![]()

1

Introduction

Bodily communication, or non-verbal communication (NVC), plays a central part in human social behaviour. Recent research by social psychologists and others has shown that these signals play a more important part, and function in a more intricate manner, than had previously been realized. If we want to understand human social behaviour we shall have to disentangle this non-verbal system.

We know what these non-verbal signals are:

facial expression

gaze (and pupil dilation)

gestures, and other bodily movements

posture

bodily contact

spatial behaviour

clothes, and other aspects of appearance

non-verbal vocalizations

smell

Each of these can be subdivided into a number of further variables, for example different aspects of gaze – looking while listening, looking while talking, mutual gaze, length of glances, amount of eye-opening, pupil expansion, etc. It is a matter of sheer empirical research to find out what effects, if any, these variables have. For example, head-nods are very important, foot movements are not. We shall describe the detailed working of each kind of signal later.

In fact each of these channels functions in a distinctive way, and there is quite a different story to tell about each of them. Gaze is primarily a channel rather than a signal; facial expression is the most innate; gestures vary greatly between cultures; touch is often taboo; clothes are the most subject to changes in fashion, and so on. And these bodily signals are often quite small, subtle, and unconscious, which gives them an added interest. The correct use of NVC is an essential part of social competence, and of specific social skills; mental patients are usually deficient in this sphere.

The results of this enquiry go beyond the sphere of social psychology. There are fairly radical implications, too, for other areas of study concerned with human behaviour – linguistics, philosophy, politics, and theology, for example. The main point here is to suggest that too much importance has been attached to language in the past; we shall show that language is highly dependent on and closely intertwined with NVC, and that there is a lot which cannot be expressed adequately in words. There are also practical implications in a number of areas-the treatment of mental patients, education, design of communication systems, race relations, and international affairs, for example.

Definitions and Distinctions

Non-verbal communication, or bodily communication, takes place whenever one person influences another by means of facial expression, tone of voice, or any of the other channels listed above. This may be intentional, or it may not be; in the second case we may call it non-verbal behaviour (NVB) or in some cases the expression of emotion, etc.

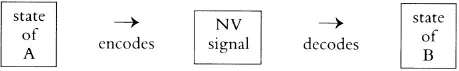

The basic paradigm is as follows:

There is encoding by A of his state, e.g. of emotion, into a NV signal, which may be decoded by B, not necessarily correctly.

There are a number of possibilities here:

- A encodes, and B decodes, using a shared code, e.g. both know that proximity signals liking.

- B decodes incorrectly, either because A was a poor sender or B a poor receiver, or both.

- A sends a deceptive message, which B may or may not be taken in by.

- A does not intend to communicate at all, but his behaviour contains information and B may be able to decode, e.g. perceiving that propping the head up is a sign of boredom.

- A does not intend to communicate, and B decodes erroneously, perhaps using widely held but incorrect beliefs about the meaning of NVC, e.g. that gaze aversion signals deception.

In addition, many NV signals are part of a rapid stream of signals, both verbal and non-verbal, and there is usually communication in both directions. Nevertheless, the encoding-decoding paradigm is a useful one, and enables us to distinguish between research on encoding and on decoding.

Verbal v. Non-Verbal

Verbal behaviour usually consists of speech, but also sometimes of writing, or gestures standing for letters or words. However, speech is accompanied by an intricate set of non-verbal signals, providing illustrations and feedback and helping with synchronization. Some of these are really part of the verbal message itself- the prosodic signals of timing, pitch, and emphasis in particular. Other non-verbal signals are independent of the speech content, including the paralinguistic signals, for example emotional tone of speech. However, non-verbal signals are often affected by verbal coding; symbolic acts or objects used in rituals, for example, may be named or have specific meanings, and patterns of non-verbal behaviour, e.g. styles of behaviour like ‘charm’, ‘dignity’, and ‘presence’ may be verbally categorized. On the other hand some non-verbal signals stand for emotions, attitudes, or experiences which are not easily expressible in words. Last, as noted above, the distinction verbal/non-verbal does not correspond to vocal/non-vocal, since there are hand movements which stand for words, and vocalizations which do not.

Communication v. Unintentional Signs

When a man raises his programme at an auction sale to make a bid, he consciously intends to send a message to the auctioneer; he is using a shared code, and the auctioneer perceives him correctly as a person intending to send a particular message. It is clearly different when an animal or person in a certain emotional state displays visible signs of that emotion, such as trembling or perspiring, which are then perceived by others: this is an observed sign, but there is no intention to communicate. For communication proper there are goal-directed signals, whereas signs are simply behavioural or physiological responses. In communication there is awareness of others as beings who understand the code which is being used.

Unfortunately it is very difficult to decide whether a particular non-verbal signal is intended to communicate or not: as we shall see there are communications which are motivated, without conscious awareness of intention. One criterion is whether or not the signal is modified as a function of the conditions (e.g. when telephoning instead of communicating visibly), or whether the signal is repeated if it has no effect. Another criterion is whether or not the sender varies his signal in order to elicit the correct response from the receiver (Wiener et al. 1972).

However in many cases non-verbal signals are a mixture of the two. Facial expressions of emotion, for example, consist partly of the spontaneous expression of emotion (i.e. NVB), partly of attempts to control it, to conform to social rules, or to conceal the true emotion (NVC). It could be argued that the spontaneous expression of emotions is part of a wider system of communication which has evolved to facilitate social life. So we will call it all non-verbal or bodily communication.

Conscious and Unconscious

How far are people consciously aware of sending and receiving these signals? A person may succeed in dominating another by the use of such non-verbal signals as standing erect, with hands on hips, not smiling, and speaking loudly. A person may indicate that he has come to the end of a sentence by looking up, and returning his hand to rest, or indicate that he wants to go on speaking by keeping a hand in mid-gesture. In none of these cases are those involved usually aware of the signals being used or of what they mean. They are probably all cases of communication, but unconscious on both sides. We shall consider the special features of consciously controlled behaviour later.

Similar considerations apply to the perception of signs: a girl is attracted by a boy, so her pupils expand, acting as a signal which in turn attracts him, though he is not aware that this signal is doing it. Most animal communication appears to be like this. An animal resonds to a situation, and this response triggers off responses in other animals. Although these signals do not appear to be goal directed in most cases, it can be argued that they are part of a goal-directed evolutionary process that has produced this signalling system.

Again this distinction between conscious and unconscious signals is a matter of degree and there can be intermediate degrees of conscious insight. For example, a person may successfully communicate his social status by the clothes he wears, but verbally categorize these clothes only as ‘nice’, or ‘suitable’. Other cases of unconscious communication occur in primitive rituals and have a powerful emotive and possibly therapeutic effect without anyone being consciously aware of this symbolism.

We can distinguish between communications where the sender and receiver are aware or unaware of the signal, as follows:

| Sender | Receiver | |

| aware | aware | verbal communication, some gestures, e.g. pointing |

| mostly unaware | mostly aware | most NVC |

| unaware | unaware, but has an effect | pupil dilation, gaze shifts, and other non-verbal signals |

| aware | unaware | sender is trained in the use of e.g. spatial behaviour |

| unaware | aware | receiver is trained in the interpretation of e.g. bodily posture |

Some psychoanalysts have claimed that unconscious impulses can be seen in the postures and gestures of patients. Some popular books have provided advice on, for example, how to judge another person’s sexual availability. We shall examine these claims later.

Five Types of Bodily Communication

NVC has several different functions:

Expressing emotions, mainly by face, body, and voice. To understand this takes us to the heart of the psychology of emotion.

Communicating interpersonal attitudes. We establish and maintain friendships and other relationships mainly by NV signals, such as proximity, tone of voice, touch, gaze, and facial expression, much as animals do.

Accompanying and supporting speech. Speakers and listeners engage in a complex sequence of head-nods, glances, and non-verbal vocalizations which are closely synchronized with speech and play an essential part in conversation.

Self-presentationis mainly achieved by appearance and to a lesser extent by voice.

Rituals. NV signals play a prominent role in greetings and other rituals.

Different Types of Signal

Some NV signals are like words in being discrete, for example particular gestures, while others are continuous, like proximity or loudness of voice. Some NV signals are like words in being arbitrarily coded, but others are ‘iconic’, i.e. they are similar or analogous to their referents. Examples of iconic coding are showing the teeth in anger, or proximity for affection; examples of arbitrary coding are most aspects of clothes or appearance, e.g. style of hair, to show group membership. Some signals have invariant meanings, others have a probability of meaning something. Loudness of speech has a probabilistic relation to extroversion; specific gestures may have invariant meanings.

Language itself is discrete, arbitrary, and invariant in coding, and some kinds of NVC resemble language in these respects, especially gestures. I am referring here to common ‘emblems’ (see p. 191) such as the hitch-hike sign and waving ‘hello’; sign language proper is not really NVC at all, and we shall not discuss it in this book. A number of investigations have emphasized the similarity between NVC and language and have designed their methods of research accordingly (p. 17f.).

However, a great deal of NVC is not like language in these ways: proximity and amount of gaze, for example, are continuous, iconic, and probabilistic. And it is not simply a case of there being two kinds of NV signals, since some are mixed on these three criteria; facial expressions are continuous, mostly arbitrary, and probabilistic, for example (Scherer and Ekman 1982).

There is physiological evidence that there are at least two levels of brain mechanisms which are responsible for NVC. The more primitive brain centres govern spontaneous emotional expressions, while higher brain centres control expressions, to conform to social rules, or to conceal immediate feelings, for example (p. 124).

Human v. Animal NVC

It was noticing the similarities between men and monkeys which gave birth to NVC research. Animal behaviour is mainly innate and its evolutionary origins can be traced, so here is part of the explanation of human NVC.

However, men are very different from monkeys. The most obvious difference is that we use language. Animal communication is nearly all about their internal states and intentions, whereas much of our conversation is about people, thing, or events outside ourselves, the past and the future. The use of language has generated a whole new set of NV signals – for accompanying and elaborating on speech, providing feedback, and managing the synchronizing of utterances (see Chapter 7). It is interesting that we have also retained the older uses of NVC – for communicating emotions and managing interpersonal relations.

The second main difference between men and animals is the extensive build-up of human cultures over the course of history. We shall discuss later the detailed ways in which NVC varies between Arabs, Japanese, Italian, Africans, and others (see Chapter 4). There may be quite ...