![]()

| I | Encounters with Number and First Acquisitions |

![]()

| 1 | Learning about Numbers Lessons for Mathematics Education from Preschool Number Development |

Catherine Sophian

University of Hawaii

An important issue both for cognitive-developmental theory and for educational practice concerns the relationship between the development of mathematical concepts and the acquisition of numerical procedures. In developmental work, discussion of this issue has focused on the relationship between counting and the development of mathematical concepts, particularly cardinality. Piaget (1941/1952a) viewed these two developments as quite independent. Because he was mainly interested in conceptual development, he had little to say about children’s counting, but the attention he did give it was merely to make the point that counting does not play an important role in the development of conceptual knowledge about number. Recent research, in contrast, has put a lot of emphasis on children’s counting, taking it both as an indication of the richness of even very young children’s mathematical knowledge (Gelman & Gallistel, 1978) and also as a potentially important factor in the development of conceptual knowledge about number (Gelman, 1982a; Klahr, 1984b).

An important ramification of the research on counting has been to emphasize that it is as much a theoretical problem to account for the development of counting as to account for the development of numerical concepts like cardinality. In characterizing counting as merely “verbal,” Piaget suggested that it fell outside the bounds of the conceptual development that he was interested in explaining. It seems incompatible with his general theoretical position, however, to view it as wholly independent of children’s conceptual development. Whereas Piaget allowed for figurative aspects of development, he always viewed them as subordinate to operative development. An integrated account of conceptual development and the development of counting seems all the more critical insofar as we accept the characterization of counting as based on principles that represent substantial, albeit implicit, knowledge about number (Gelman & Gallistel, 1978; Gelman & Meck, 1983). At the same time, however, this characterization presents a challenge to Piaget’s account of conceptual development, because he did not believe that children achieve a conceptual understanding of number until the concrete-operational period of development, several years after they have learned to count.

Questions concerning the relationship between procedural and conceptual aspects of mathematical development are as important practically as they are theoretically. Accumulating evidence of conceptual deficits in children’s mathematics learning has led educators to recognize that schools must teach more than computation. There is little satisfaction in having taught children how to perform calculations when they are unable to use those procedures to solve any but the most routine problems (Cockcroft, 1982; National Assessment of Educational Progress, 1983), and even purely computational errors often reflect inadequate conceptual understanding (Resnick, 1984). At the same time, most educators seem to agree that children need to learn computational skills as well as concepts (Hughes, 1986; Resnick, 1989; Resnick & Ford, 1981); the question they face is how best to combine the two. Should schools teach the concepts first, and then the procedures that build on those concepts? Or is it better for children to begin with the procedures and then reflect on what they are doing once they are able to do it? Clearly, developmental questions about the causal relationships between procedural and conceptual knowledge have important ramifications for these educational issues.

In this chapter I begin by reviewing a series of studies I have conducted on preschool children’s knowledge about counting and cardinality, and then present a theory of number development that accounts for the findings. I conclude by discussing the implications of my theoretical position for early mathematics education. Although the content of school mathematics is clearly different from the early numerical developments that I have studied in my research with preschool children, the parallel issues concerning procedural and conceptual knowledge in the two domains provide a basis for drawing instructional conclusions from the developmental research.

It should be noted that different definitions of cardinality, and different methods for studying it, have been used in different lines of research. Piaget’s original work was based on the classical mathematical definition of cardinality in terms of one-to-one correspondence: Two sets have the same cardinal number if and only if their elements can be put into one-to-one correspondence. Piaget combined this definition with his theoretical interest in transformations in his research on conservation: He did not credit children with understanding cardinality until they knew that the equivalence between two sets is unchanged when the perceptual alignment between them is destroyed by spreading out or condensing one of the sets. In the portion of my own research that I discuss here, I maintain a focus on correspondences between sets but not the emphasis on transformations that characterized Piaget’s work. Instead, I focus on children’s ability to use counting or single number words to reason about equivalences between sets that are never presented in a perceptually aligned way. A useful feature of this approach is that it can be examined both in relation to counting and in relation to children’s understanding of numbers as they are used in natural language.

In research on children’s counting, cardinality has also been inferred from children’s behavior in relation to just a single set (e.g., Fuson & Hall, 1983; Gelman & Gallistel, 1978; Schaeffer, Eggleston, & Scott, 1974). Certainly it is an important achievement for children to realize that when they count a single set, the last number in their count represents the numerosity of the whole set, although it may not necessarily follow that they can use that representation to reason about its relationship to other sets (Sophian, 1987). Although I do not discuss research on this aspect of cardinality in any detail here, I do take it into account when I discuss theoretical ideas about the relationship between counting and cardinality.

The Development of Cardinal Aspects of Counting

In several studies, I have examined young children’s understanding of counting as a source of numerical information that can be used to reason about relationships between two sets. These studies address the question of the relationship between counting and cardinality by investigating the development of cardinal aspects of children’s counting. If a concept of cardinality precedes children’s counting and guides them as they learn to count, then cardinality should be an integral part of children’s counting from the earliest phases of its development. On the other hand, the conclusion that cardinal aspects of counting are a relatively late achievement in the development of counting would imply that counting is not initially learned as a cardinal activity but only gradually becomes integrated into children’s developing understanding of cardinality.

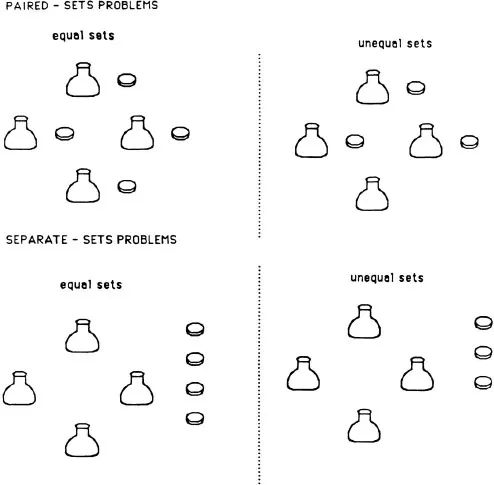

Experiment 1: Counting to Compare Two Sets

In the first study I conducted on this issue (Sophian, 1987, Experiment 1), I asked 3-year-old children questions about the relationship between two sets that were presented either in a pairwise fashion or in different spatial configurations (see Fig. 1.1). The sets contained between three and seven objects, and the pairs of sets were either equal in number or differed by one. Children were not asked to count the objects; they were simply asked about the correspondence relation between the two sets, for example, “Are there enough lids so that every jar can have a lid?”. (There were never more lids than jars.) Of course, when the sets were paired, children did not need to count in order to answer the question. I included these trials in order to make sure that the children understood the questions I was asking. On the separate-sets trials, counting was a potentially useful way of comparing the two sets. The results are summarized in Table 1.1. Children did show a good understanding of the comparison questions, in that they performed well on the paired-set problems. As expected, it was more difficult for them to compare the sets without counting on the separate-sets trials; nevertheless, they seldom counted on those trials, although counting was somewhat more prevalent among the older children.

Fig. 1.1. Types of arrays used in Experiment 1.

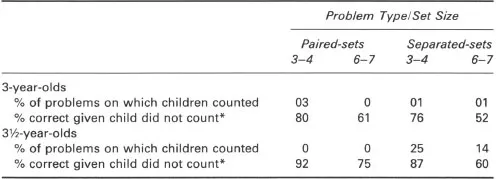

Table 1.1

Patterns of Performance on Paired-Sets and Separated-Sets Problems (Experiment 1)

* Chance = 50%.

To ascertain that the problem was not just lack of counting skill, I asked the children explicitly to count single sets of the same sizes on a posttest. Although some children did have very limited counting skills (eight of eighteen 3-year-olds and four of eighteen 3½-year-olds failed to count sets of four or more items correctly), many others were able to count at least the smaller set sizes accurately on the posttest and yet did not even once attempt to count on the comparison problems (nine 3-year-olds and eight 3½-year-olds fit this pattern).

Interestingly, even when children did count on the separate-sets comparison problems, they were not very likely to arrive at a correct answer to the question. While this may be due in part to errors in children’s counting, it is also at least in part a reflection of their lack of understanding of how to use counting to solve the problems. On several trials, children counted only one of the two sets; and on others they counted both sets yet subsequently gave an answer that did not correspond to the results of their counting. Similar observations have been made in other studies of children’s use of counting to compare two sets (Saxe, 1977).

Experiment 2: Counting to Generate Equivalent Sets

In a second study (Sophian, 1987, Experiment 2), I asked children to construct a second set that had the same number of objects as a set I presented. As in the previous study, I used sets that contained three to seven objects, and I asked children either to put the new objects in a separate grouping and a different spatial configuration than the original set or to put them with the original set. The children in this study were 3½-year-olds (comparable to the older group in the previous experiment), 4-year-olds, and 4½-year-olds. The results, which are presented in Table 1.2, were similar to those of the first experiment. On the separate-sets trials, where children could not use a simple pairing strategy, 3½-year-olds seldom counted either set whereas the 4½-year-olds often counted. Yet children at all ages did show a good understanding of what they were asked to do, performing well on the paired-set problems.

Table 1.2

Patterns of Performance on Paired-Sets and Separated-Sets Problems (Experiment 2)

Experiment 3: Judgments About Counting to Compare Two Sets

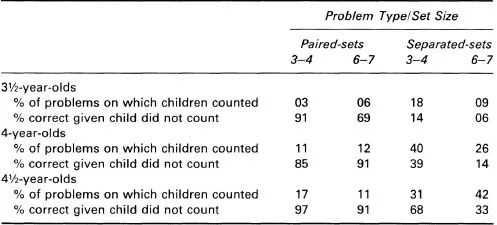

A third study examined children’s understanding of counting as a way of comparing two sets when they did not have to do the counting themselves (Sophian, 1988). In this study, 3- and 4-year-old children observed a puppet who was asked about a set of objects comprised of two subsets (e.g., on some trials there would be three baby horses and three big horses). The puppet was asked either about the total number of objects (“how many?” task) or about the relationship between the two subsets (compare task). In both cases the puppet responded sometimes by counting all of the objects together (e.g., “one, two, three, four, five, six”) and sometimes by counting the two subsets separately (e.g., “one, two, three, three baby horses; one, two, three, three big horses”). Before the puppet had a chance to draw any conclusion from his counting, the child was asked to judge whether or not the way the puppet had counted was a good way to find out the answer to the question he had been asked. (Warm-up trials with non-numerical problems were used to familiarize children with this judgment task.)

The results are summarized in Fig. 1.2. Both age groups performed better on the how-many task than on the compare task, but the specific patterns of performance that they showed differed. The 3-year-olds tended to judge both types of counting as good regardless of the puppet’s task, but in the “how-many?” task they judged counting of all the objects together as good more often than counting of the two subsets separately; the 4-year-olds, by contrast, were much less likely than the 3-year-olds to say that the puppet had counted properly when he counted the two sets separately—even on the compare task. Thus, like the 3-year-olds, on the “how-many?” task they appropriately judged counting of all the objects together as good more often than counting of the two subsets separately; however, they showed the same pattern on the compare task, where it was not appropriate.

Fig. 1.2. Mean proportions of puppet’s counts that were judged “good” in Experiment 3.

These findings indicate that the limitations on children’s use of counting are not just a production problem. Children show the same limitations in their understanding of counting as a way of comparing two sets whether they are doing the counting themselves or evaluating counting that they have observed.

Experiment 4: Inferring the Numerosity of a Corresponding Set

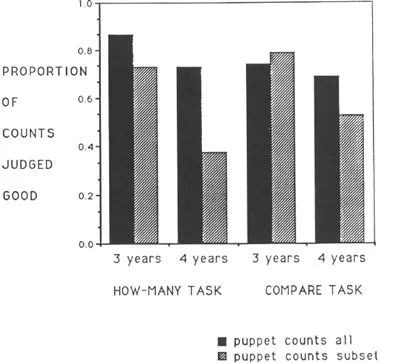

Finally, (Sophian, 1989) I examined children’s ability to make inferences about the number of objects in a set that was presented in one-to-one correspondence with another set that they were instructed to count (Sophian, 1989). In this study the question was not whether children would count spontaneously, but rather whether they could use the results of a count to reason about two sets that were in one-to-one correspondence with each other.

To establish the correspondence between the sets, the experimenter presented objects in pairs (e.g., trucks and elephants, nests and birds). She put one member of each pair (e.g., the trucks) on the table in front of the child and the other member (e.g., the elephants) into a box. After she had presented all the objects, she asked the child to count the set that was on the table, and then asked how many objects were in the set in the box (where they were out of sight). (For methodological reasons, on half the trials she added an extra object to the box before having the child count; for present purposes, however, let us consider just the data from the same-number trials, which provide a simpler test of children’s understanding of the cardinal significance of their counting.)

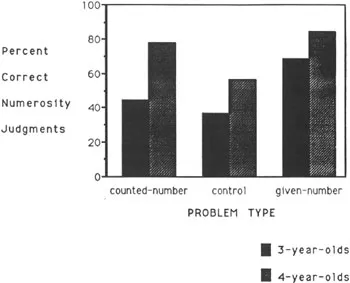

The accuracy of numerical responses the children made on these trials, and on corresponding control trials on which the children did not have the opportunity to count the set on the table, are summarized in the left and middle sections of Fig. 1.3. As in the other studies I have described, the 3-year-olds were less successful in using counting to reason about corresponding sets than were the 4-year-olds. Their performance on the trials on which they had counted was not significantly better than on the control trials. The 4-year-olds’ performance, in contrast, was significantly better on the count trials than on the control trials.

Fig. 1.3. Mean proportions of problems on which children made correct numerosity judgments in Experiment 4.

Cardinal Aspects of Early Counting: Conclusions

In sum, the consistent finding across these studies is that 3-year-old children do not connect counting with problems concerning the numerical relationship between two sets. They do not spontaneously count to compare two sets or to construct equivalent sets; they cannot distinguish between appropriate and inappropriate forms of counting for comparing two sets; and they do not use the information they obtain by counting one set to infer the number of objects in a second set that is in one-to-one correspondence with that set. By 4½ years of age, performance is much better on all of these problems. These results suggest that cardinality, at least that aspect of cardinality that has to do with the relationships between two sets, is a relatively late achievement in the development of children’s counting.

The Cardinality of Counted and Noncounted Numbers

Although coun...