpretation of conversational rules to ensure that their lack of success on tasks that involve knowledge of abstract concepts cannot be attributed to infringements of these rules.

The tasks designed to test children’s understanding almost invariably require a degree of language comprehension. In this respect, adult experimenters may seek to determine that children have a particular concept through direct questioning or through prolonged questioning on numerous similar tasks. However, ordinarily we do not repeat requests when an answer has already been given. This is a convention or rule of conversation that promotes communication through non-redundant messages. A gap may emerge between the intent of the experimenter (which is to make a certain judgement about what children know) and children’s experience with methods of repeated or other forms of unconventional questioning. In such cases, they may misinterpret these requests as conveying the necessity to respond inconsistently or in an “appropriate” way to satisfy what they perceive as expected. In addition, experimenters may use words which can have different meanings for children than for adults. Because children’s responses on many tasks critically hinge on the interpretation of the use of language, any failures cannot be easily attributed to a deep lack of conceptual ability. A lack of performance may instead be due to children’s “interpretative theory” of the purpose and meanings of linguistic forms used in the experiment.

No doubt a large part of development can be viewed in terms of children’s understanding of language and communication. With increasing experience, an implicit conceptual ability may be expressed more explicitly in words regardless of whether experimenters follow conversational rules.

In my opinion, part of what distinguishes developmental psychology from research with adults in perception, cognition, and social psychology is a methodology specifically directed towards examining children’s understanding of abstract concepts as distinct from their comprehension of language. To demonstrate this understanding requires novel methodologies and clever experimentation.

The matter is further complicated in efforts to establish that the rudiments of abstract concepts may be within the grasp of preverbal infants. Not only do infants lack speech (indeed, the word “infant” itself is derived from the Latin infans, or the unspeaking one) but, given their restricted motor development, we cannot even rely on their searching or crawling to shed light on their understanding. Even so, the use in testing situations of innovative methods of communicating with infants has increasingly revealed their implicit knowledge. As a guiding model, child development is better characterised by development towards the conscious accessibility of implicit knowledge rather than a simple lack of conceptual ability or coherence.

In the 19th century, two prominent theorists found a place for this type of developmental model. Yet in each case, it was not until recently that the more important of their two major propositions has been accorded recognition. First, the German physicist and physiologist, Hermann von Helmholtz (see Warren & Warren, 1968) advocated the empiricist position that, for the most part, children’s perception of the world is not innate but is determined by an unconscious association of ideas in memory that depends on past experience. This is the most enduring legacy of Helmholtz’s writings. It has predominated at the expense of his second proposition that the mechanism for making inferences about these ideas is itself innate. According to Helmholtz, “the law of causation, by virtue of which we infer the cause from the effect, has to be considered also as being a law of our thinking which is prior to all experience. Generally, we can get no experience from natural objects unless the law of causation is already active in us. Therefore, it cannot be deduced first from experiences which we have had with natural objects” (Warren & Warren, 1968, p. 201). On this basis, it has been recognised that young children may be equipped with the ability to make “perceptual” inferences which can be developed through instruction (Bryant, 1974).

The other 19th-century developmental theorist is Charles Darwin (1859). His contribution to experimental psychology cannot be underrated and consists of two major legacies. The first was the emphasis on similarities in the evolution and structure of animal and human behaviour. Accordingly, certain principles of animal psychology have been seen to apply as well to humans (Passingham, 1982). Darwin’s second proposition concerned the diversity of organisms and their adaptive fit with the environment, and has only recently been acknowledged as meriting the more fundamental recognition (Rozin & Schull, 1988). On this basis, biological species may be viewed as constrained to learn adaptive behaviours. In particular, although the idea has yet to be fully exploited, human children may be constrained to learn behaviour such as parenting, predator avoidance, sheltering, and the procurement of nutrients through developing the accessibility of their innate or early abilities (Rozin, 1976b; Rozin & Schull, 1988).

The findings of modern research on preschoolers and children in the early primary school years are foreshadowed in the writings of Helmholtz and Darwin. However, the astonishing performance of infants in experiments provides some of the most graphic illustrations of early implicit knowledge. This research illustrates the degree to which preverbal infants display an abstract knowledge of the world. It sets the stage to examine the understanding of young children who have become conversationalists.

OBJECT PERMANENCE

One of Piaget’s (1954) major claims was that infants are at a “sensorimotor” stage in development. By way of foreshadowing the limitations of preoperational young children, he maintained that infants do not understand objects as permanent entities which continue to exist while out of sight. For Piaget, this basic “object concept” is not achieved until they can reach out to uncover hidden objects. Yet even at 9 months, infants sometimes do not search for an object seen hidden in a new location if they have been used to finding an object in a familiar one. The inability to recover an object in a new place suggests that infants lack object permanence.

Two interpretations of this result are that infants expect that an object does have a permanent existence at the location where it has been previously found or that a formerly successful response will produce the object regardless of where it has been hidden. Alternatively, infants’ searching may be based on their knowledge of the function of a location in which objects can be contained (Freeman, Lloyd, & Sinha, 1980) or on their knowledge that there are many similar objects and these are often duplicated (Bremner & Knowles, 1984). Still another straightforward alternative is that infants possess object permanence but lack the ability to perform co-ordinated actions by shifting the focus of their attention to a new location. If so, their searching behaviour may not be a fully adequate measure of their understanding.

An ingenious study carried out by Renée Baillargeon and her co-workers (Baillargeon, Spelke, & Wasserman, 1985) has shown that infants as young as 5 months of age appear to understand that objects exist when hidden. Babies were “habituated” to a screen that moved back and forth through a 180-degree arc in the manner of a drawbridge until they were used to viewing the action of the screen and became clearly inattentive. Then they were shown a solid block in the form of a box centred behind the screen, and viewed two types of events: one that was possible and one that was not. In the possible event, the screen stopped when the box was hidden. In the impossible event, the screen went right through the space that the box had occupied. The attentive reaction of the infants to the impossible event was taken to illustrate their knowledge that objects continue to exist when concealed. This result is compatible with a proposal made by Kellman, Spelke, and Short (1986): Infants anticipate that the movements of objects are constrained by rigid structures and expect that the unity and nature of objects depends on coherent movement.

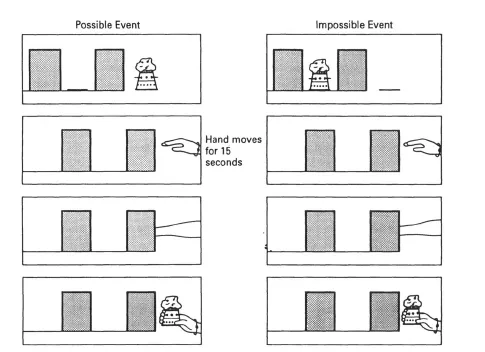

In later experiments, Baillargeon and Graber (1988) examined 8-month-olds’ memory for the location of objects. The infants first viewed an object (an inverted white styrofoam cup decorated with stars, dots, and pushpins) standing on one of two placemats. A screen was then pushed in front of each placemat shielding the object from sight. After a 15-second interval, a hand wearing a silver glove and a bracelet of jingle bells reached behind one of the screens and emerged with the object. The infants were tested under two conditions. In the “possible event” condition, the object was retrieved from behind a screen that shielded the location where it had been seen hidden. In the “impossible event” condition, the object was retrieved from behind a screen that shielded a different location (see Fig. 1.1). Infants looked at the object longer in the impossible event condition.

Apparently, they were surprised to see that it had been retrieved from behind the screen that did not shield the original hiding place. Although many infants may not accurately search for an object, they can still remember where it was before it had been concealed. Their responses undermine Piaget’s position on object permanence—that infants’ lack of success on searching tasks is due to a conceptual limitation.

FIG. 1.1 The test events shown to 8-month-old infants (from Baillargeon & Graber, 1988).

Following the method used by Baillargeon, Wynn (1992) has attempted to demonstrate that infants possess rudimentary arithmetic abilities. Infants aged 5 months were shown toys placed successively behind a screen. When the screen dropped, either the number of toys that had been placed behind the screen appeared (the “possible outcome” condition) or there were more or less toys (the “impossible outcome” condition). Infants looked longer at the unscreened display when the outcome was impossible rather than possible. Wynn argues that infants have “true mathematical concepts” and that they are predisposed to interpret the physical world in terms of discrete objects that can be added or subtracted. If Wynn is correct, this would be a sensational result—demonstrating that human infants can add and subtract quantities such as 1 + 1 and 2 – 1. But, as Wynn herself notes, other interpretations exist. For example, infants may simply be demonstrating an ability to perceive continuous quantities in forming expectations about how much of a substance has been concealed.

The experiments of researchers such as Baillargeon and Wynn have shown how habituation techniques can be used as a method to communicate with infants. In general, the younger the child, the more likely an habitual or repeated presentation of the task will create disinterest. A long delay between concealing an object and the opportunity for retrieval may induce infants to fall back on an earlier hiding place where the object has been found on previous occasions (Diamond, 1985). A new and unexpected situation may recapture infants’ attention and permit a more genuine appraisal of their abilities.

Nevertheless, habituation techniques are not perfect measures of cognition in infancy. Although habituation seems an advance on research that relies on search patterns, it does not yield an unambiguous interpretation of how infants reason about objects (Carey, 1994). Even if infants look significantly longer at one display than another, this does not mean that they are contemplating the unexpected and are actually surprised. An improved measure of their understanding may demand a qualitative rather than a quantitative approach in which infants’ facial expressions are recorded as a more direct indication of surprise. Expressions such as surprise, sadness, anger, and happiness can be reliably scored (Ekman, 1994; Izard, 1994) and, as discussed next, the scoring of expressions has become the cornerstone of research on imitation in infancy.

IMITATION OF FACIAL EXPRESSIONS

An understanding of object relations may emerge from a capacity in newborns to learn through imitation. In a series of experiments reported in 1977, Meltzoff and Moore tested the proposition that infants between 12 and 21 days of age can imitate both facial and manual gestures. Six infants in a first experiment were shown the non-reactive, passive face of an experimenter for a 90-second period. Then four gestures were each repeated four times in a random order during a 15-second stimulus-presentation period immediately followed by a 20-second response period in which the experimenter resumed a passive face. The infants were observed to imitate the gestures of the experimenter: finger movements, opening of the mouth, and protrusion of the tongue and lips.

A second study was designed to rule out the possibility that interaction between the experimenter and infant might have resulted in a form of “pseudoimitation”: that is, the infants’ own random gestures might have altered those of the experimenter until their behaviour coincided with behaviour resembling imitation. Infants were shown the experimenter’s mouth opening and tongue protrusion gestures for 15 seconds while sucking attentively on a pacifier. They imitated the gestures when the pacifier was removed. In a similar manner, Tiffany Field and her colleagues (Field, Woodson, Greenberg, & Cohen, 1982) found that newborns imitated an experimenter’s happy, sad, and angry expressions. As Reissland (1988) has shown, such responses do not seem limited to white North American or European babies since babies born in rural Nepal also exhibit imitation of facial expressions. There may be something about the human face that elicits an imitative response, as in the first month of life infants will make a special effort to turn to look at a true depiction of a human face compared to a loose or scrambled configuration of facial features (Johnson, Dziurawiec, Ellis, & Morton, 1991)

Not all the data clearly indicates imitation in early infancy (see Lewis & Sullivan, 1985; McKenzie & Over, 1983). Yet there is now widespread agreement that babies can imitate by 6 months of age, long before Piaget’s estimate of between 8 months to a year. In fact, it can be speculated that a capacity for representation which may facilitate infants’ responses is present at birth. In a stud...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- 1 What Children Know Before Talking

- 2 Communication with Children on Number and Measurement Problems

- 3 Detecting Causality

- 4 Representing Objects and Viewpoints

- 5 Memory and Suggestibility

- 6 Understanding Persons

- 7 Authority and Academic Skills

- 8 Models of Knowledge

- References

- Author Index

- Subject Index