1

ANTI-SLAVERY AND WOMEN:

CHALLENGING THE OLD PICTURE

On 20 September 1840 anti-slavery campaigner Anne Knight wrote to her friend Lucy Townsend, who fifteen years before had founded the first women’s anti-slavery society in Britain. Anne called on Lucy to put herself forward for inclusion in the commemorative group portrait of the World Anti-Slavery Convention which had been held in London that June:

My dear long silent friend my slave benefactress Not now would I trouble thy retirement but I am very anxious that the historical picture now in hand of Haydon should not be performed without the chief lady of the history being there…in justice to history and posterity the person who established woman agency…has as much right to be there as Thomas Clarkson himself, nay perhaps more, his achievement was in the slave trade; thine was slavery itself the pervading movement the heart-stirring the still small voice….1

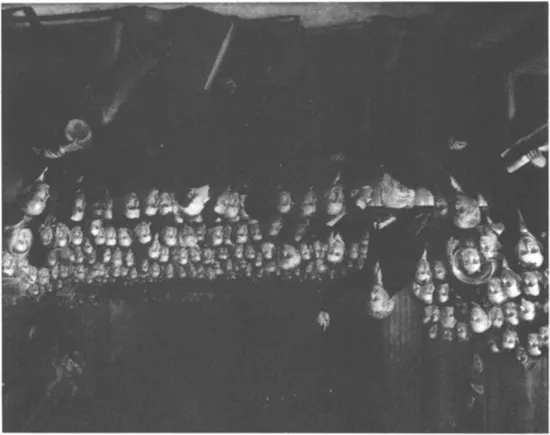

In the event Lucy Townsend was not included in the oil painting which Benjamin Robert Haydon produced, and I have been unable to locate any surviving image of the woman who initiated women’s anti-slavery organisations in Britain. Nevertheless Haydon’s group portrait (Figure 1) did include a number of women campaigners.2 The bonneted figure of Mary Clarkson, accorded a place on the platform by virtue of her relationship to Convention president Thomas Clarkson, is visible in the left foreground of the picture. Other women, confined to the visitor’s gallery, are mostly represented by Haydon as tiny unidentifiable figures in the background. However, because of his desire to make individual portraits of some of the women present, Haydon brought forward a group along the right-hand side of the picture, separated from the men by an almost invisible red barrier. In the key to the painting they are identified as follows: Mrs Tredgold and Mrs John Beaumont, the wives of two leading male activists; leading local women campaigners Mary Anne Rawson of Sheffield, Elizabeth Pease of Darlington and Anne Knight of Chelmsford; anti-slavery writer Amelia Opie of Norwich and aristocratic supporter Lady Noel Byron. A group of American women who had unsuccessfully attempted to gain admission to the Convention as delegates were not individually portrayed, with the exception of Lucretia Mott, whom Haydon accorded a tiny individual portrait in the background.3

Figure 1 The Great Meeting of Delegates, held at the Freemasons Tavern, June 1840, for the abolition of slavery and the slave trade throughout the world. Painting by Benjamin Robert Haydon, c. 1840.

Haydon’s group portrait is exceptional in that it does record the existence of women campaigners. Most other memorials did not. There are no public monuments to women activists to complement those to William Wilberforce, Thomas Clarkson and other male leaders of the movement. Commemorative medallions bear the images and names of the male leadership; even a medallion bearing the symbol of a kneeling enslaved woman (see Figure 10) adopted by ladies’ anti-slavery associations has on the reverse a list of male leaders and makes no mention of women activists. In the written memoirs of these men, women tend to appear as helpful and inspirational wives, mothers and daughters rather than as activists in their own right.

The nature of these memorials and memoirs provides one explanation as to why historians have not hitherto considered it necessary to explore female contributions in order to understand the British anti-slavery movement. Another factor has been the tendency to rely on the records and publications of the exclusively male national anti-slavery committees rather than on local provincial sources. Until recently it has been, quite simply, easy to ignore women anti-slavery activists.

More recently, as historians have increasingly acknowledged the essential part played by extra-Parliamentary activities and the pressure of public opinion in achieving abolition and emancipation, more attention has begun to be paid to women’s activities. Paradoxically, however, while the importance of local organisations to the success of the movement has been recognised, women’s contributions have continued to be devalued precisely because they were primarily community-based. The ladies’ anti-slavery associations set up from 1825 onwards have, quite wrongly, been dismissed as small in scale and as auxiliary to local men’s societies.4 In fact, as valuable preliminary studies by Louis and Rosamund Billington and by Karen Halbersleben have suggested, ladies’ anti-slavery associations were frequently large and autonomous organisations.5 This study will more clearly establish their vital importance to the anti-slavery network by exploring their national and local initiatives, their connections with each other, their development of distinctive female approaches to campaigning and their formulation of feminine perspectives on matters of anti-slavery policy and ideology.6

This book takes the women campaigners placed in the background and at the margins of other anti-slavery studies and places them in the foreground, at centre stage. In so doing it creates a counter-image to Haydon’s group portrait. The new picture presented here has emerged through two processes of research. The first process involved combing standard sources for anti-slavery history—memoirs of the national and Parliamentary leadership, and national society records, reports and periodicals—for information on women. The second process involved a comprehensive study of those neglected sources which specifically relate to women campaigners, many of them located in local rather than national libraries and archives: the large quantity of surviving records and published reports and pamphlets of local ladies’ anti-slavery associations; the anti-slavery pamphlets and imaginative works written by women, some published anonymously as befitted feminine modesty, but nevertheless attributable to particular women or at least to a female author; and memoirs and other sources of biographical information on women activists, in some cases privately printed by relatives.

Through piecing together information from such sources, it becomes clear that women, despite their exclusion from positions of formal power in the national anti-slavery movement in Britain, were an integral part of that movement and played distinctive and at times leading roles in the successive stages of the anti-slavery campaign. Furthermore, in putting women back into the picture many aspects of British anti-slavery history are clarified. For when historians ignore the activities of ladies’ anti-slavery associations, half the story of provincial anti-slavery organisation and of the generation of popular support for the movement on a nationwide basis is lost. And when historians dismiss women’s contributions as merely supportive of men’s, the fundamental ways in which gender divisions and roles structured the organisation, activities, ideology and policies of the movement as a whole go unnoticed. This study points out ways of rectifying these shortcomings through exploring both the sexual division of anti-slavery labour and the ‘gendered’ nature of anti-slavery politics.

A central preoccupation of anti-slavery historians since the work of Eric Williams in the 1940s has been to define the relationship between the rise of industrial capitalism and the growth of the anti-slavery movement.7 This study demonstrates that any satisfactory resolution of this question must take gender into account. David Brion Davis has delineated the role of anti-slavery in the establishment of middle-class ideological hegemony, while not losing sight of the sincere religious and intellectual beliefs which motivated campaigners.8 Here, it is demonstrated that anti-slavery ideas and motivations were as much related to issues of gender as to those of class, and that these issues interlocked. Anti-slavery ideology simultaneously raised and sought to suppress uncomfortable questions concerning the exploitation of women as well as the exploitation of labourers. Thus its relationship to feminism as well as to Chartism needs to be explored. Anti-slavery also drew on a spectrum of religious, intellectual and political perspectives and movements; the differing ways in which these influenced and affected men and women campaigners will be investigated.

The aim of this study is thus not to incorporate women into preexisting accounts of the anti-slavery movement. It is not to add to traditional anti-slavery hagiography a clutch of minor female ‘Saints’— the name given to William Wilberforce and other members of the evangelical Anglican ‘Clapham Sect’ of anti-slavery leaders. Rather, my aim is a disruptive as well as an informative one: to expose the need to rewrite existing general histories of anti-slavery, and to reconstruct the frameworks upon which they rest. The study of women campaigners of course forms only one part of this ongoing project: it is essential to a fuller understanding of the popular anti-slavery mobilisation which has been the subject of studies by James Walvin and Seymour Drescher.9 Following Robin Blackburn, I see this mobilisation as bringing about slave-trade abolition and slave emancipation through its complex interaction not only with Parliamentary politics, but also with social and economic changes in Britain and with slave resistance and revolt in the Caribbean.10 Indeed it should be stressed that the story told here, set in Britain, is only half the story of women and anti-slavery—the other half being the story, set in the West Indies, of the resistance of enslaved women themselves.11

As a whole, my study is inspired by the desire to realise the radical potential of women’s history through what Joan Scott has described as ‘the writing of narratives that focus on women’s experiences and analyse the ways in which politics construct gender and gender constructs politics’.12 The narrative presented here is intended both as an anti-slavery history and as a women’s history. It is as a political movement that anti-slavery has an especial importance to the history of women: it is not simply an example of female participation in public life, but more specifically of women’s involvement in one of the key mass movements for political reform of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. As such women’s anti-slavery campaigning cannot be neatly slotted into the framework of female philanthropy and charitable activity which has been delineated by historians as characterising women’s public work at this period.13 On the other hand, as will be shown, it is problematic to see their campaigning as a prelude to the women’s suffrage movement, that paradigm of early female political activity. Indeed one of the aims of this study is to illuminate the ambivalent and complex attitudes of women anti-slavery campaigners to their own social position: to their appropriate roles in the movement, and more widely to questions of women’s duties and their rights. This is an issue which has received far more attention in relation to campaigners for abolition and feminism in the United States than in Britain.14

Examining women’s participation in anti-slavery campaigns provides new insights not only into the history of feminism but more generally into gender roles in nineteenth-century British society, the focus of a recent major study of the English middle class by Leonore Davidoff and Catherine Hall.15 What emerges here is a complex picture in which women abolitionists were involved in constructing, reinforcing, utilising, negotiating, subverting or more rarely challenging the distinction between the private-domestic sphere and the public-political sphere which was so central to middle-class prescriptions concerning men’s and women’s proper roles in society. Indeed it becomes clear that women were not negotiating their role in the anti-slavery movement in relation to an established and fixed ‘public sphere’; rather, extra-Parliamentary political activities in support of anti-slavery were a key means by which both women and men developed the arena of civil society through the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.16

‘Separate spheres’ ideology had most impact on the lives of those activists who were the wives, mothers, daughters and sisters of middle- class men, middle-class themselves in terms of their lifestyles though rarely in terms of their independent economic position. It was these women who formed the bulk of activists in ladies’ anti-slavery associations. As will be shown, however, it would be a mistake to define anti-slavery as an exclusively middle-class movement. It also involved upper-class women and working-class women, and their differing political perspectives on and contributions to the movement, together with their relationships to the middle-class campaigners from whose organisations they were largely excluded, will also be explored. These white women together formed the bulk of female anti-slavery campaigners in Britain. However, there were also black women active against slavery in Britain. As will be shown, their actions challenged white women’s representation of enslaved women as silent and passive victims.

The overall picture of women campaigners which emerges in this book is structured around the key campaigning stages of the British anti-slavery movement. The first part of the book deals with women’s involvement in the campaign against slavery within Britain and against the British slave trade; the second examines their campaigning against British colonial slavery; and the third and final part discusses ‘universal abolition’ and especially women’s aid to North American abolitionists.