1 The function–structure model of attitudes

Incorporating the need for affect

Gregory R. Maio, Victoria M. Esses, Karin H. Arnold and James M. Olson

Introduction

Why do I like the Toronto Maple Leafs so much? This question occurs often to the first author and many other fans of this ice hockey team, especially during losing streaks. No doubt similar questions occur to millions of sport fans worldwide, all of whom spend abundant time and money watching a collection of grown men or women kick, throw, or shoot a spheroidal object across a delineated terrain under a complex system of rules. It could be suggested that fans’ favorability toward their teams arises because of their beliefs, feelings, and past experiences regarding the teams. People may like particular sports teams because the teams’ players appear to have good personal and athletic attributes, the teams make us feel good, and people may have many fond memories of seeing the team perform live on outings with mom or dad.

This explanation is difficult to reconcile, however, with observations that some teams consist of disreputable characters who have no history with the region for which they play, some teams retain a high fan base despite losing with torrid frequency (e.g., the Toronto Maple Leafs in the 1980s), and many “bandwagon” fans have little or no prior experiences with the teams. It may not be possible to explain fans’ positive attitudes toward their teams simply by looking at their beliefs, feelings, and past behaviors regarding the teams; other factors must moderate the effects of these attitude components.

The present chapter proposes that, in general, the effects of beliefs, feelings, and past behaviors on attitudes depend on salient motivational goals. We begin by outlining a model of attitudes that explicitly considers the motivations that guide attitudes, in addition to the beliefs, feelings, and behaviors that influence attitudes. We then focus on one new motivation that may play an important role in attitude formation and change: the need for affect.

The function–structure model

According to the three-component model of attitudes (see Zanna & Rempel, 1988), attitudes express beliefs, feelings, and past behaviors regarding the attitude object. For example, a young man might have a positive evaluation of a colorful polyester Hawaiian shirt because he believes that the shirt looks good on him (cognitive component) and the shirt reminds him of fun times in the tropics (emotional component). In addition, through self-perception processes (Bem, 1972; Olson, 1990, 1992), he might decide that he must like the shirt because he can recall that his coworkers had no trouble convincing him that he should wear a similar shirt to important business functions (behavioral component). On the basis of these beliefs, feelings, and past behaviors, he might form a general positive attitude toward the conspicuous item. In general, people who have positive attitudes toward an attitude object should often possess beliefs, feelings, and behaviors that are favorable toward the object, whereas people have negative attitudes toward an attitude object should often possess beliefs, feelings, and behaviors that express unfavorability toward the object (see Eagly & Chaiken, 1993).

Nonetheless, people’s beliefs, feelings, and behavior toward an object can sometimes differ in their valence and, therefore, in their implications for their overall attitude. For example, the young man in our example may feel uncomfortable in the polyester fabric of the vivid Hawaiian shirt, despite his other positive beliefs and emotions. Research on the valence of people’s attitude-relevant beliefs, feelings, and behaviors has provided evidence that they are empirically distinct. For instance, some researchers have asked participants to list their beliefs, emotions, and behaviors regarding an attitude object and to rate the valence of each response (Esses & Maio, 2002; Haddock & Zanna, 1998). Results have generally indicated low to moderate correlations between the components of attitudes toward a large variety of issues, objects, and behaviors (e.g., birth control, blood donation, microwaves; Breckler & Wiggins, 1989; Crites, Fabrigar, & Petty, 1994; Esses & Maio, 2002; Haddock & Zanna, 1998; Trafimow & Sheeran, 1998). Consistent with these low relations, attitude-relevant feelings and beliefs are also clustered separately in memory (Trafimow & Sheeran, 1998).

Researchers have found that some attitudes are uniquely related to feelings about the attitude object, whereas other attitudes are uniquely related to beliefs about the attitude object. For example, feelings are particularly strong predictors of attitudes toward blood donation (Breckler & Wiggins, 1989), intellectual pursuits (e.g., literature, math; Crites et al., 1994), smoking (Trafimow & Sheeran, 1998), condom use (de Wit, Victoir, & Van den Bergh, 1997), deaf people (Kiger, 1997), politicians (see Glaser & Salovey, 1998, for a review), and alcohol and marijuana use in frequent users of these drugs (Simons & Carey, 1998). In contrast, beliefs are strong predictors of reactions to persuasive messages (Breckler & Wiggins, 1991) and attitudes toward a variety of controversial issues (e.g., capital punishment, legalized abortion, nuclear weapons; Breckler & Wiggins, 1989; Crites et al., 1994). All of these unique relations support the distinction between the cognitive and affective components of attitudes. No prior theory, however, predicts when one component will more strongly influence attitudes than the other components. This issue is important because the relative predictive power of different components can vary, even for similar attitude objects. For example, although researchers have found that affect is a stronger predictor than cognition of attitudes toward most minority groups (Esses, Haddock, & Zanna, 1993; Haddock, Zanna, & Esses, 1993; Jackson, Hodge, Gerard, Ingram, Ervin, & Sheppard, 1996; Kiger, 1997; Stangor, Sullivan, & Ford, 1991), cognition can also be a stronger predictor than affect of attitudes toward some minority groups (Esses et al., 1993). In general, the relative weighting of these sources of information can vary across individuals and attitude objects (e.g., Eagly, Mladinic, & Otto, 1994; Esses et al., 1993; Haddock et al., 1993; Haddock & Huskinson, Chapter 2 this volume; Trafimow & Sheeran, Chapter 3 this volume).

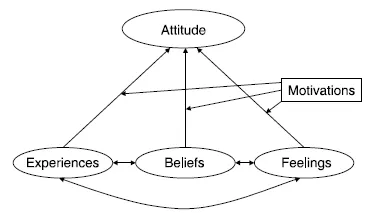

We propose that motivational goals exert a fundamental influence on the dominance of particular attitude components. We have previously labeled this conceptualization the function–structure model of attitudes (FSM; Maio & Olson, 2000a). As shown in Figure 1.1, this model proposes that salient motivations influence the weighting of information within each attitude component. Certain goals might be salient because they are chronically or temporarily accessible for some individuals. For example, the attitude object may be associated in memory with a particular motive (e.g., Shavitt, 1990), causing the motive to be chronically accessible when the object is present. Alternatively, temporary features of the immediate situation may be associated in memory with a particular motive (e.g., Young, Thomsen, Borgida, Sullivan, & Aldrich, 1991). For instance, the presence of credit card logos or money might activate utilitarian motivations to pursue wealth, and this motive might be particularly strong in a person who is surrounded by others wearing expensive clothing.

The effect of the salient goals on the weighting of each component should depend on the extent to which the components contain information that is particularly relevant to the goals. Consider again our Hawaiian shirt example. If the man who is thinking about the shirt is experiencing a need to impress others, then his belief that the shirt suits him should have a large impact on his current attitude. In contrast, if he has stronger pecuniary concerns, his belief that the shirt was inexpensive should be weighted most heavily. Alternatively, if he is experiencing a strong need to feel comfortable and relaxed, then his attitude should be influenced heavily by the discomfort evoked by the polyester fabric. In sum, salient motivations should affect the weights assigned to various beliefs, feelings, and past experiences, and these components should, in turn, affect the current overall attitude to the object.

Figure 1.1 The function–structure model of attitudes: motivations moderate the effects of beliefs, feelings, and experiences on attitudes.

What are the types of motivation that may be influential? Seminal theories of attitude function (Katz, 1960; Smith, Bruner, & White, 1956) provide some clues about potentially influential motivations. Smith et al. (1956) suggested that attitudes can serve object-appraisal, social-adjustment, and/or externalization functions. The object-appraisal function encompasses the ability of attitudes to summarize the positive and negative characteristics of objects in our environment. In other words, attitudes enable people to approach things that are beneficial for them and avoid things that are harmful to them. The social-adjustment function is served by attitudes that help us identify with well-regarded individuals and dissociate from disliked individuals. For example, people often like and purchase styles of clothing that are worn by celebrities. The externalization function is served by attitudes that defend the self against internal conflict. For instance, a poor squash player might grow to dislike the game because it threatens his or her self-esteem.

In a separate program of research, Katz (1960) proposed that attitudes may serve knowledge and utilitarian functions, which are similar to Smith et al.’s (1956) object-appraisal function. Specifically, the knowledge function reflects the ability of attitudes to summarize information about objects in the environment, and the utilitarian function exists in attitudes that maximize rewards and minimize punishments obtained from objects in the environment. Katz also proposed that attitudes may serve an ego-defensive function. This function is similar to Smith et al.’s externalization function, because both functions involve protecting self-esteem. Finally, Katz suggested the existence of a value-expressive function, which exists in attitudes that express the self-concept and central values (Rokeach, 1973; Schwartz, 1992). For example, some people favor cycling to work because they value health.

It is possible, however, to distinguish between motives that are fulfilled by particular attitude positions versus motives that are fulfilled by holding attitudes per se. This point is illustrated by Smith et al.’s (1956, p. 41) description of the object-appraisal attitude function:

Attitudes aid us in classifying for action the objects of the environment, and they make appropriate response tendencies available for coping with these objects. This feature is a basis for holding attitudes in general as well as any particular array of attitudes. In it lies the function served by holding attitudes per se.

This description emphasizes that all strong attitudes simplify interaction with the environment, regardless of whether the attitudes are negative or positive. For example, people who definitely like or dislike MG sports cars should have less difficulty deciding whether to purchase one of these vehicles than people who have no strong prior attitude toward them. In contrast, other attitude functions explain why people form a negative versus positive attitude. For example, the social-adjustive function explains why people like clothing that is popular, whereas they dislike clothing that is unpopular. That is, the negativity or positivity of attitudes toward clothing depends on whether the clothing fulfils social-adjustive concerns.

These seminal models of attitude function do not provide a comprehensive list of functions, however, because they propose overlapping functions and neglect other important functions (Maio & Olson, 2000a). The overlap is shown by the fact that the value-expressive function can encompass utilitarian motives, because contemporary models of values recognize that social values can serve many goals, some of which are utilitarian in nature (e.g., achievement, enjoying life; Schwartz, 1992). Moreover, persuasive messages that target different utilitarian values have different effects on participants’ subsequent attitudes (Maio & Olson, 2000b). Consequently, the existing classes of attitude function can be further subdivided. Furthermore, research in and outside of the social psychology literature has identified motivations that are not considered at all in current models of attitude function, such as a need for consistency (Cialdini, Trost, & Newsom, 1995) and the need for dominance (Murray, 1938, 1951).

Rather than use a limited taxonomy of motivations, the FSM is open to a wide range of motivations, which may be reflected in prior taxonomies of human motivations (e.g., Murray, 1938) and values (e.g., Schwartz, 1992). Motivations for forming attitudes in general have been particularly neglected in past theorizing. Smith et al.’s (1956) object-appraisal function (which subsumes the knowledge and utilitarian functions described by Katz), has been the only motivation that has been theoretically and empirically linked to the formation of attitudes per se (Eagly & Chaiken, 1993; Herek, 1986; Olson & Zanna, 1993; see also Katz’s, 1960 knowledge function). The importance of the object-appraisal motive is supported by data showing that people respond faster to attitude objects for which they have highly accessible (i.e., easy to retrieve) attitudes (Fazio, 1995, 2000). These data support the notion that attitudes facilitate responding to attitude objects, at least when the attitudes themselves are accessible. Participants are also more likely to form or maintain attitudes in situations that elicit a high need for closure than a low need for closure (Kruglanski, Webster, & Klem, 1993; Thompson, Kruglanski, & Spiegel, 2000). This finding is consistent with the role of the object-appraisal motivation, because the need for closure is a need for “a definite answer on some topic, any answer as opposed to confusion and ambiguity” (Kruglanski, 1989, p. 14). Attitudes are capable of providing such “answers.” Therefore, they should be formed and protected when people make decisions about attitude objects.

The object-appraisal function does not provide a complete account of the motives served by attitude formation, however. This function explains how attitudes simplify the cognitive processing of attitude objects, but it does not completely explain the intensity of people’s affective reactions to attitude objects. In theory, attitudes could direct people’s thoughts and behaviors in a manner that is devoid of feeling. For example, when people try to decide whether they should vote for a specific politician, they could simply recall an abstract, emotionless evaluation indicating varying degrees of unfavorability or favorability toward the politician. This recalled evaluation could direct their vote without the elicitation of strong negative or positive feelings. Attitudes are accompanied by affective reactions, however (e.g., Cacioppo & Petty, 1979; Dijker, Kok, & Koomen, 1996; see also Olson & Fazio, 2001), and the psychological function of these reactions should be addressed.

The FSM proposes that there is an additional motive that can help explain attitude formation. Specifically, people may have a built-in need to experience emotions, and attitudes can help fulfil this need. This hypothesis is partly based on Zajonc’s (1980) proposal that the experience of affect is a basic process and that affective reactions give meaning to the world around us. Affect serves many functions, such as keeping us aroused, helping us communicate with others, and providing motivational impetus to our behavior. Affect may even elicit its own unique system for information processing (Epstein, 1998). Consequently, the experience of emotions may be intrinsically satisfying (Maio & Esses, 2001), and people may form attitudes as a means of experiencing and expressing emotions.

In addition, however, people’s attitude positions may be influenced by individual differences in and situational determinants of their need for cognitive simplicity and their need for affect. For example, people may adopt attitude positions that enable them to maintain the simplest perspective (Webster & Krugklanski, 1994). If a message presents simple information in favor of one point of view (e.g., favorable to censorship) and complex information in favor of an alternate point of view (e.g., unfavorable to censorship), people who are experiencing a need for cognitive simplicity might be more likely to adopt the attitude associated with the simple information.

Similarly, because people who are high in the need for affect should seek and enjoy affective stimulation, their attitude positions might be influenced more strongly by affective information (e.g., taste of a product) than by more cognitive, factual information (e.g., nutritional value of a product). Among people who are high in the need for affect, attitudes toward an object might be more favorable if a message describing the object is accompanied by positive affective stimuli (e.g., attractive models) than if the message contains positive information but no emotional value.

In sum, the FSM proposes that attitude positions are influenced by beliefs, feelings, and past experiences regarding the attitude object, and that the impact of these attitude components depends on salient motivations. In addition, the model proposes that the formation of attitudes in general fulfills a need for cognitive simplicity and a need for affect, which may also influence attitudinal positions. To date, ...