![]()

1 Pollution

What is pollution?

When a substance occurs in a location or organism at higher levels than normal, we say that the environment or body has been ‘contaminated’ by the substance. ‘Pollution’ is generally considered as an extension of this; it implies that environmental harm will, or might, be caused by the contamination. Furthermore, pollution is typically (although not always) associated with human activity; for example, significant quantities of polluting substances are lost to the environment during the extraction and processing of raw materials and the manufacture, use and disposal of final products. The major categories of anthropogenic pollutants are listed in Table 1.1.

Table 1.1 The main anthropogenic pollutants of concern.

Atmospheric pollutants |

Greenhouse gases: carbon dioxide, CO2; methane, CH4; nitrous oxide, N2O; ozone, O3 |

Oxides of nitrogen (NOX): nitric oxide, NO and nitrogen dioxide, NO2 |

Oxides of sulfur (SOX): sulfur dioxide, SO2 and sulfur trioxide, SO3 |

Stratospheric ozone depleting compounds: halogenated hydrocarbons (e.g. CFC); nitrous oxide, N2O |

Ammonia, NH3 |

Carbon monoxide, CO |

Volatile organic compounds, VOCs |

Particulate matter |

Freshwater and seawater pollutants |

Nutrients: nitrate and phosphate |

Acidifying substances |

Respirable organic matter |

Toxic trace elements |

Persistent organic pollutants |

Crude oil and petrochemicals |

Litter, including plastics |

Soil pollutants |

Nutrients: nitrate and phosphate |

Toxic trace elements |

Persistent organic pollutants |

Petrochemicals |

Radionuclides |

Natural pollutants

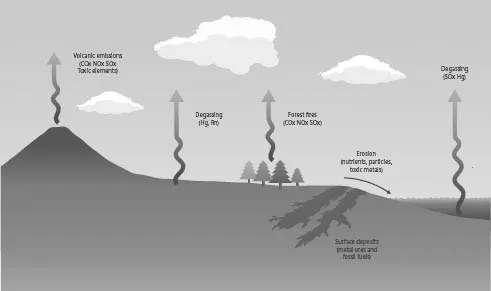

There are many natural forms of pollution (Fig. 1.1). The Earth’s crust is a major reservoir of most elements, some of them concentrated in relatively small volumes – in fossil fuel and metal sulfide deposits, for example. Over geological timescales, tectonic processes and erosion bring toxic elements, like arsenic and lead, and major elements, like carbon, to the surface environment where they can have adverse impacts. Elsewhere, volcanoes and natural forest fires emit gases and particles into the atmosphere. Some elements are emitted directly into the atmosphere from the Earth’s crust in gaseous form; for example, radon is a radioactive gas that is naturally emitted by granite and other rocks and can cause lung cancer if inhaled over a period of time. Mercury vapour also diffuses into the atmosphere from the Earth’s crust. Some naturally occurring organic compounds are very toxic. An example of natural ‘pollution’, from an early period of Earth history, is that of the ‘great oxygenation event’ (GOE) of some 2.5 billion years ago, when oxygen first accumulated in the atmosphere as a result of the evolution of photosynthesising cyanobacteria in the oceans. Oxygen is toxic to anaerobic organisms, which must have declined significantly at this time; they persist today in oxygen-free environments such as lake-bottom sediments and animal intestines. The GOE also illustrates that some substances that we might not think of as toxic can be very harmful to some organisms.

Figure 1.1 Examples of natural sources of pollution. This diagram is simplified for clarity and the element chapters should be consulted for full details of natural processes. For example, several sulfur-containing gases (not shown) are emitted into the atmosphere from the oceans, but these ultimately oxidise to SOx, which is shown on the diagram (right).

Anthropogenic pollution: past, present and future

The earliest forms of anthropogenic pollution are likely to date back far into prehistory, occurring in settlements where sewage and drinking water were not adequately separated. Pollution of the air probably has a long history too, arguably dating back to the earliest use of fire. A much later milestone is likely to have been the development of metal working in ancient times, when primitive extraction and smelting techniques could conceivably have caused localised problems of poor air quality and possibly water pollution. The earliest laws against pollution were most likely passed for the protection of water quality, in Roman times for example, and in medieval times a ban was placed on the burning of poor quality coal in London. In the 18th century, polluting activities escalated dramatically at the onset of the Industrial Revolution and, in the current era, gross pollution from heavy industry continues in many parts of the world, most especially in the ‘newly industrialised nations’ such as China and India. In comparison, many of the former industrial powerhouses of Europe, America and elsewhere are now ‘post-industrial’ economies with less heavy industry. Despite this, pollution problems persist in such countries, both from the legacy of past industrial activities (especially in contaminated soils and sediments) and from present-day activities such as food production, power generation, waste management, transportation and remaining industries.

Looking ahead, pollution problems are likely to persist and potentially increase in magnitude in the future, despite progress on regulatory, technologically and economically-driven pollution control measures. A rapidly increasing world population and, more particularly, global per-capita increases in resource exploitation and material consumption mean that environmental pollution will remain a significant concern for the foreseeable future, with continuing risks to human health and vulnerable ecosystems.

Sources and receptors

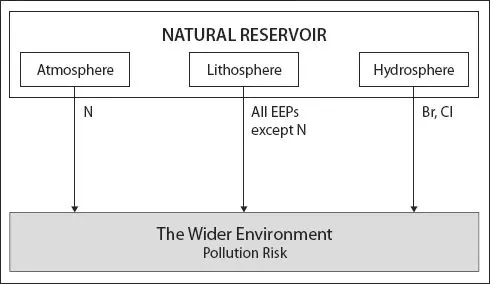

Pollution arises chiefly from the human disturbance of natural elemental cycles and the transfer of elements and their compounds to parts of the physical environment where they would normally be found at lower concentrations or, in some cases, not at all. In most cases this entails the release of elements from the Earth’s crust by extraction of minerals and fossil fuels (and their processing and/or combustion), followed by the utilisation of these raw materials in the manufacture of material goods or the provision of power. However, there are exceptions; for example, in the manufacture of nitrogenous fertilisers, N is transferred from the atmosphere to the Earth’s surface {→N} and Br (and some Cl) is derived from the sea {→Br →Cl} (Fig. 1.2). Deliberate, accidental or negligent releases of process wastes to the environment during processing and final product use can cause pollution. End-of-life product disposal (e.g. landfill and waste incineration) creates other pollution hazards. Major pollution sources are shown in Table 1.2, along with primary physical ‘receptors’, i.e. the components of the physical environment (air, soils, waters) that are typically the initial recipients of the different pollution types. Of course, receptors of pollution also include the humans, animals, plants and other organisms that inhabit these environments (see Pathways section, below).

Figure 1.2 Most of the ‘elements of environmental pollution’ (EEPs) are extracted from the Earth’s crust (the lithosphere) and transferred into the air, waters and soils; however, Br, Cl and N are notable exceptions.

Table 1.2 indicates that most pollution problems can be attributed to just a few broad categories of human activity: agriculture, manufacturing industry, transportation, power generation and waste management. These activities are described briefly below, together with indications of where more detailed discussions appear in the appropriate element chapters.

Agriculture

Modern agriculture is highly dependent on the use of pesticides and fertilisers to minimise crop damage and target maximum yield (Fig. 1.3). Pollution occurs when these chemicals (and manures) are washed off, or through, soils into surface waters and groundwaters. Fertiliser pollution causes eutrophication and other impacts {→N →P}, while pesticides can be directly toxic to humans and wildlife {→C →Cl →P}. Another pollution impact arises from the burning of biomass, including forested areas, in order to clear land for agricultural use; impac...