1 Development and Under-Development

In this second half of the twentieth century we have become particularly aware that the world is experiencing a population problem that steadily grows more acute, and also of a growing problem of world poverty. It is not surprising that a broad correlation between these two conditions is readily assumed by large numbers of people, who tend to regard the one as being the prime cause of the other. In fact, this is by no means true, although the demographic factor plays a powerful part in affecting the levels of national wealth and the speed of accumulation of wealth by nations. Much of the poverty of a large part of the world is due to under-development of resources. The United Nations General Assembly has recognised this in designating the 1960s as the ‘United Nations Development Decade’. In a sense the term ‘under-developed’ is a euphemism for ‘poor’.

The rich nations of the world are remarkably few in number. They lie in the temperate zone and are populated mainly by European stock. They include the United States and Canada, the United Kingdom and the countries of Western Europe, Australia and New Zealand. The top twelve richest nations include only one-tenth of the world’s population. The USSR, Japan, Argentina and Venezuela might be regarded as well off, and together with the top twelve account for about one-fifth of the world’s peoples: four-fifths live in varying degrees of poverty. The poor countries lie mainly in South and Eastern Europe, in Asia, Africa and Latin America, and their economies are regarded as under-developed in comparison with the few rich lands whose economies reveal a wider diversity of activities embodying the fruits of science and technology and heavy investment of capital.

Under-developed countries are characterised by a high degree of subsistence production with a very limited application of technology; as a consequence manufacturing industry is relatively unimportant and the agricultural sector is paramount. This book is concerned with the development of the industrial sector of such economies as a part of the process of economic development, but it must be understood that industrialization is not a general panacea for all the poor countries of the world. The problem is not simply that their economies lack a substantial industrial sector, but that in many cases even their agricultural sectors are highly inefficient and generally social and institutional patterns make advance in any field extremely difficult. Economic development is not synonymous with industrialization alone, but applies to all sectors of an economy and implies a relative change in their order of importance with the application of science and technology, raising productivity per worker and releasing labour and resources for yet other productive tasks. All sectors (agriculture, mining, manufacturing industry, commerce, services) should advance. Industry, therefore, is but one part of an economy, albeit a very important one, and there is a close inter-relationship between all the parts. It is also implicit in the general argument that there is no ceiling to the degree of development possible and that this applies just as much to under-developed countries as to their rich neighbours. Canada, for all its present wealth and degree of development, has vast resources still under-utilised and in this way resembles Brazil and a host of other under-developed lands. Clearly, then, the epithet of ‘developed’ or ‘under-developed’ is not based upon potential but rather upon existing levels of wealth and material welfare, but the term ‘under-developed’ has a dynamic implication in that it suggests that there is a margin of resources (human and material) that can be developed.

It is not easy to assess and compare the economic welfare of a diversity of nations, particularly when the poorer ones from their very poverty have not the precise knowledge, let alone statistics, of their own conditions. Moreover, it would be hard to get agreement among different peoples as to the meaning of economic well-being: the cultural wants of a highly developed people might seem incomprehensible to the primitive wants for food, clothing and shelter of the world’s poorer peoples. On the other hand, some countries generally accepted as under-developed have cultures and civilisations going far back to the time when temperate Western Europe and North America comprised inhospitable forests and bogs. From this it would seem that ‘under-developed’ is a broad term encompassing states with a wide diversity of attributes and that strictly it should be used to reflect a low standard of technical and economic attainment only.

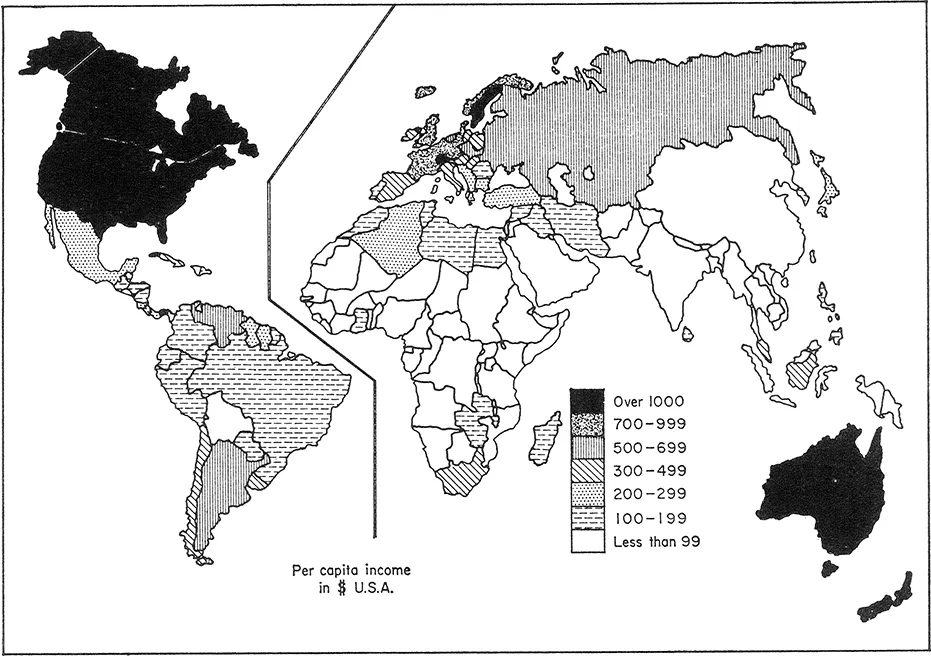

Fig. 1. World per capita net incomes 1956–8

The customary common denominator allowing a measure of comparison between countries is that of per capita income, obtained by dividing the estimated total net national income by the total population. The limitations of such a yardstick are apparent if the method of calculation is examined. The net national income is taken to be the sum of all goods and services produced during a year after deduction for fuel, raw materials and all other costs of production including depreciation. Wages, salaries, profits, interest and rent are all included: they are certainly applicable in developed countries but are rather unrealistic for the mass of peasantry in the poorer lands. The difficulty of giving monetary value to peasant production in a subsistence economy is clear, particularly when it is remembered that such peoples perform many services for themselves and neighbours (domestic help, cooking, washing, etc.) which are paid employments in developed countries and appear with some precision in the one reckoning but scarcely at all (or at best as ‘guesstimates’) in the other. It is likely that subsistence economies are under-valued; also, not only is it difficult to equate local values with world values, but conditions of living have to be taken into account. Minimum requirements of food and clothing are less in hot countries than in areas nearer the Poles and it usually costs less to live in the village than it does in the town, both of which comparisons serve to underline the approximate character of any estimates of net national income and discounts the degree of precision that the use of such figures might imply. To this problem may be coupled the frequent lack of knowledge of the size and composition of the working population.

Incomes per head are not the sole indices available; one other that has received some acceptance is a measure of the available energy per head of population. Historically, development has been characterised by a growing replacement of animate by inanimate energy. A country with plenty of power behind the elbows of its workers is one that lives well: productivity in all sections of the economy is high. This productivity may be evaluated in units of currency but it is also measurable in units of energy, for it is generally accepted that a close relationship exists between levels of energy consumption and levels of economic activity (see table 8, p. 114).1 Income per head, being expressed in monetary terms, is the more widely accepted, although besides the element of unreliability a number of anomalies are patent. For example, the oil-rich sheikdom of Kuwait records a per capita net income twice as high as that of Britain, but it would be ridiculous even to attempt a comparison of the economies of the two countries or the standards of living of the masses of the people in them.

With the help of the table of per capita incomes (table 1) a map (fig. 1) has been constructed to show the world distribution of incomes and therefore in broad terms to reveal the rich and poor, the developed and under-developed nations. An examination of the table and map reveals that the world’s wealth is extremely unevenly distributed, that the range between the richest and the poorest nations is surprisingly wide and that on the whole the world is still a very much under-developed planet. The inequality of income between various countries is most striking. A United States citizen nominally commands about twice the per capita income of each of us in the United Kingdom, while our average income per head is ten to fifteen times that of the world’s poorest countries. The correlation between highest incomes and the temperate climatic zones is another striking feature and may well reflect climatic influences upon man’s mental and physical productivity, a field of study in which much work remains to be done.

Fryer has attempted a classification and analysis of levels of economic development throughout the world. He makes a fourfold division of types of economies: highly developed, semi-developed, under-developed and planned (Communist) economies. The highly developed economy is primarily industrial-commercial, the semi-developed economy is mixed industrial-agricultural. These two groups support about 20 per cent of world population. Underdeveloped economies are primarily agricultural and may account for 50 per cent of world population, while planned economies exhibit some features from each of the other three groups,2 This is a useful general classification, but with respect to the under-developed lands needs to be probed further.

Differences in under-developed countries

The use of the broad term ‘under-developed’ must not blind us to the great differences between the under-developed countries themselves. Since they comprise the greater part of the world this is hardly surprising, but it is worth drawing attention to these differences to emphasise that there is no omnibus solution to the problems of under-developed lands, that the final answer for each country is an individual one. Numerous generalisations are frequently made about the under-developed countries, implying homogeneity rather than heterogeneity. There are some affinities and common characteristics, to be sure, but too often generalisations based upon them mask wide diversities.

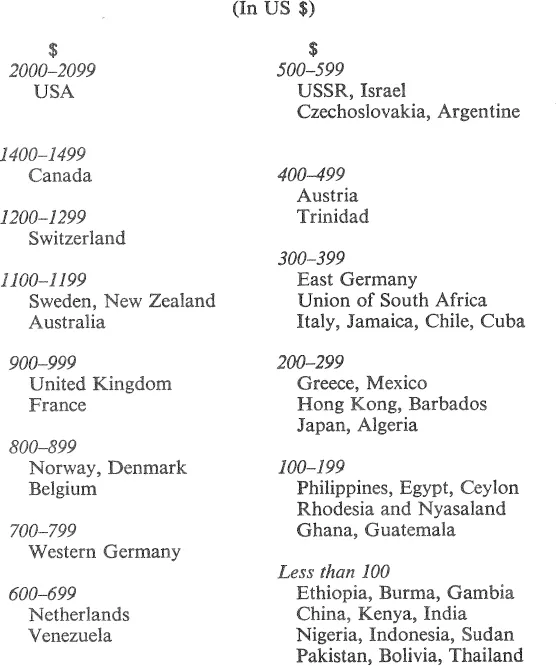

Table 1 Per Capita Net Incomes of Selected Countries (1956–8)

By definition one characteristic of the under-developed countries is that they are poor, both in income and capital, but there is a considerable range in degrees of poverty. The average net income per head in Burma is less than £20 per annum, in the Philippines £50–60, in Greece £75, Chile £120, and so on. At the bottom, poverty is utter and absolute but up the scale it becomes relative and more tolerable. Further, when we examine the conditions of individual countries marked differences are apparent in the distribution of the national income. The per capita figures are averages assuming each man as rich as his neighbour, but this is unreal—even in Communist countries—and in many under-developed countries (e.g. the Middle East oil producers) the bulk of the country’s wealth is in the hands of a small minority, the mass of the people exist at a standard far lower than the per capita income implies. Under-developed countries also differ in their rates of economic growth, some have been making advances while others remain static or even recede.

If we now turn to the population factor it is evident that very important differences materially affecting economies and rates of growth lie in the varying degrees of under- or over-population, the structures of the populations and their rates of increase. Some countries, such as India and Egypt, are heavily over-populated, others, such as Brazil and Ghana, are under-populated; both conditions retard economic development. These demographic features are considered in greater detail later, but here it must be stressed that over-population is but one contributive cause of under-development and national poverty and that only a few countries in the world so far are seriously affected by it. However, the ‘population explosions’ of the last two decades are especially marked in many under-developed countries, particularly of South-east Asia and Latin America, and their present impoverished economies relying mainly on relatively backward agriculture are unlikely to expand at a rate comparable with the rapid population increase so that low living standards may fall even more.

A further characteristic of under-developed countries is the substantial part agriculture plays in their way of life. Again wide differences exist, ranging from almost complete dependence upon subsistence agriculture to dependence upon agricultural exports and the imports of some foodstuffs. A capitalisation of favourable climate and soil linked with organisation and experience has led to specialist commercial production, such as tea in Ceylon, cocoa in Ghana, coffee in Brazil, sugar in Cuba, rubber in Malaya; much of this agriculture is highly efficient. Land tenure systems also vary considerably, being tribal or communal in some areas and with individual freeholds in others. In some countries ranked as under-developed, large-scale irrigation works make natural desert areas habitable and cultivable, in other similarly ranked countries shifting cultivation still pertains. Some under-developed countries export minerals, oil being the most outstanding example, but also, e.g. copper from Zambia and from Chile, tin from Malaya, iron ore and phosphates from Algeria. It is true to say that the majority of under-developed countries participate to varying degrees in international trade, exporting usually only one or two primary products, and one of their problems is vulnerability to any fall in world prices.

It will be clear from the foregoing exposition that the under-developed countries are at widely different stages of advancement. Some, judged by their institutional arrangements, the aptitudes and education of the population and their commercial standing, are ripe for the financial, social and economic changes that development brings; others may be less ready. The readiness of investors, both internal and external, to deploy their capital in a country indicates some measure of its potentiality for advance from a traditional economy to a diversified and complex economic structure and to a position where enough capital is engendered for reinvestment to sustain progress and economic growth.

Some reasons for under-development

There are many reasons contributing to under-development. By our present-day standards all countries were once in that condition (although they would not have considered themselves so at the time); what has happened is that over the centuries a few by energy, invention and determination have paced farther and farther ahead of the majority who have moved but slowly, while some have scarcely moved at all. A disturbing feature for the newly awakened world conscience is that the pace of progress of the few leading countries is accelerating rapidly, the progression seems to be geometric—the rich become richer and the poor relatively (and in a few cases, absolutely) poorer. During the years 1952–6 when India had launched her first Five Year Plan her income per head rose by barely £1, whereas Britain’s income per head rose by nearly £40. The large rolling snowball picks up much more snow than the tiny one just beginning to roll This multiplier element, more and more evident as development gets under way, is an integral factor to be invoked in economic plans for development. Cumulative growth, even at apparently slow rates over the years, can, however, have astonishing results. At the beginning of the twentieth century the United Kingdom and the United States enjoyed approximately identical levels of real income per head, but since then American rate of progress has averaged about 2 per cent and the British about 1 per cent per annum. Sixty years’ growth at these speeds and allowing for compound interest now gives the United States rather more than double the British average income per head. The differing rates of growth seem small, but the result over a period of time is of great consequence.

Geographers are interested in, and can make useful contributions to, problems of development. A particular field the geographer tends to regard as his own and to evaluate highly in importance is that of resource endowment. There is a danger that the role and significance of possession or non-possession of natural resources in economic development may be misunderstood. Development and under-development is often loosely attributed to the maldistribution of natural resources or to particular geographical disadvantages of certain countries, such as their world position, size, character of the relief, soils and climate. These views are somewhat erroneous; certainly, the possession of varied natural resources can be advantageous but in themselves resources are not decisive. It is not difficult for the geographer to name well-endowed countries that are still backward in development and to indicate other countries, highly advanced yet apparently possessing few natural resources. Brazil and Indonesia, Switzerland and Denmark provide two examples of each. Brazil, despite only limited geological survey, is known to have a plenitude of mineral resources, its large size and varied structure offer a diversity of topography, climates, soils and mineral wealth, yet it remains undeveloped and the per capita income of about £30 is among the world’s lowest. On the other hand, Denmark, despite a lack of minerals and energy resources, a small size, a homogeneity of relief and climate, has developed her economy to such an extent that on a per capita income basis she is one of the richest countries in Europe.

These examples also serve to disprove the contention that size of country is a major factor in development. We can see countries of equal size enjoying a very different standard of living and large countries seem to have no advantage over small ones and vice versa. The multitude of factors bearing upon the well-being of different countries make it very difficult to isolate and evaluate the significance of size in this connection. It is true that great areas may connote a rich and diversified endowment of natural resources, but this merely gives a potentiality. Far more depends upon man’s numbers, energy, knowledge, and sense of purpose. Capital can substitute for natural resources as we see in the case of Swizerland where, however, among other geographical factors, position plays an important part.

These examples suggest that much more than possession of resources is necessary for the furtherance of economic development; not even the economist’s triumvirate, land (Le. resources), labour and capital, are by any means the sole determinants of economic progress. Perhaps the most important factors are human ones: in the last resort everything depends upon the peo...