![]()

Chapter 1

Introduction

Choice and conflict are coexistent. It is our thesis that, under appropriate circumstances, there is an efficient and effective process by which an individual can arrive at an optimal choice when choosing among a variety of options. After an analysis of this mechanism and of the conditions which permit it to operate, we model the structure of conflict between individuals on it.

There is a vast literature on the subject of conflict, not because so much is known in a scientific sense but because it is so important a topic. Much of this literature is concerned with violent conflicts, particularly wars and revolutions. Neither time nor inclination permits us to review all of this literature, but, on a very selective basis, we will refer to some of the existing literature in which the ideas made use of here, or related ones, were introduced.

For our purposes a very general definition of conflict is the most appropriate: the opposition of response (behavioral) tendencies (English & English, 1958), which may be within an individual or in different individuals. Such a general definition includes conflicts such as that of an individual facing a choice between two job offers, or a conflict between the engineers and the stylists in planning a new car, or that between two sovereign states quarreling over fishing rights or one seeking hegemony over the other.

Some conflicts may not be very dramatic and are often resolved with little difficulty, but some have potential for escalation. We propose to show that there are systematic structural properties running through the spectrum of all conflicts and that these abstractions are relevant to the process of resolving conflict.

This is not a new idea. A good deal of scholarly literature has been directed at the problem of a theory of conflict. For example,

J. Bernard wrote critically in 1950 about sociological approaches to conflict. She referred to invention and change on the dynamic side, and class and caste on the structural side, as having become the fashionable explanatory and analytic tools in sociology. She felt that interactional processes had been neglected in sociological theory and so the theory of conflict had been neglected in favor of the theory of culture.

“The culture concept exonerates individuals as human beings. The culture concept emphasizes nonpersonal processes. Human beings play the role almost of puppets. Cultural analysis, as a matter of fact, could dispense with human beings entirely. Human will — free or determined n'importe — can be ignored. Even more so the conflict of human wills” (Bernard, 1950 p. 14).

Some theories and explanations are stated in terms of particular sociological structures involving the distribution of power and authority between religious groups, or minorities, or some class structure (e.g., Dahrendorf, 1958). Some explanations are “hot-blooded” — involving tension, sentiment, or frustration — or “cold-blooded” — involving strategic considerations and self-interest (e.g., Bernard, 1957; Boasson, 1958).

Substantive descriptions and contextual explanations of particular events may be insightful and satisfying, but their particularity may at the same time interfere with detecting and recognizing the more abstract features that are common to all of them. Conflicts between spouses, between management and labor, or between two sovereign states are enormously different on psychological, economic, sociological, and political levels, but on an abstract level, have, as we propose to show, a common underlying structure.

The essence of social conflict is interaction. We propose that this interaction has an abstract structure, and that concern for the peaceful resolution of social conflict may be more effectively implemented when this structure is understood in a way independent of a specific context. On an abstract structural level we will see similarities and differences of a more formal nature which are simple conceptually and valuable for adapting and transforming methods of resolution. The process of abstraction is critical for developing new methods and techniques and for the construction of general theory.

There are many different ways to organize and classify conflicts and there need be nothing incompatible or contradictory among them. Scholars with different purposes find it convenient to organize conflicts in terms most conducive to those purposes. Deutsch (1973), for example, was interested in explicating social-psychological similarities and differences among conflicts, and classified them accordingly.

For example, one classification is in terms of the relationship between the objective state of affairs and the state of affairs as perceived by the conflicting parties while another distinguishes between destructive and constructive conflicts. Anatol Rapoport (1960), in contrast, took a more formal view of conflicts and classified them into three types: fights, games, and debates. Dahrendorf (1962) offered a very complex taxonomy which Angell (1965) reduced to six types.

These distinctions are structural in the sense of referring to social structure, but they are discrete taxonomies and do not clarify the continuity or relations between types. Conflicts of different types may be more or less difficult to resolve, and the continuity can be useful in understanding the implications of transforming one type of conflict into another.

We will propose a. relatively formal logical structure into which one may map any particular conflict. The perspective taken in this analysis of the structure of conflict is what Schellenberg (1982) refers to as a social psychological one, a conflict of interest between individuals, motivated by self-interest and bounded by moral and ethical limits. This is an approach he identifies with Adam Smith's Wealth of Nations (1776) and is distinguished from a biological perspective and a sociological perspective; it is also distinguished from “hot-blooded” explanations of the origins of conflict.

The structure developed here provides a classification into types that are relevant to the selection of appropriate methods of conflict resolution. The interrelations of these types control the transfer and adaptability of methods of conflict resolution from one to another.

We are not primarily concerned here with the sequential programming of the interactions of the parties involved in the course of seeking to resolve a conflict. A very considerable literature already exists with this aspect as its main concern. Some of it is in a popular vein and some of it is serious scholarship (see, for example, Calero, 1979; Douglas, 1957; Oliva, Peters, & Murthy, 1981; Raiffa, 1982; and Schelling, 1960). Most of these provide descriptions of the bargaining or negotiation process and how to be effective at it. In Chapters 9 and 13 we will discuss the relation of some of this work, particularly game theory, to the structure developed here.

This monograph is directed at understanding conditions that ensure the selection of an optimal resolution and how these conditions might be approximated in the most complex conflict situations. Negotiation is perhaps the most familiar procedure for resolving conflict, but it is not equally successful in all conflicts. Other procedures are available, are used, and may be more or less effective. We are interested in the properties of conflict which make different procedures

effective. We seek to characterize the varieties of conflict in ways most useful in the selection of a procedure for resolving particular conflicts and in identifying some of the problem areas most amenable to empirical study.

In the course of developing the structural relations that characterize and distinguish conflicts, some old and familiar concepts and problems arise which sometimes require elaboration, redefinition, and new interpretations. We will see that a given conflict may seem to be of one type, yet from another perspective appear to be of another type. Different categorizations may sometimes be a matter of framing, which is just as important in its effect on conflict between individuals as Tversky and Kahneman (1981) have shown it to be in individual decision making. We shall discuss the advantages and disadvantages of the transformation of a conflict from one type to another. We will see that something is gained and something is lost because such transformations involve a tradeoff between ease of finding a resolution and the power necessary to impose it.

As a first step we will distinguish between three types of conflict; the first is conflict within an individual, and the other two are types of social conflict. For lack of adequate descriptive terms we will simply call them Types I, II, and III.

Briefly, the three types of conflict are characterized as follows. Type I is conflict within an individual because he or she is torn between incompatible goals. An example is the individual faced with a choice between two vacation intervals, where one has more pleasurable activities available and the other is less expensive. Or consider a student choosing between two majors, one of which is less interesting but offers better job prospects. In each case the individual is pulled in conflicting directions by goals that are incompatible because no option exists which satisfies both goals maximally.

Types II and III are conflicts between individuals. Type II is conflict between individuals because they want different things and must settle for the same thing. An example would be a conflict between husband and wife who disagree on whether to buy a new house or a new car; or disagreement between labor and management on a wage scale; or two superpowers in disagreement over arms control. In each case a decision is sought that both parties will accept.

Type III is conflict between individuals because they want the same thing and must settle for different things. An example would be that of two men courting the same woman or two governments who want the same island. Only one, at most, can achieve the goal; the other party must settle for something different.

We shall use the Type I conflict as a paradigm because there is

some substantial theory about the optimal resolution of such a conflict. We will expand on that theory and examine the more complex problems of social conflict, Types II and III, in that framework.

![]()

Part I

Type I Conflict

conflict that arises within individuals because they are torn between incompatible goals

![]()

Chapter 2

The Theory of Individual Preference: Type I Conflict Resolution

2.1 Introduction

The conflict between incompatible goals felt by an individual who must make a difficult choice is usually regarded as something quite distinct from conflict between individuals, and it may seem unreasonable to expect such intraindividual conflict to serve as a model for understanding interindividual conflict. We will show, however, that a theory of individual preference that describes conditions under which an optimal decision is most easily reached has important applications to conflicts between individuals. Most of this book is devoted to exploring these applications.

Our purpose in this chapter is to introduce some ideas from the theory of individual preferential choice that underlie most of our subsequent development of the structure of conflict. These ideas are concerned with the very special situation in which the individual is choosing a single option from an ordered set and preference is described by a “single peaked” function.

Our interest in individual preference theory is restricted to such a special case because this case is all that is needed for modeling certain conflicts between individuals. The reason that this case is sufficient is not that the options and preferences in such conflicts between individuals are simple — on the contrary, they are at least as complex as those involved in individual choice. Rather, it is sufficient because the options in a conflict between two parties may be screened to reduce them to an ordered set. Furthermore, this ordered set consists of the best options available, in the sense that any other choice would involve unnecessary concession by one or both of the parties, and the preference of each party is single peaked over this set.

This book is intended not just for academicians but also for experienced practitioners of conflict resolution whose formal mathematical training may be slight or far in the past. Our focus is on the ideas behind the formal theory and technical foundations. Detailed mathematical treatment is set apart in technical notes and the appendices and is not necessary for a working understanding of the structure we propose. This part of our discussion is, however, necessarily somewhat general and abstract. Our hope is that the generality will make previously unnoticed relationships visible and lead to increasing effectiveness in practice.

2.2 Single Peaked Functions

With simple stimuli as options — like the amount of sugar in coffee or the temperature of a shower — an individual's preference may often be described by a single peaked function (SPF) (J. Priestley, 1775; Wundt, 1874). That is, when simple options have a natural underlying ordering, preference generally increases up to some point in the ordering and then decreases. If the options are more complex, as in choosing a college or where to go for a vacation, preference is less often described by a single peaked function. This is true even when there is a natural ordering of the options based on some aspect such as cost. In general, preference functions over the ordering of these complex options may have several peaks with valleys between them.

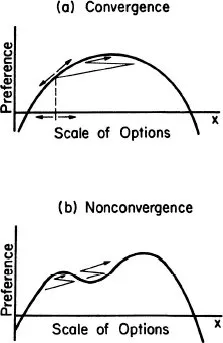

The significance of SPFs is that they allow a simple search process that converges on the optimal decision. (The term “optimal” in this context means what is best for the individual from that individual's point of view.)

This search is illustrated in Figure 1(a) with an SPF over a scale of options, x. Starting at any point, moving in one direction decreases preference and moving in the other direction increases preference, except at the optimal point where a change in any direction decreases preference. With a preference function having several peaks, as illustrated in Figure 1(b), the search process can be trapped at a local maximum or be divergent. An exhaustive search is the only way to ensure that the optimal choice is found in such a situation, and such a search may be stressful, more costly than it's worth, or even impossible.

Figure 1: Search for optimality

A homely example of such a search process is that of adjusting the temperature of a shower. If turning a handle one way increases the temperature of the water and turning it the other way decreases it, finding a particular temperature is a simple procedure. But if turning th...