eBook - ePub

Psychosocial Treatments

- 192 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Psychosocial Treatments

About this book

The editors of this volume have assembled recent articles discussing elements of each of the several commonly used psychosocial interventions -- including relapse prevention therapy, community reinforcement, voucher-based programs, self-help therapies, and motivational enhancement therapy--in addition to research-based articles that demonstrate the efficacy of these approaches. The selections in this book will provide the reader with a broad overview of the field as well as the specific information needed to use these therapies in a variety of clinical settings.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Psychosocial Treatments by Elinore McCance-Katz, H. Westley Clark, Elinore McCance-Katz,H. Westley Clark in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psicologia & Dipendenze in psicologia. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Relapse Prevention An Overview of Marlatt’s Cognitive-Behavioral Model

Mary E.Larimer, Ph.D.

Rebekka S.Palmer

G.Alan Marlatt, Ph.D.

Relapse prevention (RP) is an important component of alcoholism treatment. The RP model proposed by Marlatt and Gordon suggests that both immediate determinants (e.g., high-risk situations, coping skills, outcome expectancies, and the abstinence violation effect) and covert antecedents (e.g., lifestyle factors and urges and cravings) can contribute to relapse. The RP model also incorporates numerous specific and global intervention strategies that allow therapist and client to address each step of the relapse process. Specific interventions include identifying specific high-risk situations for each client and enhancing the client’s skills for coping with those situations, increasing the client’s self-efficacy, eliminating myths regarding alcohol’s effects, managing lapses, and restructuring the client’s perceptions of the relapse process. Global strategies comprise balancing the client’s lifestyle and helping him or her develop positive addictions, employing stimulus control techniques and urge-management techniques, and developing relapse road maps. Several studies have provided theoretical and practical support for the RP model.

Keywords: AODD (alcohol and other drug dependence) relapse; relapse prevention; treatment model; cognitive therapy; behavior therapy; risk factors;coping skills; self-efficacy; expectancy; AOD (alcohol and other drug) abstinence; lifestyle; AOD craving; intervention; alcohol cue; reliability (research methods); validity (research methods); literature review

Relapse, or the return to heavy alcohol use following a period of abstinence or moderate use, occurs in many drinkers who have undergone alcoholism treatment. Traditional alcoholism treatment approaches often conceptualize relapse as an end-state, a negative outcome equivalent to treatment failure. Thus, this perspective considers only a dichotomous treatment outcome—that is, a person is either abstinent or relapsed. In contrast, several models of relapse that are based on social-cognitive or behavioral theories emphasize relapse as a transitional process, a series of events that unfold over time (Annis, 1986; Litman et al., 1979; Marlatt & Gordon, 1985). According to these models, the relapse process begins prior to the first post-treatment alcohol use and continues after the initial use. This conceptualization provides a broader conceptual framework for intervening in the relapse process to prevent or reduce relapse episodes and thereby improve treatment outcome.

This article presents one influential model of the antecedents of relapse and the treatment measures that can be taken to prevent or limit relapse after treatment completion. This relapse prevention (RP) model, which was developed by Marlatt and Gordon (1985) and which has been widely used in recent years, has been the focus of considerable research. This article reviews various immediate and covert triggers of relapse proposed by the RP model, as well as numerous specific and general intervention strategies that may help patients avoid and cope with relapse-inducing situations. The article also presents studies that have provided support for the validity of the RP model.

OVERVIEW OF THE RP MODEL

Marlatt and Gordon’s (1985) RP model is based on social-cognitive psychology and incorporates both a conceptual model of relapse and a set of cognitive and behavioral strategies to prevent or limit relapse episodes (for a detailed description of the development, theoretical underpinnings, and treatment components of the RP model, see Dimeff & Marlatt, 1998; Marlatt, 1996; Marlatt & Gordon, 1985). A central aspect of the model is the detailed classification (i.e., taxonomy) of factors or situations that can precipitate or contribute to relapse episodes. In general, the RP model posits that those factors fall into two categories: immediate determinants (e.g., high-risk situations, a person’s coping skills, outcome expectancies, and the abstinence violation effect) and covert antecedents (e.g., lifestyle imbalances and urges and cravings).

Treatment approaches based on the RP model begin with an assessment of the environmental and emotional characteristics of situations that are potentially associated with relapse (i.e., high-risk situations). After identifying those charac teristics, the therapist works forward by analyzing the individual drinker’s response to these situations, as well as backward to examine the lifestyle factors that increase the drinker’s exposure to high-risk situations. Based on this careful examination of the relapse process, the therapist then devises strategies to target weaknesses in the client’s cognitive and behavioral repertoire and thereby reduce the risk of relapse.

Immediate Determinants of Relapse

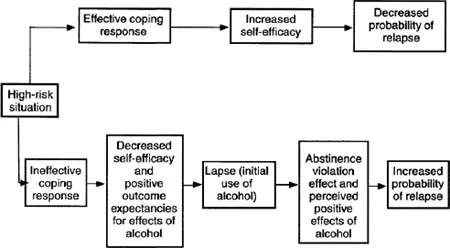

High-Risk Situations. A central concept of the RP model postulates that high-risk situations frequently serve as the immediate precipitators of initial alcohol use after abstinence (see Figure 1.1). According to the model, a person who has initiated a behavior change, such as alcohol abstinence, should begin experiencing increased self-efficacy or mastery over his or her behavior, which should grow as he or she continues to maintain the change. Certain situations or events, however, can pose a threat to the person’s sense of control and, consequently, precipitate a relapse crisis. Based on research on precipitants of relapse in alcoholics who had received inpatient treatment, Marlatt (1996) categorized the emotional, environmental, and interpersonal characteristics of relapse-inducing situations described by study participants. According to this taxonomy, several types of situations can play a role in relapse episodes, as follows:

• Negative emotional states, such as anger, anxiety, depression, frustration, and boredom, which are also referred to as intrapersonal high-risk situations, are associated with the highest rate of relapse (Marlatt & Gordon, 1985). These emotional states may be caused by primarily intrapersonal perceptions of certain situations (e.g., feeling bored or lonely after coming home from work to an empty house) or by reactions to environmental events (e.g., feeling angry about an impending layoff at work).

• Situations that involve another person or a group of people (i.e., interpersonal high-risk situations), particularly interpersonal conflict (e.g., an argument with a family member), also result in negative emotions and can precipitate relapse. In fact, intrapersonal negative emotional states and interpersonal conflict situations served as triggers for more than one-half of all relapse episodes in Marlatt’s (1996) analysis.

• Social pressure, including both direct verbal or nonverbal persuasion and indirect pressure (e.g., being around other people who are drinking), contributed to more than 20 percent of relapse episodes in Marlatt’s (1996) study.

• Positive emotional states (e.g., celebrations), exposure to alcohol-related stimuli or cues (e.g., seeing an advertisement for an alcoholic beverage or passing by one’s favorite bar), testing one’s personal control (i.e., using“willpower” to limit consumption), and nonspecific cravings also were identified as high-risk situations that could precipitate relapse.

Coping. Although the RP model considers the high-risk situation the immediate relapse trigger, it is actually the person’s response to the situation that determines whether he or she will experience a lapse (i.e., begin using alcohol). A person’s coping behavior in a high-risk situation is a particularly critical determinant of the likely outcome. Thus, a person who can execute effective coping strategies (e.g., a behavioral strategy, such as leaving the situation, or a cognitive strategy, such as positive self-talk) is less likely to relapse compared with a person lacking those skills. Moreover, people who have coped successfully with high-risk situations are assumed to experience a heightened sense of self-efficacy (i.e., a personal perception of mastery over the specific risky situation) (Bandura, 1977; Marlatt et al., 1995, 1999; Marlatt & Gordon, 1985). Conversely, people with low self-efficacy perceive themselves as lacking the motivation or ability to resist drinking in high-risk situations.

FIGURE 1.1. The cognitive-behavioral model of the relapse process posits a central role for high-risk situations and for the drinker’s response to those situations. People with effective coping responses have confidence that they can cope with the situation (i.e., increased self-efficacy), thereby reducing the probability of a relapse. Conversely, people with ineffective coping responses will experience decreased self-efficacy, which, together with the expectation that alcohol use will have a positive effect (i.e., positive outcome expectancies), can result in an initial lapse. This lapse, in turn, can result in feelings of guilt and failure (i.e., an abstinence violation effect). The abstinence violation effect, along with positive outcome expectancies, can increase the probability of a relapse.

NOTE: This model also applies to users of drugs other than alcohol.

Outcome Expectancies. Research among college students has shown that those who drink the most tend to have higher expectations regarding the positive effects of alcohol (i.e., outcome expectancies) and may anticipate only the immediate positive effects while ignoring or discounting the potential negative consequences of excessive drinking (Carey, 1995). Such positive outcome expectancies may become particularly salient in high-risk situations, when the person expects alcohol use to help him or her cope with negative emotions or conflict (i.e., when drinking serves as“self-medication”). In these situations, the drinker focuses primarily on the anticipation of immediate gratification, such as stress reduction, neglecting possible delayed negative consequences.

The Abstinence Violation Effect. A critical difference exists between the first violation of the abstinence goal (i.e., an initial lapse) and a return to uncontrolled drinking or abandonment of the abstinence goal (i.e., a full-blown relapse). Although research with various addictive behaviors has indicated that a lapse greatly increases the risk of eventual relapse, the progression from lapse to relapse is not inevitable.

Marlatt and Gordon (1980, 1985) have described a type of reaction by the drinker to a lapse called the abstinence violation effect, which may influence whether a lapse leads to relapse. This reaction focuses on the drinker’s emotional response to an initial lapse and on the causes to which he or she attributes the lapse. People who attribute the lapse to their own personal failure are likely to experience guilt and negative emotions that can, in turn, lead to increased drinking as a further attempt to avoid or escape the feelings of guilt or failure. Furthermore, people who attribute the lapse to stable, global, internal factors beyond their control (e.g.,“I have no willpower and will never be able to stop drinking”) are more likely to abandon the abstinence attempt (and experience a full-blown relapse) than are people who attribute the lapse to their inability to cope effectively with a specific high-risk situation. In contrast to the former group of people, the latter group realizes that one needs to“learn from one’s mistakes” and, thus, they may develop more effective ways to cope with similar trigger situations in the future.

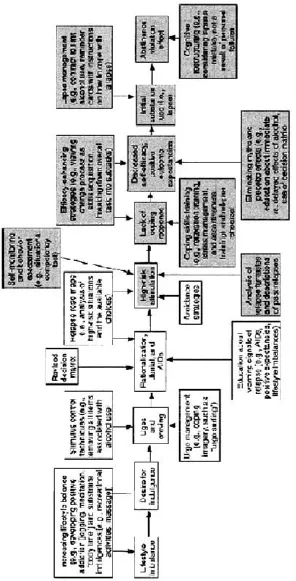

Covert Antecedents of High-Risk Situations

Although high-risk situations can be conceptualized as the immediate determinants of relapse episodes, a number of less obvious factors also influence the relapse process. These covert antecedents include lifestyle factors, such as overall stress level, as well as cognitive factors that may serve to“set up” a relapse, such as rationalization, denial, and a desire for immediate gratification (i.e., urges and cravings) (see Figure 1.2). These factors can increase a person’s vulnerability to relapse both by increasing his or her exposure to high-risk situations and by decreasing motivation to resist drinking in high-risk situations.

In many cases, initial lapses occur in high-risk situations that are completely unexpected and for which the drinker is often unprepared. In relapse“setups,” however, it may be possible to identify a series of covert decisions or choices, each of them seemingly inconsequential, which in combination set the person up for situations with overwhelmingly high risk. These choices have been termed“apparently irrelevant decisions” (AIDs), because they may not be overtly recog nized as related to relapse but nevertheless help move the person closer to the brink of relapse. One example of such an AID is the decision by an abstinent drinker to purchase a bottle of liquor“just in case guests stop by.” Marlatt and Gordon (1985) have hypothesized that such decisions may enable a person to experience the immediate positive effects of drinking while disavowing personal responsibility for the lapse episode (“How could anyone expect me not to drink when there’s a bottle of liquor in the house?”).

Lifestyle Factors. Marlatt and Gordon (1985) have proposed that the covert antecedent most strongly related to relapse risk involves the degree of balance in the person’s life between perceived external demands (i.e.,“shoulds”) and internally fulfilling or enjoyable activities (i.e.,“wants”). A person whose life is full of demands may experience a constant sense of stress, which not only can generate negative emotional states, thereby creating high-risk situations, but also enhances the person’s desire for pleasure and his or her rationalization that indulgence is justified (“I owe myself a drink”). In the absence of other non-drinking pleasurable activities, the person may view drinking as the only means of obtaining pleasure or escaping pain.

FIGURE 1.2 Covert antecedents and immediate determinants of relapse and intervention strategies for identifying and preventing or avoiding those determinants. Lifestyle balance is an important aspect of preventing relapse. If stressors are not balanced by sufficient stress management strategies, the client is more likely to use alcohol in an attempt to gain some relief or escape from stress. This reaction typically leads to a desire for indulgence that often develops into cravings and urges. Two cognitive mechanisms that contribute to the covert planning of a relapse episode — rationalization and denial—as well as apparently irrelevant decisions (AIDs) can help precipitate high-risk situations, which are the central determinants of a relapse. People who lack adequate coping skills for handling these situations experience reduced confidence in their ability to cope (i.e., decreased self-efficacy). Moreover, these people often have positive expectations regarding the effects of alcohol (i.e., outcome expectancies). These factors can lead to initial alcohol use (i.e., a lapse), which can induce an abstinence violation effect that, in turn, influences the risk of progressing to a full relapse. Self-monitoring, behavior assessment, analyses of relapse fantasies, and descriptions of past relapses can help identify a person’s high-risk situations. Specific intervention strategies (e.g., skills training, relapse rehearsal, education, and cognitive restructuring) and general strategies (e.g., relaxation...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Psychosocial Treatments

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Series Introduction

- Introduction

- 1. Relapse Prevention: An Overview of Marlatt’s Cognitive-Behavioral Model

- 2. Motivational Interviewing

- 3. Motivational Interviewing to Enhance Treatment Initiation in Substance Abusers: An Effectiveness Study

- 4. Network Therapy for Cocaine Abuse: Use of Family and Peer Support

- 5. The Community-Reinforcement Approach

- 6. Voucher-Based Incentives: A Substance Abuse Treatment Innovation

- 7. A Comparison of Contingency Management and Cognitive-Behavioral Approaches During Methadone Maintenance Treatment for Cocaine Dependence

- 8. Self-Help Strategies Among Patients with Substance Use Disorders

- 9. Residential Treatment for Dually Diagnosed Homeless Veterans: A Comparison of Program Types

- 10. Psychotherapies for Adolescent Substance Abusers: 15-Month Follow-Up of a Pilot Study

- 11. The Links Between Alcohol, Crime and the Criminal Justice System: Explanations, Evidence and Interventions

- Permission Acknowledgments

- Index