- 352 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Non-Existence of God

About this book

Is it possible to prove or disprove God's existence? Arguments for the existence of God have taken many different forms over the centuries: in The Non-Existence of God, Nicholas Everitt considers all of the arguments and examines the role that reason and knowledge play in the debate over God's existence. He draws on recent scientific disputes over neo-Darwinism, the implication of 'big bang' cosmology, and the temporal and spatial size of the universe; and discusses some of the most recent work on the subject, leading to a controversial conclusion.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Non-Existence of God by Nicholas Everitt in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Philosophy & Philosophy of Religion. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

PhilosophySubtopic

Philosophy of Religion1

Reasoning about God

I find every sect, as far as reason will help them, makes use of it gladly; and where it fails them, they cry out, ‘It is a matter of faith and above reason’.

(Locke 1964 vol. 2: 281)

The central role of the existence of God

Our principal concern will be with the question of whether God exists. The reason for making this the primary focus is not that the existence of God is the only interesting philosophical issue raised by religion. All religions which accept the existence of God consist of much more than a bare assertion of his existence. They consist as well of a set of doctrines about what kind of being he is and what significance his existence has for human life. Some religions, such as Judaism, Christianity and Islam, defend historical claims about the life histories of various individuals, such as Moses, Jesus or Mohammed; some put forward metaphysical claims (such as the doctrine of reincarnation or of life after death, or the possibility of intercessionary prayer, or Christianity’s doctrine of the Incarnation). Beyond the area of doctrine, most religions also involve an ethical and a ritual system. They aim to provide a set of rules or recipes by reference to which individuals can lead the good life, and sometimes by reference to which forms of social organisation can be judged. It is in this area that claims are sometimes made that religion can supply a meaning or purpose for human existence – or, more strongly, that only religion can do this. So most religions commit themselves to a good deal more than the bare assertion of God’s existence.

But there is nonetheless good reason for making the primary focus of a text such as this the existence of God. For a belief in God is not only essential to most religions (arguably to all, depending on the definition of ‘religion’ one favours); it is also what gives the point to the other parts of a religion. There would be no point in debating detailed issues about the ritual appropriate to a religion, unless one accepted the existence of the God on whom the religion was supposedly based. There would be no point in following a set of edicts because they had a supposedly divine origin, unless one accepted the existence of the God from whom they were supposed to originate.

Furthermore, it is to discussions of God’s existence that a number of able thinkers have devoted themselves, in a tradition running from early Christian thinkers such as Anselm; through Aquinas and other medieval scholastics; on through Descartes, Locke and Leibniz in the seventeenth century, Hume and Kant in the eighteenth, Mill in the nineteenth, Russell and Mackie in the twentieth, Swinburne, Plantinga and others in the twenty-first. The last few decades in particular have seen a philosophical resurgence of interest in the claims of theism. Contemporary thinkers about God have been able to draw on a wide variety of new ideas, from logic, from the philosophy of science, from probability theory, from epistemology, and from the philosophy of mind. What adds to the philosophical interest of this tradition of debate is that the participants in it have made wildly contradictory claims. At one extreme, Descartes claims that the existence of God can be known with greater assurance than I can know any claim about the physical world (such as for example that I have two hands), and also with greater assurance than any mathematical truth (such as for example that 2 + 2 = 4). At the other extreme is the conclusion which Hume reaches at the end of his Natural History of Religion: ‘The whole is a riddle, an aenigma, an inexplicable mystery. Doubt, uncertainty, suspence of judgement appear the only result of our most accurate scrutiny, concerning this subject’ (Hume 1976: 95).

The need to appeal to reason

Our central topic, then, is the existence of God. Since it is neither obviously true that he exists, nor obviously true that he does not, we need to examine what reasons there are to think that he exists, what reasons there are to think that he does not, to weigh them against each other, and thereby come to the most reasonable view we can.

So much seems obvious. But already, according to some thinkers, we have gone wrong. Some thinkers believe that this appeal to reasons for and against a belief in God is entirely inappropriate. We can distinguish between three different ways in which the appeal to reason has been thought inappropriate. One group of thinkers has claimed that it is somehow impious or even blasphemous or at least superfluous to reason about God’s existence. A second group, while not holding that it is impious, maintains that it is pointless because there are no reasons to be given. A third group allows that there are reasons to be given, but claims that all such reasons are inconclusive, and hence incapable of settling the issue anyway. Let us look in more detail at these three kinds of reservation about a search for reasons.

The claim that it is wrong to appeal to reason

According to thinkers in the first group, even if it is sensible to look for supporting evidence for some (perhaps most) of the beliefs we form, we stray from the path of righteousness in using this approach to the question of God’s existence. Human reason, they claim, is a feeble tool, whose use should be confined to mundane matters and not extended to holy mysteries. An early statement of the feebleness of human reason can be found in the famous (or should one say infamous?) remarks by Tertullian (c. 160 to c. 220 ad) in connection with the Incarnation that ‘just because it is absurd, it is to be believed . . . it is certain because it is impossible’ (quoted by B. Williams in Flew and MacIntyre 1963: 187).1 Later medieval writers who reiterated this mistrust of reason included St Peter Damian (1007–72), Manegold of Lautenbach (d. 1103), and Walter of St Victor (d. 1180). Commenting on Peter Damian, for example, Copleston notes that he believed that:

God in his omnipotence could undo the past. Thus though it happens to be true today that Julius Caesar crossed the Rubicon, God could in principle make the statement false tomorrow, by cancelling out the past. If this idea was at variance with the demands of reason, so much the worse for reason.

(Copleston 1972: 67)

This medieval hostility to reason persisted in some Catholic writings of the sixteenth century. St Ignatius Loyola, the founder of the Jesuits, wrote:

That we may be altogether of the same mind and in conformity with the Church herself, if she shall have defined anything to be black which to our eyes appears to be white, we ought in the like manner to pronounce it to be black.

(quoted in Hollis 1973: 12 fn.)

A rather more vigorous expression of the misleadingness of reason is found in Luther’s remark that ‘We know that reason is the Devil’s harlot, and can do nothing but slander and harm all that God says and does . . . Therefore keep to revelation and do not try to understand’ (quoted in ibid.).

Could it be a virtue to believe something not on the basis of supporting reasons, but on faith? That will depend on how we interpret the term ‘faith’. Some people draw a distinction between having faith in something, and having faith that something is the case, and claim that the relevant sense in a religious context is the former. But it seems quite clear that you cannot have faith in something unless you think that it exists. In this respect, having ‘faith in’ is like trusting, or revering or loving or admiring. I can sincerely urge you to put your trust in the Citizens Savings Bank – but not if I think that no such bank exists, nor if I have no idea whether there is any such bank. You can admire (say) the architect of the Parthenon – but not if you think that there was no architect. Again, you can revere (say) David Hume – but not if you think that there never was such a man. So even if having faith in God is a central religious ideal, it presupposes having a belief that God exists, having a faith that God exists.

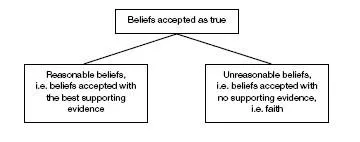

So what is it to believe something ‘on faith’? Some people use the term ‘faith’ in such a way that to believe something on faith is to believe it without any supporting reasons, or even (bizarrely) when the evidence one has goes against one’s belief – see, for example, Tertullian quoted above. What should we make of the claim that we may, or even should, form our beliefs ‘by faith’ in this sense of the word? Let us note first of all that in this sense of the word ‘faith’, the common phrase ‘to believe something on the basis of faith’ is a logical solecism. It suggests that there are two possible bases for a belief: either you can believe something on the basis of reasons, or you can believe it on the basis of faith. But ‘faith’ in this sense denotes the absence of a basis – and the absence of a basis is not an alternative kind of basis. To believe something ‘on the basis of faith’ would be more clearly expressed as believing something when you have no reason to think that your belief is true, when you have no justification for your belief, when you have no supporting evidence. It is not to have supporting evidence of a special (perhaps supernatural) kind. If there is any supernatural evidence, and it does indeed support a certain conclusion, then it is rational to use it in forming your beliefs and irrational to ignore it. So someone who believes that there is such evidence is wrong to denigrate the claims of reason – such a person wants to use reason themselves. The claim that a belief that God exists (or does not exist) needs supporting evidence does not imply that such evidence must be of any particular kind (such as ‘scientific’ or ‘naturalistic’). If (and it is a big ‘if’) there are kinds of evidence which are non-scientific and non-naturalistic, which are supernatural, and they are genuinely evidence (i.e. they really do make it more likely that the belief is true) then it would be irrational to ignore such non-standard evidence.

Further, it is unclear that even those like Luther who regard reason as ‘the Devil’s harlot’ can entirely dispense with it. Luther urges us to ‘keep to revelation’. But which revelation? Presumably people can be mistaken in thinking that God has revealed himself to them. Moses claimed that God had spoken to him – but so too did the Yorkshire Ripper, Peter Sutcliffe. Sutcliffe claimed to have received instructions from God, and there is no reason to doubt that his claim was sincere. On the basis of those instructions, he murdered nine young women (Cross 1995: 242). His grisly case raises sharply for us the question of how true revelations can be sorted out from false ones. Anyone who appeals to revelation as an alternative to reason, as Luther does, will surely nevertheless want to follow ‘the Devil’s harlot’ and claim that there are good reasons for thinking that Sutcliffe’s ‘revelation’ was a false one; and further (perhaps) that there are good reasons for thinking that Moses’ was a true one. The only alternative seems to be that there are no grounds at all for thinking that God did reveal himself to Moses and not to Peter Sutcliffe – and that looks like a very unattractive option.

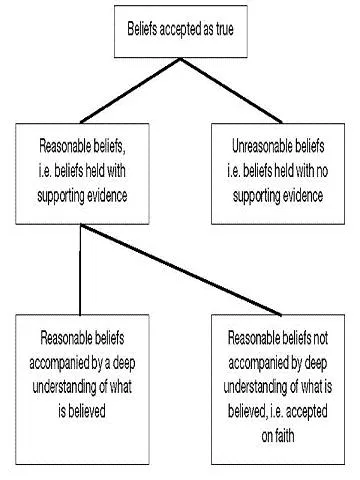

In fairness to theism, it should be noted that many theists, when they speak of faith, do not have in mind the irrational belief apparently endorsed by Luther. What they have in mind is a form of belief which is rational, in the sense that it is supported by the available evidence, but which isn’t accompanied by a deep understanding of what it is that is believed. An example will make this clear. If a mathematician tells me that Gödel’s Theorem (which says that it is impossible to formulate an axiomatisation of arithmetic which is both complete and consistent) is true, I may well believe her, because she is an expert and in a position to know, and she has no reason to deceive me. I have a belief, and it is a rational belief for me to hold, since I have good supporting evidence. But the grounds of my belief are so very different from and inferior to the grounds that the mathematician herself has, that it would be natural to give them different labels, to say that I believe Gödel’s Theorem as a matter of faith, whereas the expert sees exactly how and why the theorem must be true. In a similar way, a theist might well argue that a person who grows up in a religious community where all the recognised experts accept the existence of God, has good grounds for himself accepting the existence of God. But when he reaches intellectual maturity, he might well then seek to understand for himself what the evidence is for the existence of God, evidence that is to say which does not simply consist in the fact that many able people believe in his existence. Such a person would display, to use Anselm’s phrase, ‘faith seeking understanding’.

We could represent diagrammatically the difference between these two meanings for the term ‘faith’. The first conception is portrayed in Figure 1.1 and the second in Figure 1.2 (overleaf).

In the second sense of faith, it is of course rational to accept things as a matter of faith. But in this second sense, when someone tells us that she accepts something on faith, we can at once ask what reason she has for what she accepts. Accepting something on faith commits her to having a reason

Figure 1.1

Figure 1.2

for what she believes; and we can then raise the question whether the reason is indeed a good one. It is this sense of faith that Locke was evidently using when he said: ‘faith is nothing but a firm assent of the mind: which, if it be regulated, as is our duty, cannot be afforded to anything but upon good reason’ (Locke 1964 vol. 2: 281, second italics added).

A different sort of consideration has persuaded some modern philosophers (who are sometimes called Reformed Epistemologists) that there is no need to provide substantive reasons for God’s existence. Plantinga, for example, has argued that the demand for reasons is a product of a certain conception of (what he calls) warranted belief, and that that conception has been shown to be false. According to Reformed Epistemology, a believer can be fully warranted in believing a number of claims about God even if she cannot produce any argument in favour of such a belief, and even if she has no evidence or reason which can support the belief, or show it to be true or even probably true.

This sounds like a thorough-going rejection of the role of reason in the justification of beliefs about God, of the kind expressed by Luther. And certainly Plantinga himself wants to connect his views about religious belief with those of Reformation theologians like Calvin (hence the label Reformed Epistemology). We will look at Plantinga’s position more closely in the next chapter, but here we can note that in fact it is a good deal less hostile to reason than it sounds. In the first place, Plantinga distinguishes between reasons and warrant, and although he says that a warranted believer does not need reasons for her central beliefs about God, she does need warrant – although she does not need to know what her warrant consists in. Second, although the believer does not need reasons for her own belief to be justified, Plantinga never denies that there are reasons, both for and against beliefs about God. The warranted believer may be called upon to put forward and defend the pro-belief reasons, and to criticise the anti-belief reasons – in other words, to engage in reasoning about the existence and nature of God, in just the way that I am now urging both the believer and the sceptic to do.

It is an interesting philosophical question whether any of our beliefs have to be held without any supporting reasons. That is to ask whether we can give reasons for our reasons, and reasons for our reasons for our reasons, and so on indefinitely, or whether there are some things which we are justified in accepting without supporting reasons or grounds. But if there are any such things, a belief in God is prima facie not one of them. If reasons for and against a belief are available (and we shall shortly assert that they are available in the case of God’s existence), then we should use them to the best of our ability, not resolutely shut our eyes to them. A juror in a criminal case who pronounces on the guilt of the accused while making sure...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- The Non-Existence Of God

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Preface

- 1: Reasoning About God

- 2: Reformed Epistemology

- 3: Ontological Arguments

- 4: Cosmological Arguments

- 5: Teleological Arguments

- 6: Arguments to and from Miracles

- 7: God and Morality

- 8: Religious Experience

- 9: Naturalism, Evolution and Rationality

- 10: Prudential Arguments

- 11: Arguments from Scale

- 12: Problems About Evil

- 13: Omnipotence

- 14: Eternity and Omnipresence

- 15: Omniscience

- 16: Conclusion

- Notes

- Bibliography