- 179 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Superior Memory

About this book

This book examines the nature and causal antecedents of superior memory performance. The main theme is that such performance may depend on either specific memory techniques or natural superiority in the efficiency of one or more memory processes.

Chapter 2 surveys current views about the structure of memory and discusses whether common processes can be identified which might underlie general variation in memory ability, or whether distinct memory subsystems exist, the efficiency of which varies independently of each other.

Chapter 3 provides a comprehensive survey of existing evidence on superior memory performance. It examines techniques which underlie many examples of unusual memory performance, and concludes that not all this evidence is explicable in terms of such techniques. Relations between memory ability and other cognitive processes are also discussed.

The remainder of the book describes the authors' own studies of a dozen memory experts, employing a wide variety of short- and long-term memory tasks. These studies provide a much larger body of data than previously available from studies of single individuals, usually restricted to a narrow range of tasks and rarely involving any systematic study of long-term retention.

The authors argue that in some cases unusual memory ability is not dependent on the use of special techniques. They develop some objective criteria for distinguishing between subjects who demonstrate "natural" superiority and those "strategists" who depend on techniques. Natural superiority was characterised by superior performance on a wider range of tasks and better long-term retention.

The existence of a general memory ability was further supported by a factor analysis of data from all subjects, omitting those who described highly-practised techniques. This analysis also demonstrated the independence of initial encoding and retention processes.

The monograph raises many interesting questions concerning the existence and nature of individual differences in memory ability (a previously neglected topic), their relation to other cognitive processes and implications for theories concerning the structure of memory.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

What is Superior Memory?

Feats of Memory

At the Second World Memory Championships held in London in the summer of 1993, many outstanding feats of memory were performed. Perhaps the most impressive was that of Dominic O’Brien, the eventual World Champion, who recalled 1002 randomly generated binary digits after half an hour’s study. The next best performer recalled only 600 digits! O’Brien also correctly recalled 100 randomly ordered digits spoken at the rate of one every two seconds on two out of three tests; the organisers of the competition had devised this as a task on which they assumed the maximum score was beyond the capacity of any of the competitors! In another task, Jonathan Hancock, who came second overall in the competition and who was the winner of the Championship of 1994, memorised 100 names to faces correctly after 15 minutes’ study.

This book is about unusual memory performances such as these and the people who produce them. What level of memory performance can human beings at their best achieve? How are such feats achieved? What do the findings tell us about memory in general? Researchers have often tended to turn to cases of memory impairment to answer questions about the structure and processes that underlie memory, but we believe that as much or more can be learned from studying exceptional memory performance and that exceptional performances raise many questions that tend to be neglected in the study of more normal memory abilities.

First, we will describe a few more examples of unusual memory, to illustrate the variety of ways in which superiority may be demonstrated, and we will consider what memory feats are popularly regarded as typical of someone with a good memory. Then we will draw out some of the problems and questions, which we will attempt to answer through a more systematic examination of the available evidence.

One of the oldest recorded feats of memory occurs in a story told by Cicero about the Greek poet Simonides, who was dining one day and reciting at a banquet. The roof later fell in and killed most of the assembled company, rendering their mangled bodies unrecognisable. Simonides escaped because he had been called away, and he was able to recall who had been sitting at each place in the banquet, so that the grieving relatives could each be given the correct body for the funeral rites. It seems from Cicero’s account that this was an example of incidental learning and, though the number of guests and hence the magnitude of the achievement is not recorded, Cicero says that it convinced Simonides of the efficacy of the method of loci (placing images of material to be remembered in a physical location) and he subsequently developed it as a deliberate memory method.

Epic poets are well-known for their ability to recite poems of enormous length telling the history of the nation’s heroes. This illustrates the importance of memory in cultures that depend on oral tradition for preserving information important to the community, such as flora, fauna, genealogies, and navigation routes. Studies of modern equivalents of these story tellers have shown that their recitations are not identical each time. Rather, the reciters “composed their songs anew on each occasion” (Lord, 1960). They had available themes covering recurring events, which might be made up of different combinations of formulae, smaller units describing specific incidents. The precise selection of formulae depended on the current mood and nuances of the situation being described. Examination of The Iliad or The Odyssey soon reveals that quite long standard descriptions of extended, recurring events are used many times throughout the poems, as well as smaller standardised fragments. Hence, rote learning is combined with other processes to produce the larger whole.

Rubin (1995) reinforces these conclusions in a recent detailed examination of oral traditions. He argues that what is handed down is a theme, not a verbatim memory; but multiple constraints determine stability without forcing the exact form of the text. These constraints also cue memory. They include organisation of meaning (obviously) and imagery, but sound patterns are equally important, especially rhythm, and also poetic devices such as rhyme and alliteration.

A rather different example of precise exceptional memory is that of the Shass Pollak, reported by Stratton (1982). These students of the Talmud could recall where each word appeared on the page of 12 volumes of text!

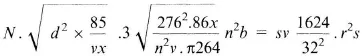

Turning to some examples of individual feats, which have been recorded in more detail, the famous Russian memory man Shereshevskii (S for short), whose memory was described in detail by the Russian psychologist Luria (1975), demonstrated many remarkable feats. One of the most impressive was his recall of the following complex arbitrary mathematical formula after only seven minutes’ study.

Fifteen years later he could recall in detail, without warning, the method he had used to code the formula. Luria (1975, p. 43) implies that he also recalled the formula itself but is not explicit on this point. The method used was to turn the arbitrary symbols into meaningful people and objects: “Neiman (N) came out and jabbed the ground with his cane (.).” The number 3 with the square root sign was a large tree with three jackdaws in it, x was a stranger in a black mantle, and so on.

Aitken (Hunter, 1977) was a mathematics professor who demonstrated unusual memory ability, as well as extraordinary mathematical talent. One of his most impressive feats was to reproduce from memory the names and regimental numbers of an entire platoon of 39 men without apparently having made any deliberate attempt to learn them or having any expectation that such recall would be needed.

A favourite activity of those wishing to demonstrate impressive feats of memory is to learn vast sequences of the digits of pi. In 1981, Rajan Srinivasan Mahadevan recited 31,811 such digits in 3 hours 49 minutes (including 65 minutes of breaks). In 1987, Hideaki Tomoyori outdid this by reciting 40,000 digits, but he took 17 hours 21 minutes, including 255 minutes of breaks, so he worked much more slowly. Compared with this, the feat of Philip Bond when tested by us seems modest. He memorised a 6 × 8 number matrix in five minutes and eight seconds (several of our subjects were faster), but was also able to recall it perfectly two months later. No other subject we have tested has matched this.

The tasks we have presented in our own studies of memory have been less demanding than the examples given above, but they have nevertheless sometimes produced individual performances unmatched by any of the other experts we tested, as in the example just given. Another example occurred with the task of recalling the correct names to 13 faces (each face-name pair being presented for only 10 seconds). Several subjects who use special methods have been able to recall all 13 names when tested immediately. The mean number recalled by those who have “normal” memories and use no special methods is only between 3 and 4 (see Chapter 4). The really demanding test, however, is to recall the names to the faces when they are shown without warning a week later. Few people recall more than a solitary name, and even the expert memorisers do little better than this. However, one of our subjects, JR, having recalled 12 names on the immediate recall test, could still recall all of them a week later. The performance of our control group of “normal” memorisers indicated that this feat would only occur by chance once in ten thousand million times! Moreover, JR claimed to have no special method for this astonishing achievement.

Anecdotes of extraordinary feats of memory demonstrated by experts in particular fields, such as music and chess, are legion. The conductor Zander, at a talk given at the Third World Memory Championships, recounted two such stories. As an 11-year-old the young Saint-Saens offered to play any one of Beethoven’s 32 piano sonatas from memory as an encore at a public performance. Toscanini once conducted the whole of the opera Aida from memory, having been called out of the orchestra at short notice; his eyesight was not adequate to reading the score.

These different feats are impressive for different reasons. Some demonstrate unusual ability to remember material where there is no indication of deliberate intention to learn (Simonides, Aitken); some impress by the sheer quantity of material which has been acquired by persistent effort (epic poetry, music, pi). It is quite likely that, in these cases, learning was faster than it would be in the majority of people attempting such a feat, if only because most people would surely find the task too slow and unrewarding to persist. However, usually no direct evidence is available on this point, so it remains unclear whether the feats should be attributed to superior memory ability as well as superior motivation and persistence. Hence, individuals with a wide knowledge of a particular type of material, especially when this is an unusual type, are impressive, but without adequate control of the conditions in which that knowledge was acquired, no conclusion can be drawn on their memory ability. Other cases, which demonstrate remarkable speed of acquisition or acquisition of an unusual amount of material in a controlled period (O’Brien’s binary digits, S’s formula, JR’s names), do demonstrate superior memory ability. The last two of these cases also meet a second major criterion for superior memory ability, namely unusually accurate long-term retention.

These then are the three criteria which will be used in this book when evaluating memory ability: (1) rapid acquisition of material or (2) acquisition of an unusually large quantity of material in a measured time, and (3) long-term retention of an unusually large quantity of material acquired under controlled conditions. The first two criteria exemplify superiority mainly in encoding processes and the third exemplifies superiority in retention. Superiority in retrieval ability may be a further distinct ability, but the available data are simply inadequate for evaluating this possibility.

As has been demonstrated, unusual memory ability has been shown in very many different ways and there is no certainty that excellence in one type of performance will guarantee excellence in all. One of the questions that will recur throughout this book concerns the generality of superior memory performance, over different types of memory task, different types of material, and different components of the overall memory process. Answering this question obviously requires more systematic data than are provided by isolated examples of unusual memory from different individuals.

Many of the examples given earlier involve deliberate learning of sequences of symbolic material (especially digits), rather than retention of the type of information that is the original raw material of everyday memory processes (objects, their use and value, routes, or individual characteristics such as facial features). There must be some doubt, therefore, about how far it is possible to draw conclusions about more “natural” memory abilities from studies of deliberate learning of very specific types of material. Since one of the central topics of this book will be individual differences in natural memory ability and their relation to wider aspects of cognitive performance, such issues will arise frequently in ensuing discussions.

It is perhaps significant that recognition memory for pictures is extraordinarily good even in non-expert subjects (Shepard, 1967; Standing, Conezio, & Haber, 1970), while memory for numbers is normally equally strikingly bad. What is more, memory for naturally encountered features of the environment is often based on incidental learning during a single exposure while carrying on other activities, whereas memory for material such as numbers most often depends on deliberate intent and strategy. The less natural the material, the greater the need for deliberate and special methods to achieve good memorisation. In such cases, unusually good performance tends to be rare and people are more impressed by it. So memory for long strings of numbers is more astonishing than ability to reproduce music or chess moves, and these abilities are in turn more impressive than memory for poetry or people’s faces or a series of events. There is, therefore, no guarantee that the person who has mastered the art of memorising long strings of digits has a good memory for where their car was parked in a strange town or where a particular face was previously seen.

Clever strategies can be very successful and can tell us a great deal about some aspects of memory function, but they are not, in general, necessary for everyday tasks and may not, without careful analysis, provide direct insights into the more automatic functioning of the memory system in everyday life.

Varieties of Memory-Natural and Acquired

When we appealed on the radio a few years ago for volunteers with good memories whom we could test, we received a wide variety of replies, claiming a variety of accomplishments. However, there were a number of common themes, which suggested that people usually regard themselves and others as having a good memory for one or more of the following reasons.

- They can remember and retell many events from their own life, especially from their early life.

- They can relate stories, poetry, jokes, etc. accurately and vividly.

- They remember individuals, particularly faces, names, and important biographical information.

- They can remember a large number of facts, either of general knowledge or from some specialist field (one of our respondents had memorised railway timetables).

- They remember routes of journeys.

- They have a so-called “photographic” memory, which stores an accurate image of visual inputs (more of this dubious claim later).

- They remember to do what they have planned to do.

These kinds of memory achievement are demonstrated in the situations for which memory evolved. Humans and other animals need to remember what happened in a particular situation so that they know what to do or what not to do next time it occurs; they need to remember characteristics of objects, including individuals of their own species; they need to remember the way back to the cave or a source of food; they need to persist in pursuit of a goal. Originally the individual with a better memory for these types of information would have had a better chance of survival. Once language developed, it became important to be able to encode and store experience in symbolic form and pass it on to others. Development of culture opened up other challenges to memory— retaining symbolic information communicated by others, tales and poems to pass on, dance routines, songs, and rituals, which required verbal, musical, and motor memory. However, these skills were a less direct product of evolution and were acquired by training rather than through genetic endowment. The development of writing rendered oral memory much less important, so such skills are now rarer in our society and thereby more impressive. More recently still, the advent of computer-based information systems, which permit storage and ready retrieval of huge amounts of information, is making oral memory still less important.

The main point that emerges from this discussion is that many of the most striking feats of memory performances such as those described earlier are not due to greater efficiency in an individual’s natural memory but to the application of learned methods of memorising to large quantities of symbolic material, especially unstructured symbolic material. Consequently, these demonstrations may tell us more about ways of improving some aspects of memory by deliberately learned methods than about natural automatic memory capacities and methods of improving the latter.

Objectives of this Monograph

The object of this monograph is to examine the evidence on superior memory performance in order to determine the factors that produce such performance and to consider the implications for theories of memory in general. In pursuit of this objective, the following are the main questions which will need to be examined.

- Is superior memory performance typically general or specific—does it occur over a wide range of tasks or only in specific types of task?

- If superiority is specific, is this due to a technique applicable to a particular type of task, or to a specialised memory system?

- What characterises successful techniques and can they be learned by anyone? Does the practice of techniques have effects on general memory efficiency?

- Does naturally outstanding memory ability occur? Is it general or is it specific to certain tasks, materials, or processes? On what does it depend? Is it qualitatively different from normal memory ability or just “more of the same”? How early in life is it apparent? Does it run in families? Is it characterised by good autobiographical memory, such as memory for early events in life?

- What are the relations between memory and other cognitive abilities?

The reasons for undertaking a study of superior memory performance are not simply curiosity about unusual abilities, but a belief that a better understanding of memory processes and possible memory theories can be developed from such studies. To date, general studies of individual differences in memory have not been highly revealing in relation to such questions, compared with the study of individual differences in intelligence, for example. Examining exceptional cases may enable a clearer picture to be developed of the extent to which variation in memory abilities is general or specific, the extent to which different proposed types of memory are independent of each other, the separability of different component processes, and other rela...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- 1. What is Superior Memory?

- 2. Previous Studies of Superior Memory

- 3. The Nature and Nurture of Memory

- 4. The Search for Superior Memories: Is Anyone Out There?

- 5. Memory Champions

- 6. General Memory Ability and Forgetting—Evidence from the Group Data

- 7. Conclusions

- References

- Appendix

- Author Index

- Subject Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Superior Memory by Elizabeth Valentine,John Wilding in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Cognitive Psychology & Cognition. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.