![]()

1 Introduction

Contents

Preliminaries

Levels of a Cognitive Theory

Marr's System of Levels

Chomsky's Competence and Performance

Pylyshyn's Distinction Between Algorithm and Functional Architecture

McClelland and Rumelhart's PDP Level

Newell's Knowledge Level and the Principle of Rationality

Current Formulation of the Levels Issue

The Algorithm Level

Behavioral Data

The Rational Level

The New Theoretical Framework

Lack of Identifiability at the Implementation Level

The Principle of Rationality

Applying the Principle of Rationality

Advantages of Rational Theory

Is Human Cognition Rational?

Computational Cost

Is there an Adaptive Cost?

Heuristics Need to be Evaluated in Terms of Expected Value

Applications of Normative Models Often Treat Uncertain Information as Certain

The Situation Assumed is not the Environment of Adaptation

Conclusions

The Rest of the Book

Appendix: Non-Identifiability and Response Time

PRELIMINARIES

A person writes a research monograph such as this with the intention that it will be read. As a consumer of such monographs, I know it is not an easy decision to invest the time in reading and understanding one. Therefore, it is important to be up front about what this book has to offer. In a few words, this book describes a new methodology for doing research in cognitive psychology and applies it to produce some important developments. The new methodology is important, because it offers the promise of rapid progress on some of the agenda of cognitive psychology. This methodology concentrates on the adaptive character of cognition, in contrast to the typical emphasis on the mechanisms underlying cognition.

I have been associated with a number of theoretical monographs (Anderson, 1976, 1983; Anderson & Bower, 1973). The sustaining question in this succession of theories has been the nature of human knowledge. The 1973 book was an attempt to take human memory tradition as it had evolved in experimental psychology and use the new insights of artificial intelligence to relate the ideas of this tradition to fundamental issues of human knowledge. The theory developed in that book was called HAM, a propositional network theory of human memory. The 1976 book was largely motivated by the pressing need to make a distinction between procedural and declarative knowledge. This distinction was absent in the earlier book and in the then-current literature on human memory. The theory developed in that book was called ACT. In ACT, declarative knowledge was represented in a propositional network and procedural knowledge in a production system. The 1983 book was motivated both by breakthroughs in developing a learning theory that accounts for the acquisition of procedural knowledge and in identifying a neurally plausible basis for the overall implementation of the theory. It was called ACT* to denote that it was a completion of the theoretical development begun in the previous book.

In the 1983 book on the ACT* theory, I tried to characterize its relationship to the ACT series of theories and my future plans for research: “… my plan for future research is to try to apply this theory wide and far, to eventually gather enough evidence to permanently break the theory and to develop a better one. In its present stage of maturity the theory can be broadly applied, and such broad application has a good chance of uncovering fundamental flaws” (Anderson, 1983, p. 19).

My method of applying the theory has been to use it as a basis for detailed studies of knowledge acquisition in a number of well-defined domains such as high-school mathematics and college-level programming courses. In these studies, we have been concerned with how substantial bodies of knowledge are both acquired and evolve to the point where the learner has a very powerful set of problem-solving skills in the domain (Anderson, Boyle, Corbett, & Lewis, in press; Anderson, Boyle, & Reiser, 1985; Anderson, Conrad, & Corbett; in press).

The outcome of this research effort has certainly not been what I expected. Despite efforts to prove the theory wrong (I even created a new production system, called PUPS for Penultimate Production System, to replace ACT*—Anderson & Thompson, 1989), I failed to really shake the old theory. As I have written elsewhere (Anderson, 1987c; Anderson, Conrad, & Corbett, in press), we have been truly surprised by the success of the ACT* theory in dealing with the data we have acquired about complex skill acquisition with our intelligent tutors. ACT* proved not to be vulnerable to a frontal assault, in which its predictions about skill acquisition are compared to the data. This book contains some theoretical ideas that are rather different than ACT*, produced by the new methodology that the book describes. These ideas do not so much contradict ACT* as they address the subject of human cognition in a different way.

The A in ACT* stands for Adaptive, and this book results from an effort to think through what it might mean for human cognition to be adaptive. However, this book is not cast as an update on the ACT* theory, but rather is an effort to develop some points about human cognition from an adaptive perspective. The majority of the book, the next four chapters, tries to develop theory from an adaptive perspective in four related fields of cognition. This chapter is devoted to setting the stage for that development.

To state up front where this chapter is going, the argument is that we can understand a lot about human cognition without considering in detail what is inside the human head. Rather, we can look in detail at what is outside the human head and try to determine what would be optimal behavior given the structure of the environment and the goals of the human. The claim is that we can predict behavior of humans by assuming that they will do what is optimal. This is a different level of analysis than the analysis of mental mechanisms that has dominated information-processing psychology. Having raised the possibility of levels of analysis, the questions arise as to just how many levels there are and why we would want to pursue one level rather than another. It turns out that there have been many ideas expressed on these topics in cognitive science. Rather than just present my position on this and pretend to have invented the wheel, it is appropriate to review the various positions and their interrelationships. However, if the reader is impatient with such discussion, it is possible to skip to the section in the chapter that presents “The New Theoretical Framework,” where the discussion of rational analysis begins.

LEVELS OF A COGNITIVE THEORY

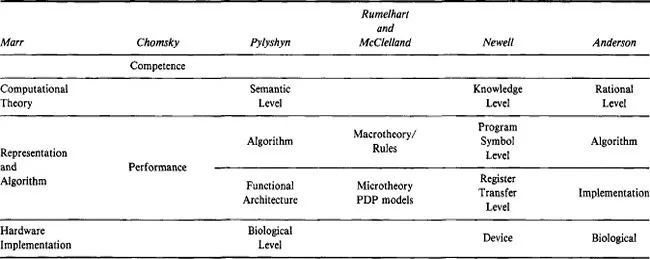

Table 1-1 is a reference for this section, in that it tries to relate the terminology of various writers. I start with the analysis of David Marr, which I have found to be particularly influential.

Marr's System of Levels

No sooner had I sent in the final draft of the ACT* book to the publisher than I turned to reading the recently published book by Marr (1982) on vision. It contained a very compelling argument about how to do theory development. I read over and over again his prescription for how to proceed in developing a theory:

TABLE 1-1

Levels of Cognitive Theory According to Various Cognitive Scientists

We can summarize our discussion in something like the manner shown in Figure 1-4 [our Table 1-2], which illustrates the different levels at which an information-processing device must be understood before one can be said to have understood it completely. At one extreme, the top level, is the abstract computational theory of the device, in which the performance of the device is characterized as a mapping from one kind of information to another, the abstract properties of this mapping are defined precisely, and its appropriateness and adequacy for the task at hand are demonstrated. In the center is the choice of representation for the input and output and the algorithm to be used to transform one into the other. And at the other extreme are the details of how the algorithm and representation are realized physically—the detailed computer architecture, so to speak. These three levels are coupled, but only loosely. The choice of an algorithm is influenced, for example, by what it has to do and by the hardware in which it must run. But there is a wide choice available at each level, and the explication of each level involves issues that are rather independent of the other two (pp. 24-25).

Although algorithms and mechanisms are empirically more accessible, it is the top level, the level of computational theory, which is critically important from an information-processing point of view. The reason for this is that the nature of the computations that underlie perception depends more upon the computational problems that have to be solved than upon the particular hardware in which their solutions are implemented. To phrase the matter another way, an algorithm is likely to be understood more readily by understanding the nature of the problem being solved than by examining the mechanism (and the hardware) in which it is embodied.

In a similar vein, trying to understand perception by studying only neurons is like trying to understand bird flight by studying only feathers: It just cannot be done. In order to understand bird flight, we have to understand aerodynamics; only then do the structure of feathers and the different shapes of birds’ wings make sense. More to the point, as we shall see, we cannot understand why retinal ganglion cells and lateral geniculate neurons have the receptive fields they do just by studying their anatomy and physiology. We can understand how these cells and neurons behave as they do by studying their wiring and interactions, but in order to understand why the receptive fields are as they are—why they are circularly symmetrical and why their excitatory and inhibitory regions have characteristic shapes and distributions—we have to know a little of the theory of differential operators, band-pass channels, and the mathematics of the uncertainty principle (pp. 27-28).

TABLE 1-2

Marr's Description of the Three Levels at Which Any Machine Carrying out an Information-Processing Task Must be Understood

| Computational Theory | Representation and Algorithm | Hardware Implementation |

| What is the goal of the computation, why is it appropriate, and what is the logic of the strategy by which it can be carried out? | How can this computational theory be implemented? In particular, what is the representation for the input and output, and what is the algorithm for the transformation? | How can the representation and algorithm be realized physically? |

Marr's terminology of “computational theory” is confusing and certainly did not help me appreciate his points. (Others have also found this terminology inappropriate—e.g., Arbib, 1987). His level of computational theory is not really about computation but rather about the goals of the computation. His basic point is that one should state these goals and understand their implications before one worries about their computation, which is really the concern of the lower levels of his theory.

Marr's levels can be understood with respect to stereopsis. At the computational level, there is the issue of how the pattern of light on each retina enables inferences about depth. The issue here is not how it is done, but what should be done. What external situations are likely to have given rise to the retinal patterns? Once one has a theory of this, one can then move to the level of representation and algorithm and specify a procedure for actually extracting the depth information. Having done this, one can finally inquire as to how this procedure is implemented in the hardware of the visual system.

Marr compared his computational theory to Gibson's (1966) ecological optics. Gibson claimed that there were certain properties of the stimulus which would invariantly signal features in the external world. In his terminology, the nervous system “resonates” to these invariants. Marr credited Gibson with recognizing that the critical question is to identify what in the stimulus array signals what in the real world. However, he criticized Gibson for not recognizing that, in answering this question, it is essential to precisely specify what that relationship is. The need for precision is apparent to someone, like Marr, working on computer vision. This need was not apparent to Gibson (see Shepard, 1984, for an extensive analysis of Gibson's theory).

I tried to see how to apply Marr's basic admonition to my own concern, which was higher-level cognition, but it just did not seem to apply. Although Marr's prescription seemed fine for vision, it seemed that the representation and algorithm level was the fundamental level for the study of human cognition. It was certainly the level that information-processing psychology had progressed along for the last 30 years.

What I initially failed to focus on was the essential but unstated adaptionist principle in Marr's argument. Vision could be understood by studying a problem only if (a) we assumed that vision was a solution to that problem, (b) we assumed that the solution to that problem was largely unique, and (c) we assumed that something forced vision to adopt that solution. For instance, in the case of stereopsis, we had to assume that vision solved the problem of extracting the three-dimensional structure from two two-dimensional arrays, and there was usually a single best interpretation of two two-dimensional arrays. Analysis of the visual environment of humans suggests that there is usually a best interpretation. To pursue Marr's agenda, it is not enough to argue that there is a unique best solution; we also have to believe that there are adaptive forces that created a visual system that would deliver this best solution. Perhaps other aspects of cognition deal with problems that have best solutions, and the organism is similarly adapted to achieve these best solutions. Once I cast what Marr was doing in these terms, I saw the relevance of his arguments to cognition in general.

Marr's hardware-implementation level may still be inapplicable to the study of cognition. It made sense in the case of vision, where the physiology is reasonably well understood. However, the details of the physical base of cognition are still unclear.

Marr's analysis of these levels is very much motivated by the issue of how to make progress in cognitive science. As he saw it, the key to progress is to start off at the level of computational theory. As he bemoaned about the practice of theory in vision:

For far too long, a heuristic program for carrying out some task was held to be a theory of that task, and the distinction between what a program did and how it did it was not taken seriously. As a result, (1) a style of explanation evolved that invoked the use of special mechanisms to solve particular problems, (2) particular data structures, such as the lists of attribute value pairs called property lists in the LISP programming language, were held to amount to theories of the representation of knowledge, and (3) there was frequently no way to determine whether a program would deal with a particular case other than by running the program. (Marr, 1982, p. 28)

These problems certainly characterize the human information-processing approach to higher level cognition. We pull out of an infinite grab bag of mechanisms, bizarre creations whose only justification is that they predict the phenomena in a class of experiments. These mechanisms are becoming increasingly complex, and we wind up simulating them and trying to understand their behavior just as we try to understand the human. We almost never ask the question of why these mechanisms compute in the way they do.

Chomsky's Competence and Performance

Marr related his distinction to Chomsky's much earlier distinction between competence and performance in linguistics, identifying his computational theory with Chomsky's competence component. As Chomsky (1965) described the distinction:

Linguistic theory is concerned primarily with an ideal speaker-listener, in a completely homogeneous speech-community, who knows its language perfectly and is unaffected by such grammatically irrelevant conditions as memory limitations, distractions, shifts of attention and interest, and errors (random or characteristic) in applying his knowledge of the language in actual performance. This seems to me to have been the position of the founders of modern general linguistics, and no cogent reason for modifying it has been offered. To study actual linguistic performance, we must consider the interaction of a variety of factors, of which the underlying competence of the speaker-hearer is only one. In this respect, study of language is no different from empirical investigation of other complex phenomena.

We thus make a fundamental distinction between competence (the speaker-hearer's knowledge of his language) and performance (the actual use of language in concrete situations). Only under the idealization set forth in the preceding paragraph is performance a direct reflection of competence. In actual fact, it obviously could not directly reflect competence. A record of natural speech will show numerous false starts, deviations from rules, changes of plan in mid-course, and so on. The problem for the linguist, as well as for the child learning the language, is to determine from the data of performance the underlying system of rules that has been mastered by the speaker-hearer and that he puts to use in actual performance. (pp...