- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Nature Writing

About this book

In this comprehensive study of the genre, Don Scheese traces its evolution from the pastoralism evident in the natural history observations of Aristotle and the poetry of Virgil to current American writers. He documents the emergence of the modern form of nature writing as a reaction to industrialization. Scheese's personal observations of natural settings sharpen the reader's understanding of the dynamics between author and locale. His study is further informed by ample use of illustrations and close readings core writers such as Thoreau, John Muir, and Mary Austin showing how each writer's work exemplifies the pastoral tradition and celebrate a spirit of place in the United States.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Topic

LittératureSubtopic

Critique littéraireChapter 1

Overview Pastoralism: Illustration and Definition

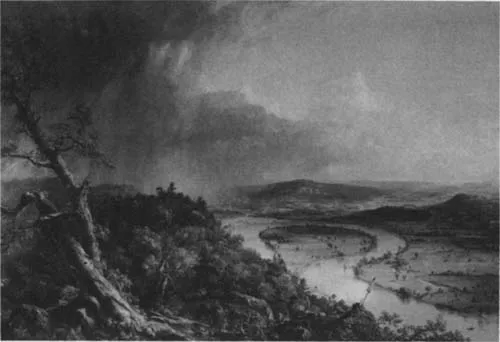

In 1836, at the National Academy of Design in New York City, the artist Thomas Cole exhibited a landscape painting based on a sketch he had first done in 1833: View from Mount Holyoke, Northhampton, Massachusetts, after a Thunderstorm (The Oxbow) (Figure 1). The work features a view from a vantage point that was fast becoming one of the most popular sites on the American “grand tour.” In 1833 Cole first made a pilgrimage to the summit of Mt. Holyoke, 1,070 feet above the Connecticut River, from which point observers were struck by the natural curiosity of a river appearing to nearly double back on itself.

But it was not only the oddity of the oxbow that attracted spectators. The view provided an outstanding example of the sublime—a phenomenon, according to the 17th-century English philosopher Edmund Burke, “productive of the strongest emotion which the mind is capable of feeling.” In delineating a theory of the sublime Burke adds that “astonishment… is the effect of the sublime in its highest degree; the inferior effects are admiration, reverence, and respect.” In the 19th century, significant numbers of middle- and upper-class Americans, self-conscious

Figure 1: The Oxbow (The Connecticut River near Northampton), by Thomas Cole (1801–1848).

Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Gift of Mrs. Russell Sage, 1908. (08.228).

Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Gift of Mrs. Russell Sage, 1908. (08.228).

about the newness and alleged inferiority of our country's art, sought out local examples of the sublime, determined to prove to Europe that we as a nation could produce creative work that was commensurate with our magnificent natural environment. That the oxbow was seen in these terms is confirmed in its description by a tourist in 1833, who wrote that the view of the river was a “scene of sublime beauty … one of the most magnificent panoramas in the world.”1

Cole's depiction of the river in 1833 underwent a significant transformation by the time the large canvas (51.5 by 76 inches) was executed three years later. He exaggerated the panoramic qualities of the scene, increased the spatial depth, heightened the elevation of the mountains, and contrived to divide the canvas in half by introducing a thunderstorm on the left side. A viewer of The Oxbow (which since 1908 has hung in New York's Metropolitan Museum of Art) gazes at the following landscape: in the left foreground stands a weather-blasted tree, rendered in minute detail; behind it a thunderstorm passes over a forested ridgeline and, one assumes, the river valley; a flock of large birds hovers in front of the rain falling from the clouds. In the right rear are forested mountains; closer are cultivated clearings marked by farmhouses with smoking chimneys. In the right lower corner are signs of humans along the river, perhaps part of a ferryboat operation. In the right foreground is an artist, turned toward the viewer of the painting, with an easel and canvas; to his right on a rock outcropping is his parasol.2

How are we to interpret this panorama, which is now regarded as “probably the most renowned of all Hudson River school landscape paintings,” “the most meaningfully devised American landscape work up to that time,” “one of the established icons of American art”? First of all, the painting clearly sets up a number of tensions or polarities: light versus dark, civilization versus wilderness, a rural versus a wild landscape. The presence of the artist in the painting suggests further possibilities for interpretation. He is well-ensconced in the wilderness portion of the scene, but he also functions as a mediator between view and viewer, nature and art. In nature but also dwarfed by nature, relatively inconspicuous, he appears to be conscious of his dual role as dweller in and creator of nature.3

The mountain in the center of the canvas, on whose forested slopes are carved the Hebrew letters for Shaddai, or “the Almighty,” adds further to the interpretive possibilities. Is Cole coyly suggesting the existence of a new covenant between God and America, “nature's nation”? Overall, is the artist alluding to the process of “manifest destiny,” since the painting follows the classic pattern of domesticating the wilderness as America proceeds westward?4

The painting's ambiguity is enhanced if one also considers that the river itself forms a question mark, suggesting that this rendering of a page from the “book of nature” is open to endless interpretation.

It may seem odd to open a study of nature writing with an analysis of a painting. But this methodology is appropriate, I think, for a number of reasons. Cole himself was a nature writer of sorts, recording his thoughts and impressions in writing while out in the field. He was also an influential spokesperson for the concept of wilderness in American culture, as I will demonstrate subsequently in a reading of his famous “Essay on American Scenery.” Furthermore, The Oxbow was exhibited at a critical time in the history of landscape aesthetics: that same year, Ralph Waldo Emerson's Nature was published, a work now seen as the cornerstone of the transcendental movement in America and widely recognized as a major influence in the development of modern nature writing. Also at this time, landscape tourism was becoming firmly established as a middle-class economic activity, thanks to the completion of the Erie Canal in 1820 and the emergence of tourist sites in the northeast—the Catskills Mountain House, the White Mountains of New Hampshire, Niagara Falls. There was a significant overlap in the audiences for the paintings of the Hudson River school and the writings of Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, James Fenimore Cooper, and others.5

Most important, I open with an examination of Cole's painting because it is a visual representation of the pastoral, a tradition integral to the development of nature writing. The pastoral as a literary type harks back to ancient Greece and the poetry of Theocritus and Virgil, featuring herdsmen (typically shepherds) in a bucolic setting caring for their animals and singing of the benefits of rural over urban life. It evolved over the centuries into a complex form, especially during the 1800s, when romantic writers confronted the forces of modern industrialization. One of the foremost scholars of modern pastoralism is Leo Marx, who defines it as “the desire, in the face of the growing complexity and power of organized society, to disengage from the dominant culture and to seek the basis for a simpler, more harmonious way of life ‘closer’ (as we say) to ‘nature.’” At the heart of the pastoral, no matter what its historical context, is a preference for the apparently “simple” world of “nature” (traditionally understood as the nonhuman realm) over the complicated life of “civilization.” Writers (and artists) of this tradition have typically represented or constructed nature as a retreat or sanctuary, as Arcadian garden or wilderness refuge.6

As The Oxbow illustrates, pastoralism also entails a process of containment which, according to another important critic, Herbert Lindenberger, “defines itself through the forces with which it sets up tensions.” Once the protagonist has completed the move from civilization to nature, pastoralist writing “takes the form of an isolated moment, a kind of island in time, and one which gains its meaning and intensity through the tensions it creates with the historical world.” In Cole's painting, for example, the artist—from his idyllic mountainside retreat in the liminal space bordering the dark, wild terrain and the sunlit, cultivated landscape—can witness (in an allegorical reading) a collision of the forces of wilderness and civilization, symbolic of the transformation of nature that was occurring on a wide scale in 19th-century America. The presence of both wilderness and farmland in The Oxbow pertains to another important point made by Lindenberger. He distinguishes between two different kinds of pastoral: “the ‘soft’ pastoral of cultivated landscapes and social communion and the ‘hard’ pastoral of wind-swept slopes and total solitude.” Though his focus is on Shakespearean and European romantic examples of pastoral, Lindenberger's discussion has been applied to the American tradition as well.7

In fact, I would argue that American pastoralism presents the fullest, most compelling version of the tradition, both in the number and kinds of forces it contains and in the diversity of “soft” and “hard” pastoral versions it has represented. Diagram 1 shows some of the more important tensions or polarities to be found in the works of nature writing that I will discuss individually.

Pastoralism has flourished as a genre and a cultural activity because it contains and, through a dialectic, attempts to resolve

| Wilderness | Civilization |

| Nature | Culture |

| Wildness | Domestication |

| Re-creation | Recreation |

| Unconsciousness | Self-consciousness |

| Biocentrism | Anthropocentrism |

| Native American cultures | Euramerican culture |

| Traditional environmentalism | Radical environmentalism |

| Antimodernism | Progress |

key tensions manifest in the culture at large. One of these tensions is the conflict between civilization and wilderness, the result of society's traditional definition and encouragement of “progress” at the expense of the nonhuman world. At heart pastoral writers are antimodernists who employ the pastoral to tell of their “escape to”—a less pejorative way to put it might be “quest for”—a particular place in order to celebrate a return to a simpler, more harmonious way of life “closer to nature”; and to present to their audience, from the vantage point of the predominantly nonhuman world, the pleasures and privileges of living a kind of border life.

PASTORALISM AND NATURE WRITING

What is the relationship between pastoralism and nature writing? As I will detail shortly, modern nature writing—the primary focus of this study—emerged in response to the industrial revolution of the late 18th century and has become without question the most popular form of pastoralism. The typical form of nature writing is a first-person, nonfiction account of an exploration, both physical (outward) and mental (inward), of a predominantly nonhuman environment, as the protagonist follows the spatial movement of pastoralism from civilization to nature. In its key emphases, nature writing is a descendant of other forms of written discourse: natural history, for its scientific bent (the attempt to explain the workings of the physical universe over time); spiritual autobiography, for its account of the growth and maturation of the self in interaction with the forces of the world; and travel writing (including the literature of exploration and discovery), for its tracing of a physical movement from place to place and recording of observations of both new and familiar phenomena.8

THE GEOGRAPHY OF NATURE WRITING

How to describe the place to which nature writers escape is a problem fraught with ethnocentric implications. “Wilderness” has been the traditional designation, connoting land unaffected by humans. However, given the insights provided recently by environmental historians, the standard term—or at least what it has come to signify—no longer suffices, for archaeological and historic evidence indicates that portions of the North American continent were manipulated by Paleo-Indians at least 10,000 years prior to European discovery and settlement. It is no coincidence that the popularity of wilderness grew during the 19th century even as “wild” lands and Native American populations drastically shrank; “wilderness” thus became an invention, a social construction, to suit the ideology and policies of the dominant postcolonial culture. Yet wilderness retains such resonance that a satisfactory synonym is difficult to find. In part this has to do with legal authorization (namely the Wilderness Act of 1964): the very word “wilderness” is now officially recognized. I use the term, then, to distinguish it from what we generally understand as rural, urban, and suburban space.9

The cultural geographer J. B. Jackson has clarified the debate over nomenclature by distinguishing between wilderness and landscape. He defines “landscape” as “synthetic space, a man-made system of spaces superimposed on the face of the land.” As Diagram 2 illustrates, the inner city, with its totality of built environments and minimum of space unaffected by humans, qualifies as the ultimate form of landscape; the suburbs constitute a form of the soft pastoral with managed vegetation and modicum of green space; the farm, with its manipulation of land through cultivation but wit...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Praise for NATURE WRITING

- Half Title

- GENRES IN CONTEXT

- Full Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Chronology

- Chapter 1 Overview

- Chapter 2 Walden, Ktaadn, and Walking

- Chapter 3 My First Summer in the Sierra

- Chapter 4 The Land of Little Rain

- Chapter 5 A Sand County Almanac

- Chapter 6 Desert Solitaire

- Chapter 7 Pilgrim at Tinker Creek

- Chapter 8 Conclusion

- Bibliographic Essay

- Recommended Titles

- Notes and References

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Nature Writing by Don Scheese in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Littérature & Critique littéraire. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.