Part I

The cultural complex in the psyche of the group

In this part, the authors focus on the cultural complex as it expresses itself in the psyche of the group. Part I includes historical and contemporary examples of cultural complexes. Authors from several different countries have identified what they consider to be the most potent and disruptive cultural complexes in their respective countries including Australia, Mexico, the United States, England, Japan and Brazil. The focus in these chapters is on the cultural complex as it exists in the collective psyche of the group.

Each author has a unique way of understanding and describing the reality of cultural complexes. Thomas Singer sketches the development and central themes of the theory of cultural complexes and gives historical and contemporary examples of its application. Jacqueline Gerson goes to the history and legend of the Conquest of Mexico to understand a deep sense of inferiority and betrayal in the Mexican psyche. Craig San Roque tells a wild, poetic, impressionistic tale of a weekend in Alice Springs, Central Australia. He takes the reader into the “eye of the storm” of a cultural complex that is devastating the Aboriginal people. Out of the initial sense of confusion and chaos emerges the author’s intuitive creativity reflecting through its own deep responsiveness the profoundly disorienting and destructive effects of the clash of two cultures and their complexes.

Joseph Henderson sees the folly in the eternal, Western “Foot-race for a Prize” which originates in the archetypal pattern of the Olympic games and easily becomes frozen in a cultural complex. Manisha Roy makes a most important distinction between a “cultural archetype” and a cultural complex in her analysis of the perfectionism of the Puritan tradition.

Luigi Zoja elegantly demonstrates the onset of a cultural complex in the encounter between the eternal time of Montezuma and the linear time of Cortés. Toshio Kawai utilizes the novels of Haruki Murakami as a psychological frame to look at postmodern consciousness in Japan. He portrays this postmodern consciousness and its dissociative states of being as symptomatic of a loss of connection to the stable and enduring worlds of mythology and the containing structures of culture and family. Denise G. Ramos dissects the cultural complex of corruption in Brazil in a careful analysis of its collective psyche. Finally, Andrew Samuels takes a careful and critical look at the practice of Western psychotherapy itself as the unwitting carrier of its own cultural complexes.

Chapter 1

The cultural complex and archetypal defenses of the group spirit

Baby Zeus, Elian Gonzales, Constantine’s Sword, and other holy wars (with special attention to “the axis of evil”)

Thomas Singer

Introduction

Much as an airline pilot gives the passengers a brief synopsis of the flight plan, I would like to provide an itinerary for this intuitive flight so that some of the landmarks along the way have a context. The series of seemingly unrelated historical and contemporary episodes which I will be highlighting are linked together by a kind of intuitive logic that seeks to sketch an extension of traditional Jungian theory. Indeed, this chapter is meant to be a “sketch” in the same way that an artist or architect would render a preliminary drawing of a work in progress which will be elaborated over time.

Jung’s earliest work at the Burghölzli led to the development of his theory of complexes which even now forms the foundation of day-to-day clinical work of analytical psychology. In fact, there was a time when the founders of the Jungian tradition considered calling it “complex psychology.” Later, Joseph Henderson created a much needed theoretical space between the personal and archetypal levels of the psyche which he called the “cultural level of the psyche.” This cultural level of the psyche exists both in the conscious and the unconscious. Elaborating Jung’s theory of complexes as it manifests itself in the cultural level of the psyche – conscious and unconscious – is the goal of this chapter. In the effort to sketch this idea, we will be taking a tour which includes stops at Jane Harrison’s study of early Greek religion, Elian Gonzales’ gripping story of loss and political upheaval, James Carroll’s study of anti-Semitism in the history of the Catholic church, current manifestations of the primal psychoanalytic split between Jung and Freud, and finally a comment on the al-Qaeda attack on the West and George W. Bush’s “axis of evil” response. All of these episodes help illustrate the reality of cultural complexes and elucidate a specific type of cultural complex in which archetypal defenses of the group spirit play a primary role.

Jane Harrison’s Themis

Almost 100 years ago, Jane Harrison published Themis: A Study of the Social Origins of Greek Religion, her stunning exploration of matriarchal, pre-Olympian Greek religion (Harrison 1912/1974). Jung’s notion of archetypes and the collective unconscious had not been conceived yet and one can almost feel those seminal insights struggling to get born as Harrison pieces together threads of anthropology, classical studies, archeology, sociology and psychology. Her book reads like a detective story as she seeks to discover the origins of early Greek religion. Her work is named for, inspired by and presided over by the goddess Themis, who embodies the earliest Western ideas of civility and community. Mention of Harrison’s book is a fitting place to begin this contemporary piece of psychological theory making, because not only is it in her spirit of the detective piecing together bits and pieces of “evidence” to get at a whole that this chapter is undertaken, but also one of the central images from her work actually gave birth to this project.

Baby Zeus and Elian Gonzales

The contemporary context of this inquiry begins in exactly the same place as Jane Harrison’s: with a fascination about the origins, underlying meaning and power of collective emotion. Harrison was gripped by the force of collective emotion in its capacity to create gods, social order and a meaningful link between humans, nature and spirit in pre-Olympian Greece. I am equally fascinated by the power of collective emotion to create gods, devils, political movements and social upheaval/transformation in our times. Harrison did not have the concept of the collective unconscious and its archetypes in which to ground her ideas about the origin of social and religious life in early Greece. But she was a keen observer of art, ritual and especially the degree to which collective emotion and its enthusiasms seemed to generate a coherent mythos that linked the natural and social order into a coherent whole. At the epicenter of her quest was the glorious mystery of “The Hymn of the Kouretes.” Through Harrison’s eyes, the image of Baby Zeus surrounded by the protective young male warriors, the Kouretes, comes to life and the very foundations of early Greek religion are unveiled (see Figure 2).

Io, Kouros most Great, I give thee hail, Kronian, Lord of all that is wet and gleaming, thou art come at the head of thy Daimones. To Dike for the Year, Oh, march, and rejoice in the dance and song,

That we make to thee with harps and pipes mingled together, and sing as we come to a stand at thy well-fenced altar.

Io, etc.

For here the shielded Nurturers took thee, a child immortal, from Rhea, and with noise of beating feet hid thee away.

Io, etc.

And the Horai began to be fruitful year by year and Dike to possess mankind, and all wild living things were held about by wealth-loving Peace. Io, etc.

To us also leap for full jars, and leap for fleecy flocks, and leap for fields of fruit, and for hives to bring increase.

Io, etc.

Leap for our Cities, and leap for our sea-borne ships, and leap for our young citizens and for godly Themis.

(Harrison 1912/1974: 7–8)

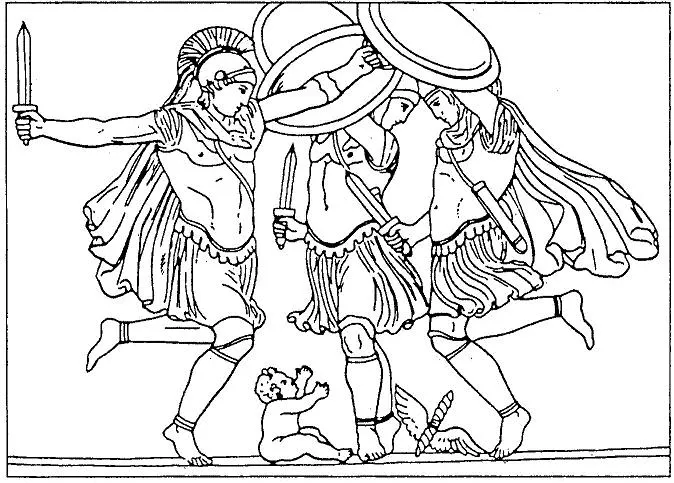

In this terracotta relief from the Greco-Roman era we see the baby Zeus surrounded by his shieldbearing protectors, the Kouretes, also known as the Daimones. Had it not been for them, according to the myth, this child of Rhea and Kronos would have been devoured by his father, who was in the habit of swallowing his children. A Cretan hymn tells the story: “For here the shielded Nurturers took thee, a child immortal, from Rhea, and with noise of beating feet hid thee away.” (Image courtesy of the Archive for Research in Archetypal Symbolism [ARAS], C. G. Jung Institute of San Francisco, San Francisco, California)

Figure 2 The image of Baby Zeus surrounded by the Kouretes

Baby Zeus, who is here referred to as “Kouros most great,” was secretly stolen away from his nursery and handed over to the Kouretes for protection by his mother Rhea, wife of Kronos. She did not want him to suffer the same fate of his older brothers and sisters – namely, to be eaten by his father, Kronos. The young god was shielded from destruction by the Kouretes who, in their youthful energy, leap for the gods and secure the safety and renewal of the crops, the animals, the cities, the ships, the “young citizens,” and for godly Themis.

Several thousand years later in our time, young Elian Gonzales – a Cuban boy – was miraculously plucked from the very sea south of Florida in which his mother had just drowned. She perished trying to flee the economic and political hardship of Castro’s Cuba and start a new life in the “promised land” of the United States. Within a very short period of time, Elian Gonzales became the center of a psychic and political drama that stirred the emotions of at least two nations. The response of Elian’s Cuban American relatives and friends who had already settled in Miami made little sense to most Americans, who do not share the same historical experience or mythic story of their origins, survival, and renewal.

Most well-intentioned, non-Cuban Americans seized by this tragic story felt that the motherless child should be reunited as quickly as possible with his loving father, even if he happened to live in Castro’s Cuba. Most people found themselves thinking: “These Cuban Americans are crazy. Isn’t it obvious that Elian should be returned to his surviving parent?” Indeed, it was the extraordinary power of the non-rational, collective emotion of the Cuban Americans that caught my attention. “Why are they behaving so ‘irrationally’?” I asked myself. It wasn’t until I happened by chance to glance again at the image of Baby Zeus from Jane Harrison’s book that I was able to find a missing link to the story which allowed me to make some sense (at least for myself) of what seemed so irrational and yet was being deeply felt not just by the Cuban Americans, but all the other people caught up in this extraordinary drama. What if Baby Zeus and Elian Gonzales are part of the same story? What if they are linked by a mythic form or archetypal pattern out of which are generated a story line, primal images and deeply powerful, non-rational collective emotion? Elian Gonzales’ miraculous second birth or rebirth as he was plucked from the waters puts him in the realm of the divine child (like Moses), and he becomes the young god who carries all the hopes for the future of a people that sees itself as having been traumatized by a life of cruel oppression. Like Baby Zeus, Elian Gonzales, too, in his vulnerable state of youthful divinity, needs to be protected from destruction by his warrior cousins who rally to his defense. For Elian Gonzales’ “shielded nurterers” to willingly return him to Castro’s Cuba (because now, as a young god, he belongs to all his people, not just his personal family) would be equivalent to the Kouretes sending Baby Zeus back to Kronos. In the mythic imagination of the Cuban American collective, Fidel Castro is the same as Kronos – a destructive father god who would eat his own son, the youthful god. Elian Gonzales’ “crazy cousins” are not so crazy after all. They are the Kouretes, dancing in the frenzy of a collective emotion that seeks to form a protective circle or shield around their young god. The force/libido providing the energy to fuel these incredible sagas comes from the collective emotion mobilized by the plight of a gravely endangered, vulnerable (divine) child who symbolizes the hopes of an entire people. The inevitable, archetypal coupling of the endangered divine child and the protective, warrior Kouretes who surround him are at the heart of the story I want to tell and the theory I want to advance. This old and modern story allows us to jump ahead to anticipate a central thesis of this chapter: an archetypal pattern has formed the core of a contemporary cultural complex.

Donald Kalsched and the Archetypal Defense of the Personal Spirit

Donald Kalsched’s (1996) ground-breaking work in The Inner World of Trauma: Archetypal Defenses of the Personal Spirit forms the next major building block of this chapter. In the summer of 2000, I participated in a conference with Dr. Kalsched in Montana. His paper focused on the inner world of trauma, while my presentation was more about the outer domain where myth, psyche, and politics intersect – a subject which I have explored with others in The Vision Thing: Myth, Politics and Psyche in the World (Singer 2000). I had just stumbled into an imaginal connection between Baby Zeus and Elian Gonzales and was using the image of Baby Zeus surrounded by the Kouretes to illustrate the reality of the collective psyche and the power of collective emotion to generate living myths. Kalsched had not seen this particular image before and he startled with both surprise and instant recognition at the lively representation of the warriors defending Baby Zeus. He immediately knew who they were, correctly identifying them as the Daimones. Indeed, the Kouretes are also known as the Daimones: “Io, Kouros most Great . . . thou art come at the head of thy Daimones” (Harrison 1912/1974: 7).

These prototypes or original Daimones surrounding Baby Zeus are in the same lineage as those characters whom Kalsched a few millennia later would identify as the “archetypal defenses of the personal spirit.” If one thinks of this image psychologically as a portrait of the endangered psyche, one sees clearly that the Daimones have the intra-psychic function of protecting a vulnerable, traumatized youthful Self – be it Baby Zeus, Elian Gonzales, or any other less famous wounded soul. As Kalsched has elaborated, the Daimones have the function of protecting the “personal spirit” when the individual is endangered. In this chapter, I am suggesting that these same Daimones also have the function of protecting the “collective spirit” of the group when it is endangered – be it Cuban-Americans, Jews, blacks, gays or any other traumatized “group soul.” The Daimones are as active in the psychological “outer” world of group life and the protection of its “collective spirit” as they are in the inner, individual world of trauma and the protection of “the personal spirit.” Perhaps they even found their earliest historical expression in group life rather than that of a single person, when the psychology of the individual was less developed and the survival of the group more in the forefront. We have come to appreciate the Daimones again through the Jungian route of recognizing their role in the inner world of trauma. Whether it be in the inner/outer world of the individual or the inner/outer world of the group, the Daimones can serve both a vital self-protective function and can raise havoc with the fury of their attacks directed inwardly in self-torture and outwardly in impenetrability, hostility and ruthlessness. The fortuitous recognition of the connection between Baby Zeus and Elian Gonzales led me to consider an extension of Kalsched’s insights into what might best be summarized in this reformulation of his book’s title: “The group world of trauma: archetypal def...