- 134 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Today a college degree is needed to ensure an avenue to a decent standard of living. The workplace demands lifelong learning, since most workers will change careers several times before retiring. Meanwhile, attaining a degree is becoming more difficult both in terms of the time required and money. This affects not only individuals but encourages lawmakers to seek alternatives. This book examines higher education programs designed for and delivered to working adult students under a unique for-profit model, one that benefits both taxpayer and student.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

Higher Education for the American Workforce: An Economic Imperative

As the title of this book makes clear, we recommend that these adult-centered universities be organized as for-profit corporations. For-profit universities offer several advantages over nonprofit institutions, among which are the for-profit’s accountability for educational effectiveness, operational efficiency, cost benefits, and the time it takes them to respond to changes in the nation’s education needs.

These for-profit, adult-centered universities are labor but not capital intensive, their facilities can be constructed with private capital, they pay taxes, and they return more to the public treasury than they take out in the form of federally insured loan subsidies available to their students. In short, they are a bargain for the taxpayers.

Human Capital

There is now a social and political consensus that identifies improvement in the knowledge and skills of the workforce as the investment that is most crucial to our nation’s long-term economic success. Given current federal budget constraints coupled with the present institutional structure of American education and training, many workers will fail to gain the needed knowledge and skills. Improving the knowledge and skills of the workforce will require more than simply providing more of the same education and workplace training. Part of the solution will require institutions of higher education that focus on the efficient development of workplace skills and values, particularly those related to worklife-long education and continuous self-improvement.

One of the few areas in which most economists agree is that a nation’s human capital and the new ideas and innovations generated by that human capital constitute a major engine of economic growth. Now that the fastest-growing part of the American economy is neither manufacturing nor traditional services, but the knowledge-sector of the service industry, investments in human capital, particularly in the form of higher education, pay extra dividends. The economic returns from education are both social and personal. They are social in that the benefits of an individual’s education extend to other workers and are diffused throughout society. For individuals, as the data conclusively show, there is a direct and powerful correlation between higher education and higher incomes. Even here, there is a social benefit—the higher one’s income, the higher one’s taxes and the greater one’s contribution to the support of social services.

The American standard of living, the productivity of the American economy and America’s ability to compete in the global economy no longer rest exclusively, or even primarily, on natural resources, capital plant, access to financial capital, or population. These assets are now secondary to the quality of human capital in determining a nation’s economic condition and standard of living. Every industrial nation now has equal access to raw materials; capital plants can be located anywhere in the world; financial capital moves quickly to wherever the returns are highest; and the brute labor of a large population can only compete with brute labor anywhere in the world. The critical competitive advantage that any nation enjoys is now the quality of its human capital. This quality is largely determined by education.

Human capital resides in both individuals and organizations. In individuals, it is their knowledge and skills and how, through their intelligence, creativity, and energy, they apply their knowledge and skills to the improvement of the economy. Organizational or collective human capital resides in groups of all kinds: corporations, government organizations, universities, and so on. It is obviously present in groups of scientists who work together on a problem; it is present in a team of engineers, production specialists, and marketers who work to develop a new product; it is present, to some degree, in almost every group engaged in a common task. Innovations in the form of new scientific concepts, new products, new ways to organize production, and new ways to market and sell goods and services provide the main stimulus for economic growth. Of course, for these innovations to stimulate growth, the products flowing from them must be produced by companies with a workforce capable of developing, producing, and marketing them efficiently and with a level of quality that meets the expectations of the consumer.

Although innovations come from many sources, most of them are produced by our college-educated workers. The contributions of innovators such as Steve Jobs and Bill Gates notwithstanding, almost all scientific and technical innovations are produced by college-trained scientists and engineers, and most other innovations are produced by college-educated managers and professionals, usually working as members of a team. Not only do the college-educated workers, about 25 percent of the workforce, produce most of the innovations, they also make the decisions that determine the level of knowledge and skills possessed by the other 75 percent.

The Economic Lever of Higher Education

For all workers, of whatever occupation and rank, the world of work is no longer a secure place. Employers can no longer hold out the expectation of permanent employment, since survival for most firms depends upon rapid responses to changing markets and this often entails the laying off of employees. Workers face the challenge of up to seven to ten major career changes in a working lifetime. Today, a worker’s security depends upon maintaining the knowledge and skills that all employers find desirable.

Each occupational change requires a different mix of knowledge and skills, usually of increasing complexity. If one expects to prosper with a rising career, worklife-long education is an economic imperative. Without it, one’s career is likely to stagnate, which soon translates into a real decline in living standards. The recent recession that saw the layoff, followed by long periods of unemployment, of tens of thousands of well-educated middle managers and professionals whose repertoire of skills had narrowed to specific jobs is a cautionary tale that should not be ignored. Many of these layoffs arose from the declining cost of capital goods versus labor. Between 1987 and 1990, the index of capital costs rose from 100 to 110, while the index of labor costs rose to 130. Under these circumstances it behooves anyone who hopes for regular employment to gain and maintain the skills needed to add value to production processes based on sophisticated information systems and production machinery.

Although the present may look bleak to many college-trained workers who have lost their jobs, the Bureau of Labor Statistics projects that 41 percent of all job growth to the year 2005 will require managerial, technical, and professional college graduates. The largest number of these jobs will be executives and managers in marketing, public relations, advertising, communications, and labor relations; technical jobs in engineering, communications, and computers; and professional jobs in health sciences and the law.

Income and Enfranchisement

In 1994, only 64 percent of recent high school graduates who were not enrolled in a postsecondary institution were employed; for recent high school dropouts, the situation was even worse: only 43 percent of recent high school dropouts had employment. Those who did find jobs could expect an average entry level wage of $12,500 rising to $16,000 as experienced workers. Furthermore, the lower the wage, the lower the probability the employer will provide health care benefits. Too often a high school diploma has become a one-way ticket into the ranks of the working poor. The economic rewards of a high school diploma are in stark contrast to the economic rewards of a bachelor’s degree, whose bearer will receive, on average, an entry-level salary of $23,000 with no ceiling if the bearer is talented and lucky.1 University graduates are the only group whose members can reasonably expect to have short periods of unemployment and manage to achieve the American dream of earning more than their parents and offering their children the same opportunity.

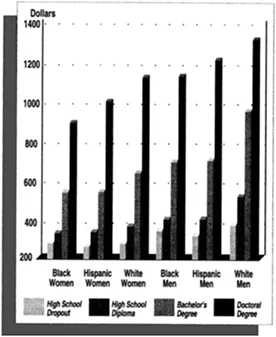

The earnings benefits of higher education for all ethnic groups and both sexes is compelling; for minorities this benefit is truly the avenue of opportunity. Based on 1992 data, a person with some college education will only earn 15 percent more than he or she would as a high school graduate. Completing the degree raises that percentage to 47 percent for a white male and an astonishing 109 percent for a black female. Figure 1.1 shows the education-based earnings advantage for black, hispanic and white men and women.

Higher education is the sine qua non of the good life for nations and for individuals. Consider that:

- In 1980, 25- to 34-year-old white male college graduates earned 16 percent more than their high school graduate counterparts and 39 percent more than those who did not complete high school;

- In 1994, 25- to 34-year-old college graduates were earning 52 percent more than their high school graduate counterparts, and 84 percent more than those who did not complete high school; and

- In 1994, 2.9 percent of university graduates were unemployed versus 6.7 percent of high school graduates, and 12.6 percent of high school dropouts.

FIGURE 1.1

Mean Weekly Earnings, by Race, Gender, and Education Level

Source: U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics

The disparity in the economic status of high school dropouts or graduates and those with a college education is not healthy in any sense for American society since, ultimately, these disparities can only lead to what Benjamin Disraeli described in England in the mid-nineteenth century: “The rich and the poor: Two nations; between whom there is no intercourse and no sympathy; who are as ignorant of each other’s habits, thoughts and feelings, as if they were dwellers in different zones, or inhabitants of different planets.” Today, much the same is true in America. We can amend Disraeli’s characterization to read: “Two nations: One well-educated, affluent, and involved; the other, ignorant, poor and passive”—and the gap is widening. For example:

- In the 1964 presidential election, 25- to 34-year-old college graduates were 14 percent more likely to vote than their high school graduate counterparts, and 34 percent more likely to vote than those who did not complete high school; and

- By the 1992 presidential election, 25- to 34-year-old college graduates were 58 percent more likely to vote than their high school graduate counterparts, and twice as likely to vote than those who did not complete high school.

Summary

Higher education is more important than ever before and will only become more so as greater knowledge and skills are required by a growing number of individuals to function effectively in the increasingly knowledge-driven economy. As this paper will show, the most efficient way to address the issue of increased need for higher education for the workforce is through the development of for-profit adult-centered universities.

Note

1. Based on the field of study, women graduates earned from $18,000 to $30,000 with an average of $20,500. Men earned from $18,900 to $30,900 with an average of $23,900. (See American Council on Education, Research Briefs, vol. 5, no. 2, 1994.)

2

Costs and Access in Higher Education

Higher Education and Budgetary Constraints

The impact of federal and state budgetary constraints on higher education affects both public and private institutions. Reduced federal funding has forced some retrenchment, especially on research universities, but the greatest impact has been on public institutions as they have had to compete for scarce state tax dollars with the demands of welfare, health care, criminal justice, and housing a burgeoning prison population. To a lesser extent, declining state support has also affected private institutions since most receive two to three percent of their budgets from their home states.

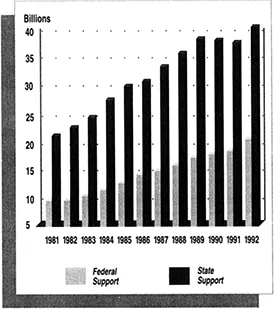

The division of support for higher education between the federal and state governments shows how the burden of higher education has shifted to the states. In 1960, the federal government assumed 16 percent of the financial burden for postsecondary education and the states assumed 19 percent. In 1990, the federal share was down to 11 percent and the state share increased to 23 percent. Until recently this gap continued to widen. Figure 2.1 shows the relative decline in state support of higher education.

This decline is one reason that public institutions have raised fees and tuition and reduced program offerings. Not only has this priced many students, especially those from minority communities, out of the public education market, it has forced colleges and universities to deny entry to tens of thousands of qualified high school graduates.

Financial Constraints on Access to Higher Education

The cost to the nation for higher education has far outpaced the consumer price index (CPI). Between 1981 and 1991, the CPI rose by 50 percent, but even conservative estimates of the costs of higher education show an increase of 88 to 110 percent over the same period. It is data like these that caused the American Council on Education to predict in 1992 that, if this trend is not stopped, a student entering a public college ten years from now will pay $75,000 in tuition alone for a bachelor’s degree. Increases in the cost of attending college reflect more than general inflation in consumer prices. As figure 2.2 shows, the three fastest growing costs during the 1980s were tuition for public colleges and universities, medical care, and tuition for private colleges and universities.

FIGURE 2.1

Federal and State Support for Higher Education

Source: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Stat...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Preface

- 1 Higher Education for the American Workforce: An Economic Imperative

- 2 Costs and Access in Higher Education

- 3 Adult-Centered Universities: Education for the American Workforce

- 4 The Economic and Academic Advantages of an Adult-Centered University

- 5 Critique of Regulatory Constraints

- 6 Federal Action to Create a National Market in Higher Education Services

- Epilogue

- Appendix A

- Appendix B

- Appendix C

- Appendix D

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access For-profit Higher Education by John Sperling in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.