![]()

1 Introduction

The soil is the common mother of all things, because she has always brought forth all things and is destined to bring them forth continuously.

Lucius Collumella, AD 60

Introduction

Columella was one of the earliest known writers on agriculture and clearly understood the importance of soil as a resource within his native Iberia (Spain). Although 71 per cent of the surface of our planet is covered by water, we still call it ‘Earth’. Along with air and water, soil is essential for life on Earth. We need soil for the growth of our crops, for grazing our animals and for the growth of our timber.

Most of the Earth’s surface is too hot, cold, wet, dry or steep for agricultural use. A surprisingly small proportion of the land surface can be used for crops. In 1987, the United Nations (UN) estimated that only 11.3 per cent of the land surface (13,077 million ha) could be used for arable and permanent crops. This resource base must support a growing world population, currently increasing by about 80 million people per year. The International Development Research Centre (IDRC), based in Ottawa, Canada, estimated the world population to be 6,159,463,956 and the area of productive land at 8,585,272,604 ha (values on 05 November 2001). The US Census placed the world population in mid-2003 at 6,302,486,693 and growing by an annual rate of 1.16 per cent. That is an extra 73,395,376 people in a year or, on average, an extra 8378 people per hour. These values are best estimates, but indicate the scale of the problem. Further information can be accessed from both the IDRC and US Census web sites, respectively at: http://www.idrc.ca/ and http://www.census.gov/ipc/www/worldpop.html (accessed 16 February 2004).

1.1 SOIL DEGRADATION

It is imperative that the soil resource base is conserved for current and future generations. An old Chinese proverb asks the pertinent question ‘once the skin is gone, where can the hair grow?’. The UN has expressed considerable concern over the status of the world’s soils. A Commission, chaired by the Norwegian Prime Minister, Gro Harlem Brundtland, investigated soil degradation and produced the Report Our Common Futurein 1987 (Brundtland, 1987). The United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) was then charged with producing a world map of the current status of world soils in a project called the ‘Global Assessment of Soil Degradation’ (GLASOD). This project was mainly coordinated by Wageningen University in The Netherlands and resulted in the publication in 1990 of the World Map of the Status of Human Induced Degradation (Oldeman et al., 1990). The GLASOD Report took a rather pessimistic view of the future, concluding ‘the earth’s soils are being washed away, rendered sterile or contaminated with toxic chemicals at a rate that cannot be sustained’.

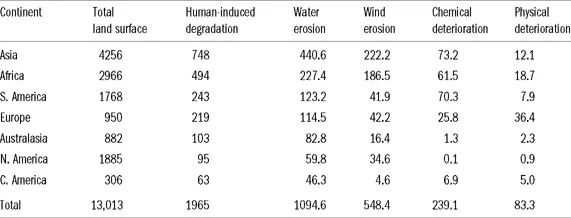

Table 1.1 Global assessment of soil degradation (millions of hectares)

Source: Oldeman et al. (1990).

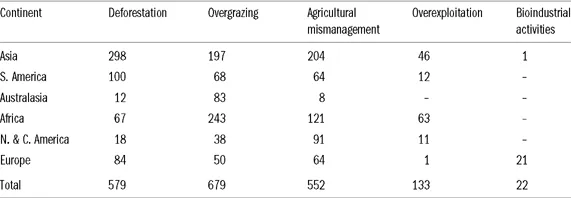

Table 1.2 Causative factors of soil degradation (millions of hectares)

Source: Oldeman et al. (1990).

GLASOD estimated that the loss of agricultural land through soil erosion was 6–7 million ha yr−1, with an additional 1.5 million ha being lost through waterlogging, salinization and alkalinization. In this context, loss does not necessarily mean the land disappears, although locally it does because of marine transgressions. Usually, it means a deterioration in soil properties to the extent that the soil is no longer productive. Table 1.1 shows the main types of soil degradation reported in the GLASOD survey and their extent on different continents. Table 1.2 breaks these down into causative factors. These data must be viewed with caution as they are ‘best estimates’. They could be challenged on several counts, including scientific rigour and accuracy, and attempts are under way to update and validate the data. However, they do clearly suggest that we have an important global problem.

Plate 1.1 The abandoned ancient city of Jiaohe, Xinjiang Province, China (photo M.A. Fullen)

History has some important lessons for us. The collapse of past civilizations resulted partly from land degradation. The fertile crescent of the Tigris–Euphrates basin (presently mainly Iraq) formed the basis of the ancient Sumerian civilization in Mesopotamia (Thomas and Middleton, 1994; Johnson and Lewis, 1995). Approximately 5000 years ago techniques for growing cereals were developed, providing the foundation of the region’s cereal-based agricultural economy. Hence, the area has been described as the ‘cradle of civilization’. Similar past civilizations included the Egyptian Empire, which developed in a corridor along the River Nile and the Han Chinese Empire, which had its focus on the Yellow River. Land degradation played a crucial role in the deterioration and eventual collapse of these civilizations.

Land degradation covers a complex series of processes, including soil erosion (by both wind and water), the expansion of desert-like conditions (desertification) and the contamination of soils with salts (salinization). It has been enmeshed in a complex series of social changes, including social unrest within and between political units and ethnic tensions. These often occurred at a time of notable climatic change. Illustrative of these changes is the ruined ancient city of Jiaohe, in Xinjiang Province, China (Plate 1.1). The city was the thriving capital community of western China. However, a combination of land degradation, mainly a result of soil erosion, desertification and salinization, increased climatic aridity, social tensions and invasions by Mongolian tribes led to the eventual abandonment of the city in the thirteenth century: http://www.travelchinaguide.com/attraction/xinjiang/turpan/jiaohe.htm (accessed 16 February 2004).

As a global community we must learn from the lessons of the past. We live in a time of climatic changes, rapid increases in the global population and rapid decreases in the extent and quality of the soil resource base. Regional military conflicts continue, especially in the world’s arid zones, and many are related to conflicts over water resources. The next nine chapters review the problems facing soil resources. They are meant not just to present a pessimistic view, but also to explore constructively ways in which we can tackle and resolve some of these issues.

1.2 SOIL SURVEY, SOIL CLASSIFICATION AND LAND EVALUATION

In order to understand and predict soil behaviour we must be able to assess soil properties, categorize and classify soils and then map their spatial distribution. In the field, soil surveyors examine a vertical ‘slice’ of soil in a pit, referred to as a soil profile. In the profile, soils are studied in layers or horizons. The nature and properties of each horizon and the relationships between horizons are considered. Some soil properties may be assessed in the field, with soil samples taken for subsequent laboratory analysis. Soil scientists who study the origin and development of soils are described as pedologists. Indeed, the term ‘ped’ frequently recurs in soil science, being taken from the Greek pedos, meaning ‘soil’.

For rapid reconnaissance and to support profile analyses, pedologists may auger soil samples or take soil cores. These narrow sections and cores are then placed on plastic sheets, for study and sampling. Sometimes topsoils are sampled for specific analyses (e.g., for soil fertility). Samples are removed from specific depths (e.g., 0–5 cm in grassland soils or 0–20 cm in cultivated soils) and samples taken for analysis.

In the field, a number of properties are assessed. Each national soil survey produces soil survey field handbooks, which in essence are similar, though with subtle differences. These provide very precise procedures for the characterization of soil properties and sampling. For instance, Hodgson (1976) described the procedures used by the Soil Survey of England and Wales (now known as the ‘National Soil Resources Institute’, NSRI). Essential properties include:

• colour (described by reference to standardized colour chips in a Munsell Colour Chart);

• texture (the relative proportions of stones, sand, silt and clay in a sample);

• structure (the arrangement of particles into aggregated units);

• consistence (the degree and kind of cohesion of soil material).

Soil samples are then transported back to the laboratory for analysis. A particularly useful introduction to field and laboratory work in soil science is provided by Marsden and Allison (1992) and an informative guide to laboratory analytical techniques is provided by Rowell (1994).

In terms of physical soil analysis, particle size analysis is the most frequently used technique. Particles are divided into selecte...