- 336 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The highway has become the buyway. Along the millions of miles the public travels, advertisers spend billions on images of cola, cars, vodka, fast food, and swimming pools that blur past us, catching our fleeting attention and turning the landscape into a corridor of commerce. A smart, succinct, and visually compelling history of the billboard in America, Buyways traces how the outdoor advertising industry changed the face of American commercialism. Taking us from itinerant bill-stickers of circus posters in the 19th century to the blinking, beeping, 3-D eyesores of today, Gudis argues that roadside advertising has turned the landscape itself into a commodity to be bought and sold as advertising space. Buyways vividly chronicles the battles between environmentalists and businessmen as well as the response of artists, from New Deal photographers who satirized the billboard-infested landscape to commercial artists who embraced the kitsch of it all. It also shows how advertisers tapped into the American mythology of the open road, promoting mobile consumption as the American Dream on four wheels. Entertaining and brilliantly illustrated, Buyways is a vibrant road map of the new geography of consumption. Also includes an eight page color insert.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Buyways by Catherine Gudis in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1: BEFORE THE CAR

As industrial America grew, so did advertising outdoors. Handbills and broadsides for farm machinery, auctions, runaway slaves, stagecoach schedules, and theatrical performances had long fluttered on the walls outside inns and taverns. By the time of the Civil War, banners and posters for circuses and other celebrations comprised a good portion of the finery draping city buildings, past which might rattle a flamboyantly decorated advertising wagon. Painted patent medicine ads screeched their messages from rocks, trees, and fences. Gaslit signs illuminated blocks of New York City. To the titillation of many, sandwich men paced the streets with signs hung over their shoulders and display cases, hats, or other objects perched upon their heads.1 “Never a brick pile rises in any part of the city,” someone noticed in 1867, “but it is covered almost in a night with the fungus and mould of hot notoriety-hunting.”2 Growing cities became embroidered with the handiwork of the billposter and his minions, whose overlapping, multilayered mixed messages offered ephemeral companionship to the brick and mortar of rising buildings. These ads served as an apt symbol for burgeoning commercial culture as well as for the constant change and instability characteristic of the rapidly expanding and increasingly heterogeneous metropolis.3

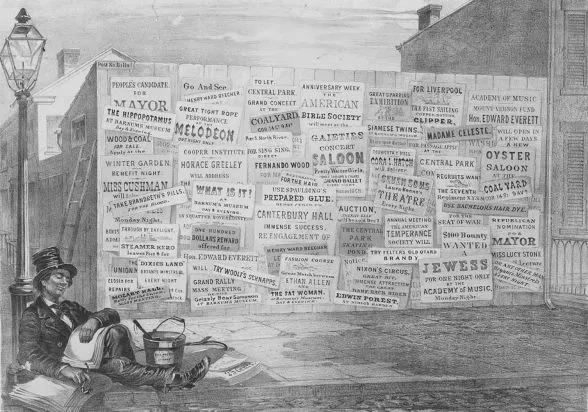

New York journalist George Foster, in his popular 1850 account New York by Gas-light, was among those who commented on the mutability of the messages that plastered the city, which served less as a testament to the poetry of advertisers than to the battles between billposters. On the “calicoed surface” of the Park Theater, for instance, one could read “interminably from the handbills lying like scales . . . one upon another” something that went like this: “‘Steamer Ali—Sugar-Coat—and Pantaloons for—the Great Anaconda—Whig Nominations—Panorama of Principles—Democrats Rally to the—American Museum’—and so on.”4 Any one message was lost in the cacophony (fig. 2). The well-coated wall was the result of billposters’ efforts to lighten their loads of paper and to beat their competitors at the same game.

The billposters’ ad-hoc practices and competing claims to space meant that no available surface was sacred, and even a wall freshly papered with bills seemed to beg to be anointed by the next fellow’s paste brush. Even the Memorial Presbyterian Church in New York was forced to publish a special newspaper notice admonishing the billposter who insisted upon covering the church’s own posters for their fair.5 The internecine struggles of the billposters were legion, and, as one paper explained, “it took a husky man to keep his bills in sight” for more than a few hours (fig. 3).6 Before the 1870s it was unheard of to lease or rent space and, even after, such practices constituted only a fraction of the business. It was even more rare for a lease to go uncontested. Such was the case in the fierce rivalry between the Brooklyn billposters and former partners “Big” John Kenny and Thomas Murphy in the late 1870s. It started casually enough, with one billposter placing lecture bills over the other’s theatrical posters, both claiming their right to that site. Competition soon escalated, so that “[w]hen the employees of one firm spotted a bill posted by the other, they tore it down and trampled it in the dust. . . . Bill Boards were smashed and so were heads.” Kenny’s men were known to “decorate the eyes” of Murphy’s, according to the Brooklyn Eagle, but they did so with less than full mouthfuls of teeth, courtesy of Murphy’s men. By the time Kenny and a henchman were sentenced to the state penitentiary, iron bars, clubs, and even an ax had been called into service, along with the usual paper and paste pot of the billposter’s trade.7 The story of these gentlemen unfortunately does not end here. For Kenny, jail did have a palliative effect, for upon his release he reunited with Murphy, restoring their partnership and fortifying them both against their four or five remaining rivals.8 But even this hopeful reconciliation and girding of forces could not ensure the success—or health—of both men, as we will soon learn.

The billposters’ brawls as well as their copious “snipes” and “daubs”—terms used to describe the pasting of half sheet (twenty-eight inches by twenty-one inches) or smaller bills on ash cans, telegraph poles, and other spaces, and larger posters on walls or fences without permission—both became part of the street life and the spectacle of the city. They were, after all, heirs apparent to none other than entertainment impresario P. T. Barnum, who, thirty years before circulating his circus caravans and advance cars of billposters across the country, had promoted his American Museum with a range of outdoor advertisements, including banners, men carrying signs through the streets, and staged street events to lure bystanders into his establishment.9 Crowds often formed around the battling billposters, too, as they did for the poster war between the Empire and the Novelty Theaters in New York. As each sought to “outdo each other in securing telegraph poles for advertising purposes,” audiences goaded them on, until, finally, as newspapers reported, “Something like a fistic encounter took place between the rival posters and their followers.” Not until police were installed to uphold an existing ordinance prohibiting the posting of signs on telegraph poles did the ruckus halt, at least temporarily.10 The law had also stepped in some years before, when the same two theaters battled over the telegraph poles on Broadway. In that case, James Johnson and Michael Dempsey, both prizefighters in the employ of the Empire Theater, lighted upon William Boehm putting up bills for the Novelty. What, then, did these gentlemen do? “They knocked [Boehm] down, emptied the pail of paste over him and then, when he regained his feet, chased him down the street.”11 Suffice it to say that the organization, professionalization, and rationalization of the billposting industry still had some way to go.

2. “The Bill-Poster’s Dream,” 1862. Lithograph by B. Derby.

3. “The Battle of the Billboards,” c. 1909. Cartoon drawing by Foster Follet.

Advertising space was not yet construed as real estate. Outdoor advertising was still considered a public spectacle that encompassed all imaginable territory, from chimney tops to curbstones, and from romantic glens to roadside rocks. There was no more tranquil joy for the billposter, said Harper’s Weekly, than in billing and rebilling the common ash barrel, padding it with paste and paper until its obese form was broader than it was long. Indefatigable, the billposter worked under cover of night, hardly sleeping so that he could put up the gigantic bills “which cover fences and sides of houses.”12 Few paid regard to the inviolability of private and public property. Overnight the visual landscape of the city itself could be transformed, as in New York in the late 1860s, when the construction of the new elevated railways meant that as fast as the pillars for tracks and risers for stairways went up, they were slathered in paper and paste.13 The platforms helped bring advertisements to new heights, as billposters scrambled to cover chimneys and church steeples with bills to be seen from the “el.” Not all riders might see such ads, though, since after the tops, sides, and interiors of the trains were filled with advertising signs, the windows began to be covered with them, too.14 Not all practices were even so civilized. One enterprising but morbid billposter in Pittsburgh gained a billposting record “second to none” by posting a half-sheet on the “carcass of a horse while the body was still warm.”15 Another painted on the fence of a cemetery, “Use Jones’s bottled ale if you would keep out of here.”16 Every space was fair. Looking to the heavens, some predicted that “[s]oon it will be possible to project from an electrical machine at night advertisements on the clouds.”17

Most outdoor advertisers planted themselves more firmly on earth, where nature itself could serve as ample canvas for the sign painter’s craft. In the 1860s and 1870s, the heyday of patent medicines in the United States, even sparsely settled areas (especially those in view of railway lines or steamboats) sported white-painted rocks, trees, and bluffs boasting the benefits of such nostrums as St. Jacob’s Oil; Buchu (recommended for everything from syphilis to rheumatism); Jones’s Tonic (“a Sure Cure for Paralysis, Vertigo, Insomnia, Jim Jams,” etc.); and a variety of “Anti-bilious Pills.” Despite the passage of laws in several states in the 1870s prohibiting landscape advertising, over the next few decades an even greater variety of signs graced nature. In the 1880s, the Bull Durham tobacco company hired four sets of painters to decorate good rocks and barns across the nation. Mail Pouch chewing tobacco competed with them for barns starting in 1897. The trademarked bull and pouch found themselves in good stead with huge notices not only for “snake oils” (as the patent medicines came to be known) but for plasters, powders, soaps, polishes, hair dyes, chewing gum, and a variety of cigars and cigarettes.18

When novelist William Dean Howells wrote in 1884 of the king of mineral oil paint, Silas Lapham, who saw nothing “so very sacred” about the rocks along a river to prevent him from painting them with ads in three colors, he did not exaggerate.19 Lapham compared well to real historical actors, such as P. H. Drake, who had an entire mountainside forest chopped down “so Pennsylvania Railroad passengers could read about Plantation Bitters in letters four hundred feet high.” Drake had nothing on Sam Houghteling, cofounder in 1870 of the first nationwide paint service (Bradbury and Houghteling), who once boasted “I’ve painted on rocks while standing up to my neck in water” and “put the name of ‘Vitality Bitters’ on Lookout Mountain.” Speaking of his exploits after nearly thirty years in the business, Houghteling, by then a millionaire known as “Hote,” continued to brag: “‘I guess I have desecrated more nature than any man in the United States.” “And what of it?” he said. “There’s not a town or village I ain’t been into.” Hote’s greatest caper was to paint a gargantuan sign for St. Jacob’s Oil on a rock across from one of Niagara Fall’s prime vistas. Such ads galvanized the New York State Legislature to regulate landscape advertising on government property, and by the first years of the twentieth century, public lands around the falls were wiped clean, although painted ads still loomed on nearby private property. Still, some could not help but admire Hote’s pluck. Without naming names, Scribner’s magazine published an article about the painter’s “handiwork high up on the colossal escarpments of Echo Cañon; again on the somber granite of the cliffs of Weber; further west on the arid rocks of Humboldt; even on the forlorn wigwams of the Piutes, straggling over the fallow desert, and continuing over the Sierras and down the golden valley of the Sacramento—sign after sign high above the levee, and often in position the manner of reaching which was inexplicable.”20

Like the New York City sign painters whose work blocked the streets with curious onlookers, and like the rural billposters who were followed by gaping country boys wherever they went, Hote often gathered a crowd of both admirers and detractors. Yet, like others who succeeded in the business, he was both fleet of foot and had the gift of gab, able to lull the farmer or the nature seeker into seeing the value of his artifice and to then beat a hasty retreat.21 Proper permissions or payments for the use of private or public properties were not, in other words, priorities. Farmers whose barns were in need of a good, protective coating of paint gladly loaned their spaces for free, though those who held out might get a pocket watch or a magazine subscription as payment.22 Rarely was money exchanged or leases signed.

Sign painters and billposters sometimes followed practices established by the circus and theatrical managers they often worked for and offered show tickets to property owners who allowed the use of their space. In fact, the extensive distribution of circus tickets and theater passes (giving way to the phrase “papering” the house) led to its own underground economy. Unscrupulous billposters would trade their supply of tickets for tobacco and alcohol. Theatrical props were borrowed in exchange for tickets. Keepers of coal yards and owners of fenced vacant lots could get two theater tickets for every night of the season, while any business with its ash barrel out front could acquire tickets as well. With all of these tickets in circulation, avid theatergoers could easily and cheaply feed their habit through the illicit trade in “billboard tickets.” It was enough of a problem that when theatrical managers discussed starting a union in 1891, they resolved, among other things, to “restrain the growth of the pernicious system of lithograph and billboard passes.”23

From around the 1790s on, circuses, traveling menageries, and theatrical performers (who were among the earliest and most extensive users of outdoor advertising) had advertised with handbills and small posters that relied heavily on text, a few stock images, and just one color of ink. As the size and extent of the shows expanded in the nineteenth century, so did the means to market the events, especially as the printing trade expanded in step with show business.24 New technologies of cheaper forms of woodblock printing that permitted larger sizes and more illustrations and colors; then stone lithography, whose multicolored prints best captured the tones and clarity of oil paintings; and, finally, mechanized, high-speed printing presses and paper-folding equipment led to the creation of bigger and more spectacular posters. Prior to these developments, circus and theater bills might measure twelve or eighteen inches long and include a black-and-white woodcut portrait of the proprietor or an actor, but now they featured dramatic scenes or performances that a patron could expect to see at the show, presented in four colors. Until they became more affordable in the last few decades of the 1800s, color or chromolithographs for advertising were generally limited to one-sheet prints (twenty-eight inches by forty-two inches—the size of the lithographic stone, which became a standard measure for posters), which hung in shop windows.25 Thereafter, a world of color and imagery exploded onto the public landscape. In 1878, when Strobridge Lithograph Company of Cincinnati, one of the premium show printers in the country, exhibited its first twenty-four-sheet lithographed poster, “Eliza Crossing the Ice,” from the traveling show of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, public interest was “so great that the Mayor was obliged to call out extra police to handle the crowds.” For years after, audiences continued to thrill at the colorful pictures of Eliza leaping over the floating cakes of ice to escape the bloodhounds (fig. 4).26

To audiences unaccustomed to seeing a range and vitality of colors in print, the posters comprised an awesome sight, particularly as competing showmen—including the Barnum and Bailey, W. W. Cole, and Sells-Forepaugh Circuses, as well as Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show—upped the size and drama year after year, with forty-eight-sheet, sixty-four-sheet, and one-hundred-sheet posters, some in six and eight colors (fig. 5). The Ringling Brothers Circus even constructed a 357-sheet display in Chicago, 25 feet high and 120 feet long.27 While the size and colorful dramatic pictorials of the circus postings were surely impressive, most overwhelming was their quantity and repetition scattered around a town, sometimes leaving barely even a window uncovered. Special bills, banners, and streamers were produced to fit every nook and cranny, big and small, narrow or wide. A special advertisment called a “rat sheet” or a “flaming poster” was sometimes used to paste over competitors’ signs and to defame rival companies, a practice not limited to circuses.28 It is no wonder that Barnum and Bailey distributed nearly 1.5 million sheets of posters for its 1888 season alone, or so they professed. Local papers argued over how many sheets a show had used for their city, with numbers ranging from five thousand to eighty thousand. Rival fi...

Table of contents

- COVER PAGE

- BUYWAYS

- TITLE PAGE

- COPYRIGHT PAGE

- INTRODUCTION

- CHAPTER 1: BEFORE THE CAR

- PART 1: PRODUCING A LANDSCAPE OF SIGNS

- PART 2: DISTRIBUTING TRAFFIC AND TRADE

- PART 3: “THE BILLBOARD WAR”

- ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- NOTES

- BIBLIOGRAPHY

- ILLUSTRATION CREDITS