![]()

PART 1

Introduction and assessment

![]()

OVERVIEW OF FORENSIC SERVICES IN THE COMMUNITY

Andrew Bridges and Kasturi Torchia

In the literature of Probation and Youth Offending work the actual word ‘forensic’ is a term that rarely appears. Yet in England and Wales, with individuals who have offended, the core forensic role in community settings has been undertaken by Probation or Youth Offending staff, and they have been doing so for many years. In fact, at the time of writing, in England and Wales well over 200,000 sentenced offenders aged 18 or over are being managed by one of 35 Probation Trusts at any one time, while around 100,000 sentenced offenders aged under 18 are managed by one of 158 Youth Offending Teams or Services, the precise numbers vary depending on which cases are being counted (www.justice.gov.uk/statistics/youth-justice). In Scotland in 1968 the Probation function was taken into the local authority and the then generic Social Work Departments, although in more recent years each local Head of Criminal Justice Social Work has become increasingly subject to central (Scottish) government direction. In Northern Ireland the Probation Board provides Probation services for both young people and adults. In the United States probation is the most common form of sentencing for offenders and two-thirds of offenders are serving community sentences supervised by Probation on any one day (Petersilia, 1997).

But although the word ‘forensic’ has not been part of the traditional language of either Probation or Youth Offending work it is still very much a legitimate way of describing what its practitioners do with around a third of a million individuals at any one time in England and Wales, including the preparation of over a quarter of a million reports for the Courts and related bodies per year.1 In essence they assess individuals who have offended, engage with them, provide forensic practice-based interventions, and review progress and outcomes achieved.

This chapter will provide an introductory overview of these processes as well as an analysis of recent applications, developments and challenges. It is also written not only with the two main statutory community forensic services (Probation and Youth Offending) in mind, but also it recognises the non-statutory, forensic mental health, specialist forensic and substance misuse services that also carry out forensic practice in the community. Important specialist work is done to divert some cases at the arrest stage (i.e. before ever going to court) as well as at the court stage itself – very important for the cases affected, but these are only a tiny proportion of all the cases appearing in court for sentence.

Assessment and review

Throughout this chapter, assessment is defined as both an analysis of ‘what the problem is’ and a statement of what the practitioner proposes to do about it. The formal assessment of each case is made by the practitioner in charge of the case, frequently presented in a formal report prepared for a court appearance (pre-sentence report, formerly social enquiry report) and also on regular occasions for internal purposes. Such an assessment should consist of a reasoned analysis of why this particular individual committed the current offences, and also a plan of what could be done in future that would make further offending less likely.

Assessment takes place in principle when the case ‘starts’, but in practice the reality is often less clear-cut, especially with individuals who may make frequent appearances in court, and in more than one location, resulting in several quick successive ‘starts’ to a case. The initial assessment might therefore take the form of several reports issued to court(s) as well as documents within the organisation’s formal internal record system. Probation and Youth Offending cases should also be formally reviewed by the practitioner in charge of the case at specified intervals – an integral part of the process of ‘assessment’ for the purposes of this chapter.

Probation officers have been preparing ‘probation reports’, later known as ‘Social Enquiry’ or ‘Social Inquiry’ Reports (SIRs), for courts since soon after the Probation of Offenders Act 1907, the role and purpose of the reports ever deepening, and their content widening. Although fairly limited in scope initially, they evolved into the much stronger and more influential role of making ‘recommendations’ of sentences to courts from the 1960s onwards. However, following the Criminal Justice Act 1991 the reports were rebadged Pre-Sentence Reports (PSRs), their format standardised so that they now concluded with ‘proposals’ rather than ‘recommendations’ (Cavadino, 1997).

To promote the more focused role for such reports after 1991, shorter formats were developed, such as ‘Specific Sentence Reports’. To this end the Criminal Justice Act (CJA) 2003 formally declared the purpose of a pre-sentence report to be ‘with a view to assisting the Courts in determining the most suitable method of dealing with an offender’ (s.158 Pre-Sentencing Reports, Criminal Justice Act 2003). Later, PSRs evolved into three separate formats – ‘Standard Delivery’, ‘Fast Delivery’ and ‘Oral’ – for reasons we outline further below.

Alongside these developments, the evolution of the use of structured assessment tools as an integral element in preparing court reports and initial assessments is also evident. For adults the Offender Group Reconviction Scale (OGRS) (Copas and Marshall, 1998), for example, was established in the mid-1990s. It consisted of certain static factors – fixed items of information about each case and not subject to change such as previous convictions and age at first conviction – which enabled a score to be calculated that gave a ‘likelihood of reconviction’.

Although potentially useful for managers, offering a benchmarked profile of the range of seriousness of all the cases being handled, it was of limited value to each individual practitioner. This is in large part due to it being emphatically a ‘Group’ reconviction scale and not a prediction about the particular individual – instead it is an actuarial statement of the percentage of cases in a group of individuals with the same static factors that would be reconvicted in the next two years.

Potentially more useful to the practitioner was OASys (for Probation) and Asset (for Youth cases). These were much more complex to apply, with many more items of information or judgement to record about each case, but they included dynamic as well as static factors and therefore offered the possibility of future ‘improvement’ in the score. Although some practitioners continued to resist the use of these tools, seeing them as a time-consuming bureaucratic burden of limited benefit, the majority now recognise that the benefits both to practitioners and managers outweigh the costs. Most practitioners can complete the structured assessments fairly efficiently, and if they use them wisely, they find that they are aided by OASys’s benchmarking function.

The added benefit of a tool such as OASys is that it can provide a ‘Likelihood of Reoffending’ score at the start of supervision, and then another score later on or at the end of supervision – thereby providing a quantitative measure of progress achieved (or not achieved) during the course of the supervision. This is the advantage for a practitioner of a dynamic scale such as OASys over a wholly static scale such as OGRS – albeit that both scales have different valuable uses overall.

We can highlight two particular issues concerning the assessment aspect of Probation and Youth Offending work: planning as well as analysing and the Assessment conundrum.

Planning as well as analysing

An assessment needs to include both an analysis and a plan, that is both ‘what I think the problem is’ and ‘what I propose to do about it’. However, historically practitioners have generally been much better at doing the analysis than the plan (Bridges, 2011). Practice always varies of course, but a high proportion of reports for Courts in the past have concluded with a brief and vague statement that a period of supervision will ‘enable the causes of the offending behaviour to be addressed’ or words to that effect. This syndrome is clearly evidenced in the findings of inspections of cases by HM Inspectorate of Probation over the last decade (Adult, Youth, and others), in which assessments were seen as fairly strong on analysing the problem and weak on setting out the proposed solution.

However, in very recent years there has been some improvement, with more attention being given to devising much more explicit, coherent, specific supervision plans, a development that needs to continue.

The Assessment conundrum

The ‘Assessment conundrum’ takes a little more explaining. Practitioners face managing the reality that, at a time when efficient use of resources is becoming increasingly topical, some cases require considerably more ‘assessment work’ than others.

Historically, when there was less pressure on resource efficiency, every case was in effect weighted equally, and by implication the time devoted to each case was at each practitioner’s disposal. Standards initially stressed the quantity and quality of work that ought to be undertaken in every case without taking into account at all that the time and resources available to do the work might be finite. Practitioner time was treated as a demand-led ‘free good’.

Once managers formally started giving attention to the amount of work that each case required this highlighted the variety of cases that came the way of Probation staff in particular. Complex cases, for example defendants with long records of violent or sexual harm to others, could require third-party inquiries and analysis of numerous records in addition to the interviews themselves (while in custody or not) and such cases might take over 15 hours of work each.

They are however, a small proportion of the total number of court reports prepared in a year as nearly a fifth of all reports (Adult and Youth) are on cases where there are no previous convictions, and in these cases the Court may have a particular sentence or disposal in mind. An assessment that is ‘fit for purpose’ requires considerably less work in such cases. Therefore different case types require varying quantities of ‘assessment work’ in order to prepare assessments that are ‘sufficient for each case’, focusing specifically on what the Court needs to know (and no more) in order to make a sentencing decision.

As such, one option is that managers could instruct their practitioners to ‘sufficiently assess’, ‘sufficiently analyse’ and ‘sufficiently plan’ to ensure that enough work is done to allow the Court to formulate a record and a sentence (Bridges, 2011). In this way time and resources would be sufficient and proportionate to the type of case being managed. For various reasons, however, this approach is rarely adopted. It is unattractive to many managers because it puts power in the hands of the practitioner and gives very little control to the manager, and it is especially problematic if there are staff with different formal qualifications and skill levels within a local team.

One of the other approaches to tackling this hurdle is a ‘triage approach’ (Holt, 2000; Bonta et al., 2004). It attempts to place control directly with managers and policymakers. Although the term ‘triage’ is borrowed from the world of medicine, where resources are distributed on a need-specific basis to maximise the number of survivors, it is sometimes used in the Probation context to allow managers to put cases into set classifications or categories at an early stage in the assessment process.

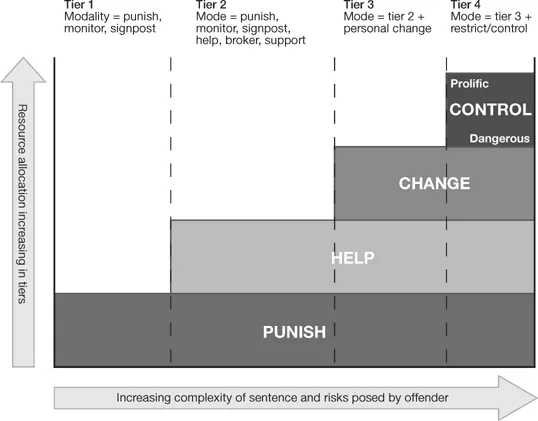

FIGURE 1.1 Tiering system introduced to Case Management in the Probation Service, 2007

One major symptom of this approach was the evolution of the various new forms of court report we outlined earlier: Specific Sentence Reports, Oral, Standard Delivery and Fast Delivery.

In addition to these report formats there have been other innovations that seek to put cases into different categories of ‘work demand’. Figure 1.1 shows the ‘Tiering’ system, introduced to Probation in 2007, in a series of presentations made at the time by senior managers. This was a credible attempt to allocate each case into a resource tier of which a comparable system, called the ‘Scaled Approach’, was introduced for Youth Offending Teams by the Youth Justice Board from 2009.

However, sometimes it is not possible to know how complicated or demanding a case is going to be until you have completed the assessment. In theory one needs to know the outcome of the assessment before knowing which level of assessment to undertake – this is the ‘Assessment conundrum’. It is for this reason that many practitioners have sought to resist the shorter report formats, arguing that every case put back by a court for a report should have a ‘full’ PSR prepared to avoid missing important information. This is a resource-hungry way of managing the potential problem of exceptional cases – instead a much smarter approach is needed. The effectiveness of an organisation is tested by how well it manages such exceptional cases – it also illustrates how the members of that organisation think about their work.

To illustrate, a young male adult with no previous convictions who has committed an offence of driving with excess alcohol might be put back for a report because the Court is minded to impose an unpaid work requirement (formerly community service, now branded as Community Payback) in addition to any financial penalty or costs. On the face of it the case ‘only’ requires an FDR (‘Fast Delivery Report’) and accordingly the same day the defendant might well be duly sentenced to Community Payback.

It could transpire, however, that the man regularly abuses his female partner, and the local Police Domestic Violence Unit has been called to the home on several occasions. Though this information would probably not change the original sentence by the Court, his current conviction being solely for driving with excess alcohol, it should undoubtedly be taken into account in the way that the case is subsequently sup...