![]()

CHAPTER 1

The Classification of Developmental Disorders: An Overview

Stephen R. Hooper

University of North Carolina School of Medicine

Although the classification of childhood and adolescent psychiatric disorders is relatively recent, the classification of developmental disorders is an even newer enterprise. As will be seen, however, whereas there have been several efforts to place psychiatric disorders into various kinds of nosological frameworks, as illustrated by the various versions of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (e.g., American Psychiatric Association, 1987) and the International Classification of Diseases (e.g., World Health Organization, 1978), efforts to classify developmental disorders have been loosely organized and highly varied. The various psychiatric nomenclatures have attempted to include developmental disorders in their systems, particularly with the advent of the multiaxial system, where most developmental disorders are separated from the primary psychiatric disorders (e.g., in the DSM-III-R, developmental disorders are placed on Axis II), but historically it is clear that little attention has been devoted to the classification of developmental disorders as a whole.

In contrast to the recent increased interest in childhood and adolescent psychiatric disorders over the past two decades, there appears to be a long history of active interest in general (e.g., autism, mental retardation) as well as more specific (e.g., specific reading disorder) developmental disorders of childhood and adolescence. For example, although the actual term learning disability was not coined until the middle 1960s, case descriptions of children with unusual but fairly specific learning profiles were presented in the 1800s. Similarly, issues with respect to the discrimination between idiocy and insanity were debated as early as the 1700s, with the diagnostic construct of mental retardation being one of the current results of those early debates. Unfortunately, however, outside of efforts by groups primarily interested in psychiatric classification, there have been few formalized efforts to organize the spectrum of developmental disorders.

As noted in this volume’s companion work (Child Psychopathology), the classification of childhood and adolescent psychopathology has evolved as a result of attention devoted to issues surrounding the diagnostic criteria pertinent to specific disorders. In particular, the scientific parameters of classification systems have been emphasized, and the development of objective instrumentation has improved the diagnostic capabilities of clinicians and researchers. For the spectrum of developmental disorders, this scope and sequence of activities have not occurred in any organized fashion, and consequently there has yet to be a functional nosology for developmental disorders. This has not necessarily been the result of lack of interest, poor research, or general oversight, but rather it appears to be due more to the significant dynamic complexities inherent in studying behavior, particularly the behavior of children. Further, it seems that definitional issues have plagued many of the developmental disorders.

This volume and its companion, Child Psychopathology, are devoted to presenting expert appraisals of the scientific merits of the child and adolescent diagnostic categories described in the DSM-III (American Psychiatric Association, 1980) and in the DSM-III-R (American Psychiatric Association, 1987), with a particular eye toward proposing refinements in the current diagnostic criteria based on the available empirical literature. For the developmental disorders, in particular, this information should be helpful in refining their diagnostic criteria and, consequently, increasing their reliability, validity, and clinical utility.

This chapter provides an overview of the classification issues relevant to increasing our understanding of the wide array of developmental disorders that have been proposed. General classification concerns are presented, and specific classification rules are discussed. Classification efforts for selected developmental disorders relevant to this volume, and issues related to their inclusion within a psychiatric classification framework also are presented.

CLASSIFICATION ISSUES AND MODELS

Classification Issues

Achenbach (1985) noted that “classification refers to any systematic ordering of phenomena into groups or types” (p. 151). He made a distinction between a general classification and a taxonomy, suggesting that the latter term should be reserved for classifications that “reflect intrinsic differences between cases assigned to different classes” (p. 151). It should be clear, however, that these “intrinsic differences” can be defined by any number and/or combination of parameters, such as etiologies (e.g., neurological), specific behaviors (e.g., overactivity), physical characteristics (e.g., blue eyes), and research or clinical goals, all having the single purpose of differentiating between the specific cases in a regulated fashion. Given the elusive nature of etiological agents in many forms of psychopathology, most of the modern attempts at classifying childhood and adolescent psychiatric and developmental disorders have depended largely upon a descriptive approach for determining a taxonomy for these disorders.

The Pros and Cons of Classification. Despite these concerns, there are a number of benefits that can be derived from an adequate classification system. For example, Blashfield (1984) noted that an adequate classification system can provide the vernacular necessary for professionals in the field to communicate with each other efficiently and effectively. Further, the taxonomic aspects of the system should provide relevant information pertaining to number and kind of symptoms, prognosis, treatment selection, response to treatment, comorbid conditions, and perhaps etiological possibilities. Finally, Blashfield described the importance of the interrelationship between adequate classification efforts and theory formulation with respect to selected disorders (Hempel, 1965). Similarly, other investigators have called for any classification system to have the following characteristics: (a) be simple, (b) be based on widely used variables and operational definitions, (c) reflect the prevailing clinical, political, and theoretical views within the field, and (d) be easy to use (Goodall, 1966; Kavale & Forness, 1987).

In contrast, some investigators have asserted potential concerns for even using a classification system. In the 1940s, Huschka (1941) advocated for an idiographic approach as he believed that individual differences would be masked by classification efforts and, subsequently, would hinder the development of our understanding of disorders. More recently, Szasz (1961, 1978) described mental illness and psychotherapy as “myths” and stated that these terms lacked meaning and that their use would contribute to significant social stigma in the patient for whom a specific diagnosis and treatment were applied. Although these concerns should be heeded, it would seem that the “pros” of an adequate classification system far surpass the “cons” (Kendall, 1975; Weiner, 1982) and that any related negative effects (e.g., social stigma) likely arise secondary to ignorance, misapplication, and/or abuse. Taken together, these pros and cons suggest the importance of pursuing classification efforts in an active, organized, and scientific fashion.

Reliability, Validity, and Clinical Utility. As Cantwell (1988) and others (e.g., Last & Hersen, 1987; Skinner, 1986) have noted, issues of reliability, validity, and clinical utility are paramount to the development and ultimate utility of any classification scheme. In part, the integrity of these parameters are based on the following: (a) the preciseness of the operational definitions used, (b) the nature of samples studied, (c) how well the samples are marked (i.e., age, gender, socioeconomic status, etc.), and (d) developmental considerations (Hooper & Willis, 1989). Needless to say, these descriptive issues have not been addressed thoroughly for many of the developmental disorders.

Further, even if the preceding considerations have been carefully described, the reliability of any diagnosis must be determined. If the reliability is low, or if the reliability has not yet been determined, then the usefulness of the diagnosis in terms of etiology, prognosis, and treatment will be meaningless. Quay (1986) noted that the assignment of an individual to a specific diagnostic category must be relatively consistent. This consistency should be noted within and between clinicians as well as over time. The importance of obtaining good reliability for specific diagnoses becomes even more crucial when one recognizes that reliability will set the upper limits on validity.

Relatedly, the determination of validity contributes to the usefulness of any classification system. For example, specific diagnostic categories should be distinguishable from one another and inherently related to the behaviors or constructs used to define them (e.g., specific reading disorders). As Quay (1986) aptly noted, the validity of any single diagnosis within a classification system should determine the utility of the vernacular necessary for professional communication; its accompanying list of symptoms; relevant information pertinent to etiology, prognosis, and treatment; comoroid conditions; and theory formulation. Blashfield (1984) echoed similar contingencies.

Another important feature of any classification system is its clinical utility. This feature rests in part upon its reliability and validity, but it also is determined by its comprehensiveness. Although the comprehensiveness of a classification system always should be balanced with issues of parsimony, how well any system covers the range of possible problems is important, particularly from a clinical perspective. Further, simply because a classification system is comprehensive does not guarantee that the issues of reliability and validity have been addressed in a satisfactory manner. For example, despite the fact that the DSM-III-R (American Psychiatric Association, 1987) includes more developmental disorders than its predecessor (i.e., DSM-III), field trials obtained reliability estimates only for the developmental disorder of Autism. Similarly, for the DSM-III (American Psychiatric Association, 1980), field trials were conducted for the developmental disorders of mental retardation, pervasive developmental disorders, and specific developmental disorders, although kappa coefficients were somewhat variable. Further, Rutter and Tuma (1988) and Blashfield, Sprock, and Fuller (1990) noted that the DSM-III-R contains more diagnoses than can be justified either statistically or clinically; therefore, comprehensiveness in and of itself should never be the sole criterion for determining the clinical utility of a classification system.

Classification Models

To date there have been two general approaches aimed at classifying children with developmental disorders and other forms of psychopathology into groups based on their intrinsic characteristics. One approach, the clinical-inferential approach, has depended largely on the clinical observations of professionals in the field. Although not systematic or scientific by design, the clinical-inferential approach creates a classification scheme that is hypothesis-driven, but typically these hypotheses are not tested directly. Quay (1986) noted that “usually it is authority, not proof, that is the benchmark” of these systems. The DSM and ICD systems were based on the clinical-inferential approach, although more recent efforts have attempted to address the need for these systems to attain more satisfactory scientific standards (Blashfield et al., 1990; Cantwell & Baker, 1988; Dingemans, 1990).

Although classification models derived from these efforts tend to make intuitive sense, there are inherent difficulties with the clinical-inferential approach. Generally, this approach suffers from methodological weaknesses, limited data-reduction strategies, and questionable validity. Further, the clinical utility of classification schemes based on this approach appears limited, particularly given the numerous interacting variables that can be associated with developmental psychopathology.

Prior to the emergence of high-speed technological assistance, the clinical-inferential approach dominated classification efforts in childhood and adolescent psychopathology; however, with the ready availability of advanced computer technologies, many of the problems manifested by the clinical-inferential approach can be addressed effectively by empirical classification techniques. Generally, these techniques are based on a quantitative view of behavior that attempts to derive “prototypic” profiles of psychopathology as opposed to all-or-none categories (Achenbach, 1985). This approach has been illustrated effectively by Achenbach (1985) in the development of a dimensional classification system for childhood and adolescent psychopathology, and it has been used to establish the heterogeneity of specific developmental disorders (Hooper & Willis, 1989; Rourke, 1985).

Although this approach may appear superior to the clinical-inferential approach, the empirical approach to classification is not without its own drawbacks. The ease with which multivariate classification techniques manage data is seductive in that it leaves the door open for investigators to fall prey to “naive empiricism.” Clearly, the adequacy and strength of models derived by empirical classification methods are influenced by many a priori clinical decisions, including those regarding theoretical orientation, sample selection, and variable selection. For example, if the sample is not well marked, and the dependent variables are not selected on the basis on theoretical underpinnings, then the dimensions or groupings that emerge from the empirical analyses may not have much meaning when applied to other populations or settings. Further, the empirical derivation of dimensions stipulates the existence of these dimensions, but it does not stipulate their significance. Whether these dimensions relate significantly to etiological factors or treatment issues is what will determine their ultimate utility. Lastly, the development of any empirically based classification model also should strictly adhere to standards of reliability and validity.

The clinical-inferential and empirical approaches represent the major strategies for classifying childhood and adolescent psychopathology. In addition, specific classification models and guidelines have been proposed in an effort to control the number of concerns expressed previously for both of these approaches. Several of these models and guidelines have been proposed by Cantwell (1975), Skinner (1986), and Blashfield et al. (1990) in order to define parameters for the development of a classification scheme. Although other general models have been proposed for specific developmental disorders (e.g., Adelman & Taylor, 1986), these models and guidelines are believed to be representative of the major issues important to general classification efforts in childhood and adolescent psychopathology.

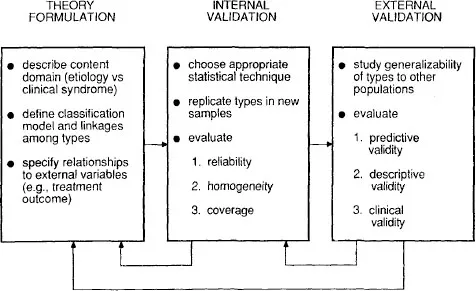

FIG. 1.1 Conceptual framework for classification research. From “Toward ...