- 523 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

In this new fourth edition, Campbell has revised and updated his classic introduction to the field. Human Evolution synthesizes the major findings of modern research and theory and presents a complete and integrated account of the evolution of human beings. New developments in microbiology and recent fossil records are incorporated into the enormous range of this volume, with the resulting text as lucid and comprehensive as earlier editions. The fourth edition retains the thematic structure and organization of the third, with its cogent treatment of human variability and speciation, primate locomotion, and nonverbal communication and the evolution of language, supported by more than 150 detailed illustrations and an expanded and updated glossary and bibliography. As in prior editions, the book treats evolution as a concomitant development of the main behavioral and functional complexes of the genus Homo– among them motor control and locomotion, mastication and digestion, the senses and reproduction. It analyzes each complex in terms of its changing function, and continually stresses how the separate complexes evolve interdependently over the long course of the human journey. All these aspects are placed within the context of contemporary evolutionary and genetic theory, analyses of the varied extensions of the fossil record, and contemporary primatology and comparative morphology. The result is a primary text for undergraduate and graduate courses, one that will also serve as required reading for anthropologists, biologists, and nonspecialists with an interest in human evolution.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

Introduction

Method and Plan

Scientists do not claim to be in possession of the final truth about the object of their investigations, but scientific research does shift our understanding in the direction of greater truth, by presenting hypotheses which are based on all the evidence that is available to them. Well-corroborated hypotheses are often called theories and such a theory is that of organic evolution. If a hypothesis is fairly general in its presentation, and rests on limited observations, it is difficult to test. A theory such as that of organic evolution with its vast array of detailed evidence, is readily susceptible to disproof.

The theory of evolution has been developed and tested over nearly 150 years as a result of an enormous amount of painstaking research. The evidence that living organisms have evolved over many millions of years is today very strong and convincing. Science builds up such hypotheses or theories on the basis of a vast range of accumulated evidence derived from experiment and observation. Each new piece of evidence has corroborated the central theory. No evidence presently known either falsifies or undermines the theory of organic evolution.

Creationism (mis-named “creation-science”), which posits the separate creation of every species, is based on belief—a system of belief developed without a scientific assessment of evidence. It is a modern version of traditional beliefs which are based on the book of Genesis. Only by the selection of a very limited range of observational evidence can any sort of pseudoscientific case be made for it. It is therefore not a scientific theory but a statement of religious belief, which for support draws on the Biblical texts and the work of a few biologists, where such work can be manipulated to clothe the belief in a pseudoscientific light.

The theory of evolution and a belief in special creation are not rival explanations of organic life that have comparable status as scientific hypotheses; they are quite distinct approaches to the problem of the origin of species.

Although it was seen in the last century as a devastating threat to fundamentalist religious belief, the theory of evolution does not in any way negate the existence of God. It merely describes the mode in which the creation of living species occurred. Because we are beginning to understand some of the mechanics of this process of creation, it is no less full of wonder. As Charles Darwin wrote on the last page of The Origin of Species:

There is a grandeur in this view of life, with its several powers, having been originally breathed into a few forms or into one; and that. . . from so simple a beginning endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been, and are being, evolved.

As part of organic evolution, the phenomenon of human evolution also amounts to a fact. We shall not aim merely at showing that human evolution has occurred, for this has already been demonstrated (see, for example, Le Gros Clark, 1978; Campbell and Loy, 1998). My intention here is to examine the evidence available and to try to describe the transition from animal to human. I will attempt to show how the structure of the evolving organisms has changed over time and how the changes are related to changes in function and behavior. The argument will take the form of a hypothesis about our evolutionary transformation from our animal ancestors to ourselves.

Not only does the presentation of such a hypothesis have a high heuristic value, but it is by the erection and testing of hypotheses that science progresses. They may indeed be tested and found wanting; science demands only that they should be consistent with all the available evidence and at the same time self-consistent. In this book, therefore, we shall turn our backs to the future and look where we have come from. We shall examine the extraordinary processes that have generated us and attempt to understand them.

With the heuristic as well as the scientific value of the exercise in mind, I have attempted to synthesize into a coherent account the evidence now available for the course of human evolution. When we examine the evidence carefully, however, we realize, of course, that directly pertinent facts are limited, inferences from all available data (not a selected part of them) must be made as to what happened in time past. The evidence is often indirect; the whole detailed truth about past events can never be known, but that does not negate the value of building a hypothesis on the basis of all the evidence we can gather about human evolution.

Hypotheses about human evolution rest broadly on four kinds of evidence:

1. Fossils. The first and most important kind of evidence which lies nearest to the prehistoric facts, consists of fossil bones and teeth. The evidence that these ancient fragments furnish is not always directly relevant because we cannot tell whether or not any particular fossil actually belonged to a human ancestor. Indeed, such a coincidence would be unlikely for any particular fossil individual (which may have died without issue), but whether it be the case or not can never be known for sure, even if the individual was mature. However, even if such fragments do not lie on the main and continuing stem of human evolution but are side branches, they can tell us something of the main stem from which they themselves evolved. Their relevance can, however, only be fully understood in the light of the other evidence that we have at our disposal.

Studies of fossil bones and teeth tell us directly of the skeleton and dentition of the animals of which they were a part in the light of our knowledge of the anatomy of living animals. We can, however, make a second inference from their structure. We can make deductions about the size and form of the muscles and nerves with which they formed a functional unit. Muscles leave marks where they are attached to bones, and from such marks we can assess the size of the muscles. At the same time, such parts of the skeleton as the skull and vertebrae give us considerable evidence of the size and form of the brain and spinal cord.

Finally, knowledge of the general structure of the skeleton as a whole will tell us about the animal’s mode of locomotion (swimming, running, jumping, climbing, burrowing, etc.) from which it is not a long step to infer the main features of its environment (marine, fresh water, terrestrial or arboreal).

2. Dating. The age of fossils is essential information needed to elucidate their relationships. Since we are concerned with reconstructing an evolving lineage of individuals and populations, knowledge of their relative age is vital if we are to build up an evolutionary or phylogenetic sequence. The advanced methods used in stratigraphy and radiochemis-try have made it possible to establish both relative and absolute dates for many groups of fossils.

Relative dating methods are based on a thorough knowledge of stratigraphy—the study of the layers or strata which make up parts of the earth’s crust where the rocks are sedimentary (as distinct from igneous) in their formation. Since sedimentary rocks are necessarily laid down with the younger on top of the older layers, fossils in upper layers of undisturbed deposits are younger than those in deeper layers.

Thus the relative age of fossils in a section of an excavation can easily be determined. The main problem arises when related fossils are obtained from different sites some distance apart. In this case the stratigrapher has to correlate the sequence in the two sites to determine the age of one in relation to the other, which may introduce considerable uncertainties. The principle, however, is very important and allowed early paleontologists to develop a whole series of evolutionary sequences, long before the actual age in years of any fossil was known.

Chronometrie or absolute dating depends on being able to determine the age in years of certain geological deposits which may contain fossils, or more often underly or cover fossil-bearing strata. The techniques have been developed as a result of the discovery that certain naturally occurring radioactive elements decay at constant, known and measurable rates into other known elements. Radioactive potassium (K40) and radioactive carbon (C14) are two such elements which decay into argon and nitrogen, respectively. These techniques can be used both directly and indirectly to date fossils in a number of ways, and form an essential basis for the construction of a reliable phylogenetic lineage. There are other methods of determining the absolute age of fossils, some more and some less accurate, but all contribute to understanding the sequence of fossil-bearing strata. It is not appropriate to discuss these methods in this book (see Campbell and Loy, 1998).

3. Environment. Having created a picture of at least some part of our fossilized creature and its age, we can now make a further inference as to its whole biology and its way of life. In the first, place, knowledge of its locomotion will enable us to infer its environment in a broad sense. Supporting evidence derived from a study of the geological context of the fossil may confirm the presence, in the prehistoric times when it lived, of seas, lakes, grassy plains, or forests. Another line of inference begins with the teeth. These may suggest the diet on which the animal fed (herbage, roots, flesh, etc.), and here again we find some indication of how the animal lived.

Next, and most important, other fossils accompanying the hominids can be used to establish a list of species that (in comparison with living forms) will tell us in much more detail of the biological environment in which our ancestors lived. Were the accompanying species (from mammals to mollusks) arboreal, terrestrial, lacustrine, riverine or marine forms? The sorts of climates which then existed as well as the general environment of the fossil community can often be determined. Finally, the plant remains can be examined to produce a list of flora for the site. Plant remains—usually pollen but sometimes seeds and rootcasts—will provide further indication of the climate and environment of the fossil-bearing (fossiliferous) land surface.

In this way, by rather extensive deductions, we can piece together a picture of the whole environment of the extinct animals we are studying (e.g., Andrews, 1979).

4. Living animals. Our interpretations of prehistoric populations of animals are based on one further and essential line of evidence, that of living animals. This fourth kind of evidence, though seemingly remote, will prove of inestimable value. As it follows from the fact of evolution that all animals are related, it is reasonable to deduce that those most broadly similar are most recently descended from a common stock. We must therefore compare the anatomy and physiology of living animals— and especially the monkeys and apes—with that of living humans. This method can also be used to assess the closeness of relationship of different fossils. Fossil remains most similar to a particular living animal may be postulated to be the remains of an ancestor of that animal, or a near relative of that ancestor (see Chapter 2).

In view of the methods of studying human evolution outlined above, it is not surprising that our concern will be mainly with bones and teeth, for they are the only parts preserved as fossils. However, that is not as limiting as might be supposed, since the skeleton is the most useful single structure in the body as an indicator of general body form and function. The teeth, too, are very valuable in assessing the relationships of animals because, apart from the effect of wear, their basic form is not altered by environmental influences during growth. It is a feature of the present study, to infer from the bones and teeth—by consideration of their function—the maximum possible information about the body as a whole and the way of life of the animal. In that way we shall attempt to trace the evolution of the whole human being as a social animal. We shall move from a study of the evolving human body to consider evolving human behavior and human society.

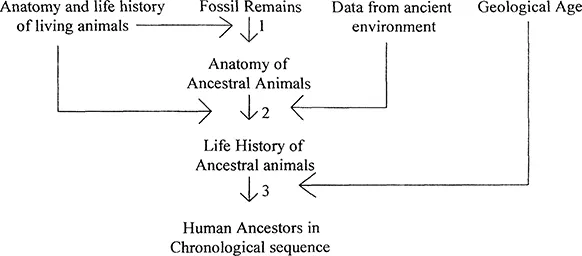

In synthesizing evidence to discover the course of human evolution, we therefore draw on four kinds of data; we study fossil human and animal remains, their geological age, their environment, and related living animals. At one point, we shall be comparing the living primates— our nearest relatives—with ourselves, to gain insight into the differences between us; at another we shall compare their structure with that of fossil remains of our supposed ancestors. The structure of this approach is shown in the accompanying diagram (Fig. 1.1).

The only way to infer the life history of an animal from a few fragments of bone is to investigate the function of those fragments. For example, the form of fossil shoulder and arm bones will be informative only if we try to determine how the muscles were attached to the bones and compare them with those of living animals so as to deduce how the limbs actually worked. We may thus be able to determine the difference in function of our fossil bones from that of the bones of living animals. Was this fossil shoulder joint the type associated with animals that walk qua-drupedally upon the ground or with animals that hang by their forelimbs from trees? An answer to that question gives us immense insight into the whole life history of the animal and such insight is gained from our knowledge of living animals.

Figure 1.1 To describe the lineage of human ancestors in chronological sequence, we study fossil remains by comparing their anatomy with living and other fossil species (2); next, we consider their functional adaptations in light of their anatomy and the evidence of the environment in which they lived (2); and finally, we place them in chronological sequence on the basis of dating (3).

This functional approach involves rather detailed study of the working of each part of the body—in particular the structural parts—and for that reason the method adopted in this book is to study, in turn, the evolution of the different parts. Such an approach presents considerable problems, however, since the body is a single complex mechanism and not merely a collection of discrete mechanisms. Any number of different “functional complexes” can be recognized, but every stage in the subdivision of the animal for descriptive purposes means a loss of truth. We must therefore examine a functional complex in its broadest possible interpretation.

The idea of a functional complex of characters is not new, and it is certainly the most informative and valuable way of analyzing the biology of an organism. A classic study of our origin somewhat along these lines was published in 1916 under the title Arboreal Man by F. Wood Jones. According to this approach, therefore, the body is not simply divided into skull, dentition, vertebral column, arm bones, leg bones, hands, and feet, but into the different parts involved in the different functions of posture, locomotion, manipulation, feeding, etc. This means, of course, that we must face some overlap of subject matter in different parts of the book. It must also be stressed that the meaning of each functional complex itself cannot be understood alone; on the contrary, even consideration of the whole physical body as a single unit is ultimately meaningless without consideration of its psychological and social correlates.

Function, in fact, which describes the structure and operations of an organism or its parts is only half the study of biology. We must also be concerned with behavior, which describes how the organism interacts with the environment (which is everything other than the organism): how the organism actually receives its sensory input, and how it delivers its motor output. The social and cultural behavior of humans, which is the correlate of our complex functions, is in essence no more than an extension and development of the simple behavior of the smallest and simplest protozoa: it is the means of interaction between the organism and the environment that makes possible the biological functioning of each individual and the survival of the species.

Our study of human evolution will therefore be set forth as follows: We begin with an introductory chapter on the nature of evolution, followed by a survey of the background to human evolution—that is, the mammals and our nearest relatives, the primates (Chapters 3 and 4). Then we proceed with a short review of some fossil evidence of early humans (Chapter 5). We then trace in detail the evolution of certain broad functional and behavioral complexes: posture, locomotion, and manipulation (Chapters 6, 7, and 8); sense reception, the head, feeding, and ecology (Chapters 9 and 10); reproduction and society, communication and culture (Chapters 11 and 12). Finally, Chapter 13 will review those different evolving complexes in a time sequence, together with the last stages of the story of human evolution.

It should be stated that the text does not include a complete account of primate anatomy or taxonomy at even the simplest level; such accounts should be consulted elsewhere (Napier and Napier, 1967; le Gros Clark, 1971; Szalay and Delson, 1979; Aiello and Dean, 1990). Our consideration of anatomy will be limited to features that have evolved in such a way as to differentiate us from other primates and in so doing made us the creatures we are. Our aim at all times is to paint a picture that shows how primate biology was modified in the...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- 1 Introduction: Method and Plan

- 2 Evolution and Environment

- 3 Mammals Progress in Homeostasis

- 4 The Primate Radiation

- 5 The Fossil Evidence: The Hominidae

- 6 Body Structure and Posture

- 7 Locomotion and the Hindlimb

- 8 Manipulation and the Forelimb

- 9 The Head Function and Structure

- 10 Feeding, Ecology, and Behavior

- 11 Reproduction, Social Structure, and the Family

- 12 Culture and Society

- 13 Human Evolution

- References

- Glossary

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Human Evolution by Bernard Campbell in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Evolution. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.