![]()

Part I

An Art-Based View of Child Development

![]()

1 The Pictorial Language of Child Development

Theoretical Underpinnings

Would any book of this nature be complete without reference to the saying “One picture is worth a thousand words”? Due to the fact that pictures are the primary language of child art therapy, these words are especially apt. Comprehension of the pictorial language of child development is an essential tool for effective child art therapy practice. This becomes the basis for understanding and engaging the wide variety of individual clients. For art therapists treating children, fluency in the language of art is a professional tool that is developed through personal art experiences and through the study of children’s artwork. Such knowledge allows access to the inner world of children. It enables an understanding of emotional, interpersonal, and cognitive experiences at each stage of childhood. This fluency allows the art therapist access to the strengths, struggles, and motivations of child clients; it provides a compass for navigating the varied terrain of children’s experiences, environments, and cultures. The art therapist’s understanding of developmental stages, as related to the pictorial language of children, assists in developing understanding of the complexities of each child during the assessment and treatment processes.

In keeping with the focus on childhood of the book as a whole, this chapter explores the stages of visual art by children up to 12. Developmental theories and children’s art are compared to revisit what it is like to be a child, progressing through age-related stages. This experience becomes the basis for entry into the creative and visual inner world of preadolescent children.

Artwork tells the story of a child’s development and reflects each child’s unique vision. This is one reason why child art is fascinating and delightful. Art expression reveals individual characteristics as well as aspects of child development that are universal. There are developmental sequences that all children go through, such as learning to walk or speak. Creativity and artistic expression also involve predictable developmental stages. It is the job of the art therapist treating children to study both the universal and the personal elements of development as a means of understanding creative expression and its relationship to functioning. An understanding of the interaction of creative and biological development can reveal various options for how to help children who experience disturbances as well as those who struggle with the challenges inherent in normal development.

Child Art Expression: A Snapshot of Child Development

Child artwork speaks eloquently about the child’s perceptions, emotions, thoughts, and physical experiences. The nature of art is that it conveys something deeply meaningful about both individual and universal experiences. The viewer of artwork is invited to understand and empathize with the artist and to comprehend more broadly what it is to be human. Art expression has the potential to be satisfying and significant for both the artist and the audience.

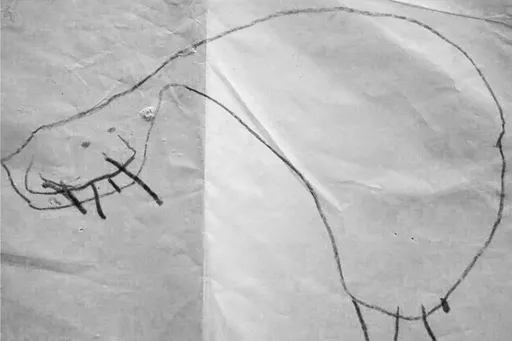

It is difficult for most adults to remember what it felt like to be a small child. One way to be reminded is to look at art by young children. In doing so, one may remember the sense of playfulness and the joy of making silly pictures. For example, Figure 1.1 shows a drawing of an imaginary dinosaur by a 5-year-old boy. It reflects a time of intense curiosity and imagination that occurs prior to learning to read, write, and perform competitively. The large playful dinosaur is the center of attention in the scene, reflecting the imaginative innocence and egocentric qualities of a preschool child. The relative lack of fine motor control leads to a slightly clumsy but uninhibited and frolicking quality, unique to children at this stage of life. The capacity to freely imagine and to mix elements of fantasy and reality also speaks about the experience of the preschool child who is not yet firmly situated in reality. Through experiences, maturational processes, and the help of parents, the child develops an increasing capacity to become reality oriented. While playfulness is a universal experience for young children, in content and quality it always reflects the varied values, norms, and relational patterns derived from parents and the community at large (Golomb, 2011).

Figure 1.1 Dinosaur by 5-year-old-boy

Figure 1.2 is a self-portrait by a 3-year-old girl. As in the previous example, the drawing reflects the bold simplicity inherent in the aesthetic and perceptual experience that is a feature of what Erik Erikson (1950) referred to as the play age. At this stage of development, children rarely depict groupings of people but usually portray isolated figures. This is generally not an expression of loneliness or isolation but is more likely attributable to a healthy level of egocentricity. This type of human figure, which includes a large head and no torso, is referred to as a “tadpole” figure (Golomb, 2003). (See chapter 2 for further discussion of the play age.)

Figure 1.2 Self-portrait by 3-year-old girl

During the elementary school years, however, children often depict groupings of people. Cooperative and competitive teamwork is a way of life for children by second or third grade, and their art reflects this. This is not to say that older children no longer depict large solitary figures, but in general, their experience and perceptions encompass more complex relationships as they mature interpersonally. Figure 1.3, a family portrait by an 8-year-old girl, illustrates many features of middle childhood: increased sense of reality; good fine-motor control; clear gender identity; awareness of one’s role within a family, community, or peer group; and a high level of attention to detail. Also evident is the considerable presence of impulse control and frustration tolerance, which would be abnormal in a preschooler. While the characteristics of early art expression tend to be universal, western culture influences children to depict increasingly realistic representations as they mature. In many nonindustrialized cultures, artistic representation is characterized by symbolism and decoration (Golomb, 2011).

Figure 1.3 Family drawing by 8-year-old girl

The above examples illustrate how the language of art encapsulates the fundamentals of child development. Rapid developmental gains are apparent in these drawings, which span just a few years. The first two illustrations reveal much about the playful innocence of the preschool years, while the third example illustrates the sense of order and conformity that develops gradually during the subsequent school years. Because art expression reveals much about individual and universal experiences, it provides not only the basis for understanding and empathizing with the individual child, but also the basis for understanding experiences of children in general. The study of child art expression provides a means for conceptualizing normal development as well as for detecting abnormal development. In other words, the art therapist is as concerned with signs of normality evident in artwork as with signs of failed maturation.

Importance of Developmental Theories

Developmental theories are based on rigorous and systematic observation of samples of people. They allow practitioners to be aware of generalities about how human beings function at various stages throughout the life cycle. Integration of developmental theories should be incorporated into practice, providing some objective measures for understanding both general and unique qualities of children. Clinical practice that is built upon developmental theory reduces the possibility of basing assessment and treatment exclusively on intuition or emotional reactions. This is not to say that art therapists should avoid using their intuition and emotional reactions as additional tools. Emotional reactions to art and interpersonal relationships are also key factors in conducting child art therapy. If emotional reactions were not part of the art therapist’s tools, therapeutic relationships and processes would be meaningless. At the same time, knowledge of recent research and theory provides important objectivity that protects against mistaking supposition for fact.

There have been systematic studies of child development in a range of areas including physical, cognitive, psychosocial, psychosexual, and moral development. Developmental theories overlap, describing similar experiences from different angles. Likewise, children’s art expressions provide snapshots of developmental stages, encompassing multiple aspects of development. Such snapshots provide eloquent material for a deep understanding of the sequences of child development. Winnicott (1971b) stated that a child therapist should have “in one’s bones a theory of emotional development of the child” (p. 3). Studying children’s art is a good way to enrich one’s “bones.” Art expression synthesizes so many areas of functioning that if one understands the language of art from a developmental perspective, it becomes a shortcut to understanding both child development and the essence of what it is like to be a child. This is a basis not only for sound clinical work but also for developing empathy, a crucial component of the treatment process.

The more one studies and observes, the more it becomes clear that art expression, speech, behavior, and perception are all very similar in their progression (Lindstrom, 1970). For example, children’s speech begins with random sounds and eventually progresses to words, then sentences. Children’s artwork has a similar evolution. It moves along a path that begins with manipulation of mashed bananas in the high chair, to making random scribbles, marks, and shapes on paper; to organization of forms; and eventually, to an organized and detailed visual narrative. In all areas of functioning, the increasingly complex grasp of reality is gradually developed through the child’s own unique perspective, culminating in such functions as logic, abstract thought, ability to comprehend contradictory points of view, and ability to artistically portray perspective and gradation.

Expression of Destructive Feelings and Developmental Stages

Potentially destructive feelings, such as anger and envy, are part of the normal human experience. Preschoolers and older children with disturbances often demonstrate impaired ability to modulate such feelings. Because anger and destructive fantasies are normal, it is not unusual for artwork done by children who experience normal and pathological development to look somewhat similar. The degree and quality of such expression, as well as the age of the child, are factors to consider in evaluating the level of each child’s adjustment.

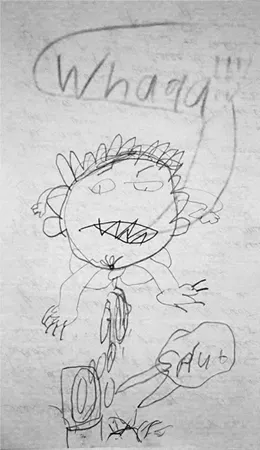

For example, a 6-year-old boy, who had just spent some time in the presence of a baby, completed the drawing in Figure 1.4. He attempted to depict his perception of the helpless, incontinent state of this infant, perhaps as a way to reinforce to his own mastery of bodily functions and to reconcile both envy and repulsion in response to the baby’s extreme level of dependency and helplessness. Several reactions including humor, fascination, and repulsion are included in this child’s artistic portrayal, which exaggerates the baby’s lack of body control and seemingly disgusting tendencies. It is normal for young children to react to a baby with envy and repulsion, a means of regression that solidifies their own developmental accomplishments.

Figure 1.4 Baby by 6-year-old boy

Six-year-old children have not fully mastered the ability to control impulses. They still cause accidental messes and experience lapses in impulse or bodily control. Consequently, their art may include themes or an artistic style that reflects loss of control along with the intent to regain control. At one moment 6-year-olds can seem very grownup, and at the next, the composure falls apart; the child is reduced to tears or lashes out.

It is interesting to compare Figure 1.5, an impulsively executed drawing by a troubled preadolescent, to the 6-year-old boy’s depiction of a b...