- 196 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Probing Understanding

About this book

This work aims to provide teachers at all levels and in all subjects with a greater range of practical methods for probing their students' understanding. These probes are presented in the manner of a starting set, to act as a stimulus to invention, rather than as a comprehensive list.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Topic

EducationSubtopic

Education GeneralChapter 1

The Nature of Understanding

‘What are you learning?’ asked the visitor to the classroom. ‘Not much’, replied the 14-year-old student. ‘Right now I have to understand South America’.

Presumably the student’s teacher told her that understanding South America was what she had to do, but what does it mean? What is involved in understanding South America, or the French Revolution or quadratic equations or acids and bases or musical notation or impressionist painting or Japanese grammar? And how could one test whether a student understands these things?

It is important to answer these questions, since almost every statement of aims for education, whether addressed to a whole school system, a single year of education, a subject syllabus, or even a single lesson, now includes understanding as an important outcome, a higher form of learning than rote acquisition of knowledge. It was not always so, as a comparison of present-day and 1930s school tests or content-specific tests described in the Mental Measurements Year-books (e.g., Buros, 1938), will show. The tests of fifty years ago are largely measures of ability to recall facts or to apply standard algorithms, while those of today more commonly make an effort to see whether the knowledge can be used to solve novel problems. The publication of the well-known taxonomy of educational objectives (Bloom, 1956) both reflected and spurred the widespread acceptance, thirty years ago, of the need to promote understanding. Since then operational definitions of understanding have developed for each school subject, definitions which spread from teacher to teacher through sharing of ideas about tests or through the more effective controls of central examination authorities or textbooks that contain sample questions. Texts even manage to spread ideas so that question styles in a subject are often virtually identical in widely separated countries.

There is nothing wrong with an operational definition of a complex construct like understanding, provided that we recognize that the definition is not the only possible way of measuring it. Restriction of measurement to one form, or too small a number of forms, can distort the construct and lead to neglect of important aspects of it. This, of course, has come to be recognized for another widely-used construct, intelligence, where the Stanford-Binet style of test was dominant for a long time but is now paralleled by different styles such as Raven’s progressive matrices and individually-taken tests like the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children.

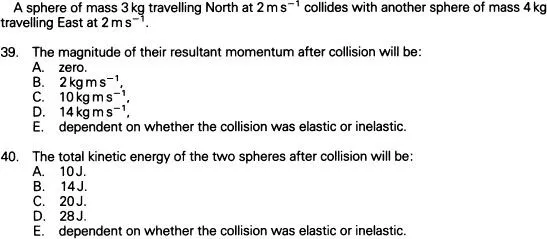

In the case of understanding, a limited definition will have a restricting effect on teaching and learning. In physics, for example, tests of understanding in Australia and America are mainly short problems such as in Figure 1.1; extended explanations of physical phenomena are required rarely. We (Gunstone and White, 1981) found that many first-year university students of physics could not write explanations of simple phenomena such as the acceleration of a falling object, even though they had passed a difficult entry test of one hundred problems. Probably that deficiency resulted from neglecting that aspect of understanding in tests and in teaching. If it were tested, either in an external examination or by the teacher, it would be taught and learned.

Our concern is that when the range of procedures for testing understanding is narrow, the understanding that schools promote is limited and lop-sided. Since we value understanding and believe that there is a direct connection between forms of testing and what is taught and learned, we want to broaden the repertoire of styles of tests that teachers use. That is the purpose of this book.

A limited range of tests promotes limited forms of understanding, while good learning styles should follow from frequent experience with diverse test forms. But are all forms useful? Which should be used for what purpose? What sorts exist? In order to see what possibilities there are for tests beyond those in common use we need to go beyond operational definitions of understanding and describe directly what we take it to mean. Then we can see the limitations of present tests and how they should be supplemented.

We could try to define understanding in a sentence, but a simple definition cannot encompass all the facets of so complex a concept. Indeed we feel that simple definitions are partly responsible for the current limited appreciation of understanding in teaching, learning and assessment. An extensive description of understanding is to be preferred.

Figure 1.1: Example of problem typically used to measure understanding in physics (from Richard T. White, 1977, Solving Physics Problems, with the permission of the publisher, McGraw-Hill Book Company, Sydney)

Part of the difficulty in describing understanding is that the word is applied to a range of targets. People mean rather different things when they say ‘I don’t understand poetry’, ‘I don’t understand what he said’, or ‘I don’t understand my children’. A first step in describing understanding is to sort out the targets we talk about, and then try to see what lies behind understanding of each.

We find it helpful to specify six targets: understanding of concepts, whole disciplines, single elements of knowledge, extensive communications, situations, and people. We will try to spell out what forms of knowledge lie behind each, before considering what new tests are needed.

Understanding of Concepts

If you want to know the meaning of a word like democracy or energy, you can go to a dictionary for a definition of it, but that definition alone is hardly likely to be sufficient for you to feel that you understand the term to any substantial degree. For understanding, you would want to know more about it. That is, to understand a concept you must have in your memory some information about it.

Many theories of learning concentrate on one form of information, that of verbal knowledge or propositions (e.g., Ausubel, 1968), but Gagné and White (1978) described a more complete set in which images, episodes, and intellectual skills complement propositions as elements of memory. To these we would add strings and motor skills as two further elements that may be relevant to understanding. We need to describe each of these six types of knowledge before we consider how they are involved in understanding of concepts.

Propositions are facts, opinions, or beliefs, such as ‘Democracy is the form of government in the United States’ or ‘There are many forms of energy’. Whether these propositions are correct or not may make little or no difference to the way they are stored in memory or to how they bear on understanding, so we will not distinguish between facts and beliefs. After all, today’s fact may be tomorrow’s superstition or fallacy. We may believe that the atom’s fundamental particles are the proton, neutron, and electron, only to find that a revolution in physics has swept this ‘fact’ away.

It is, however, worth distinguishing strings from propositions because the two sorts of element are learned and stored differently. Strings are fixed in form, whereas a proposition is an encoding of a meaning where although the meaning is fixed the form of representation is plastic. Thus the two earlier examples could be represented as ‘The United States is a democracy’ and ‘Energy has many forms’ without changing the proposition. Such a change in form does not happen with a string such as the Gettysburg address or the Lord’s Prayer. Although both the address and the prayer can be expressed in other ways, the typical way of storing them is as strings, unvarying forms. Other examples of strings are proverbs, multiplication tables, scientific laws, mnemonics, and poems.

Images are mental representations of sensory perceptions, which are often visual but can be related to any of the senses. Examples are the mental picture of a voting paper or the feel of ‘springiness’ in a plunger compressing air in a pump.

Episodes are memories of events that you think happened to you or that you witnessed, such as the recollection of voting in the last election or of doing an experiment to measure the energy released when a quantity of fuel is burned.

Intellectual skills are capacities to carry out classes of tasks, such as being able to vote validly in a preferential system or being able to substitute values in a formula such as KE = ½ mv2. They are memories of procedures. It is important to distinguish between the verbal statement of the procedure and the capacity to perform it. If someone asks you how to distinguish cats from dogs your answer will consist of verbal knowledge, propositions, which you could possess without actually being able to use them to tell cats from dogs. Being able to distinguish the two is the intellectual skill. Alternatively, you might be able to perform the skill without being able to describe how you do it. It is much the same with motor skills. They, too, are capacities to perform classes of tasks, but physical ones rather than mental. Examples are being able to work a voting machine or to wind up a clock. Again, the skill of being able to perform the task is a different form of knowledge from the propositions that describe how it is done. Anyone who doubts that should try to write a description of how to ride a bicycle.

In addition to the six types of knowledge that we have just described, we find it helpful to think of a seventh, more general type called cognitive strategies. Cognitive strategies are broad skills used in thinking and learning, such as being able to maintain attention to the task in hand, deducing and inducing, perceiving ambiguities, sorting out relevant from irrelevant information, determining a purpose, and so on. Unlike the other six forms we have described, they are not subject-specific. All of the others tell you something about a particular concept, while cognitive strategies are more to do with general ways of thinking. They will turn out to be important when we consider how understanding is developed, but in considering what we mean by understanding of a concept we will restrict our discussion to the other six types of knowledge.

Our definition of a person’s understanding of democracy is that it is the set of propositions, strings, images, episodes, and intellectual and motor skills that the person associates with the label ‘democracy’. The richer this set, the better its separate elements are linked with each other, and the clearer each element is formulated, then the greater the understanding.

If the definition were left at that point it would imply that as long as two people had the same amount of knowledge about a topic, equally clear and similarly inter-linked, their understandings would be the same. This would not be sensible, since the details of what they know must affect their understandings. The elements of one person’s knowledge may be far more central, more important, than those of the other. Yet it is not easy to say which elements matter. It is doubtful even whether any particular element can be specified as essential to understanding. A definition of the concept may be important, yet concepts can be understood without knowing the definition. Young children, for instance, can have a reasonable understanding of a concept like ‘mushroom’ without being able to define it. A string such as ‘Democracy is government of the people, by the people, for the people’ may be part of an understanding of democracy, but can hardly be asserted to be essential to it. Also, people will differ in the value they place on such a string as a contributor to understanding.

The foregoing points show that it is not easy to rate a person’s understanding and give it a summary value. One person may know more about democracy than another, but unless the second person’s knowledge is a subset of the first’s it is not certain that the first has the better understanding. The few things that the second person knows that the first does not may be quite important contributors to understanding. Even if the first person does know all that the other does and more, we would have to consider whether the extra knowledge adds to or subtracts from understanding.

Several points emerge from this discussion. The first is that understanding of a concept is not a dichotomous state, but a continuum. Language traps us here, because we say ‘I understand it’ or ‘He does not understand’ when we really mean the level of understanding is above or below some arbitrarily set degree. Everyone understands to some degree anything they know something about. It also follows that understanding is never complete; for we can always add more knowledge, another episode, say, or refine an image, or see new links between things we know already. Even to think in terms of degree or level of understanding can be misleading, because it implies that the construct is unidimensional when the discussion about whether one person understands better than another shows that it is multi-dimensional. I may know more about democracy than you, but your knowledge is sharper, more precise; I may have more propositions about it, but you have more episodes. Which of us then understands better? A consequence of this argument is the assertion that a valid measure of understanding of a concept involves eliciting the full set of elements the person has in memory about it. Also, assessment of the elicited set is subjective, as it depends on the weights the assessor gives to particular elements. Because I can define democracy, one judge may rate my understanding higher than yours; but because you have lived democracy and have episodes about it, another judge may prefer your understanding. These points will recur in later chapters when we look at each technique for probing understanding.

Understanding of Whole Disciplines

The points that have been made about understanding of concepts apply with even greater force to the understanding of whole disciplines. The answer to the question, ‘Did Einstein understand physics?’ can only be ‘to a degree’. The question ‘Did Einstein understand physics better than Newton did?’ might be answered ‘yes’, because we could judge that Einstein had all the relevant propositions and skills that Newton did, plus a good number more gained from his own work and the discoveries others made in the intervening centuries. Einstein’s and Newton’s images and episodes would have differed, but we might accept that this would not constitute a vital difference in their understandings. The question ‘Did Einstein understand physics better than Bohr?’ is much less easy to answer. We might value differently the contributions of each to knowledge, but it is hard to say whether the things Einstein believed about physics which his contemporary, Bohr, did not are more central to understanding of the subject than those that Bohr did not share with Einstein.

This argument implies that there is no central core of knowledge which is essential to the understanding of a discipline. That is not to say that all knowledge is of equal value or relevance in understanding. The judgement of that relevance must, however, be subjective. We are prepared to say that the proposition ‘Shakespeare presented a Tudor version of the Wars of the Roses’ is more central to the understanding of his plays than ‘Boys played the parts of women in Shakespeare’s time’, or that ‘A force is a push or a pull’ is more central to the understanding of force than ‘There are four fundamental sorts of force in the universe’, but others may not agree.

Further subjectivity comes when we consider the person who is doing the understanding. We are more tolerant of the amount of knowledge that children should have before we say that they understand than we are for adults, especially adults who have a responsibility to know. We might say ‘The Prime Minister does not understand the relation between President and Congress’ and ‘John Doe (year-10-student) understands the relation between President and Congress’ while accepting that the Prime Minister does know much more about it than John Doe does. We just require more of Prime Ministers. Such is their lot.

In sum, understanding of a concept or of a discipline is a continuous function of the person’s knowledge, is not a dichotomy and is not linear in extent. To say whether someone understands is a subjective judgement which varies with the judge and with the status of the person who is being judged. Knowledge varies in its relevance to understanding, but this relevance is also a subjective judgement.

Understanding of Single Elements of Knowledge

Some different points arise when we consider the understanding of a single element, such as ‘Longfellow wrote epic poems’. This proposition contributes to the understanding of the concepts of Longfellow and epic poems, but cannot be understood unless its believers or recipients have sufficient other elements associated with the labels ‘Longfellow’, ‘wrote’, ‘epic’, and ‘poems’ for each of these components to be understood to a reasonable degree. Skills of grammatical usage come into it too, since Longfellow has to be recognized as the name of a person even if nothing else is known about him. Just as it was not possible to specify the essential elements for understanding of a concept or discipline, so it is not possible to say which elements must be part of the constituent concepts in a proposition for it to be understood. It is again subjective.

Understanding of another of the six forms of element, intellectual skills, requires something more. Gagné (1965) defined several types of intellectual skills, of which one of the most important is algorithmic or rule-following knowledge. Rules can be learned as a procedure to be followed witho...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Preface

- Chapter 1 The Nature of Understanding

- Chapter 2 Concept Mapping

- Chapter 3 Prediction — Observation — Explanation

- Chapter 4 Interviews about Instances and Events

- Chapter 5 Interviews about Concepts

- Chapter 6 Drawings

- Chapter 7 Fortune Lines

- Chapter 8 Relational Diagrams

- Chapter 9 Word Association

- Chapter 10 Question Production

- Chapter 11 Validity and Reliability

- References

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Probing Understanding by Richard White,Richard Gunstone in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.