- 294 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Presents a chronological selection of Watney's writings from the 1990s, with new contextualising introductory and concluding essays and offers a chronicle of the changing and often confusing course of the epidemic.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Imagine Hope by Simon Watney in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Médecine & Prestation de soins de santé. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Ordinary boys*

Only that historian will have the gift of fanning the spark of hope in the past who is firmly convinced that even the dead will not be safe from the enemy if he wins and this enemy has not ceased to be victorious.

Walter Benjamin1

But don’t forget the songs that made you cry, And the ones that saved your life, Yes you’re older now and you’re a clever swine, But they’re the only ones who always stood by you.

Morrissey2

The fiction of our invisibility remains influential.

Neil Bartlett3

In 1947, two years before I was born, The Camera Inc. of Baltimore, USA, published a very up-to-date handbook on Portraiture in their Camarette Photo Library series. The anonymous editors explained in their Foreword that: ‘Amongst all the branches of photography, perhaps portraiture is the most fascinating, for it is the story of people and the interpretation of personality.’4 This admirable and most illuminating text has much to say on such topics as Portraiture at Home (including sections on ‘photographing thin subjects, photographing heavy subjects, groups of two, subjects with glasses’, etc.); Glamour Portraiture (‘star photographs, corrective make-up …glamour photographs for society and royalty’, etc.); Hair-Dos in Portraiture; Principles of Portrait Lighting; Draping the Model; Child Portraiture (including ‘timeless qualities in pictures, holding the child’s attention’, etc.); Portraits for the Home Record; and Portraiture of Men (including ‘use of lighting to bring out features and hair, getting sitter at ease’, etc.).

Needless to say, such manuals continue to proliferate in both Britain and the USA, setting the stage for lives which will in most cases be recalled only through photographic records. I have no idea whether my parents ever actually picked up a book on photography as such. They hardly had to. For the conventions of domestic ‘family’ photography are experienced as second nature, which precisely marks them as densely ideological—as formal as Noh plays, or a well-practised round of bell-pulls on Sunday morning. What fascinates me initially about the Camarette Photo Library book is its system of categories. More than two-thirds of the text is given over to portraits of women, usually alone but occasionally in pairs, all acknowledging the role of technique and lighting in constructing the impression of ‘strength of character’, ‘motherliness’, ‘femininity’… Yet as soon as we turn to children, the desired values are very different. Here ‘spontaneity’ and ‘humour’ are the order of the day, with the strict injunction that ‘eyes must see something’, and so on.

This could hardly contrast more strongly with the portraits of grown men, who are presented as uniformly grim and unsmiling, or relentlessly avuncular. Yet I am loath to interpret these distinctions as if they simply express some natural order of patriarchal representation. For a start, it is difficult not to conclude that however much idealization is going on in the pictures of women, there is also an admission of the erotic, of a certain quality of play, the sense of pleasure in ‘dressing up’, ‘looking good’… By the same token it is difficult not to feel the immense cultural pressures that have compressed the men into such monotonously joyless appearances, that force them to aspire to stereotypes of ‘the rugged’ or ‘the intellectual’ or ‘the businessman’ which are every bit as constrictive as the roles that their wives, mothers and older daughters are obliged to enact. Only the children seem to have fun, if in a calculatedly ‘cute’ way which means that they are especially droll when ‘serious’. As everyone knows, a ‘serious’ child is an unhappy child, a child who will reflect badly on his or her parents’ duty to keep them happy as nature (or photography) intended. Besides, there’s something ‘funny’ about a serious child, something not quite right…

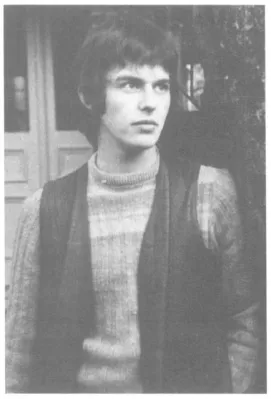

As a gay man approaching 40 who has kept a fairly thorough photographic record of my life since I left home more than twenty years ago, I compare the two sets of images of my life before and after I went away to college with a sense of curiosity and some anxiety. Photography was not much practised in my family, and only a couple of years ago my mother chucked out all the old negatives to ‘make room’. Like many other gay men, I am acutely aware of the moment when I realized that I was not the ‘nice’ little boy in the holiday snaps, that a deception was being perpetrated. Yet it was me who felt like the deceiver, rather than my parents’ image of me. I have almost no photographs of myself between the age of ten or so and my late teens. I was therefore very surprised, on a recent visit to my mother, to find several pictures of myself as a small boy. These are images which I had completely forgotten— as completely as I had forgotten the person I was and the world of childhood to which they offer a few moments of fragile, ambiguous access.

I grew up in the shadow of the various gay scandals of the 1950s, including the notorious Montagu case, though I cannot claim that at the age of five I was aware of the arrest and subsequent imprisonment of Lord Montagu and two other men for ‘homosexual offences’ in 1954. I do, however, remember very clearly only a few years later reading about other such unnatural monsters in my grandmother’s Sunday newspaper, The People. Knowing instantly that I was ‘one of them’. Knowing that I was this new word in my vocabulary, never to be said out loud: ‘queer’. I have a photograph of myself learning to read. My mother tells me that it was taken on holiday, which explains its otherwise anomalous existence. She couldn’t remember who the woman in the picture was. What amazes me is this simple fact: the child is me. And I look fine, a little boy just like millions of other little English boys in the mid 1950s. Yet I am shocked to discover that the picture reveals nothing of the terrible secret that drove me so deeply into myself for so many long irrecoverable years—years that, without photographs, do not exist.

Or perhaps there were signs? Another picture taken a couple of years later shows me hand in hand with a friend, up to our ankles in the sea. Who was he? What did I feel for him? These are questions we all ask ourselves of such images. There I was, steadily growing towards my eventual identity and life as a gay man, yet now I recall next to nothing of those early years. Again, a few years on, another beach with another friend, Midge, whom I adored, but who has now decayed to a single memory— that his parents lived in Kuwait. By this time I had read about myself in The People. I had also begun to have sex with other boys in a fumbling pre-public sort of way. By now I had any number of secrets, and was well aware of the degree to which my knowledge of myself conflicted with the ways other people saw me. What startles me now is a simple and painfully obvious displacement: I have always believed that I was a grotesquely fat and unattractive child, but the little boy who stares back rather cautiously from under his sunhat is neither of these things. I thought I was fat and ugly because I thought I was bad.

Many people will have memories of this order, memories that signal some kind of dysfunction between one’s sense of oneself and one’s parents’ expectations. These are folded in with the larger function of domestic photography, which is to impart the semblance of retrospective coherence to family life, usually more or less chaotic and unpredictable. This narrative function should not be lightly dismissed, for it provides a crucial psychic stabilizer to life—the sense of purpose. Yet gay children are particularly vulnerable to their parents’ fantasies about who they are, fantasies that invariably fail us. The gay child can hardly be expected to understand this, though he feels the sense of failure. How is a child to learn that he is perfectly OK as he is, and that his sexuality and feelings are not his problem but that of his family, and then through no real fault of their own? Who prepares parents for the entirely predictable and intrinsically unremarkable fact that their children may well grow up gay? Not many parents cope as well as Mrs Dumbo. Dumbo is our film.

All too few parents ever have the opportunity or encouragement to imagine parenting in terms that differ significantly from the ways in which they themselves were parented. In a world of great uncertainty, where most pleasures and humiliations alike are lived in silent isolation, it is not surprising that parents should tend to veer towards what they feel to be the safety of the familiar. Not many parents would nod their heads in agreement with John Ashbery’s assertion that we are saved only by what we could never have imagined.5 Gay children are always to some extent the victims of such familiarity, and we learn many ways to hide our cloven hooves, often at terrible personal cost. The gay child who loves and wishes to be loved spares his parents’ feelings at the expense of his own. This pattern may take a lifetime to unlearn. It is often clearly visible to those who know what they are looking for in the smiling photograph of an unmarried son or daughter, framed discreetly on a dressing-table in any household in the land.

We are what our parents most dread, what they have read about in The People and the News of the World and, for that matter, in the Observer. Yet we are also the Family Face. We therefore tend to learn from an early age that appearances are not much to be trusted, that nothing is necessarily what it seems, least of all ourselves. Thus gay children tend not infrequently to lead lives of intense privacy, knowing far more than they can ever reveal, ill at ease with other children, who always find us out… We are there, and we are not there. Yet I am not convinced that we should simply blame photography for the narrowness of its conventional pictures of family life. Indeed, the very determination to put a brave face on things, to show us all smiling as our teeth chattered on the frozen windswept beach or at the washedout picnic, only demonstrates our more or less desperate desire to be happy: a dumb, clumsy, inchoate awareness that somehow life could be better than it is. This is the poignancy and potency of so much domestic photography. It is where we see our past follies and illusions grow clearer (or more damaging) year by year, as much in repetitions as in changes. There I am, standing on the beach, facing the camera. If only I could talk to the child I was, tell him not to worry, tell him that he’s all right as he is, and lovable! Perhaps we spend our entire lives coming back to stare at pictures of the people we once were, mouthing the same reassuring messages that we could never hear when we most needed them? Perhaps this is secretly what family photographs are all about, always giving back the same forlorn and incompatible messages: ‘How happy I was’ and ‘If only I’d known’…

And then we leave home, though home is always there in our head as we struggle to break with the immensely powerful role models offered by our parents, to be ourselves. I look at the generic ‘family’ snaps of my parents with myself and my sister. It’s as if we were all invisible away from the seaside, as if we came to life only as a family on holiday. My father died when I was sixteen. Now, when I shave, I see his face starting back at me from the bathroom mirror: at least his look, if not his actual looks. This was it, their marriage, with all its crushing load of symbols and duties (and relations) that marriage entails. Oh, and love too, if you’re lucky. My Extended Family albums are so very different. This difference might be summarized in the observation that whereas heterosexuals have separations and divorces, gay men usually make friends from the wreckage of failed love affairs. A high proportion of names in my address book, and faces amongst my photographs, are ex-lovers, and in this respect I think I am entirely typical rather than an exception. My photographs and my life coincide with the emergence of modern gay culture. As Neil Bartlett points out, this is ‘something to be struggled for, not dreamt or bought. At this point, our rewriting of history becomes a truly dangerous activity.’6

Our photographs help us learn to be generous and forgiving to ourselves. This is especially important for people who often have to overcome a heavy sense of personal failure: the failure to be what our parents expected. Sadly, some of us never learn that this was our parents’ failure, not ours. So I look back to myself at the age of twenty and cannot help but think how little I had to model my life on that might have given me a stronger sense of selfesteem. In the two decades between that image and pictures of myself with my lover John-Paul today, I am very much aware of the presence of tens of thousands of people like me, who have worked to construct our culture, however uneven and contradictory it may be. Such images carry us through life, like the songs you learn as a teenager—in my case the songs of Dionne Warwick, Aretha Franklin, Billie Holiday—images, like the songs, that do some justice to the complexity of life, its risks and passions, its memories and forgettings. My Extended Family albums contain pictures of my first hitchhiked trips to Europe, the first ever British Gay Pride march, many demonstrations, many parties, many days out and many days at home. Different places, different careers, different lovers, different homes. Yet everywhere I go, the little boy on the beach who I was goes with me. I am still trying to make up to him for what he went through, trying to make amends.

I could not finish this piece without saying something about AIDS. Looking through my own photographs this afternoon—a clear, bright January afternoon—I saw friends who are now sick, some now dead. Beautiful, gifted young gay men who, like me, spent their childhoods in prisons of guilt, finding their feelings reflected and validated in the voice of Judy Garland, or watching Bette Davis in Dark Victory, or reading Cavafy or Auden. We all took great risks, my generation, because great damage and injustice had been done to us, because we had so much catching up to do, through no fault of our own. In a very brief period of time we have defined our own forms of domesticity, perhaps a little more honest and flexible than those we fled—or that threw us out. We were ordinary girls and ordinary boys, growing up and ‘coming out’ at an extraordinary time. There is nothing that the human immunodeficiency virus or its many human allies can do to undermine the historic achievements of the Gay Liberation movement in the lives of literally millions of lesbians and gay men around the world. It is important, however, for us to try to understand the full extent to which we are hated and feared, the extent to which powerful institutions regard gay men as entirely disposable.7 AIDS demonstrates with grim clarity the full extent to which even the...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1 Ordinary boys

- 2 Vito Russo: 1946–90

- 3 School’s out

- 4 Queer epistemology: activism, ‘outing’, and the politics of sexual identities

- 5 Emergent sexual identities and HIV/AIDS

- 6 The killing fields of Europe

- 7 Charles Barber: 1956–92

- 8 Read my lips: AIDS, art & activism

- 9 How to have sax in an epidemic

- 10 Hard won credibility

- 11 Michael Callen: 1955–93

- 12 Dr Simon Mansfield: 1960–93

- 13 AIDS and the politics of queer diaspora

- 14 Derek Jarman 1942–94: a political death

- 15 Numbers and nightmares: HIV/AIDS in Britain

- 16 Art from the pit: some reflections on monuments, memory and AIDS

- 17 In purgatory: the work of Felix Gonzalez-Torres

- 18 Acts of memory

- 19 Signifying AIDS: ‘Global AIDS’, red ribbons and other controversies

- 20 Concorde

- 21 AIDS awareness?

- 22 Moving targets: some reflections on the origins and history of gay men fighting AIDS

- 23 ‘Lifelike’: imagining the bodies of people with AIDS

- 24 The politics of AIDS treatment information activism

- 25 GLF: 25 years on

- 26 These waves of dying friends: gay men, AIDS and multiple loss

- 27 The political significance of statistics in the AIDS Crisis: epidemiology, representation and re-gaying

- 28 Lesbian and gay studies in the age of AIDS

- 29 Imagine hope: AIDS and gay identity