- 544 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Manual of Fertilizer Processing

About this book

This Manual of Fertilizer Processing, which is the fifth volume of the Fertilizer Science and Technology series. Francis (Frank) T. Nielsson, the editor of the book, has over 40 years of experience in the fertilizer industry, ranging from ammonia manufacture to the extraction of uranium from phosphoric acid, but he is best known for his work with compound or "mixed" fertilizers—fertilizers that contain two or more of the primary plant nutrients: nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium. Compound fertilizers also may contain one or more of the ten other elements that are essential to plant growth.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Manual of Fertilizer Processing by Nielsson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Biology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Outlook, Concepts, Definitions, and Scientific Organizations for the Fertilizer Industry

OUTLOOK FOR THE FERTILIZER INDUSTRY

Introduction

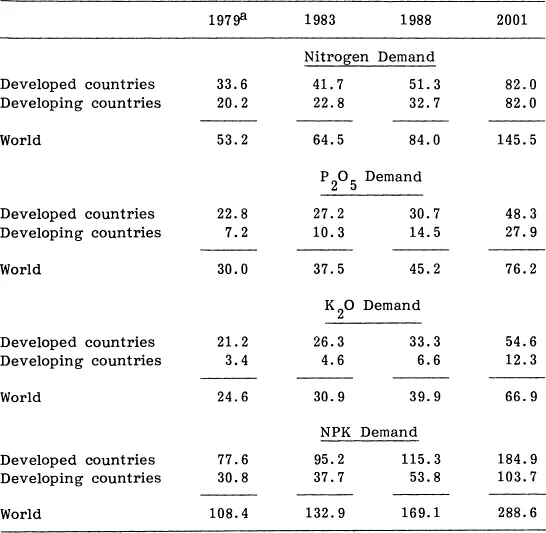

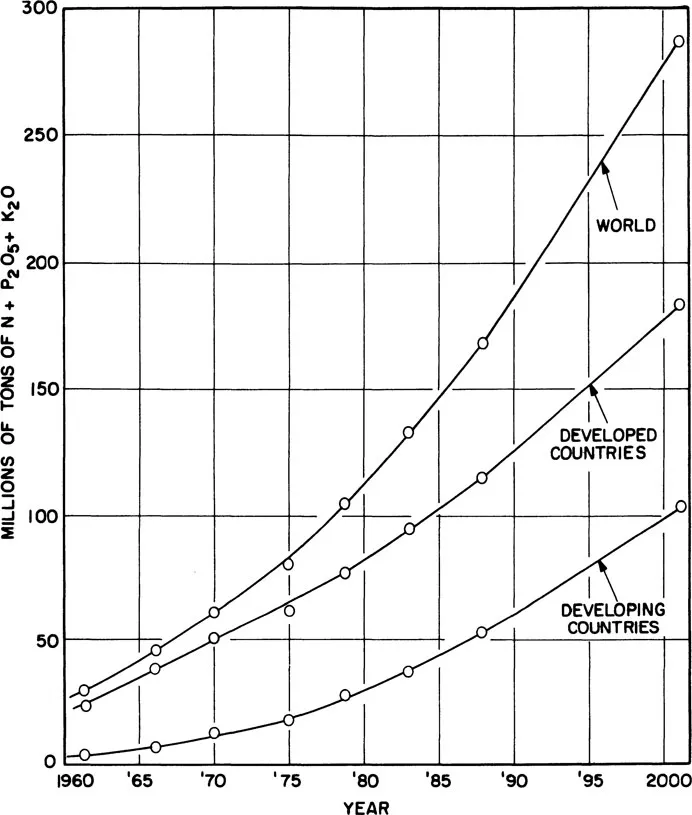

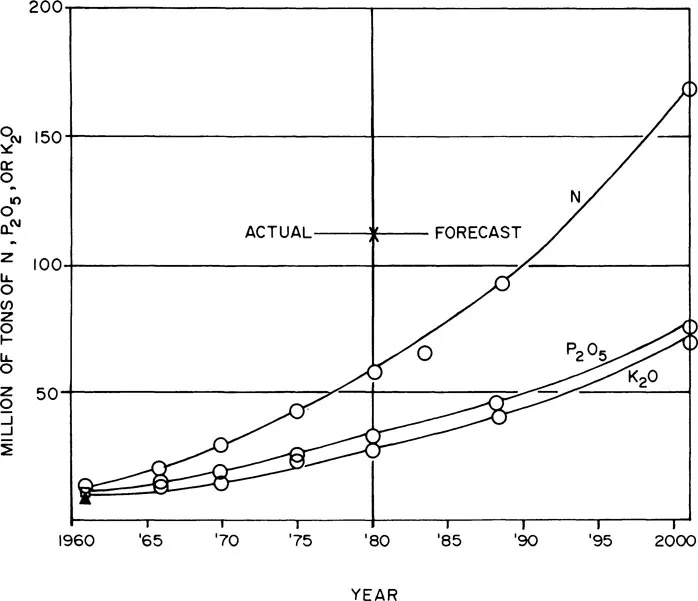

World fertilizer production and consumption are expected to continue to increase, but at declining annual percentages. Table 1 shows projections of world fertilizer consumption from a 1978 UNIDO study (1). Figure 1 shows the world projection by nutrients [N (nitrogen), P2O5 (phosphate), and K2O (potash)] and Figure 2 shows projections by classification of countries, developed and developing.* More recent studies by UNIDO and others imply a slower rate of growth than the 1978 projections.

The projections are for fertilizer “demand,” not for the amount of fertilizer that might be required to produce enough food and fiber to feed and clothe the growing world population. While demand is obviously related to need, it is also related to the cost of fertilizer, the price of the agricultural products that will result from its use, and the ability of consumers to purchase these products.

Up to 1972, the cost of fertilizers declined steadily as advances in technology, increase in size of manufacturing plants, and improvements in distribution more than offset steadily rising labor and construction costs. Starting in 1973, a dramatic increase in construction and raw material costs have reversed this trend.

TABLE 1 Projections of Fertilizer Demand (in millions of tons)a

a Actual consumption reported by FAO.

Source: Second World-Wide Study of the Fertilizer Industry: 1975–2000 (1978) UNIDO. Vienna, Austria.

No further technological advances are expected of a sufficient magnitude to offset the sharply increased cost of plant construction, energy, and raw materials. Increasing the size of fertilizer plants beyond that of present large plants will yield only minor reductions in production costs, which may be offset by increased distribution costs. Therefore, it seems inevitable that the cost of fertilizers will continue to increase unless there are unforeseen technological breakthroughs (which are always possible). However, crop prices have also increased, and in 1980 the fertilizer/crop price ratio was still about the same as in 1971 when fertilizer prices were at their lowest level; so rising fertilizer prices will not necessarily slow the growth in fertilizer use.

FIGURE 1 World fertilizer use projections by UNIDO.

FIGURE 2 World fertilizer use by nutrients, actual and projected.

Future cost increases could be slowed by technological improvements and more efficient operation of production facilities. Perhaps a more hopeful field for improvement lies in more efficient physical distribution, better utilization of applied nutrients, and higher operating rates for existing plants in some countries.

Figure 3 shows recent trends in the spot prices of some popular fertilizer materials f.o.b. port of origin. The graph shows a sharp peak in 1974 which is related to the worldwide grain and fertilizer shortage coupled with the sharp increase in oil prices and the petroleum embargo by Arab countries. After 1974, fertilizer prices dropped but remained above 1972 levels and since 1976 have fluctuated irregularly. Increases in fertilizer prices are sometimes attributed to increased energy costs, especially of petroleum. However, potash and phosphate fertilizers are not energy intensive and they have increased in nearly the same proportion as nitrogen fertilizers which are energy intensive. So fertilizer price increases seem more likely to be the result of general inflation, which may be indirectly caused by rising energy costs along with other factors.

Prices received by farmers for grain have increased about as much as or more than fertilizers, at least in the United States. For example, in 1970 a U.S. farmer could buy a ton of ammonia for the farm-level price of 56.4 bushels of wheat, in 1980 he still could. From 1967 through 1980 prices paid by U.S. farmers for fertilizers increased by 147% while the prices received by farmers for corn and wheat increased by 210% and 194%, respectively. On the international market the price per metric ton of urea (bagged f.o.b. Europe) and wheat were about the same in 1967 (about $75); in 1980 they were still about the same ($230). Since 1980 the price of both urea and wheat have declined.

FIGURE 3 International fertilizer price trends.

Fertilizer Use

The estimated world demand for 2001* is 289 million tons of nitrogen (N), phosphate (P2O5), and potash (K2O) as compared with 108 million tons in 1979, a 2.7-fold increase (Figure 1). Assuming an average nutrient content of 42% (N + P2O5 + K2O), the gross weight of annual fertilizer use would be 688 million tons by the year 2001.

Fertilizer use in developing countries is expected to increase from 31 million tons in 1979 to 104 million tons in 2001 (N + P2O5 + K2O basis). This is a 3.6-fold increase. Estimates are based on probable demand and not on food requirements. It is likely that an estimate based on food requirements for adequate nutrition of an increasing population would be higher for most developing countries and lower for many developed countries. Naturally, any long-range forecast is subject to many uncertainties, and no great accuracy can be claimed for these forecasts. However, they serve the purpose of indicating the order of magnitude of needed expansion in the fertilizer industry, especially in developing countries.

The UNIDO report implies that developing countries as a whole will maintain a nutrient ratio for N:P2O5:K2O of roughly 5:2:1 through the 1979–2000 period, whereas developed countries are expected to continue a ratio of about 1.5:1.0:1.0. Thus, the greater part of the growth will be in nitrogen fertilizer in both groups. The worldwide nutrient ratios should not be assumed to imply an optimum ratio for any individual country; country ratios should and do vary widely according to the needs of their soil, crops, and management. The principal grain crops—maize, rice, and wheat—take up N, P2O5, and K2O in a ratio of roughly 2:1:2. If developing countries continue to use a high nitrogen ratio, soil supplies of other nutrients may be depleted and eventually cause a change to a more balanced ratio. About three-fourths of the K2O taken up by cereal crops is in the crop residue and can easily be left in the field or returned to the field, whereas the major portion of N and P2O5 is in the grain which is less easily recycled. The use of high proportions of N in developing countries may be related to inefficient use (heavy losses), which may be corrected in time.

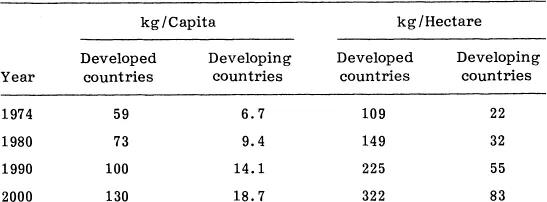

The following table shows present and forecasted fertilizer use in per capita and per hectare terms, in developed and developing countries:

Fertilizer Use on a Per Capita and Per Hectare Basis*

It will be noted that the rate of increase in fertilizer use per capita is substantially less in developing countries than the tonnage rate, and the per capita rate in developing countries will remain far belowthat of developed countries. This is partly because of the relatively rapid population growth rate in developing countries.

Verghese (2) cites these estimates of population growth:

Population (in billions) | ||||

1950 | 1975 | 2000 | ||

Developed countries | 0.86 | 1.13 | 1.35 | |

Developing countries | 1.64 | 2.84 | 4.89 | |

World | 2.50 | 3.97 | 6.24 | |

The rate per hectare in developing countries will be well below the rate at which maximum yields of most crops are obtained, whereas in developed countries the rate per hectare will approach an upper limit of economic effectiveness by the year 2001 unless further advances in high-yielding crop varieties, and cultivation and application methods increase the yield potential.

Fertilizer Production

Production of fertilizers in developing countries as a group has lagged behind fertilizer use. In 1982 production was only 66% of use. As a result, developing countries are...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Foreword

- Preface

- Contributors

- 1. Outlook, Concepts, Definitions, and Scientific Organizations for the Fertilizer Industry

- 2. Nitrogen

- 3. Phosphate Rock

- 4. Potash Mining and Refining

- 5. Thermal Phosphate

- 6. Production of Single Superphosphate with a TVA Cone Mixer and Belt Den

- 7. The Sackett Super-Flo Process

- 8. Wet-Process Phosphoric Acid Production

- 9. Granulation

- 10. Diammonium Phosphate Plants and Processes

- 11. Review of the Production of Monoammonium Phosphate

- 12. Granulation Using the Pipe–Cross Reactor

- 13. Bulk Blending

- 14. Dry Bulk Blending in the Americas

- 15. The Norsk Hydro Nitrophosphate Process

- 16. Controlled Release Nitrogen Fertilizers

- 17. Fluid Fertilizer

- 18. Environmental Regulations

- 19. Concentrated Superphosphate: Manufacturing Processes

- Index