![]()

PART 1

Disciplinary frameworks, law, sociology and history

![]()

1

LIMITS AND LIBERTIES

CAM, regulation and the medical consumer in historical perspective

Roberta Bivins

I Introduction

It is the devil’s own science, this medical science…. It matters little which sect we follow. We are marked men and cannot escape. If cold water don’t do for us – warm will – or mercury will – or homeopathy will – or a family physician will – or the common druggist will…. Keep from them as long as you can, and thank God when you get rid of them.

(The Penny Satirist 1842: 1)

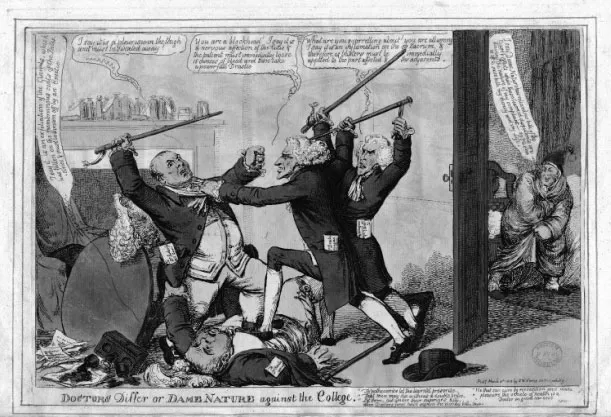

In 1813, a well-known British satirist published an image that, for many of his peers, all too accurately represented the medicine of his age. Titled ‘Doctors Differ or Dame Nature against the College’, it is a scene of mayhem: four bewigged physicians in frock coats are attacking each other with their gold-topped canes, contesting the correct treatment for a wealthy patient (see Figure 1.1). Each offers a prescription more violent than the last, including emetics, bloodletting, sweating and blistering. All contenders are offering prescriptions drawn from the established medical canon of the early nineteenth century: there was no single or even dominant orthodox view of how to diagnose or treat a case. Chuckling in the background, the patient gleefully watches the fray – he has already chosen his healer: ‘Dame Nature’. Cured by nature while the physicians fought amongst themselves, he prepares to escape his would-be doctors, saving ‘both my money and my Life’ (Williams 1813).1

Already a familiar phrase by the seventeenth century, the assertion that ‘doctors differ’ achieved proverbial status in the nineteenth century as an expanding medical marketplace in Europe and North America heightened professional competition for status, clients and authority. As in this image, heated and very public debates broke out amongst those claiming the status of professional healer and, with it, the exclusive right to diagnose and treat ill health. Here, I will offer a historical sketch of the nineteenth-century debates which laid the enduring foundations for contemporary understandings of ‘alternative’ and ‘complementary’ medicine in Britain and the United States. While the battle between ‘allopathy’ and ‘homeopathy’ (and other alternative systems) is well known, I will draw out its most persistent tropes and discuss the ways in which they informed late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century responses to alternative medicine in the US and UK (Bynum and Porter 1987; Cooter 1988; Gevitz 1988; Haller Jnr 2005; Kaufman 1971; Martyr 2002; Nichols 1988). The right of consumers to select therapeutic systems, regimens and individual interventions according to their own preferences and beliefs has been crucial to the survival and diffusion of the practices which have become ‘CAM’. Yet the ability of consumers to do so intelligently and safely has long been questioned, particularly by members of the orthodox medical profession (today, biomedical professionals), seeking restriction of the medical marketplace.

Figure 1.1 ‘The Cold Water Cure’, The Penny Satirist (London, England), Issue 267 (Saturday, 28 May 1842).

Many have interpreted the willingness of consumers to ‘experiment’ with novel or alternative approaches to self-care or healing as an indication of long-term discontent with either the explanatory system or the standard of care provided by established medical professionals and institutions. I will argue that the relationship between CAM use and use of orthodox medicine has, historically, been more complicated; consumer choices have been affected not simply by desperation, discontent or ignorance, but by strong economic and cultural drivers – and indeed, rich traditions of empiricism and self-sufficiency – only some of which have been explored or acknowledged in detail. In other words, while some consumers may have been driven to the use of heterodox medicine by the failures and limitations of the medical establishment, others have actively and positively sought care and cures from beyond its boundaries. For some, such choices have been founded in beliefs inimical to orthodox practices or biomedicine’s insistence on materialism – whether rooted in religion, morality or the enduring appeal of now-discarded medical theories like vitalism. For others, the practicalities of cost and access have been crucial. Finally, some consumers’ preferences have been informed by personal and familial experiences of care and cure outside the surgery, clinic or hospital; or by preferences for domestic self-care and direct control of the medical encounter.

II From quackery to ‘alternative medicine’: the rise of the nineteenth-century systems

With the late medieval and renaissance universities and the retranslation of Greek and Roman medical texts preserved, systematised and improved by Islamic scholar-practitioners, a discernible medical establishment emerged in Europe (and was later replicated to a greater or lesser degree in European colonies and settlements around the world). Spreading from the cosmopolitan Mediterranean basin, this new secular and humanistic medicine – as much a reinvention as a re-discovery of classical learning – rejuvenated learned medicine and its institutions: curricula of instruction; guilds, colleges and faculties of credentialed healers; and some degree of self- and state regulation. (Porter 1997; Siraisi 1990). However, even among the tiny university-educated elite, marked differences in training and epistemology ensured heterogeneity in medical beliefs and practices. Beyond this loose circle, alternative understandings of disease, health and the body persisted (rooted in religion, folk practices, alchemy and astronomy, among others), and a dizzying variety of practitioners provided the vast majority of medical care (Rutten 2011). The sixteenth-century Scientific Revolution introduced new debates and divisions alongside novel experimental and mathematical methodologies, and the seventeenth century saw ever-greater European awareness of the diverse medical systems of China, Japan and the Indian subcontinent (Bivins 2007; Cook 2007; Webster 1975). In part, interest in the latter was a popular response to enduring dissatisfaction with the failures of established medicine: despite their increasing knowledge of anatomy and physiology, doctors remained largely unable to cure even the most mundane of illnesses.

With so many competing sources of medical authority and so few reliable therapies, it is perhaps unsurprising that scholars have described the eighteenth century as the ‘golden age of quackery’ (Gentilcore 2006; Porter 1989). Under regulations dating back to the late-medieval and early modern trade guilds, physicians in many European nations may have been legally entitled to monopolise diagnosis and prescription. In practice, however, their claims were rarely enforced and – with only a minority of patients able to access their services – were perhaps unenforceable (Pelling 2003; Wallis 2008). Even clients who could afford such care often mocked medical obfuscation and bookish theorising. As diplomat and gout-sufferer Sir William Temple wrote of the elite profession in the late seventeenth century, ‘I had ever quarreled [sic] with their studying art more than nature, and applying themselves to methods, rather than to remedies’ (1680: 207).

In contrast, their ‘bastard brethren’, from itinerant nostrum-vendors hawking their potions and pills alongside other market-traders to gentlemanly mountebanks proffering specialist skills to genteel families and courtly elites, offered remedies in plenty. Moreover, while condemning such healers, even some ‘regulars’ admitted that the charlatans proffered their cures with no more deception than was used by their more respectable medical competitors. Kindred in practice, if not equal under the law, both depended on ‘the gullibility of mankind’ (Beddoes 1808: 107, 105). ‘Quackery’ – that is, the commercial promotion, marketing and provision of products, services or treatments hyperbolically claimed (but not proven) to cure illness or engender health – is an abiding presence on the global medical stage. ‘Kwakzalvers’ cried their wares across northern Europe in the sixteenth century, and ‘quacks’ were well-ensconced in the English language by the 1730s. Then as now, however, most quacks did not challenge the medical orthodoxies of their day, but hijacked them in support of their own cures. They operated by subverting or sidestepping the nominal controls on practice optimistically instituted by a growing and increasingly confident, if not yet fully organised, medical establishment. With limited state intervention, and in a marketplace where paying patients still held medicine’s purse-strings, little action could be taken against such profit-seeking ventures. Moreover, only in the second half of the nineteenth century did the established medical profession begin to act against the lucrative practices of nostrum-selling and panacea-patenting among its own ranks. They would thrive, within the profession and without, until the twentieth century.

In the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, however, a new breed of challengers to established medicine emerged: these upstarts sought to replace, rather than to ride the coattails of conventional medical understandings and practices. This was an era marked by explorations of a wide range of invisible forces and substances including magnetism, caloric (1783), oxygen (1774) and galvanism (1791). With so many novel ‘ethereal fluids’ attracting attention and redefining popular and scientific understandings of the natural world, it is perhaps unsurprising that systems explicitly challenging the underlying epistemology of orthodox or ‘regular’ medicine swiftly followed. Between 1775 and 1810, the groundwork was laid for two such systems: mesmerism and homeopathy. Founded by charismatic individuals – respectively, Franz Anton Mesmer (1734–1815) and Samuel Hahnemann (1755–1843) – both systems incorporated the latest scientific understandings of the natural world as full of powerful, if intangible, Newtonian fluids capable of acting on the human body just as oxygen and electricity manifestly did. Thus Mesmer (1784) described his system as rooted in ‘the property which bodies have of being susceptible to the actions of a universally distributed fluid … which serves to maintain the equilibrium of all the vital functions’ and thus to maintain health. This fluid, he believed, was possessed by all living beings, but in unequal measures; those richly endowed with ‘animal magnetism’ could learn to augment and then to use their reserves to stimulate or replenish the defective or depleted stores of the infirm through his methods.

Both systems, too, relied on up-to-date notions of experimental evidence as a source of authority and objective knowledge, and criticised the medical establishment for clinging to unproven theories and practices (including, for example, bloodletting and heroic dosing with mercury and arsenic). Mesmer himself would swiftly fall foul of the experimental system in which he so firmly believed. In what has often – if somewhat anachronistically – been described as a precursor to the randomised controlled trial, Mesmer’s ‘magnetic fluid’ and his practices of ‘magnetising’ were tested in 1784 by a royally appointed Académie de Médecine commission of the scientific great and good (Antoine Lavoisier and Benjamin Franklin both served). When Mesmer’s patients were unable to distinguish between actual and sham ‘magnetism’, he was publicly discredited, and his Parisian practice disintegrated.

Yet the practice of mesmerism persisted despite its founder’s disgrace, spreading to London in the 1820s and 1830s, and from there to North America and the British Empire. In part, mesmerism’s durability derived from its adaptability, and in particular from a new use developed for the trance-like state produced by mesmerism among those susceptible to it. In the absence of reliable anaesthetics and pain-relievers, this new ‘mesmeric anaesthesia’ seemingly allowed surgery (or labour) without pain. While it was largely superseded by the discovery of ether in 1846 and then ferociously purged from ‘regular’ practice, mesmerism continued to be applied in private homes and in theatrical displays, often under the untainted name of ‘hypnotism’. Under that name and stripped of its claims to a material basis, it has since been partially integrated into biomedicine.2 Mesmerism models one trajectory commonly followed by medical ‘alternatives’, over the course of which a given practice emerges, provokes controversy, investigation, experimentation and limitation, and is then absorbed, in part or entirely, into normative medicine.

In contrast, homeopathy blazed a very different trail, one in which the challenging system resists integration and retains a separate identity as an alternative to established medical knowledge and practice. Like Mesmer, Hahnemann did not initially position himself as a medical iconoclast; a university-trained physician and translator of medical texts, he expected to reform medicine from within. Thus, Hahnemann at first simply declared his discovery of two new medical ‘laws’. The first – called ‘the law of similars’ after Hahnemann’s famous phrase ‘similia similibus curantur’ (like treats like) – was, he asserted, based on careful observation of nature and deliberate self-experimentation. Hahnemann reported that those substances which caused the symptoms of a particular disease in a healthy person would relieve those symptoms in their sufferers. He had become convinced of this ‘law’ through an experiment initially constructed to explore the workings of an established medicine: in 1790, Hahnemann deliberately ingested cinchona bark – rich in quinine – and experienced in consequence symptoms of the malarial fevers which that drug famously cured.

Hahnemann’s second principle (much derided both in the nineteenth century and today) was the ‘law of infinitesimals’. Unlike the law of similars, the law of infinitesimals was rooted as much in theoretical reasoning on the metaphysical nature and origins of disease as in observation or experiment (though Hahnemann and subsequent homeopathists did experimentally test the theory). Essentially, Hahnemann believed that disease sprang not from a simple breakdown in the bodily mechanism (which might demand similarly mechanical treatment: for example, purges to vent impurities, or emetics to remove blockages) but from disturbances of the body’s ethereal vital force. Thus treatments needed to act on the metaphysical, rather than the corporeal level. Hahnemann argued that the therapeutic potency of a medicine in this metaphysical realm grew as the physical medicinal substance itself was mixed, diluted and refined (Nichols 1988; Devrient and Stratten 1833). Homeopathists from Hahnemann onwards would later claim inoculation as further evidence supporting both of their new laws (see Hahnemann 1962: section 46, note 47, cited in Nichols 1988: 12).

Hahnemann claimed to have derived his laws and the therapeutic system built around them through reasoned experiment, rather than through either scholarly theory-building or empiricism alone. In this, his ‘new science’ was attuned to on-going debates in the medical community. Most importantly, Hahnemann’s system incorporated the growing faith, shared by medical professionals and consumers alike, in the vis medicatrix naturae – the very healing power of nature that so appealed to the gleeful patient with which this chapter began. Similarly, he accepted and built upon emerging models of disease as ‘self-limiting’. These models proposed that diseases had a natural course through which they would inevitably progress, ending in a ‘crisis’ during which the patient’s ‘dynamis’ or vital force would either be exhausted or be restored to a state of healthy balance.3 In combination, thes...