![]()

Part 1

A framework for developmental psychology

![]()

CHAPTER 1

A brief history of developmental psychology

CONTENTS

The developmental principle

The evolution of development

The emergence of developmental psychology

Fundamental questions in developmental psychology

Conclusion and summary

Further reading

1

The scientific study of children's development began about 150 years ago. Until this comparatively recent period, Western societies did not study the childhood years—from the age of about seven to adolescence—even though early childhood had long been recognised as a distinct period in the life cycle. The coming of the industrial revolution in the 19th century provided an impetus for the systematic study of childhood since it brought with it an increasing need for basic literacy and numeracy in factory workers that was eventually met by the introduction of universal primary education. This, in turn, made it important to study the children's minds so that education itself could become more effective. Other social factors such as increased wealth, better hygiene, and the progressive control of childhood diseases meant that the chances of a baby surviving childhood and growing to adulthood were greatly increased. This increase in survival rates also contributed to a greater focus on understanding development throughout childhood.

The new-found wealth of Western society also extended the period of childhood. As the age at which children began work was gradually raised, the idea of adolescence—as a distinct stage interspersed between childhood and adulthood—became increasingly important. As the 20th century progressed, ever more sophisticated skills were required as technology advanced. This was reflected in a steep rise in the school leaving age. At the beginning of the century many children began work well before the age of 10 and a minimum school leaving age—15 years—was not introduced in the UK until 1944. By the end of the century this has increased to 16 years with many children continuing school education until they were 18. As the length and scope of education advanced, adolescence became an increasingly important area of study.

Although the age range covered by developmental psychology may have increased, the overarching aim of the subject has not fundamentally changed: This is to describe and explain the nature of developmental change from its starting point to its end point. As you will discover from this handbook, developmental psychology begins before birth with the growth of the foetus. It moves on to consider birth and infancy, passing through the preschool years and entry into school, and ending with the transitions from adolescence to adulthood. A fully rounded account of development will consider many interrelated aspects of developmental change including language and cognitive ability, motor skills, social and emotional development, and interaction with family members and peers.

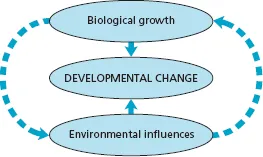

Scientific explanations of development have one central principle: Developmental changes occur both as a result of growth and through the interaction of the child with the environment. Characterising the dynamic principles that underlie growth, self-organisation and increasing complexity are of fundamental importance in developmental explanation. Development involves changes that occur over time yet, despite change, there is also stability and continuity with the past as new aspects of self, behaviour, and knowledge are formed. How new ways of acting and new knowledge emerge from the interaction between elements of earlier levels of understanding and new experience is of central concern to many developmental theories.

Two major strands of influence can be discerned in developmental psychology. These reflect a concern with growth, on the one hand, and with the impact of environmental influences on the other. Concerns with developmental growth take some of their inspiration from the biology of growth and evolution, whereas other aspects of explanation—those concerned with the impact of the environment on the child—consider the ways in which different cultures and different patterns of childhood experience channel development. From this dual perspective we can see that the explanation of human development requires us not only to understand human nature—because development is a natural phenomenon—but also to consider the diverse effects that a particular society and a particular set of experiences have upon the developing child. Development is as much a matter of the child acquiring a culture as it is a process of biological growth. Contemporary theories of development make the connection between nature and culture, albeit with varying emphases and, of course, with various degrees of success.

In a recent review, Cairns (1998) argues that the biological roots of developmental psychology are the strongest. He identifies two core ideas in 19th-century biology that shaped the newly emerging science of developmental psychology. These are the developmental principle outlined by Karl Ernst von Baer (1792–1876) and the evolutionary theory of Charles Darwin (1809–1882).

The central principle of developmental psychology

Developmental change results from an interaction between biology (“nature”) and experience (“nurture”). However, the interaction is a complex one because environmental factors can directly influence biological growth (e.g. brain growth) and genetic factors can influence the child's environment (e.g. a sociable child producing different reactions from others than an antisocial child).

The developmental principle

Von Baer, whose work is relatively unknown today to developmental psychologists, was a pioneer of comparative embryology. He was born in Estonia, where he began his career as a biologist. Later he moved to Russia before returning to Estonia at the end of his career.

Von Baer proposed that development proceeds in successive stages, from the more general to the more specific and from an initial state of relative homogeneity to one of increasing differentiation (Cairns, 1998). Von Baer's view of development was revolutionary when it was first advanced even though the notion of successive stages is widely accepted within modern developmental psychology. In order to understand the revolutionary nature of his views we need to understand the prevailing view of development that von Baer rejected.

When von Baer began his research, preformationism was part of the accepted view of development. In essence, preformationism claims that developmental transformations (such as those observed in the embryo) are illusory because the essential characteristics of an individual are fully predetermined at the outset of development. What changes is the size and interrelation of parts within an organism but the essential properties are preset and predetermined. In other words, according to preformationism, development fails to bring about any new or novel properties. On this view, the course of development through childhood and into adulthood is fully specified at birth.

An alternative to preformationism in the 19th century was recapitulationism. The essential idea behind recapitulationism is that, in the embryonic period, organisms pass through the adult form of all species from which they have evolved (see Figure 1.1). Haeckel famously captured the essence of recapitulationism as “ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny”, that is, the development of the individual re-enacts the development of the species. On this view, embryonic development could be seen as a “fast-forward replay of evolutionary history” (Cairns, 1998). Such a view inevitably leads to the conclusion that novel features can only be added in the terminal phase of development—what Haeckel (1874/1906) labelled the “biogenetic law”.

Von Baer rejected both preformationism and recapitulationism. He showed, in his own research on embryological development in different species, that the embryos of related species are very similar to one another in their early stages of development as Haeckel had demonstrated (see Figure 1.1). However, von Baer found on closer observation that there were species-typical differences early in the course of development as well as in the final stages. (See Chapter 4, Development from Conception to Birth, for evidence about the early development of the human embryo.) Von Baer thus saw development as a continuing process of differentiation of organisation in which novel developments could occur at any point in development—on this basis he rejected Haeckel's biogenetic law.

Preformationism

The essential characteristics of an organism are fully determined at the onset of development.

Observed developmental transformations are illusory.

The only real changes are the size and inter-relation of the parts within the organism.

Development fails to bring about novel properties.

Development follows a predetermined course.

Recapitulationism

The development of the individual re-enacts the development of the species.

During the embryonic period organisms pass through the adult form of the species from which they evolved.

Novel features can only be added in the last phase of development.

KEY TERMS

Preformationism: The now discredited theory of develo...