- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

One of the most brilliant and influential international relations scholars of his generation, Joseph S. Nye Jr. is one of the few academics to have served at the very highest levels of US government.This volumecollects together many of his key writings for the first time as well as new material, and an important concluding essay which examines the relevance of international relations in practical policymaking.This book addresses: * America's post-Cold War role in international affairs* the ethics of foreign policy* the information revolution* terrorism.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Power in the Global Information Age by Joseph S. Nye Jr. in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & International Relations. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Hard and soft power

International politics has long been described in terms of states seeking power and security in an anarchic world. States form alliances and balance the power of others in order to preserve their independence. Traditionally, we spoke of states as unitary rational actors. “France allied with Britain because it feared Germany.” There was little room for morality or idealism – or for actors other than states. When I first studied the subject, towering figures like E. H. Carr and Hans Morgenthau were warning against the misguided idealism that had helped produce the catastrophes of the first half of the twentieth century.1

As a first approximation in most situations, the simple propositions of realism are still the best models we have to guide our thinking. That is why I start this collection of essays with three essays on the power and limits of realism. Realist models are parsimonious, intuitive, sometimes historically grounded, and often provide useful rules of thumb for policy makers. For example, when I was responsible for East Asian policy in the Clinton Administration Defense Department, I relied partly on realism to help redesign a floundering policy. At that time, many people considered the US–Japan security treaty to be an obsolete relic of the Cold War. Unlike Europe, where a web of institutions had knit previous enemies together, East Asian states had never come fully to terms with the politics of the 1930s, and mistrust was strong. Some Americans feared Japan as an economic rival; others feared the rise of Chinese power, and felt that the United States should play the two against each other. Still others urged the containment of China before it became too strong.

As I looked at the three-country East Asian balance of power, it seemed likely that it would eventually evolve into two against one. By reinforcing rather than discarding the US–Japan security alliance, the United States could ensure that it was part of the pair rather than be isolated. From that position of strength, the Americans could afford to engage China economically and socially and see whether such forces would eventually transform China. Rather than turning to military containment, which would confirm China as an enemy, the US pursued engagement while it consolidated its alliance with Japan in the triangular balance, secure in the knowledge that if engagement failed to work, there was a strong fallback position.2 This strategy involved elements of liberal theory about the long-term effects of trade, social contacts, and democracy but it rested on a hard core of realist analysis.

As much as I admire the parsimony of realist models, I have always been interested in the aspects of world politics that the Occam’s razor of realism shaves away. As a graduate student, I remember taking a course from Morgenthau and being impressed by the simple clarity of his realism. But I also remember asking him questions about ideas and social interactions that he tended to sweep aside. I never felt I received adequate answers. Decades later, scholars interested in how ideas shape identities and how social forces lead states to redefine their national interests labeled their new approach “constructivism.” In some ways, as the essays in Parts 3 and 4 illustrate, I was interested in constructivism well before the term was invented.

Perhaps that is why I entered the field of international politics through a side door rather than the main entry. I started in comparative politics in what many regarded as a peripheral area. At that time I wrote my thesis on whether the ideas of Pan-Africanism, so prevalent in the early 1960s, would help the leaders of newly independent states in East Africa hold together their common market. Economic rationality pointed in the same direction. Their ensuing failure was not because of realism as much as social forces within each state. My observations on these issues appear in the essay below on “Nationalism, statesmen, and the size of African states.”

Field work in East Africa led me to regional integration theories as I tried to make sense of what I found, and testing those theories in turn led to further field work in Central America and Europe. I found myself focusing on the impact of trade, migration, social contacts, and ideas in changing identities, attitudes, and definitions of national self-interest. Regional integration theory flourished in the 1960s when there was a good deal of optimism that the example of European economic integration would be followed in other parts of the world. It was a good laboratory for developing ideas outside the realist mainstream, and some of the insights carried over into my work on interdependence and regimes, but the field dried up when the optimism about regional integration declined.3 That experience serves as a reminder of the way that theorizing in our field is affected by current events in the world.

In 1968, Robert O. Keohane and I were among a group of young scholars invited to join the editorial board of the journal International Organization. I had always considered the journal’s focus on legal and formal institutions such as the United Nations to be rather dull, and Keohane and I said so at the first meeting. We argued that the world was full of international organization with a small “i” and small “o” which the journal totally ignored. We were invited to demonstrate what we meant. The result was a special issue on “transnational relations and world politics.” We edited a set of essays that highlighted the role of trade, money, multinational corporations, NGOs, the Catholic Church, terrorists, and others.4

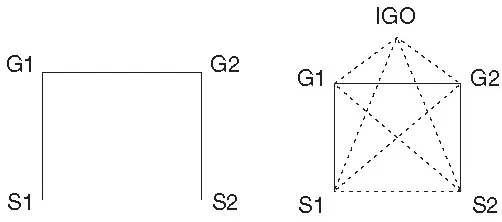

We argued that the realist approach to world politics discarded too much important information. As the little diagram below illustrates, realists focused on government-to-government interactions with domestic societies having an impact only through their governments. But we felt that direct transnational interactions of citizens and groups with other government and inter-governmental organizations often created interesting new coalitions and outcomes in world politics. Rather than the simple “inverted U” relationship in the first image above, our volume presented evidence that a complex star shaped web of relationships was evolving.

G= Government

S= Society

IGO= Inter-governmental organization

Figure 1.1

Our book was generally well received, but the common reaction by realists was that we had shown a spotlight on marginal issues, and lacked any theory to show how these aspects related to the “real” issues. At best, we had illuminated some oddities. Now, as I will argue below and as the essays in Parts 2 and 4 illustrate, transnational relations can no longer be ignored by realists. On September 11, 2001, a transnational terrorist organization killed more Americans than the state of Japan did in December 1941. The national security strategy of the United States now states that “we are menaced less by fleets and armies than by catastrophic technologies falling into the hands of the embittered few.” Instead of strategic rivalry, “today the world’s great powers find ourselves on the same side – united by common dangers of terrorist violence and chaos.”5 The “star” of transnational relations depicted in the second image above has gone from an amusing detail to a critical picture.

Keohane and I subsequently published Power and Interdependence, designed to show how interdependence (military, economic, ecological, social) can serve as a source of power.6 In some settings, military instruments are trumps, but in others economic interdependence may be more useful. The oil embargo of 1973 and President Nixon’s delinking of the dollar from gold meant that there was some growing interest in these ideas. The first two articles in Part 4 are illustrative of our concern at that time.

We developed an ideal type that we called complex interdependence, by reversing three realist assumptions: that states were the only significant actors, that force was the dominant instrument, and that security was the primary goal. We argued that as some parts of world politics began to approximate the conditions of complex interdependence (e.g. US–Canada and intra-European relations), we should expect to see new political processes, coalitions, and outcomes that would be anomalous from a traditional realist perspective. We did not discard realism, but we argued that in some instances, “marginal” dimensions from a realist view could become central to good explanation. These insights stood us in good stead in terms of predicting how Europe would evolve after the Cold War ended. While some realists were predicting that Germany would break away from the European Union, develop nuclear weapons, and ally with Russia, we felt that the institutions of the European Union would hold together and Brussels would serve as a magnet that would orient Central Europe westward.7

While Keohane went on to explore and develop the neo-liberal theory of institutions, I took a detour into practical policy work as a deputy undersecretary in the Carter Administration State Department. I was responsible for developing and implementing policy on the non-proliferation of nuclear weapons. It was shortly after the 1973 oil crisis, and there was a widespread belief that plutonium would be the energy source of the future. Governments were subsidizing reprocessing plants to extract plutonium from spent nuclear fuel and building experimental breeder reactors to produce plutonium. France had sold a reprocessing plant to Pakistan. The Carter Administration argued that the real costs of plutonium were disguised by the subsidies, and that spreading a fuel that was an ingredient of nuclear weapons created grave risks.

We were bitterly opposed by the nuclear industry at home and abroad. I found it ironic to be the subject of personal attacks by a transnational coalition whose common interests in nuclear energy were greater than national differences between them. A 1977 international conference in Persepolis, Iran that condemned Carter’s policies represented more the views of nuclear agencies and organizations rather than most foreign ministries. I remember thinking that “this is what I wrote about,” but I never expected to experience it so directly! Part of our policy response was to design and organize a high profile multi-year inter-governmental study of plutonium economics and proliferation risks as a means of slowing the momentum of the transnational nuclear elites, and to spread more new information as an alternative way of framing the issue. This was a policy issue where I was able to build upon the insights developed in my academic work.

The intensity of my two years of policy focus on nuclear proliferation led to a decade of academic concern about the role of nuclear weapons and whether institutional arrangements could help control them. It also led to a fascination with a set of moral questions. How could one justify the possession of nuclear weapons – by the superpowers or by anyone? The question remains relevant to this day, and my answer is reprinted in the essay “NPT: the logic of inequality.”8 This in turn led me to ask broader questions about the role of morality in international politics more generally. Much of what I published in that decade focused on such issues, and I still stand by the views reprinted in “Ethics and foreign policy.” The moral dilemmas and framework remain relevant, and a strong case can be made that the moral issues in world politics are likely to become more prominent as the information revolution and democratization spread power to larger numbers of citizens around the world.9

Toward the end of the 1980s, as the Soviet nuclear superpower declined, the conventional wisdom was that the United States would follow suit. Paul Kennedy’s The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers made the bestseller list.10 Some analysts believed that geo-economics was replacing geo-politics and that Germany and Japan would become the new challengers to the United States in world politics. Some books even predicted a coming war with Japan. I felt these predictions were mistaken, and that the United States had a number of sources of power other than its nuclear status. I argued that the United States was likely to remain on top in military and economic power, but also in a third power resource that I called soft power. I had always been interested in the way that culture and ideas could contribute to power. I developed the concept of soft power to refer to the power of attraction that often grows out of culture and values and is too frequently neglected.

As the essays in Part 2 explain in greater detail, military power and economic power are both examples of “hard” command power that can be used to get others to change their position. Hard power can rest on inducements (“carrots”) or threats (“sticks”). But there is also an indirect way to get the outcomes that you want that could be called “the second face of power.” A country may obtain its preferred outcomes in world politics because other countries want to follow it, admiring its values, emulating its example, aspiring to its level of prosperity and openness. In this sense, it is just as important to set the agenda and attract others in world politics as it is to force them to change through the threat or use of military or economic weapons. This soft power – getting others to want the outcomes that you want – co-opts people rather than coerces them. The ability to establish preferences tends to be associated with intangible power resources such as an attractive culture, political values and institutions, and policies that are seen as legitimate or having moral authority. If I can get you to want to do what I want, then I do not have to force you to do what you do not want. If a country represents values that others want to follow, it will cost less to lead.

I first developed the concept of “soft power” in Bound to Lead, a book I wrote in 1989. In the ensuing decade and a half, I have been pleased to see the term enter the public discourse, being used by the U.S. Secretary of State, the British Foreign Minister, political leaders, and editorial writers as well as academics around the world. At the same time, however, I have felt frustrated to see it often misused and trivialized as merely the influence of Coca-Cola and blue jeans. It is far more than that. The ability of a country to attract others arises from its culture, its values and domestic practices, and the perceived legitimacy of its foreign policies.

In the early 1990s I was trying to explore the dimensions of soft power and what was being called “a new world order” when I was again lured into policy work after Bill Clinton’s election. When I returned to academia, neo-liberal institutionalism and constructivism had become widely accepted as a legitimate subsidiary approaches. Many scholars were turning their attention to the information revolution and globalization. I felt that the new work on globalization seemed to ignore the earlier literature on interdependence, and that information technology was making soft power more relevant than ever. Keohane and I agreed that much of the writing on these topics was re-inventing the wheel. We regretted the lack of cumulative knowledge in the field, and felt that we should try to relate our earlier work on interdependence...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Acknowledgments

- 1. Hard and Soft Power

- Part 1: The Power and Limits of Realism

- Part 2: America’s Hard and Soft Power

- Part 3: Ideas and Morality

- Part 4: Interdependence, Globalization, and Governance

- Part 5: Praxis and Theory