- 304 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Stress, Coping, and Relationships in Adolescence

About this book

Unique and comprehensive, this volume integrates the most updated theory and research relating to adolescent coping and its determinants. This book is the result of the author's long interest in, and study of, stress, coping, and relationships in adolescence. It begins with an overview of research conducted during the past three decades and contrasts research trends in adolescent coping in the United States and Europe over time. Grounded on a developmental model for adolescent coping, the conceptual issues and major questions are outlined. Supporting research ties together the types of stressors, the ways of coping with normative and non-normative stressors, and the function that close relationships fulfill in this context.

More than 3,000 adolescents from different countries participated in seven studies that are built programmatically on one another and focus on properties that make events stressful, on coping processes and coping styles, on internal and social resources, and on stress-buffering and adaptation. A variety of assessment procedures for measuring stress and coping are presented, including semi-structured interviews, questionnaires, and content analysis. This multimethod-multivariate approach is characterized by assessing the same construct via different methods, replicating the measures in different studies including cross-cultural samples, using several informants, and combining standardized instruments with very open data gathering.

The results offer a rich picture of the nature of stressors requiring adolescent coping and highlight the importance of relationship stressors. Age and gender differences in stress appraisal and coping style are also presented. Mid-adolescence emerges as a turning point in the use of certain coping strategies and social resources. Strong gender differences in stress appraisal and coping style suggest that females are more at risk for developing psychopathology. The book demonstrates how adolescents make use of assistance provided by social support systems and points to the changing influence of parents and peers. It addresses controversial issues such as benefits and costs of close relationships or the beneficial or maladaptive effects of avoidant coping. Its clear style, innovative ideas, and instruments make it an excellent textbook for both introductory and advanced courses. Without question, it may serve as a guide for future research in this field.

This book will be of value to researchers, practitioners, and students in various fields such as child clinical and developmental psychology and psychopathology.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Stress, Coping, and Relationships in Adolescence by Inge Seiffge-Krenke in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Developmental Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Adolescent Coping: Pointing to a Research Deficit

In accordance with Petersen and Spiga (1982), adolescence is defined here as a period of transition characterized by accelerated processes of change in cognitive, social, and psychological functioning, accompanied by marked physical restructuring. As research on adolescent development shows (cf. Douvan & Adelson, 1966; Offer & Offer, 1975), successful adaptation in adolescence rather than crisis should be given more prominence in research. This is supported by the fact that continuous focusing on and solving of developmental problems seems to be the rule, whereas failure in the coping process is comparatively rare (e.g., Coleman, 1978). Recently, Bosma and Jackson (1990) suggested that adolescence can profitably be seen as a period of successful coping, and of productive adaptation. The adolescent is confronted with many different changes and is able to adapt to these changes in a constructive fashion, and in a way that results in developmental advance. Considering the large variety of tasks and problems encountered, adolescence is characterized by impressively effective coping in the majority of young people, a fact that has been widely neglected.

Lazarus (Lazarus & Launier, 1978) defined coping as “efforts … to manage (i.e., master, reduce, minimize) environmental and internal demands and conflicts which tax or exceed a person’s resources” (p. 288) and this shows that coping is a hypothetical construct that is sufficiently complex to take into account both person-specific and situation-specific aspects. In Lazarus’ research, stressors and social resources are also two important concepts. In the approach here, I go beyond the concepts of social resources and social support, and look more generally at relationships, which may contribute indirectly to coping. Because all three constructs (stress, coping, and relationships) cover a broad range of meanings (S. Cohen & Wills, 1985; Elliot & Eisdorfer, 1982; Lazarus & Folkman, 1991) and are not independent of each other, this chapter begins by analyzing more thoroughly research using adolescent coping as its key concept. The significance of coping behavior is evident in resiliency research showing that it is coping that makes the difference in both the adaptational outcome (Garmezy, 1983; Werner & Smith, 1982) and in research on symptomatology, illustrating that the most reliable predictor for mental health is not so much a lack of symptoms, but the competence with which age-specific developmental tasks are handled (Achenbach & Edel-brock, 1987; Compas, Davis, Forsythe, & Wagner, 1987).

In adult research, a tradition in coping has long been established (Lazarus & Folkman, 1991). In recent years, more interest has been shown in questions of coping behavior in adolescence, reflected by an increasing number of conferences and publications on this subject. Two different phases in research on adolescent coping are clearly apparent and are dealt with later on. Furthermore, approaches differ in Anglo–American and European studies. In the following, I sum up and comment on research on adolescent coping.

Historical Development and Theoretical Concepts in Coping Research

Before delineating research trends in adolescent coping, some introductory remarks on conceptualization and research trends in adult studies should be given. Since the publication of Lazarus’ (1966) book, Psychological Stress and the Coping Process, coping appears more and more often as an independent key word in the subject index of Psychological Abstracts (before, relevant publications on this topic could only be found under headings like “adaptation,” “mastery,” or “competence”). A review of the number of publications on coping since its introduction by Lazarus (1966) shows that, following a dramatic increase in research activity in the mid-1970s, interest in coping behavior has remained consistently high (see Seiffge-Krenke, 1986). In 1984, for example, the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology devoted an entire issue to coping in adults, and an equivalent volume summing up adolescent coping was published in the Journal of Adolescence in 1993, illustrating again a certain delay in research including adolescents.

As the term coping can include all types of observable reactions to a particular event, Pearlin and Schooler’s (1978) criticism regarding the “bewildering richness of coping relevant behavior” (p. 4) seems to be justified. The coping concept as used in this book, however, is based on the definition by Lazarus, which seems to have met the highest consensus. As stated already, Lazarus, Averill, and Opton (1974) defined coping as “problem solving efforts made by an individual when the demands he faces are highly relevant to his welfare . . . and where these demands tax his adaptive resources” (p. 15). This view of coping takes into account situational elements and classifies different reactions to potentially stressful or challenging stimuli. There are other approaches that emphasize the functionality and effectiveness of coping (cf. Pearlin & Schooler, 1978; Rodin, 1980). These authors postulate certain person-environment changes to be a result of the coping process and this is reflected in their definitions of coping. Lazarus focused primarily on the cognitive, information-processing aspects of coping, and shares with Haan (1977) and Meichenbaum, Henshaw, and Himel (1982) a view of coping as problem-solving behavior. However, even among those authors who regard coping as problem-solving behavior, there exist major differences. This is a result of different orientations and research traditions, and a result of independent approaches. This can be shown by comparing the work of Haan and Lazarus.

Both Lazarus et al. (1974) and Haan (1977) stressed the role of cognitive functions in coping with critical events. According to Lazarus’ theory, three interconnected cognitive discrimination and evaluation processes are necessary for successful problem solving: primary appraisal, secondary appraisal, and reappraisal. Whereas Lazarus emphasized cognitive evaluation processes in coping, Haan distinguished between successful coping, and processes of defense or fragmentation. As Haan explained, coping processes are goal-directed, flexible, and allow an appropriate expression of affect. Defense processes, on the other hand, are rigid and inappropriate to reality, including distortion of affect. These two processes differ only quantitatively with respect to the criteria of affect expression, reality orientation, and goal directedness; fragmentation, on the other hand, represents a switch into pathology: The reactions are automatic, ritualized, and irrational. Lazarus’ and Haan’s approaches to coping also differ with regard to the dynamics and stability attributed to the construct. Whereas Haan (1977) emphasized trait components, Lazarus stressed situational specifity. In his process-oriented model of coping, trait aspects are secondary and situations and actualization possibilities very much in the foreground. Sources of coping are to be found both in the person (problem-solving abilities, attitudes) and in the environment (financial resources, social support). Both determine the way coping is realized in a particular situation. In his classification of coping processes, Lazarus distinguished between the mode (e.g., action, inhibition of action, information seeking) and the function of coping (e.g., problem-oriented vs. palliative). Coping processes are the result of transactional relationships between situational and personality variables (Lazarus & Launier, 1978; Roskies & Lazarus, 1980): “Stress occurs neither in the person nor in the situation, although it is dependent upon both. It arises much more from the way in which the person evaluates the adaptive relationship” (Lazarus, 1981, p. 204). Lazarus chose the concept of transaction for this relationship because it emphasizes the reciprocal influence of personality and situational characteristics. Thus, it is not a one-sided, linear model, but a bidirectional model that takes into account the effects of the coping behavior itself on the person and the situation.

To sum up, the construct of coping has proved somewhat hard to pin down. A number of different definitions of coping exist, in part due to the fact that different aspects of the construct have been focused on, for example, the coping process, personal characteristics, person-environment interaction, or the effects of coping (Krohne, 1990). In addition to theoretical and conceptual problems, methodological problems arise (Panzarine, 1985). For example, how might the effect of situational components be distinguished from personal ones? Also, the determination of relevant situation parameters is crucial (Lazarus & Folkman, 1991). Further methodological problems may arise from the complicated temporal conditions of the individual parameters (Folkman & Lazarus, 1985). The confounding of coping with outcome is a problem outlined impressively by Lazarus and Folkman (1991), when efficacy is implied by coping and inefficacy by defense. The focus of research has undergone some change, too. Historically, the differentiation of various coping modalities (e.g., instrumental or palliative coping, cf. Lazarus & Launier, 1978) and the coping-defense debate (cf. Haan, 1974, 1977) was followed in the late 1970s by a shift in research trends, from a trait-oriented approach (Haan, 1974; Vaillant, 1977) to a transactional perspective (Lazarus et al., 1974). In this context it should be considered that coping research originally derived from animal experimentation and ego-psychoanalysis, and that both have influenced coping theory and measurement. Therefore, traditional models of coping tend to emphasize cognitive traits or styles, which results in speaking of people who are repressors or sensitizers or people who are deniers or copers. But trait conceptualizations and measures of coping underestimate the complexity and variability of actual coping efforts, and this has led to the development of models attempting to integrate aspects of both the person and the environment. Furthermore, the concept of stressors in this research has been refined. In the 1980s, a change from the analysis of critical events to the investigation of both mildly stressful, normative events (Kanner, Coyne, Schae-fer, & Lazarus, 1981) and long-term, chronic stressors has taken place (Lazarus & Folkman, 1991).

To conclude, many of the theoretical conceptualizations and operationaliza-tions arose from research on adults. Despite the impressive amount of research activity, coping research has not yet been able to provide satisfactory solutions to some conceptual and methodological problems.

Research Trends in Adolescent Coping: The First Phase (1967-1985)

Coping research on adolescents has not yet reached a comparable degree of differentiation. Due to the small amount of research activity, it has been limited to certain specific questions and approaches (cf. Seiffge-Krenke, 1986). Two phases can be clearly differentiated in research on adolescent coping: (a) a clinically oriented approach until the mid-1980s, and (b) a more developmentally oriented approach since about 1985. In these phases, different sampling and research methods have been used. In the following, the history and background of coping research on adolescents are described together with a summary of the more important results in this area. Possible reasons for the quantitative and qualitative differences between coping research in adults and adolescents are examined and an explanation is given for the differing approaches in Europe and the Anglophonic countries in early coping research. Since the later 1980s, both research trends are converging.

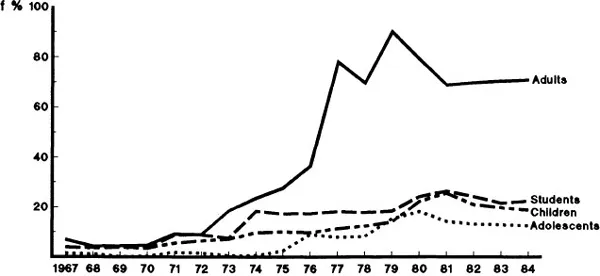

Upon analyzing the publications on coping that appeared between 1967 and 1984, it becomes apparent that over a period of nearly 20 years only about 7% of the publications are devoted to studies on adolescents, whereas 42% deal with adults and 17% with children. College students make up for a further 24% of the subjects, and in 10% of the studies age was not specified (see Fig. 1.1).

Fig. 1.1. Relative proportion of publications on the subject “coping” from 1967 to 1984, differentiated according to age groups (Source: Psychological Abstracts).

Regarding content, research on adults and adolescents has followed a similar path. A large number of studies in both age groups investigated coping with critical life events (31% of the studies on adults and 22% on adolescents) and coping with more everyday stressors (21% of the studies on adults and 11% on adolescents). In the literature, coping with illness apparently entails coping with a critical life event, but it appears to be a strong and homogeneous research question. Accordingly, we have categorized coping with serious illness separately. As one would expect, more research has been carried out on adults coping with a very serious, chronic illness than on adolescents (35% on adults vs. 24% on adolescents). Theoretical and methodological problems received very little attention in adolescent research; only 6% of the studies on adolescent coping are concerned with this question and consequently no new models have been presented in this early phase of coping research.

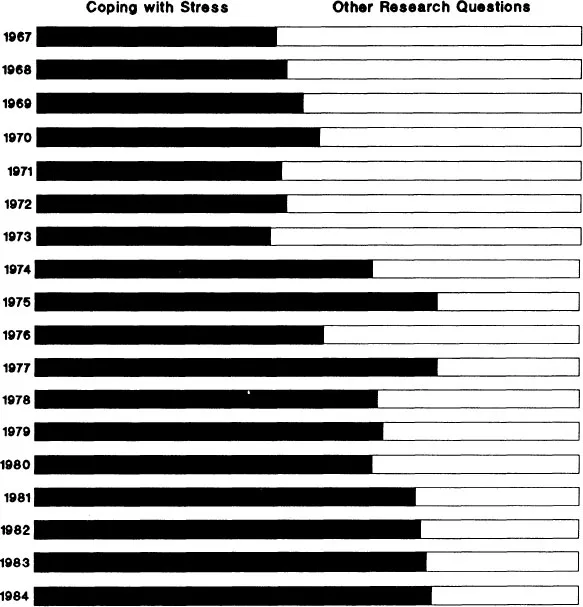

Adding up the percentages of the three topics “everyday stressors,” “physical illness,” and “critical life events,” it is shown in Fig. 1.2 that a general category “coping with stress” takes up more room in the literature than any other question of coping behavior, such as operationalization or methodology, developmental aspects, and so on.

Fig. 1.2. Classification of articles dealing with adolescents under the subject heading “coping,” subdivided into “coping with stress” and “other research questions” (Source: Psychological Abstracts).

As can be seen in Fig. 1.2, in 1984 two thirds of all publications on coping in adolescence were concerned with major and minor stress. The most important results of both research areas are discussed here.

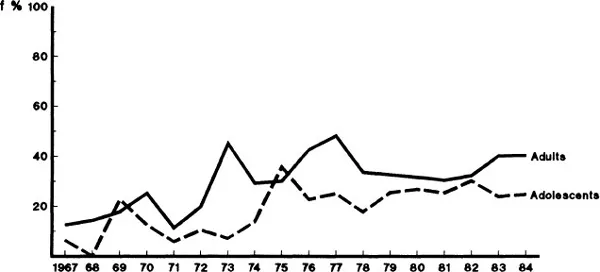

Coping with Critical Life Events

Since 1975, a great deal of attention has been directed toward critical life events in research on coping in adolescence. A comparison with studies on adults reveals similar developments and proportions of research activity—with a certain time lag in the research peaks (1973 for adults, 1975 for adolescents). However, one must take into account that of the 265 studies concerning coping with critical life events between 1967 and 1984 only 20% (49 studies) were carried out on adolescents (see Fig. 1.3).

Fig. 1.3. Comparison of research activities on critical life events in adolescents and adults between 1967 and 1984 (Source: Psychological Abstracts).

For a long time, the number of articles concerning clinical or epidemiological aspects of critical life events (cf. B. S. Dohrenwend & Dohrenwend, 1974, 1981) was disproportionately large. Critical life events had been used as an organizing principle to explain changes over the total life span, and increasing attention had been paid to social, financial, and psychological resources for coping with critical life events (Kahn & Antonucci, 1980; Nuckolls, 1972). An analysis of the literature on adolescent coping with critical life events shows that the problems in life event research on adults, particularly those from the earlier, epidemiologically oriented phase, are even stronger here. Studies on critical life events in adolescence, published between 1967 and 1984, were almost exclusively clinically oriented and can be roughly grouped into three categories: (a) studies on critical life events in the stricter sense compared to studies with adults; (b) studies on very serious, traumatic events; and (c) studies on the relationship between a critical life event and subsequent psychological disorder or physical illness.

In one third of the studies on adolescents, critical life events in the sense of Holmes and Rahe (1967) were analyzed. These studies investigated how adolescents coped with the divorce of their parents (M. Steinberg, 1974; Young, 1980), with the end of schooling (Weinberger & Reuter, 1980), or with unplanned pregnancy (e.g., Coletta, Hadler, & Gregg, 1981). Adolescents from broken homes and those faced with unexpected motherhood or fatherhood have been studied most intensively, considering also the effects of age, gender (Hendricks, 1980; Parks, 1977), and social support (Coletta et al., 1981). Unplanned pregnancy at an early age, for example, entails the following profound changes: Most adolescents leave school, give up their friends, and live in conditions of financial hardship. When a critical life event occurs at a time that differs substantially from the formal or informal age norms, it entails the risk of losing social support (Brim & Ryff 1980). One can therefore expect that because of the deviation from the age norm, pregnancy will affect a 14-year-old girl more strongly than a 24-year-old woman who has already fulfilled at least some of her developmental tasks.

Possibly because of the very threatening nature of critical life events, studies on adolescents were often combined with a crisis intervention program. In fact, the supplementary offer of crisis intervention seems to be specific to studies on adolescents. Weinberger and Reuter (1980), for example, accompanied a school class during their last year of school and helped preparing them to leave home, friends, and family and to anticipate a new life phase. Young (1980) set up a predivorce workshop for young people that included the integration and gradual coping with the divorce event over a period of several weeks, up to the final court date.

As in research on adults, the relation between critical life events and the occurrence of psychological illness has been investigated on adolescents. The question of interest is whether there is an association between critical life events and the occurrence of psychosomatic disorder (Zlatich, Kenny, Sila, & Huang, 1982), anxiety attacks (Dzegede, Pike, & Hackworth, 1981), attempted suicide (Isherwood, Adam, & Hornblow, 1982), or depression (Chatterjee, Mukherjee, & Nandi, 1981; Finlay-Jones & Brown, 1981). In these large epidemiological studies, several thousand subjects from different age groups were examined. The results for adolescents were similar to those of the younger and older subjects. For example, Andrews’ (1981) extensive longitudinal study of 1,500 subjects, including adolescents, found that individuals who were symptom-free at the beginning of the study did indeed undergo critical life events about 3 months prior to the occurrence of certain symptoms. As in studies on adults, however, the problem of causal interpretation remains.

About half of the publications between 1967 and 1984 on adolescent coping with critical life events are concerned with unusually stressful events such as kidnapping (Terr, 1979), rape (McCombie, 1976), temporary imprisonment (R. Johnson, 1978), homosexual abuse (R.Johnson, 1978), murder of family members or school friends (Meyers & Pitt, 1976; Morawetz, 1982; Petti & Wells, 1980), and traumatic accidents (Bulman & Wortman, 1977). Because of their low level of controllability and extremely harmful effects, all the events studied pose a particularly noxious threat to the development of these young people. Early occurrence of the events, lack of compensatory resources, and unavoidable finality are characteristic features. They seem to clash with other age-typical developmental tasks. Rape endangers the separation from home, the attainment of spatial independence, and the testing of sexuality just as it is beginning (McCombie, 1976). Cancer in a parent causes the adolescent to undergo overt role changes (e.g., increased responsibility for household tasks and siblings), but also leads to a subtle restructuring wherein the adolescent becomes the new partner of the remaining, healthy parent (Wellisch, 1979). Even the death of a sibling usually entails an increase in duties and responsibilities, sometimes resuiting in a stabilization of the parents at the expense of the adolescent’s own chance to mourn (Morawetz, 1982). A traumatic event, like the one described by Terr (1979, 1983) in Children of Chowchilla, where an entire school class was kidnapped, arouses regressive needs and fear of parental loss, thus hindering autonomy and separation.

Events that have been investigated under the topic critical life events are therefore primarily those that result in loss or damage as described by Lazarus (1966). In half of the studies, the event was so severe that the term trauma would be more appropriate. Analyses of how these events are dealt with focus on defense processes and symptom formation, rather than on successful coping. Global effects, often rated by people other than the affected (e.g., Hendricks, 1980; Morawetz, 1982; Parks, 1977), have been u...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- 1. Adolescent Coping: Pointing to a Research Deficit

- 2. Conceptual Approach for Studying Stress, Coping, and Relationships in Adolescence

- 3. An Analysis of the Coping Process

- 4. Assessment of Daily Stressors: Event Parameters and Coping

- 5. Ways of Coping with Everyday Problems and Minor Events

- 6. Internal Resources and Their Effect on Coping Behavior

- 7. Changes in Stress Perception and Coping Style as a Function of Perceived Family Climate

- 8. The Unique Contribution of Close Friends to Coping Behavior

- 9. Stress, Coping, and Relationships as Risk and Protective Factors in Explaining Adolescent Depression

- 10. Conclusions

- Appendix

- References

- Author Index

- Subject Index