- 246 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

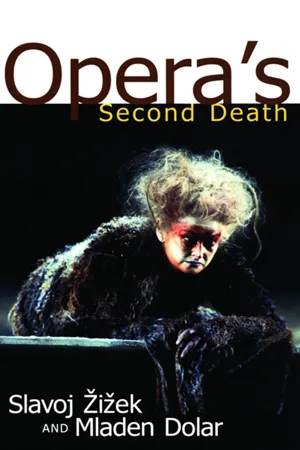

Opera's Second Death

About this book

Opera's Second Death is a passionate exploration of opera - the genre, its masterpieces, and the nature of death. Using a dazzling array of tools, Slavoj Zizek and coauthor Mladen Dolar explore the strange compulsions that overpower characters in Mozart and Wagner, as well as our own desires to die and to go to the opera.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Topic

ArtSubtopic

Popular Culture in Art“I DO NOT ORDER MY DREAMS”

SLAVOJ ŽIŽEK

In the accompanying text to one of the recordings of Mozart's Così, the partnership of Mozart and da Ponte is proclaimed “as memorable as those of Verdi and Boito, Gilbert and Sullivan, Strauss and Hofmannstal, or Wagner with himself,”1 The surprising thing is how one is allowed to enumerate Wagner's incestuous self-relationship in a series with other, “normal,” relationships, implying that Wagner was lucky to encounter the right librettist, that is, himself—a formulation that fits perfectly Wagner's unabashedly self-centered reading of the previous history of the opera and music in general: The features he emphasizes as most progressive in previous composers (say, the great finale of the Act II of Mozart's Le nozze) are the features he is able to read as pointing forward toward himself, toward his own notion and practice of the “music drama.” However, what if Wagner was right? What if his work effectively marks a unique achievement, a turning point that enables us to interpret properly and retroactively the ambiguities and breaks of the previous composers as well as to conceive of what follows as the disintegration of the unique Wagnerian equilibrium? Borges once remarked, apropos of Kafka, that some writers have the power to create their own precursors—this is the logic of retroactive restructuring of the past through the intervention of a new point-de-capiton: A truly creative act not only restructures the field of future possibilities but also restructures the past, resignifying the previous contingent traces as pointing toward the present. The underlying wager of the present essay is to endorse the notion that such is the position of Wagner. To put it in a naive and direct way, what if Tristan and Parsifal simply and effectively are (from a certain standpoint, at least) the two single greatest works of art in the history of humankind?2

The proper counterpart to Dolar's essay on Mozart would have been to start with The Flying Dutchman, which occupies in Wagner's opus the same structural role as The Abduction from the Seraglio in Mozart: It directly renders its elementary matrix. That is to say, although Mozart's operas present a series of variations on the same basic motif (the master's gesture of mercy that reunites the amorous couple), The Abduction from the Seraglio, with its uniquely naive assertion of the all-conquering force of love, clearly stands out as—in no way the best, and precisely for that reason—directly embodying this basic motif (the finale of its Act II, with its triumphant “Es lebe die Liebe!” quartet, is unique in its naïveté, in its lack of later, famous Mozartean irony). When, after the low point of Così fan tutte, with its uncanny Pascalean conclusion that love is mechanically generated by following the external ritual, Mozart endeavors to reestablish the pure naïveté of the power of love in The Magic Flute; this return to origins is already faked, tainted with artificiality, like the parents who, in telling stories to the children, pretend to really believe them.

And it is similar with Wagner: With regard to the purity of The Flying Dutchman, one is even tempted to claim that Tannhäuser and Lohengrin, although (in Wagner's lifetime) his most popular operas, are not truly representative of his style (see Tanner 1997) because they lack a proper Wagnerian hero. Tannhäuser is too common, simply split between pure spiritual love (for Elizabeth) and the excess of earthly erotic enjoyment (provided by Venus), unable to renounce earthly pleasures while longing to get rid of them; Lohengrin is, on the contrary, too celestial, a divine creature (artist) longing to live like a common mortal with a faithful woman who would trust him absolutely. Neither of the two is in the position of a proper Wagnerian hero, condemned to the undead existence of eternal suffering (the closest we come to it is, the hero's long “Rome narrative” toward the end of Tannhäuser, the first full example of the Wagnerian hero's protracted suffering that prevents him to die). And is it not that, again, in a similar way, Meistersinger is too common with its acceptance of social reality and that Parsifal is too celestial in its rejection of sexual love so that the triad of Tristan, Meister singer, and Parsifal repeats at a higher power the triad of The Flying Dutchman, Tannhäuser, and Lohengrin!3 However, because I already made an attempt at such a reading,4 I would prefer to accomplish here a similar move in the opposite direction: to read Wagner's Tristan as the zero-level work, as the perfect, ultimate formulation of a certain philosophico-musical vision, and then to read the later works (of Wagner himself as well as of other composers) as the variations on this theme, as posts on the path of the disintegration of Tristan's unique synthesis that culminates in the much-celebrated Liebestod toward which the entire opera tends as its final resolution.

The Death Drive and the Wagnerian Sublime

We sing for different reasons: At the very beginning of his Eugene Onegin, Pushkin presents the scene of women singing while picking strawberries on a field—with the acerbic explanation that they are ordered to sing by their mistress so that they cannot eat strawberries while picking them. So why does Isolde sing? The first thing to note is the performative, self-reflective dimension of Isolde's final song. When Romeo finds Juliet dead in the finale of Prokofiev's ballet Romeo and Juliet, his dance renders his desperate effort to resuscitate her. However, here the action takes place at two levels, not only at the level of what the dance renders but also at the level of the dance itself. The fact that the dancing Romeo is dragging around Juliet's corpse, which is suspended like a dead squid out of water, can be read as his desperate effort to return this inert body to the state of dance itself, to restore its capacity to magically sublate gravity and freely float in the air. Thus, his dance is in a way a reflexive dance aimed at his dead partner's very (dis)ability to dance. The designated content (Romeo's lament of the dead Juliet) is sustained by the self-reference to the form itself. And it is homologous with Isolde's singing: In the sublime moment of Liebestod, Isolde's singing as such is at stake. Here singing does not simply represent her inner state, her longing to unite herself with Tristan in her death—she dies of singing, of immersing into the song; in other words, the culminating identification with the voice is the very medium of her death.

In what, then, does this Liebestod consist? The answer seems to be clear: Wagner's eclectic combination of Buddhist nirvana (mediated through Schopenhauer) and metaphysical eroticism. The structuring opposition is the one between day and night: the daily universe of symbolic obligations and honors versus its nightly abrogation in the “höchste Lust” of erotic self-obliteration. No wonder that this sinking into the oblivious night is associated with Ireland—as Heinrich Boll reports in his marvelous Irish Diary (1957), Irish pubs featured small booths, isolated with a leather curtain, with straps by means of which a drunkard could attach himself to the seat and immerse himself in the “night of the world,” getting away from the daily world of family, honor, profession, and obligations and swimming in the darkness till he runs out of money and is thus reluctantly compelled to return home. So everything seems clear: the eroticized death drive, the suspension of the symbolic order—but here, however, the first complication arises. Yes, Tristan is the story of a lethal passion that finds its resolution in ecstatic self-obliteration, but the very mode of this self-obliteration is as far as possible from the passionate violation of all rules—the immersion into night is rendered as a cold, declamatory, distanced procedure. No wonder that perhaps the ultimate staging of Tristan in the last decades, the one by Heiner Mueller, Brecht's unofficial heir, emphasized precisely this aspect of an almost mechanically enacted ritual.

A look at the other Wagnerian heroes can be of some help here. Starting with their paradigmatic case, the Flying Dutchman, they are possessed by the unconditional passion for finding ultimate peace and redemption in death. Their predicament is that at some time in the past they committed some unspeakably evil deed, and the price they must pay is not death but condemnation to a life of eternal suffering, of helplessly wandering around, unable to fulfill their symbolic function. This gives us a clue to the exemplary Wagnerian song, which is the complaint (Klage) of the hero displaying his horror at having to exist as an undead monster, longing for peace in death; consider the Dutchman's great introductory monologue and the lament of the dying Tristan and the two great complaints of the suffering Amfortas. Although there is no great complaint by Wotan, Brünnhilde's final farewell to him—“Ruhe, ruhe, du Gott!”—points in the same direction: When the gold is returned to the Rhine, Wotan is finally allowed to die peacefully.

Wagner's solution to Freud's oppositional placement of Eros and Thanatos is thus the identity of the two poles: Love itself culminates in death, its true object is death, and longing for the beloved is longing for death. Is what Freud called the death drive (Todestrieb) the urge that haunts the Wagnerian hero? It is precisely the reference to Wagner that enables us to see how the Freudian death drive has nothing whatsoever to do with the craving for self-annihilation, for the return to the inorganic absence of any life-tension. The death drive does not reside in Wagner's heroes’ longing to find peace in death; it is, on the contrary, the very opposite of dying—a name for the undead state of eternal life itself, for the horrible fate of being caught in the endless, repetitive cycle of wandering around in guilt and pain. The final passing away of the Wagnerian hero (the death of the Dutchman, Wotan, Tristan, Amfortas) is therefore the moment of their liberation from the clutches of the death drive. Tristan, in Act III, is not desperate because of his fear of dying but because without Isolde he cannot die and is condemned to eternal longing—he anxiously awaits her arrival so as to be able to die. The prospect he dreads is not that of dying without Isolde (the standard complaint of a lover), but rather that of the endless life without her. The paradox of the Freudian death drive is therefore that it is Freud's name for the very opposite of what the term would seem to signify, for the way immortality appears within psychoanalysis, for an uncanny excess of life, for an undead urge that persists beyond the (biological) cycle of life and death, of generation and corruption.5 The ultimate lesson of psychoanalysis is that human life is never “just life”: Humans are not simply alive but are possessed by the strange desire to enjoy life in excess, passionately attached to a surplus that derails the ordinary run of things.

Such a striving to experience life at its excessive fullest is what Wagner's operas are about. This excess inscribes itself into the human body in the guise of a wound that renders the subject undead, depriving him or her of the capacity to die (apart from Tristan's and Amfortas's wound, there is, of course, the wound, the one from Kafka's “A Country Doctor”); when this wound is healed, the hero can die in peace. On the other hand, as Lear (2000) is right to emphasize, the figure of the balanced ideal life delivered of the disturbing excesses (say, the Aristotelian contemplation) is also an implicit stand-in for death. Wagner's insight was to combine these two opposite aspects of the same paradox: Getting rid of the wound, healing it, is ultimately the same as fully and directly identifying with it. Does this insight not concern the very core of Christianity? Is Christ not the one who healed the wound of humanity by fully taking it upon himself? It is here that the originality of Wagner appears: He gave to the figure of Christ an uncanny twist. Although Christ was the pure one who took upon himself the wound (the highest suffering), Parsifal (the Wagnerian Christ) does not heal the wound of Amfortas by taking it upon himself; in clear contrast to Christ, he brings redemption by fully retaining his purity, by resisting the temptation of the excess of life (the temptation that brought devastation to the Kingdom of the Grail, when Amfor-tas's father, Titurel, succumbed to it by excessively enjoying the Grail) and not by assuming the burden of sin. For this reason, Parsifal does not have to die but can directly impose himself as a new ruler—Gutman is right to claim that Parsifal's “temple scenes are, in a sense, Black Masses, perverting the symbols of the Eucharist and dedicating them to a sinister god (1990: 432).

In the history of opera, this excess of life is discernible in two main versions, Italian and German, Rossini and Wagner—so, maybe, although they are the great opposites, Wagner's well-known private sympathy for Rossini, as well as their meeting in Paris, does bear witness to a deeper affinity. In contrast to Wagner's universe, Rossini's is decidedly pre-Romantic—a universe in which the evil characters feel the need to declare their evil to their victims—even Pizarro, in the great confrontation in Act II of Beethoven's Fidelio, declares who he is to Florestan before proceeding to kill him; he wants Florestan to know who will kill him. The darker undertone of such self-display can be discerned in de Laclos's Les liaisons dangereuses, in which Valmont, the hero, wants to seduce Madame de Tourvel not in a reckless moment of passion but with her full consciousness—he wants her to see herself being humiliated and unable to resist it: “Let her believe in virtue, but let her sacrifice it for my sake; let her be afraid of her sins, but let them not check her.”6 Valmont's plan is thus “to make her perfectly aware of the value and extent of each one of her sacrifices she makes; not to proceed so fast with her that the remorse is unable to catch up; it is to show her virtue breathing its last in long-protracted agonies; to keep that somber spectacle ceaselessly before her eyes” (Laclos 1961: 150). Not until the morning after will awareness of her act catch up with her. The situation here is antitragic: In a tragedy proper, the subject accomplishes the fateful act unaware of its consequences, which catch up with him only afterward; here, however, no temporal gap opens up space for the tragic experience because the act itself coincides with the full awareness of its consequences. This is the sadist's position of transposing onto the Other the subjective split at its purest.

In a homologous way, the two men in Mozart's Così fan tutte want to have their fiancées see themselves humiliated. The point is not just to test their fidelity but to embarrass them by way of compelling them to confront publicly their infidelity (recall the finale, when, after the marriage contract with the two Albanians, the two men return in their proper dresses and then let the fiancées know that they themselves had been the Albanians). The enigmatic desire is not the women's (is it stable or fleeting?), but the men's: What kind of imp of the perverse propels the two young gentlemen to submit the women to such a cruel ordeal? What is pushing them to throw into disarray the harmonious idyll of their love relationship? Obviously, they want their fiancées back, but only after having been confronted with the vanity of their feminine desire. As such, their position is strictly that of the Sadean pervert: their aim is to displace to the Other (victim) the division of the desiring subject; that is, the unfortunate fiancées must assume the pain of finding their desire repulsive.

With the typical late Romantic villain (say, Scarpia in Puccini's Tosca), we get a thoroughly different constellation, discernible not only in the supremely obscene finale of Act I but also throughout all of Act II: Scarpia not only wants to possess Tosca sexually but wants to witness her pain and her impotent fury provoked by his acts: “How do you hate me!... This is how I desire you!” Scarpia wants to generate in his object a hatred that arises from fury at having been reduced to powerlessness. He does not want her love but rather her giving herself to him as the act of utter humiliation, on behalf of her love for Mario, not for him. His is the hatred of the feminine object: Scarpia's true partner is the man desired/loved by the woman, which is why his supreme triumph is when Mario sees Tosca surrender herself to Scarpia out of love for him and curses/rejects her violently for that. Therein resides the difference between Scarpia and Valmont: Although Valmont wants the woman to hate herself while surrendering herself, Scarpia wants her to hate him, the seducer. (See Braunstein 1986: 91–92.)

Rossini belongs to this same series of self-display—however, with a twist. His great male portraits, the three from Barbiere (Figaro's “Largo il factotum,” Basilio's “Calumnia,” and Bartolo's “Un dottor della mia sorte”), plus the father's wishful self-portrait of corruption in Cenerentola, enact a mocked self-complaint, wherein one imagines oneself in a ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Introduction: For the Love of Opera

- Mladen Dolar / If Music be the Food of Love

- Slavoj Žižek/ “I do not Order My Dreams”

- Chapter 1 / “Deeper than the Day Could Read”

- Chapter 2 / “The Everlasting Irony of the Community”

- Interlude / The Feminine Excess

- Chapter 3 / Run, Isolde, Run

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Opera's Second Death by Slavoj Zizek,Mladen Dolar in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & Popular Culture in Art. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.