- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Mama Dada is the first book to examine Gertrude Stein's drama within the history of the theatrical and cinematic avant-gardes. Since the publication of Stein's major writings by the Library of America in 1998, interest in her dramatic writing has escalated, particularly in American avant-garde theaters. This book addresses the growing interest in Stein's theater by offering the first detailed analyses of her major plays, and by considering them within a larger history of avant-garde performance. In addition to comparing Stein's plays and theories to those generated by Dadaists, Surrealists, and Futurists, this study further explores the uniqueness of Stein via these theatrical movements, including discussions of her interest in American life and drama, which argues that a significant and heretofore unrecognized relationship exists among the histories of avant-garde drama, cinema, and homosexuality. By examining and explaining the relationship among these three histories, the dramatic writings of Stein can best be understood, not only as examples of literary modernism, but also as influential dramatic works that have had a lasting effect on the American theatrical avant-

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter 1

Introduction

"Supposing no one asked a question. What would be the answer."

Gertrude Stein, "Near East or Chicago"

"I am violently devoted to the new."

Gertrude Stein, Everybody's

Autobiography

Autobiography

Although Picasso's earlier painting Portrait of Gertrude Stein (1906) is better known, his later Homage à Gertrude Stein (1909) is the more prophetic of the two. The painting features several winged female figures bearing a still-life bowl of fruit and a trumpet. Picasso's honoring of Stein includes both the staples of figurative art, the fruit bowl and the female nude, and the classical image of the biblical herald—a winged figure with a trumpet. Picasso paints his version of Stein with visual references to painting's long history of biblical subjects (a style popular until the emergence of the Impressionists in the mid-nineteenth century). And yet, despite the references to classical figurative painting, the work is recognizable as an avant-garde painting. The bodies are disproportionate and abstracted; the color palette is muted and blurred with no discernible light source; and the relationship between the figures ambiguous. It is with this tension between the historical and the innovative, the figurative and the abstract, the classical and the modern, that Picasso honors Gertrude Stein. That he should also include a herald seems entirely appropriate, for while Stein embraced the past, she continually sought "the new." In her appreciation of art (as, arguably, the first great collector of modern painting with her brother Leo) and in her own artistic efforts, Stein foreshadowed much of the artistic progression of the twentieth century, though she would live to see less than half of it.

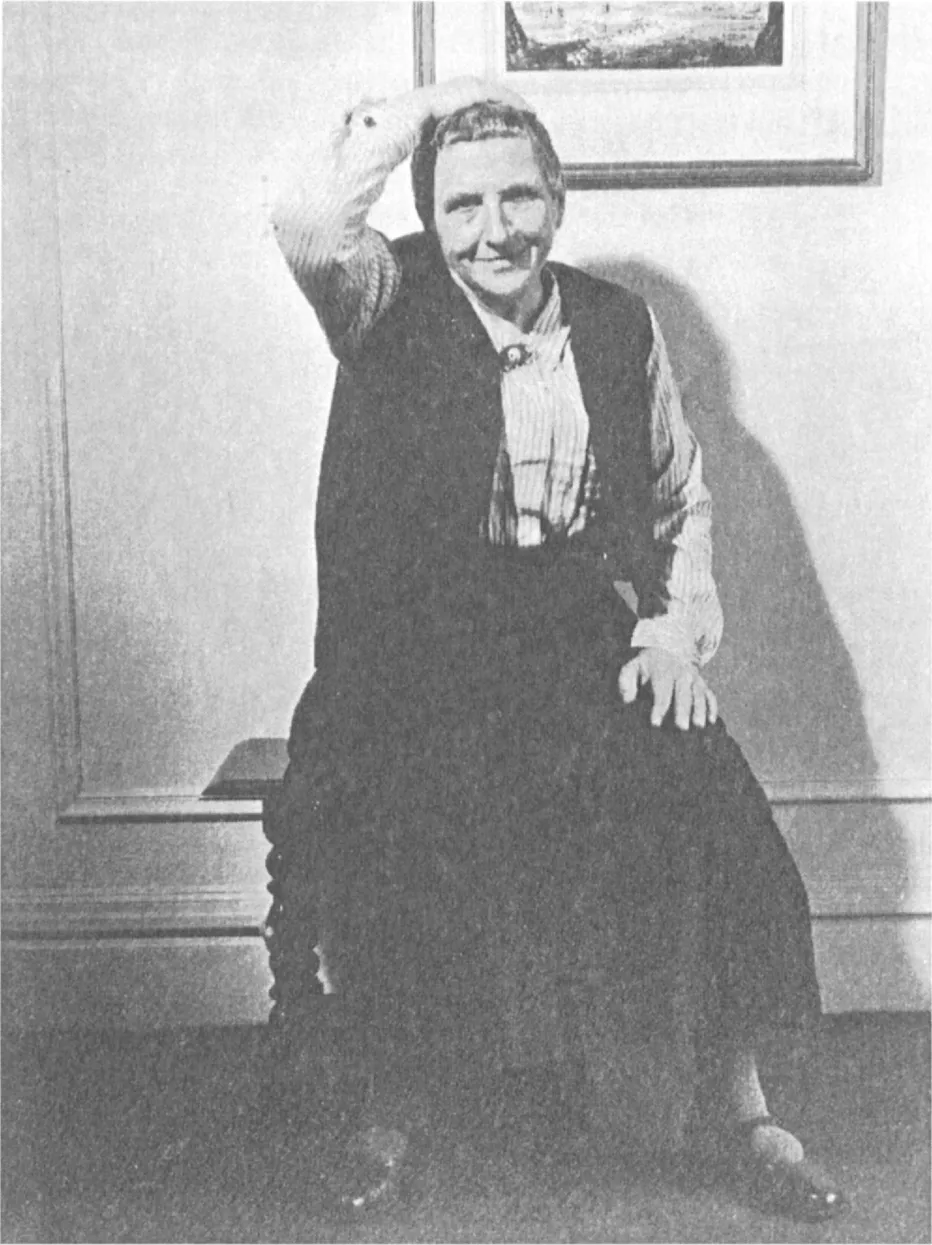

Figure 1 Gertrude Stein, 1934. Photograph by Rayhee Jackson. Used by permission of the Estate of Gertrude Stein.

In Stein's writing in general and in her drama in particular, the dominant artistic and cultural trends of the twentieth century emerge. Though she is perhaps the least well known of America's twentieth-century playwrights, she is the first genuine avant-garde dramatist of her country. As such, the history of experimental theater and drama in America is virtually inconceivable without her influence. One of America's earliest avant-garde theater groups, the Living Theater, began production in 1951 with Stein's "Ladies Voices" (1916). Robert Wilson produced herplay Doctor Faustus Lights the Lights (1938) in 1993 and, in 1998, the Wooster Group performed its adaptation of Stein's Doctor Faustus Lights the Lights, titled House/Lights. Richard Foreman has credited Stein as the most significant influence on his work and has referred to her as "the major literary figure of the twentieth century" (Bernstein 108). Anne Bogart's theater and Stan Brakhage's films have built their respective aesthetics upon Stein's principles, and parallels can be made between Stein and such contemporary experimental dramatists as Suzan-Lori Parks and Maria Irene Fornes.

Yet despite her dramatic influence, Stein's plays are rarely studied, even among Stein scholars. Similarly, the field of theater studies to date has largely ignored her dramatic output, just as the field of cinema studies has ignored her two screenplays. This is not to say that there is no criticism of Stein's drama at all. Marc Robinson devotes a chapter to Stein in his book The Other American Drama, and Stephen Watson's Prepare for Saints: Gertrude Stein, Virgil Thomson, and the Mainstreaming of American Modernism offers a thorough consideration of Stein's only theatrical success during her lifetime, Four Saints in Three Acts (written 1927, produced 1934). Recently, Arnold Aronson in his American Avant-Garde Theater: A History cites Stein as one of three major influences on American avant-garde theater. Most studies, however, treat Stein as a literary anomaly, critiquing her plays as if they were mistitled poetry or abstract prose. Of the few books that consider her plays at all, even fewer examine these works as scripts intended for performance.

Of the two books devoted exclusively to Stein's drama, only one—Betsy Alayne Ryan's Gertrude Stein's Theater of the Absolute (1984)—treats these plays as if they were written for performance. Unfortunately, however, Ryan attempts to cover all seventy-seven of Stein's plays with little separating of one play from another critically, and fails to connect Stein to the larger history of drama. Conversely, the other of these two books—Jane Palatini Bowers's "They Watch Me as They Watch This": Gertrude Stein's Metadrama (1991)— claims that Stein's plays are primarily "literary" writings. Bowers contends that Stein's use of the label "play" is more a function of her attitude toward language—her jouissance, as Bowers calls it—than an indication of Stein's serious desire to write for the stage. For Bowers, these plays are about theater, not for the theater. Of the two, Bowers's analysis of Stein has had a more lasting critical impact. Martin Puchner's Stage Fright: Modernism, Anti-Theatricality, and Drama, for example, takes up Bowers's reading of Stein in his analysis of Four Saints in Three Acts. In accordance with Bowers, Puchner argues that Stein's dramatic literature is best understood as closet drama, in part because of what he identifies as her "suspicion of the theater" (103). However, he also acknowledges that Four Saints is not written exclusively for the reader, but occupies a third category: "closet drama that is to be performed" (111).

It is my contention, however, that Gertrude Stein's drama deserves consideration on its own terms, as drama and as theater. These plays have an interior logic as well as a dramatic progression in which Stein continually works out her vision of modernity and modernism, culminating in her greatest dramatic work, Doctor Faustus Lights the Lights. The development of her dramatic vision can only be fully understood, moreover, in relation to three dominant cultural and artistic trends of the twentieth century: the development of the avant-garde, the evolution of cinema, and the emergence of homosexuality as an identity. At the intersection of these artistic and cultural movements, Stein's theater is both a precursor of American experimental performance and a landmark in American dramatic history.

Avant-garde drama, cinema, and queerness all begin around 1895. Within one year, Alfred Jarry wrote and later performed probably the first avant-garde play, Ubu Roi (1896); the Lumière brothers produced their first—and the first—film, Workers Leaving the Lumière Factory (1895); and Oscar Wilde's highly publicized trials of 1895 brought into public consciousness the concept of homosexuality as an identity. These three events resulted from a burgeoning modernity that directly contradicted the late nineteenth-century belief in rationalism and science, often exhibited dramatically in the form of the well-made play. If late nineteenth-century realism and naturalism emerged as a dramatic response to such scientific "certainties" as Auguste Comte's positivism, Karl Marx's theory of capitalistic exploitation, Sigmund Freud's psychoanalysis, and Charles Darwin's theory of evolution, then early twentieth-century avant-garde drama and film was founded on such theories of unpredictability and chaos as Werner Heisenberg's uncertainty principle, Albert Einstein's relativity, and Georg Simmel's fragmentation of perception in the urban environment.

One of the earliest examples of such drama is Ubu Roi (1896), in which Jarry adapts the story of Shakespeare's Macbeth as a grotesque comedy. In this landmark play, Jarry's two protagonists, Père and Mere Ubu, attempt to usurp King Wenceslas, ruler of an imaginary Poland. Père Ubu, one of the more notorious figures in avant-garde drama, was based on an earlier parody of Jarry's high school physics teacher, Professor Hébert. Ubu Roi opens with Père Ubu's famous line, "Merdre" ("Shit"), and includes Père Ubu's poisoning of dinner guests with excrement flung from a toilet brush, flushing nobles down an enormous toilet, and emerging quite unscathed from the whole ordeal after having been driven from Poland. As an avant-garde pioneer, Jarry attacked institutions of government, killing kings, deposing nobles, and flushing military leaders; he offended his middle-class audience with vulgar language and humor that combined the sexual with the scatological; and, most disturbingly for the time, Jarry omitted any explanation or moral condemnation for Ubu's behavior. Whereas other late nineteenth-century drama attempted to account for human behavior through either psychological or sociological explanations, Jarry made no excuses for his characters and their behavior. In fact, Jarry's earlier play, César-Antéchrist (1895), clearly marks the emergence of Père Ubu as a new godless incarnation of humanity. As Roger Shattuck writes of Ubu in The Banquet Years, "He is what he is because God has existed and has died ritually and actually, because Antichrist has had his reign on earth, and because the powers of true deity will triumph" (226). It is this view of humanity in relation to its God and its own psychology that would distinguish avant-garde drama from all previous forms of drama.

In addition to eliminating God and predictable human psychology from his drama, Jarry further intended that the brutal vision of humanity personified in Ubu should reflect the theater audience. He writes in his essay "Questions of the Theater" that he "intended that when the curtain went up the scene should confront the public like the exaggerating mirror in the stories of Madame Leprince de Beaumont, in which the depraved saw themselves with dragons' bodies, or bull's horns, or whatever corresponded to their particular vice" (174). Jarry recognized that realism and naturalism similarly attempted to reflect their audiences, but noted that "Ibsen's attack on [the audience] went almost unnoticed" (175). Jarry's attack, however, would not only be noticed by his audience, but would also change the path of modern drama.

On December 11, 1896, the first production of Ubu Roi opened at Le Theatre de l'Oeuvre in Paris. According to most accounts, the first word of the play incited a riot in which the audience eventually separated into two camps: enthusiasts and critics. In a stunning reversal for which the avant-garde would become renowned, the house lights were turned on in the middle of the outburst, allowing the performers on stage to watch the fighting below them. From the chaos of this one play, in both its writing and performance, the theatrical avant-garde was born. Bearing all the markers for the avant-garde to follow—nihilism, attacks on God and king, aggressive assaults on the audience, and the absence of moralizing and psychological explanations— Ubu Roi would inspire a generation of artists to follow. Most importantly, the play did what Jarry believed it could: it mirrored society and fundamentally altered that society's perception of itself.

Though not nearly as violent as the first production of Ubu Roi, the public presentation of the Lumière brothers' films were no less influential in the evolution of modern culture. Like Jarry's Ubu Roi, the Lumière brothers' films would fundamentally change the way people viewed the world. One of the most often told anecdotes of early cinema describes the first showing of the Lumiere film Arrival of the Train at the Station (1895). Apparently, the image of the train rushing toward the camera startled early audiences, sending them shrieking back from the screen. As Gerald Mast coyly states in his A Short History of the Movies, "Audiences would have to learn how to watch movies" (19). The accuracy of the story has been questioned as in David A. Cook's A History of Narrative Film, in which he writes, "It is difficult to imagine that the Lumières' educated, bourgeois audiences seriously expected a train to emerge from the screen and then run them down" (11). However, as Dai Vaughan suggests, "the particular combination of visual signals present in that film had had no previous existence other than as a real train pulling into a real station" (emphasis in original, 126), allowing for the possibility of just such a response.

While there are no such stories to accompany the Lumières' slightly earlier film, Workers Leaving the Lumière Factory, audiences were no less enchanted. The film gave audiences a previously unseen view of the world— themselves in motion. Arthur Knight describes the effect most exuberantly in The Liveliest Art when he calls the Lumières' motion-picture camera "the machine for seeing better" (14). He writes that, "to the public, [films] were a revelation. It was not merely the fact that movement and the shadow of the real world were captured by these machines—that had been done before—but now everything could be seen as large as life and, curiously, even more real" (14). The Lumières' film itself is uneventful. A static camera films groups of people leaving a factory. To a modern viewer accustomed to film and television, the movement is repetitive and, as the faces are mostly obscured in shadow, there is little to attract the eye other than the movement of the figures. Nevertheless, the film is a vital document of modernism and is intimately related to the theatrical avant-garde. The film achieves what few avant-garde performances would accomplish, despite repeated attempts. Workers Leaving the Lumière Factory transforms people, particularly the crowd, into objects. On film, especially in the work of the Lumières, people are repetitions of each other and their movement creates the unified flow of a mass, obscuring individuality.

Two important ideas are introduced through the Lumières' representation of their workers. First, the Lumieres capture humanity in what Siegfried Kracauer would later call "the mass ornament." In his 1927 essay of the same name, Karacauer first coined this tenm in his critique of the Tiller Girls, an all-female precision dance team from the 1920s and 1930s. He writes, "These [performers] are no longer individual girls, but indissoluble girl clusters whose movements are demonstrations of mathematics" (76). Although the workers leaving the factory are much looser in their organization than the precision-trained Tiller Girls, the workers also become human "clusters" rather than individuals. The image is one of mass—a group that becomes an aesthetic object. Secondly, the people represented in the film become mechanical and the group movement parallels the movement of a machine because of its uniformity. To quote again from Kracauer's "The Mass Ornament":

Although the masses give rise to the ornament, they are not involved in thinking it through. As linear as it may be, there is no line that extends from the small sections of the mass to the entire figure. The ornament resembles aerial photographs of landscapes and cities in that it does not emerge out of the interior of the given conditions, but rather appears above them. (emphasis in original, 77)

As with Père Ubu in Ubu Roi, film of mass spectacle eliminates individual psychology. In the films Kracauer identifies, humanity is presented as less grotesque than Ubu, but the filmic representation lacks the individualism to be found in realistic and naturalistic characterization. Furthermore, the film presents a mechanized way of viewing humanity. Because individuals are so similar in the Lumières' film, they begin to appear as copies of each other, as a few people duplicated or repeated. No matter how real the image seemed, the representation was unlike any that audiences had previously seen—full of people, yet devoid of individual personalities, and seemingly real, yet two-dimensional and mechanized—thus altering modern society's perception of itself. As awareness of this altered perception increased, film would eventually merge with the avant-garde, creating self-reflexive works that specifically addressed the role of vision and modes of seeing throughout the twentieth century.

This change in modern perception was simultaneously echoed in the trials of Oscar Wilde for "gross indecency." Ironically, Wilde initiated the very proceedings that would eventually send him to jail by filing a libel suit against the father of his lover, Lord Alfred Douglas. In a letter, the Marquess of Queensberry referred to Wilde as a "Somdomite" [sic], prompting Wilde's suit. The trial eventually turned on Wilde, however, and Queensberry was found to be justified in his derogatory reference to Wilde a sodomite. Shortly after losing the lawsuit, Wilde was arrested for "indecent acts" in April 1895. His trials were marked by public attention from the beginning. Newspapers from all over the world covered the scandal, including the New York Times. Before the first trial, a sale of photographs of Wilde caused such a riot that the police were called and the sale had to be stopped, English newspapers in particular relished the event, in one case calling Wilde the "High Priest of the Decadents."

It was during his first trial, which began on April 26, 1895, that Wilde first admitted to the "Love that dare not speak its name." In this now famous speech, Wilde defended this love as "the noblest form of affection" and "intellectual," equating such relationships with those described in Plato's philosophy and the sonnets of Michaelangelo and Shakespeare. His reply, however, was taken as an admission of indecency. Although his first trial failed to end with a unanimous verdict, his admission would eventually be his downfall. His second trial resulted in his conviction and he was subsequently sentenced to two years at hard labor. But more significant than the actual event of Wilde's trial was the effect of his conviction on the public. The emergence of a homosexual identity fundamentally changed society's perception of sexuality and its relation to being. As a recognizable homosexual, Wilde fundamentally destabilized assumptions not only about "normal" sexuality, but also about normal society. Similar to the effects caused by avant-garde drama and cinema, the emergence of the visible homosexual caused a fundamental shift in cultural perception. Moreover, this shift in perception was not simply the result of the assimilation of new information, as had occurred in the intellectual revolution created by such figures as Freud, Darwin, and Marx; rather, this new shift was the realization...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- General Editor's Note

- Acknowledgments

- Chapter 1 INTRODUCTION

- Chapter 2 "EYES ARE A SURPRISE": THE ORIGINS OF GERTRUDE STEIN'S DRAMA IN CINEMA

- Chapter 3 "LISTEN TO ME": STEIN AND AVANT-GARDE THEATER

- Chapter 4 ATOM AND EVE: DOCTOR FAUSTUS LIGHTS THE LIGHTS

- Chapter 5 "MY LONG LIFE": FINAL WORKS

- Chapter 6 "AMERICA IS MY COUNTRY": GERTRUDE STEIN AND THE AMERICAN AVANT-GARDE

- Appendix A A Chronological List of Gertrude Stein's Plays

- Appendix B A Chronological List of Professional Productions

- Appendix C A Chronological List of Dramatic Adaptations

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Mama Dada by Sarah Bay-Cheng in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Littérature & Critique littéraire. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.