- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Available until 4 Dec |Learn more

About this book

Using a wealth of international case studies and photos, Ecotourism: An Introduction provides an accessible and comprehensive introduction to the key foundations, concepts and issues related to Ecotourism, the fasted growing segment of the global tourism industry. Among the topics covered are: * the foundations of ecotourism

* tourism and ecotourism policy

* the economics, marketing and management of ecotourism

* the social and ecological impacts of tourism

* ecotourism and development

* the role of ethics in ecotourism

The book includes case studies from Scotland, Austria, the USA, Canada, Mexico and Australia.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Ecotourism by David A. Fennell,David Fennell in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Physical Sciences & Human Geography. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The nature of tourism

In this chapter the tourism system is discussed, including definitions of tourism and associated industry elements. Considerable attention is paid to attractions as fundamental elements of the tourist experience. Both mass tourism and alternative tourism paradigms are introduced as a means by which to overview the philosophical approaches to tourism development to the present day. Finally, much of the chapter is devoted to sustainable development and sustainable tourism, including sustainable tourism indicators, for the purpose of demonstrating the relevance of this form of development to the future of the tourism industry. This discussion will provide a backdrop from which to analyse ecotourism, which is detailed at length in Chapter 2.

Defining tourism

As one of the world’s largest industries, tourism is associated with many of the prime sectors of the world’s economy. Any such phenomenon that is intricately interwoven into the fabric of life economically, socioculturally, and environmentally and relies on primary, secondary, and tertiary levels of production and service, is difficult to define in simple terms. This difficulty is mirrored in a 1991 issue of The Economist:

There is no accepted definition of what constitutes the [tourism] industry; any definition runs the risk of either overestimating or underestimating economic activity. At its simplest, the industry is one that gets people from their home to somewhere else (and back), and which provides lodging and food for them while they are away. But that does not get you far. For example, if all the sales of restaurants were counted as travel and tourism, the figure would be artificially inflated by sales to locals. But to exclude all restaurant sales would be just as misleading.

It is this complex integration within our socio-economic system (a critical absence of focus), according to Clawson and Knetsch (1966) and Mitchell (1984), that complicates efforts to define tourism. Tourism studies are often placed poles apart in terms of philosophical approach, methodological orientation, or intent of the investigation. A variety of tourism definitions, each with disciplinary attributes, reflect research initiatives corresponding to various fields. For example, tourism shares strong fundamental characteristics and theoretical foundations with the recreation and leisure studies field. According to Jansen-Verbeke and Dietvorst (1987) the terms ‘leisure’, ‘recreation’ and ‘tourism’ represent a type of loose, harmonious unity which focuses on the experiential and activity-based features that typify these terms. On the other hand, economic and technical/statistical definitions generally ignore the human experiential elements of the concept in favour of an approach based on the movement of people over political borders and the amount of money generated from this movement.

It is this relationship with other disciplines, e.g. psychology, sociology, anthropology, geography, economics, which seems to have defined the complexion of tourism. However, despite its strong reliance on such disciplines, some, including Leiper (1981), have advocated a move away in favour of a distinct tourism discipline. To Leiper the way in which we need to approach the tourism discipline should be built around the structure of the industry, which he considers as an open system of five elements interacting with broader environments: (1) a dynamic human element, (2) a generating region, (3) a transit region, (4) a destination region, and (5) the tourist industry. This definition is similar to one established by Mathieson and Wall (1982), who see tourism as comprising three basic elements: (1) a dynamic element, which involves travel to a selected destination; (2) a static element, which involves a stay at the destination; and (3) a consequential element, resulting from the above two, which is concerned with the effects on the economic, social, and physical subsystems with which the tourist is directly or indirectly in contact. Others, including Mill and Morrison, define tourism as a system of interrelated parts. The system is ‘like a spider’s web— touch one part of it and reverberations will be felt throughout’ (Mill and Morrison 1985:xix). Included in their tourism system are four component parts, including Market (reaching the marketplace), Travel (the purchase of travel products), Destination (the shape of travel demand), and Marketing (the selling of travel).

In recognition of the difficulty in defining tourism, Smith (1990a) feels that it is more realistic to accept the existence of a number of different definitions, each designed to serve different purposes. This may in fact prove to be the most practical of approaches to follow. In this book, tourism is defined as the interrelated system that includes tourists and the associated services that are provided and utilised (facilities, attractions, transportation, and accommodation) to aid in their movement, while a tourist, as established by the World Tourism Organization, is defined as a person travelling for pleasure for a period of at least one night, but not more than one year for international tourists and six months for persons travelling in their own countries, with the main purpose of the visit being other than to engage in activities for remuneration in the place(s) visited.

Tourism attractions

The tourism industry includes a number of key elements that tourists rely upon to achieve their general and specific goals and needs within a destination. Broadly categorised, they include facilities, accommodation, transportation, and attractions. Although an in-depth discussion of each is beyond the scope of this book, there is merit in elaborating upon the importance of tourism attractions as a fundamental element of the tourist experience. These may be loosely categorised as cultural (e.g., historical sites, museums), natural (e.g., parks, flora and fauna), events (e.g., festivals, religious events), recreation (e.g., golf, hiking), and entertainment (e.g., theme parks, cinemas), according to Goeldner et al. (2000). Past tourism research has tended to rely more on the understanding of attractions, and how they affect tourists, than of other components of the industry. As Gunn has suggested, ‘they [attractions] represent the most important reasons for travel to destinations’ (1972:24).

MacCannell described tourism attractions as ‘empirical relationships between a tourist, a site and a marker’ (1989:41). The tourist represents the human component, the site includes the actual destination or physical entity, and the marker represents some form of information that the tourist uses to identify and give meaning to a particular attraction. Lew (1987), however, took a different view, arguing that under the conditions of tourist-site-marker, virtually anything could become an attraction, including services and facilities. Lew chose to emphasise the objective and subjective characteristics of attractions by suggesting that researchers ought to be concerned with three main areas of the attraction:

- Ideographic. Describes the concrete uniqueness of a site. Sites are individually identified by name and usually associated with small regions. This is the most frequent form of attraction studied in tourism research.

- Organisational. The focus is not on the attractions themselves, but rather on their spatial capacity and temporal nature. Scale continua are based on the size of the area which the attraction encompasses.

- Cognitive. A place that fosters the feeling of being a tourist, Attractions are places that elicit feelings related to what Relph (1976) termed ‘insider’ ‘outsider’, and the authenticity of MacCannell’s (1989) front and back regions.

Leiper (1990:381) further added to the debate by adapting MacCannell’s model into a systems definition. He wrote that:

A tourist attraction is a systematic arrangement of three elements: a person with touristic needs, a nucleus (any feature or characteristic of a place they might visit) and at least one marker (information about the nucleus).

The type of approach established by Leiper is also reflected in the efforts of Gunn (1972), who has written at length on the importance of attractions in tourism research. Gunn produced a model of tourist attractions that contained three separate zones, including (1) the nuclei, or core of the attraction; (2) the inviolate belt, which is the space needed to set the nuclei in a context; and (3) the zone of closure, which includes desirable tourism infrastructure such as toilets and information. Gunn argued that an attraction missing one of these zones will be incomplete and difficult to manage.

Some authors, including Pearce (1982), Gunn (1988) and Leiper (1990), have made reference to the fact that attractions occur on various hierarchies of scale, from very specific and small objects within a site to entire countries and continents. This scale variability further complicates the analysis of attractions as both sites and regions. Consequently, there exists a series of attraction cores and attraction peripheries, within different regions, between regions, and from the perspective of the types of tourists who visit them. Spatially, and with the influence of time, the number and type of attractions visited by tourists and tourist groups may create a niche; a role certain types of tourists occupy within a vacation destination. Through an analysis of space, time, and other behavioural factors, tourists can be fitted into a typology based on their utilisation and travel between selected attractions. One could make the assumption that tourist groups differ on the basis of the type of attractions they choose to visit, and according to how much time they spend at them (see Fennell 1996). The implications for the tourism industry are that often it must provide a broad range of experiences for tourists interested in different aspects of a region. A specific destination region, for example, may recognise the importance of providing a mix of touristic opportunities, from the very specific, to more general interest experiences for the tourists in search of cultural and natural experiences, in urban, rural and back-country settings. (‘Back’ regions are defined on p. 34.)

Attractions have also been referred to in past research as sedentary, physical entities of a cultural or natural form (Gunn 1988). In their natural form, such attractions form the basis for distinctive types of tourism which are based predominantly on aspects of the natural world, such as wildlife tourism (see Reynolds and Braithwaite 2001), and ecotourism (see Page and Dowling 2002). For example, to a birdwatcher individual species become attractions of the most specific and most sought-after kind. A case in point is the annual return of a single albatross at the Hermaness National Nature Reserve in Unst, Shetland, Scotland. The arrival of this species prompts birdwatching tourists immediately to change their plans in an effort to travel to Hermaness. The albatross has become a major attraction for birder-tourists, while Hermaness, in a broader context, acts as a medium (attraction cluster) by which to present the attraction (bird). Natural attractions can be transitory in space and time, and this time may be measured for particular species in seconds, hours, days, weeks, months, seasons, or years. For tourists who travel with the prime reason to experience these transitory attractions, their movement is a source of both challenge and frustration.

Mass and alternative tourism: competing paradigms

Tourism has been both lauded and denounced for its ability to develop and therefore transform regions into completely different settings. In the former case, tourism is seen to have provided the impetus for appropriate long-term development; in the latter the ecological and sociological disturbance to transformed regions can be overwhelming. While most of the documented cases of the negative impacts of tourism are in the developing world, the developed world is certainly not an exception. Young (1983), for example, documented the transformation of a small fishing farming community in Malta by graphically illustrating the extent to which tourism development—through an increasingly complex system of transportation, resort development, and social behaviour—overwhelms such areas over time.

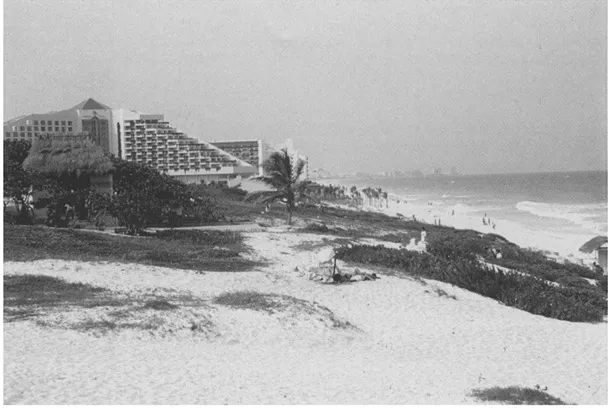

These days we are more prone to vilify or characterise conventional mass tourism as a beast, a monstrosity which has few redeeming qualities for the destination region, their people and their natural resource base. Consequently, mass tourism has been criticised for the fact that it dominates tourism within a region owing to its non-local orientation, and the fact that very little money spent within the destination actually stays and generates more income. It is quite often the hotel or mega-resort that is the symbol of mass tourism’s domination of a region, which are often created using non-local products, have little requirement for local food products, and are owned by metropolitan interests. Hotel marketing occurs on the basis of high volume, attracting as many people as possible, often over seasonal periods of time. The implications of this seasonality are such that local people are at times moved in and out of paid positions that are based solely on this volume of touristic traffic. Development exists as a means by which to concentrate people in very high densities, displacing local people from traditional subsistence-style livelihoods (as outlined by Young 1983) to ones that are subservience based. Finally, the attractions that lie in and around these massive developments are created and transformed to meet the expectations and demands of visitors. Emphasis is often on commercialisation of natural and cultural resources, and the result is a contrived and inauthentic representation of, for example, a cultural theme or event that has been eroded into a distant memory.

Admittedly the picture of mass tourism painted above is outlined to illustrate the point that the tourism industry has not always operated with the interests of local people and the resource base in mind. This was most emphatically articulated through much of the tourism research that emerged in the 1980s, which argued for a new, more socially and ecologically benign alternative to mass tourism development. According to Krippendorf (1982), the philosophy behind alternative tourism (AT)—forms of tourism that advocate an approach opposite to mass conventional tourism—was to ensure that tourism policies should no longer concentrate on economic and technical necessities alone, but rather emphasise the demand for an unspoiled environment and consideration of the needs of local people. This ‘softer’ approach places the natural and cultural resources at the forefront of planning and development, instead of as an afterthought. Also, as an inherent function, alternative forms of tourism provide the means for countries to eliminate outside influences, and to sanction projects themselves and to participate in their development—in essence, to win back the decision-making power in essential matters rather than conceding to outside people and institutions.

Plate 1.1 Tourist development at Cancún, Mexico

AT is a generic term that encompasses a whole range of tourism strategies (e.g. ‘appropriate’, ‘eco-’, ‘soft’, ‘responsible’, ‘people to people’, ‘controlled’, ‘small-scale’, ‘cottage’, and ‘green’ tourism), all of which purport to offer a more benign alternative to conventional mass tourism in certain types of destinations (Conference Report 1990, cited in Weaver 1991). Dernoi (1981) illustrates that the advantages of AT will be felt in five ways:

- There will be benefits for the individual or family: accommodation based in local homes will channel revenue directly to families. Also families will acquire managerial skills.

- The local community will benefit: AT will generate direct revenue for community members, in addition to upgrading housing standards while avoiding huge public infrastructure expenses.

- For the host country, AT will help avoid the leakage of tourism revenue outside the country. AT will also help prevent social tensions and may preserve local traditions.

- For those in the industrialised generating country, AT is ideal for cost-conscious travellers or for people who prefer close contacts...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Plates

- Figures

- Tables

- Case Studies

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- 1 The Nature of Tourism

- 2 Ecotourism and Ecotourists

- 3 Natural Resources, Conservation and Protected Areas

- 4 The Social and Ecological Impacts of Tourism

- 5 The Economics, Marketing, and Management of Ecotourism

- 6 From Policy to Professionalism

- 7 Ecotourism Programme Planning: A Focus on Experience

- 8 Ecotourism Development: International, Community, and Site Perspectives

- 9 The Role of Ethics in Ecotourism

- 10 Conclusion

- Appendix 1

- Bibliography