- 264 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Considering the interrelationships between disability and housing design with a focus on the role of policy in addressing the housing needs of disabled people, this book sets out some of the broader debates about the nature of housing, quality and design. In what ways are domestic design and architecture implicated in inhibiting or facilitating mobility and movement of people? What is the nature of government regulation and policy in relation to the design of home environments? The author addresses these questions, and brings a range of approaches to accessible design in housing to the forefront of debate, assessing how far policies and practices are equal to the challenge of creating accessible and desirable home environments.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Accessible Housing by Rob Imrie in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Architecture General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

ArchitectureSubtopic

Architecture GeneralPart I

Concepts and Contexts

1 Accessible housing, quality and design

1.1 Introduction

Disabled people’s consumption of housing continues to be hindered by poor design that inhibits their access into, and ease of mobility around, dwellings. For instance, Mrs B., a client of the British charity Age Concern, recounted a familiar, everyday, tale: ‘poorly designed housing doesn’t merely limit my independence, it makes it impossible … I use a wheelchair all the time and cannot manage a step’ (Age Concern, 1995: 1).1 Rookard (1995: 1) recalled a similar situation with her father’s difficulties in using a wheelchair: ‘we are unable to visit my nephew and his wife in their new home due to the layout of their entrance area … Are disabled people supposed to sit in their own home all day?’ Likewise, Edward Bannister (2003), a disability advocate who lives in Bolingbrook near Chicago, identified the limitations of design in relation to catering for his mobility impairment: ‘me and my family were living in a town house, my bedroom was on the second floor and it got to the point where I couldn’t get up and down to my bedroom’.2

Such sentiments are commonplace, and highlight the limitations of the design of domestic environments in relation to the needs of disabled people. Most dwellings are designed and constructed as ‘types’ that comprise standard fixtures and fittings that are not sensitive to variations in bodily form, capabilities and needs (Imrie and Hall, 2001b; Imrie, 2003c; Milner and Madigan, 2004). Builders, building professionals and others assume that (disabled) people will be able to adjust to the (pre-fixed) design of domestic space (see the discussion in Chapter 2). Such attitudes are endemic to the house-building industry in the UK, the USA and elsewhere, and are symptomatic of a disabling, and disablist, society that fails to recognize or understand that disabled people’s abilities to adjust or adapt to design are likely to be conditioned by the nature of the design itself (and the underlying values and practices that shape it).

In developing such arguments, the next part of the chapter briefly outlines the broader patterns and process that characterize disabled people’s housing circumstances. As the Introduction to the book intimates, disabled people have rarely had access to good-quality housing, or had the means to exercise meaningful choice in housing markets. More often than not, disabled people are confined to dwellings provided by a local authority or a social housing provider or, alternatively, reside in an institutional setting (Barnes, 1991; Ravatz, 1995). In particular, disabled people’s pre-1948 experiences of domestic environments revolved primarily around either dependence on care in the family home, or the application of a mixture of punitive and charitable actions by a range of state and voluntary organizations. I suggest that these and related dwelling circumstances serve to potentially (re)produce undignified domestic circumstances for disabled people, and can be conceived of as perpetuating what Dikec (2001) refers to as spatial injustice.

I then turn to a discussion of the concept of housing quality and its relevance to the dwelling needs of disabled people. Housing quality is, as Lawrence (1995) suggests, a multifaceted and complex term that ought to encompass not only a consideration of the architectural and technical aspects of dwellings, but also the broader social and political contexts that shape their provision and availability. However, for Lawrence (1995) and others, policy-makers and built environment professionals more generally tend to emphasize the former at the expense of the latter, thus conceiving of the dwelling as a piece of hardware – that is, a physical or technical system operating more or less independently of socio-economic contexts or conditions (Goodchild and Furbey, 1986; Karn and Sheridan, 1994; Goodchild, 1997; Carmona, 2001; Franklin, 2001; Imrie, 2003a). Building codes and regulations relating to access reflect this concept of housing quality and, as I shall argue, this can potentially lead to a one-dimensional approach to and understanding of disabled people’s dwelling needs.

This approach emphasizes that housing quality can be achieved first and foremost by recourse to the application of physical design or technical solutions, such as the standards relating to or derived from Part M (1999), life-time homes (LTH), smart homes and/or flexible or demountable fixtures and fittings. However, while the application of such standards is necessary in attaining particular aspects of housing quality (i.e. physical design standards), I will develop the argument, outlined by Franklin (2001: 83), that the ‘mechanistic and deterministic formulations’ underpinning them will fail, in and of themselves, to produce the quality of livable spaces responsive to the differentiated and complex needs of people (see also Turner, 1976). As Arias (1993: xvi) suggests, too many resources have been ‘wasted on engineering and architectural solutions that do not answer the human concerns that turn houses into a home’.

In this respect, the penultimate part of the chapter will explore the possibilities of developing and applying a concept of housing quality that revolves around what Goodchild (1997) refers to as the house as a home or a place of personalization. For Goodchild (1997) and others, the quality of dwelling resides in its use, and this, for Arias (1993), is closely related to personal taste and human practice. As Arias (1993) suggests, housing quality, as a lived and tangible reality, must be related to and given content by the affective desires and emotions of dwellers. I relate such ideas to broader concerns, raised by Turner (1976), Habraken (1972) and others, that housing quality must involve a decentralization of control over the processes of planning, design and production of dwellings, part of what King (1996) refers to as a vernacular housing process (see also Rowe, 1993; Hill, 2003).

1.2 Indignity, Disability and Housing

For some commentators, disabled people’s housing circumstances have rarely been dignified (Barnes, 1991; Harrison and Davis, 2001; Heywood et al., 2002). Until the passing of the National Assistance Act (1948) in the UK, disabled people either lived with a family member or, if the family was unable to support them, in a private asylum or a workhouse (see Figure 1.1; Rostron, 1995). After 1948, while local authorities were empowered to provide specialist accommodation for disabled people, less than 50 per cent had done so by the 1980s.3 Most provision, outside of the family setting, was by voluntary sector organizations, such as the Leonard Cheshire Homes and The Thistle Foundation. These were, and still are, regarded by many disabled people as perpetuating paternalistic and undignified forms of housing consumption (Hannaford, 1985; Morris, 1991). Hannaford (1985: 61) refers to such places as where disabled people were blamed for their circumstances: ‘disability tends to be seen within social work analysis; it becomes a social problem’.

1.1 Institutional living.

Since the early 1950s, British local authorities have been encouraged to provide for disabled people’s housing needs through a mixture of, primarily, non-statutory policy programmes (see Borsay, 1986). These have ranged from the adaptation of existing housing, such as the removal of front doorsteps and their replacement with ramped access and accessible thresholds, to the construction of homes designed to cater for wheelchair users and people with mobility or ambulant impairments. Until 1970, and the passing of the Chronically Sick and Disabled Persons Act (CSDP) (Department of Health, 1970), few purpose-built houses were constructed and most local authorities did little to respond to the housing needs of disabled people. Thereafter, the CSDP made it a statutory duty for local authorities to have regard ‘to the special needs of chronically sick and disabled persons’ when devising local housing policy (Department of Health, 1970: 3). In combination with related legislation, such as the 1974 Housing Act and the Local Government and Housing Act of 1989, the CSDP provided a framework for, potentially, changing the housing circumstances of disabled people.4

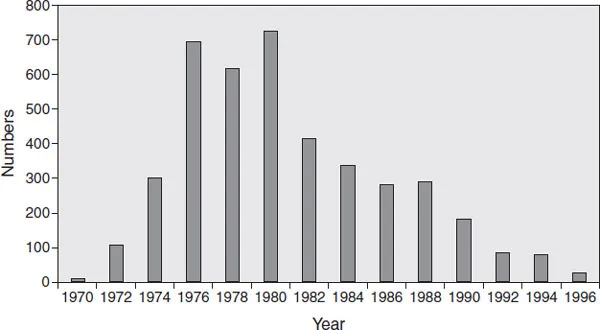

However, assessments of the CSDP, and related legislation, note that the legal provisions were beset by problems of vagueness and ambiguity, and were rarely used to their full potential by local authorities (Armitage, 1983; Borsay, 1986).5 For instance, Laune’s (1990) review of housing and independent living for disabled people documents the decline in provision of wheelchair and mobility dwellings in the 1980s. In 1979, housing associations in England constructed 129 new wheelchair-standard properties, in contrast with 571 constructed by local authorities (see Figure 1.2). By 1995 these figures had fallen, respectively, to 67 and 69 dwellings. Over the same period, the numbers of new mobility-standard properties declined from 2,136 (housing associations) and 5,950 (local authorities) to 102 and 469 respectively.6 Such figures were at odds with the Conservative government’s statement in 1989 that ‘it remains the government’s policy to provide the building of accessible housing and this is an area where housing associations and housing authorities have taken a lead’ (Department of Health, 1989: 4).

1.2 Completion of wheelchair dwellings in England by local authorities, 1970–96. Source: Department of the Environment, 1974, 1991; ODPM, 2002.

In contrast, Laune (1990: 35) notes that, far from taking a lead, general needs housing associations rarely considered disabled people as potential tenants and, as he concluded, ‘it is difficult to find examples of good practice with regard to housing provision for disabled people within general needs housing associations’. If anything, a combination of social and political changes since the late 1980s has exacerbated the difficulties for disabled people in gaining access to dwellings that cater for their needs. A reduction in local authority building programmes, coupled with ‘Right to Buy’ legislation, has reduced the quantity of properties in the sector that is most likely to provide for disabled people’s needs.7 This was the principal observation of the Ewing Inquiry (1994: 31) which, in investigating the housing circumstances of disabled people in Scotland, noted that ‘disabled people have little choice in housing … this situation is getting worse because of Right to Buy and because the needs of disabled people are insufficiently recognised’.8

The shortage of accessible dwellings was exacerbated by the practices of the private sector. The legislation tended to ignore the activities of private housing developers, and did little to regulate for access in new housing built for sale (see Chapters 3 and 5, and section 1.3). Morris (1990: 12) notes that, apart from the construction of a few private-sector sheltered housing schemes, there was ‘no record of housing being built to wheel-chair or mobility standards in the private sector’. This reflected a broader, long-term, pattern whereby standards relating to the quality of housing in the private sector were never subject to stringent levels of government regulation. Rather, governments assumed that house builders were best able to identify and respond to consumer preferences in relation to house design and quality issues without recourse to regulation. Regulation was seen, so builders and their representatives argued, as adding to costs and stifling design innovation and responsiveness to shifting patterns of demand (see, for example, House Builders Federation, 1995).

Consequently, self-regulation through voluntary codes of practice was paramount in relation to issues about housing quality, disability and access. For instance, in 1981 the National House Building Council (NHBC, 1981) issued an advisory note to builders asking them to make new dwellings more suitable for elderly and disabled occupants.9 Likewise, in 1982 the House Builders Federation (HBF, 1982) published its ‘Charter for the Disabled’, which encouraged builders to respond to the design needs of disabled people. Such documents were little more than advice to builders ‘on avoiding the worst’ (Goodchild and Karn, 1997: 165), and were usually ignored because, as Borsay (1986) suggests, builders do not regard disabled people as a sufficiently large enough market to build speculatively for them. By the early 1990s it was clear that builders were failing to respond to advisory notes and other miscellaneous advice about disabled people’s access to housing, and, as Barnes (1991: 158) observed, ‘the stock of inaccessible housing continues to grow’.

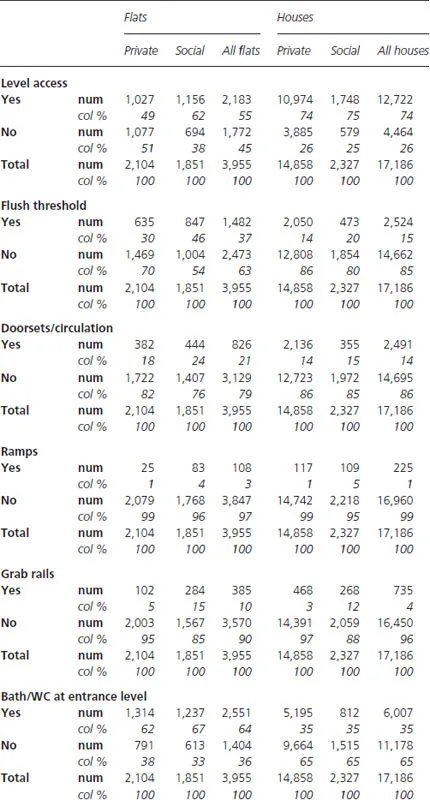

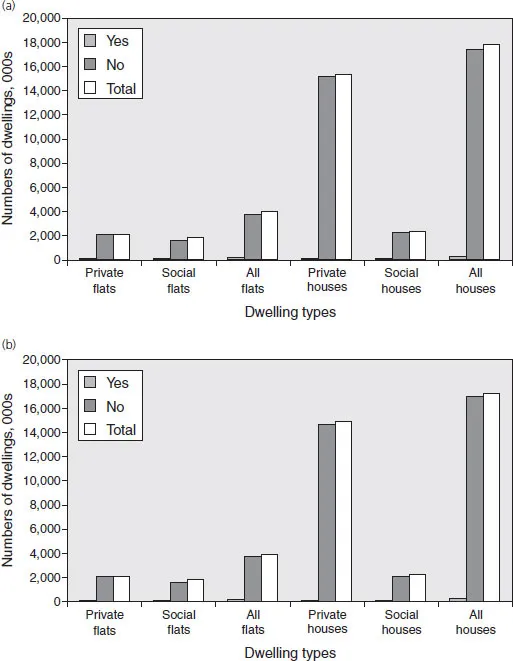

For many disabled people, their functional capacities are potentially reduced by inaccessible dwellings. King’s (1999) research of the housing circumstances of 478 wheelchair users in the UK shows that their dwellings did not fully meet their needs and that most said that they wanted to move.10 Chamba et al.’s (1999) study also notes that in ethnic minority households with a mobility-impaired child, three out of five families stated that their home was unsuitable for their disabled child’s needs. Only a quarter of the sample were able to afford to make adaptations to their home, and most of these were homeowners. Not surprisingly, the English House Condition Survey (EHCS) (ODPM, 2002) shows that only 7,000 dwellings in England have the design features that are seen by government as comprising the minimum requirements for wheelchair accessibility in dwellings (i.e. a level threshold, level access to the dwelling, a WC on the entrance storey, and 750 mm clear door openings), and that most of these are in the social rented sector (see Table 1.1, Appendix 2).11

Table 1.1 Dwellings (000s) having features or adaptations making them more suitable for use by people with disabilities, 2001.

Source: English House Condition Survey, ODPM (2001).

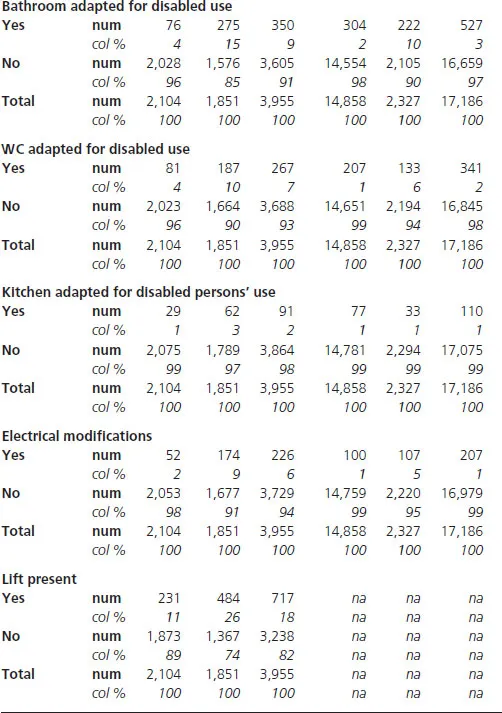

The implication is that most of the dwelling stock in the UK, and elsewhere, is not designed to respond to the needs of people with different types of impairment (see also Karn and Sheridan, 1994). This is particularly so with regard to individuals with mobility impairments, and where the use of a wheelchair is required. For instance, Figure 1.3 (page 20) shows that 1 per cent of private flats and houses in England in 2001 had ramped access, and only 1 per cent of private houses had a WC converted for disabled people to use (ODPM, 2002).12 Likewise, the Scottish House Condition Survey (Scottish Office, 1996) estimated that only 5,000 dwellings met wheelchair accessibility standards, with less than 40 per cent of these occupied by wheelchair users.13 A similar survey, of housing and planning needs in Bournemouth in the UK, revealed that nearly two-thirds (62 per cent) of those relying on a wheelchair lived in homes not suited to wheel-chair use (Bournemouth Borough Council, 1998). Only a quarter (25 per cent) of wheelchair users lived in dwellings that had been adapted.14

1.3 Dwellings having features or adaptations making them more suitable for use by disabled people, 2001.

(a) Dwellings in England with ramped access.

(b) Dwellings in England with a WC adapted for use by disabled people Source: ODPM, 2002.

Such disadvantage is portrayed by some researchers and government officials as the result of the debilitating effects of impairment, or the physiological deficit or medical problems that individual disabled people have. The prognosis is that disabled people ought to be subject to medical intervention, care and, ideally, cure and rehabilitation to ensure that they are able to fit into and interact with the prevalent patterns of domestic design. In this scenario, the problems relating to inaccessible dwellings are ,,less to do with the broader processes shaping the nature of domestic design, and more the outcome of individual bodily deficits or deficiencies. Impairment, and the individuals it resides within, is the causal mechanism, or the matter that determines disabled people’s experiences ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Notes on the author

- Acknowledgements

- Illustration credits

- Introduction

- Part I Concepts and Contexts

- Part II Securing Accessible Homes

- Part III Promoting Accessible Housing

- Endnotes

- Appendices

- References

- Index