![]()

1

Rotations and Circumductions

Jean Piaget

with

CI. Monnier

and

J. Vauclair

Chapters 2 and 3 have to do with morphisms linked to rotations of varying degree and complexity. In chapter 2, the rotations involve cyclic successions of several elements; in chapter 3, they involve rotations of a cube. It makes sense, therefore, to begin with the simplest situation where the positions of a single object, for example, the head and feet of a doll, vary according to the rotations and circumductions to which they are subjected and where morphisms consist only in linking starting to ending points by means of transformations.

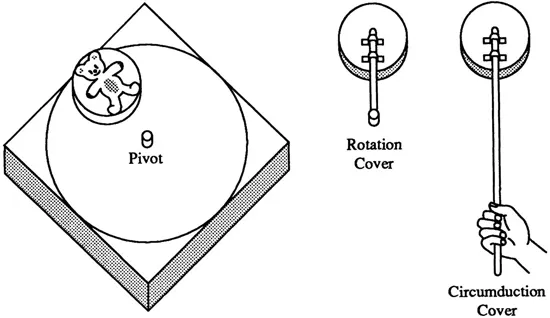

1. Technique

The horizontal apparatus consists of a square platform on which is drawn a large circle almost tangent to the edges (Fig. 1.1). On the platform sits a round box containing an unmovable bear lying on its back. The child is asked to indicate the bear’s head and hind legs. The box is then closed by means of lids of which there are two sorts. One is attached to a long stick that allows the box to be pushed around the circumference of the circle without changing the bear’s orientation relative to the subject (circumduction); the other has a shorter stick that attaches to a pivot in center of the circle so that, when the box is pushed around the circle, the bear’s orientation rotates from rightside-up through upside-down and back to rightside-up relative to the subject (rotation). In both cases, the investigator has the child establish the position of the head at the start, for example, toward the subject, toward the window, and so forth. Then the box is closed, and the child is asked to move the box 90°, 180°, or 270° using specific movements of the stick and to indicate the position of the bear after the movement is performed.

Fig. 1.1. Horizontal apparatus.

The vertical apparatus consists of a little trolley car on rails (Fig. 1.2). On it sits a wooden base holding a picture of a little man drawn on a card. The picture is masked while the investigator performs movements either of circumduction (where the man remains upright) or rotation (where the man turns upside-down at 180° and rightside-up at 360°. After each movement, the experimenter asks the subject whether the man is standing, lying down, and so on, and in what direction his head is pointing as well as to give reasons for his answers. Then the investigator takes the card out of the base, hands it to the child, and asks him, by imitating the movements, to anticipate the path to be traversed or to reproduce the path that has been traversed when the little man was behind the screen. The child also is asked to compare the two apparatuses.

Fig. 1.2. Vertical apparatus.

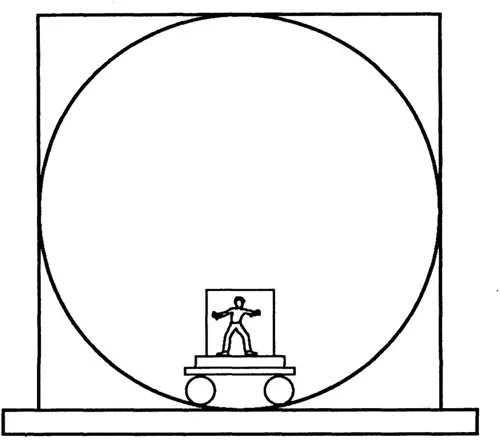

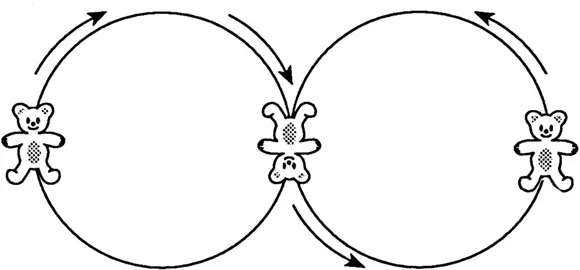

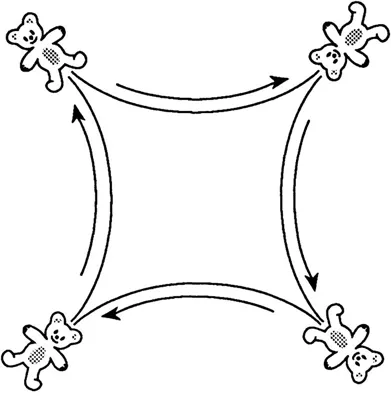

Two other horizontal patterns of movement also are used (

Fig. 1.3). One is a figure eight (∞) on which different paths, for example,

,

, and so forth are followed. The other is a figure made of four 90° arcs of a circle turned inward with the points of contact extended, for example,

. With the latter figure, the bear’s head is oriented toward the outside at the starting point to which it subsequently returns.

1 Fig. 1.3. Horizontal figure eight apparatus.

Finally, let us note that in each situation, orbital rotations can be combined with rotations proper, that is, rotations in place making an object turn on itself. Or subjects even may be asked to perform compositions such as an orbital rotation of 120° plus a rotation in place which compensates for it, all of which adds up to a circumduction.

2. Elementary or “Intramorphic” Correspondences

The aim of this work being to study the progressive composition of correspondences, it makes sense to begin by examining those that do not seem to be composed with one another.

Fig. 1.4. Inverted arcs of a circle apparatus.

VAL (3 years): VAL is shown that, at the start, the bear’s head lies in the direction the stick is pointing (horizontal apparatus).2 After a 90° rotation, she wrongly indicates the opposite of the bear’s true orientation, then corrects her answer, then changes back to the incorrect response. By contrast, after a 180° rotation she understands right away (“Toward me, upside down”), but she does not succeed, that is, does not compose the symmetrical of this symmetry, when the box is rotated the other 180° back to the starting point. In the case of circumduction, she likewise believes that 180° brings about an inversion (“Toward me”) and fails for other positions.

TIE (4 years, 1 month): After several tries with the the bear visible, TIE succeeds in answering all questions about circumduction on the horizontal apparatus. However, except for 180° he fails on questions about rotation. In the latter case, he turns himself from the bottom to the top of the circle (by moving around the table from 6 to 12 o’clock) and then, starting at 270°, he walks the stick around to 90° in order to find the symmetry. Reinterrogated at 4 years, 5 months, he begins, for rotations, as he had 4 months previously, but subsequently succeeds for 90° because “he had his head there under the board” (stick). In other words, he does so by using the stick as a reference without, for all that, understanding the rotation (failure for a 180° rotation starting from the left-right position). By contrast, he now fails on all problems relative to circumduction, except at 180°.

OLI (4 years, 4 months): On the vertical apparatus, OLI succeeds on questions relative to circumduction and rotation to 180°. However, he believes that at 90° and 270°, the “little fellow always looks like he’s lying down.” With respect to the position of the head on the horizontal apparatus, he says that “if you put him like that (90°), the head’s there.”—“What helps you?”—“The stick.” For a rotation of 180° on the vertical apparatus, “he’s upside-down,” whereas for circumduction, that is not the case because “I held the stick straight.” The difference is that “sometimes you can make the little fellow turn on himself.” After this false prediction for 90° because “before his head was there,” he sees his error, but makes in-place rotations to make things come out alright.

FLO (4 years, 6 months): Starting with circumduction on the horizontal apparatus, FLO makes an error for 180°because “you’ve changed sides, and so the head’s changed sides.” Then, after moving on to rotations, she again makes errors for 180° as if there were circumduction and only succeeds for 180° after several tries at 90°, and so on.

MIC (4 years, 7 months): After succeeding on questions relative to 180° rotation on the horizontal apparatus, MIC at first makes mistakes on circumductions from 90° to 270° or from 0° to 180°. When he succeeds, he again is asked about rotation and mixes the two movements, first on movements from 0° to 90, then on others, and so forth.

CAR (5 years, 6 months): For 180° rotations on the vertical apparatus, CAR says, “He’s upside-down maybe, because you put him on the bottom.”—“And how was he before?”—“Not upside-down. You turned him, and he was put upside down.” For 90°, she predicts that the little man will be lying down, but she is not sure what side the head will be on. For 270°, “I think he’ll be upside down.” By contrast, she succeeds in reproducing the trajectory by following the circumference but thinks that the results change with the direction of movement. For circumduction, 180° first gives “upside down” but subsequently, “I think standing up also. You haven’t put him upside down.” Interestingly, however, when she is asked later to reproduce this circumduction, she does so as an orbital rotation of 180° followed by a rotation proper (in place) also of 180°. This gives an unintentional composition that would be intermorphic if it were programmed. As it is, only a simple correction is involved (cf. the end of OLI’s interrogation).

ARI (5 years, 4 months): ARI succeeds on circumductions with the vertical apparatus, responds correctly for rotations of 180° from top to bottom but hesitates for rotations in the opposite direction, and then constantly makes mistakes by mixing circumductions and rotations.

STE (5years, 11 months): After two errors, STE succeeds on circumductions as well as rotations of 180° but makes errors for movements from After two errors, STE succeeds on circumductions as well as rotations of 180° but makes errors for movements from left to right and for other positions as well. In the case of rotation, it is “the box” that moves, but in circumduction “nothing” moves.

It is a matter of course that predictions of the bear’s or little man’s positions in cyclic succession rest on cotransformational correspondences, because the relationship between one position and the following position results from a rotation. With that in mind, one general fact appears to dominate the preceding reactions. The orbital rotation described by the screened bear at the end of the stick is thought of in terms of rotation proper or, therefore, in terms of rotation in place. This erroneous assimilation of orbital rotation to in-place rotation is natural because, from the first sensorimotor stages, the child knows how to turn an object in place in order to look at its different sides or back, and for a long time he imagines every kind of rotation according to this model. In the case at hand, the subject sees the orbital rotation quite well and even executes it easily on the horizontal apparatus. He does not, however, put the positions into correspondence with the rotation as a whole but instead conceives them as resulting from in-place rotations. As OLI says, in order to differentiate orbital rotation from circumduction, “You can make the fellow turn on himself,” or as VAL, OLI, CAR, and so on, say, “He’s upside-down” (at 180°) and especially “you turned him, and he was put upside down.” OLI makes in-place rotations in order to correct his errors and CAR, in order to realize a rotation of 180°, completes a circumduction by making an in-place rotation at the end. STE says that the box moves during a rotation but that it does nothing during a circumduction. In this case, because he has just effected the movements himself, the “nothing” can only mean the absence of a rotation proper. Another index of this carelessness with regard to orbital rotation is that predictions at 90° are not easier than those at 270°, which would not be the case if the subject were trying to base his correspondences on perceptual pursuit of the circular trajectory.

The first consequence stemming from this essential fact is that, on the average, positions arrived at through circumduction are predicted better than those arrived at through orbital rotation. This is because there is isomorphism among all positions arrived at through circumduction and, therefore, little that is analogous to rotations proper. Even so, several subjects give in to the partial analogy resulting from the fact that the orbital trajectory is the same in both cases (notably for circumductions of 180°). For example, VAL and FLO say “you’ve changed sides, and so the head’s changed sides,” and CAR corrects herself by invoking an absence of rotation proper—“you haven’t put him upside down.”

This occasional contamination of circumduction by orbital rotation (doubtless because of insufficient interpretation) is observed as confusion between two kinds of correspondences. However, with TIE, OLI, and ARI, it appears after initial success with circumduction when questions of rotation are introduced. Only FLO presents this confusion starting with circumduction.

One fact that seems to confirm what has been said about orbital rotation being assimilated to rotation proper is that subjects 3 to 4 years old give better responses for rotations than 5-year-olds do. In effect, the younger subjects care nothing about the trajectory and base their answers on references such as (TIE) “his head there under the board” (indicating the end of the stick) or (OLI) “the little stick” that “helps.” Around 5 years of age, by contrast, there are attempts to take account of the orbital rotation as a trajectory (see CAR) but without yet being able to do so successfully for the reasons we have seen.

In sum, the correspondences these children succeed in creating are isomorphisms of position in the case of circumductions and inversions of 180° in top-to-bottom rotations where the precocious role of correspondences by symmetry is combined with interpretation in terms of rotation proper. However, none of these successes may yet be taken as evidence of compositions, because an isomorphism that is repeated cannot yet be qualified as such. Moreover, in the case of rotational inversions of 180°, the lack of composition is so serious that correct anticipation of rotations made in the top-to-bottom direction (from 12 to 6 o’clock) is not always accomp...