![]()

Chapter One

Introduction

Stephen Marshall

Cities exhibit a typical mix of order and diversity: more order than a random aggregate of architecture; more diversity than an artefact crafted by a single hand. Manhattan’s classically craggy silhouette of skyscrapers can be seen as a motley agglomeration of forms, styles and materials, reflecting the idiosyncrasies of individual aspirations, location decisions, market forces and architectural flights of fancy. But this diversity is framed by a certain kind of order, or rather two kinds of order: one to do with urban plans, the other to do with urban codes (figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1. The physical fabric of Manhattan is ordered both by the ground plan and the use of codes. (Source: © Joel Sartore/joelsartore.com)

Manhattan has a spectacularly regular street grid – a relentless orthogonal plat of hundreds of rectangular blocks, following the Commissioners’ grand plan of 1811.1 Yet the orthogonal ground plan is not the only kind of order we can discern. There is also a certain kind of order to do with the height of the buildings, their materials, façades, how these relate to the street, how much of their plot is built out, and what percentage of the block continues above a certain height (see chapter 11). This is a different kind of order, one generated by urban codes.

Codes are part of the ‘hidden language of place-making’. They have a direct influence on ‘the structure of the ordinary’ – where ordinary connotes something not insignificant, but rather something representing the vast majority of the urban fabric.2 Urban codes are therefore important because they significantly shape the character of our urban areas – for better or worse.

On the one hand, some of our best-loved urban places have been created through some kind of urban codes. On the other hand, some of the problems with contemporary urban environments may be related to the influence of codes – such as those ‘disurban’ codes that produce use-segregated, pedestrian-unfriendly placeless landscapes. Those codes were well-intentioned, but their rationales no longer support the aspirations of today. In recent years the significance of urban codes has been brought into sharp focus, as incumbent instruments ripe for reform, or new tools for shaping the future (Talen, 2009, p. 144).3

In the United Kingdom, the government has advocated codes for their potential to assist with speed, quality and certainty in the delivery of the current generation of large-scale urban development programmes. Codes have also been advocated for promoting particular kinds of physical fabric and public realm. Codes have been used in the Prince of Wales’s model community of Poundbury and in a variety of other innovative projects in the UK (CABE, 2005; Carmona et al., 2006b, p. 210; Carmona and Dann, 2007; DCLG, 2006, 2009).4

In the United States, New Urbanists have pioneered a new breed of urban codes that have challenged conventional kinds of zoning ordinances, to create better, more ‘liveable’ urban environments. In particular, form-based coding has emerged to establish new conventions for codes to control the form and layout of urban development through tools such as building typologies, public space standards and control of architectural components. In fact, form-based coding is not just about controlling the form of the urban fabric, but can be seen as an alternative approach to the process of creating the urban fabric. Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk has proclaimed form-based coding to be a ‘new city-making approach’. This takes coding directly into the realm of planning (Plater-Zyberk, 2008).5

Planning and coding have an intertwined history. Towns and cities that we think of as being planned are not just regular and orderly through their ground plan, but through their building types, heights and materials, that are controlled by codes. Indeed, codes have often been instrumental in the creation of planned towns and cities. But, since the advent of modern planning, there has often been more emphasis on individually designed buildings or wholly master-planned developments, and a rejection of the kind of interlocking street-based urban fabric with which codes have historically been associated. In a sense, there has been no modern theory of how to create street-based urbanism using codes. Further, while coding is now receiving increasing interest, it is not always clear what exactly it means, what its possible formats are, or what it can achieve in conjunction with urban planning. It therefore seems timely to investigate the topic of coding, in relation to planning: hence this book.

In this opening chapter, let us first take a look at urban codes and their relation to plans, and contemporary challenges and critiques facing coding and planning, before looking ahead to the scope and content of the rest of the book.

Seaside sets the Scene

Planning history is punctuated by landmark cases where particular urban places have either exemplified a planning concept of a particular era, or acted as a model for future development. The Miletus grid is often taken to exemplify classical Greek layout planning. Palmanova can be used to signify the geometric order of the ideal cities of the Renaissance. The workers’ villages and towns of Bournville, Port Sunlight and Pullman encapsulate the combination of progress and standardization associated with the industrial revolution. Radburn, New Jersey, gives its name to any number of generic suburban layouts with a system of dedicated pedestrian and vehicular routes. Brasilia symbolizes not only new city-building but post-colonial nation-building (see, for example, Lynch, 1981; Hall, 2002a; Kostof, 1991; Morris, 1994).

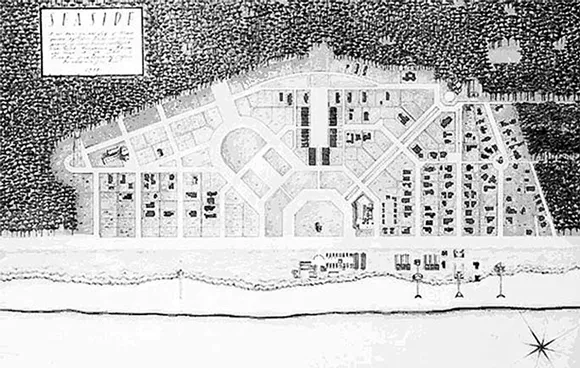

The development at Seaside, Florida, seems to have acquired some of the status of these landmark set-pieces (Ellis, 1988; Duany et al., 1989).6 The significance of Seaside is two-fold. Perhaps most prominently, Seaside is famous for being an early agenda-setting example of a particular brand of neo-traditional urbanism – which was to become New Urbanism – based on a traditional, street-gridded, mixed-use community. Figure 1.2 gives the flavour of the quasi-baroque, neo-traditional feel of the place from its artistically rendered site plan.

Figure 1.2. Plan of Seaside. (Source: Jean-François Lejeune)

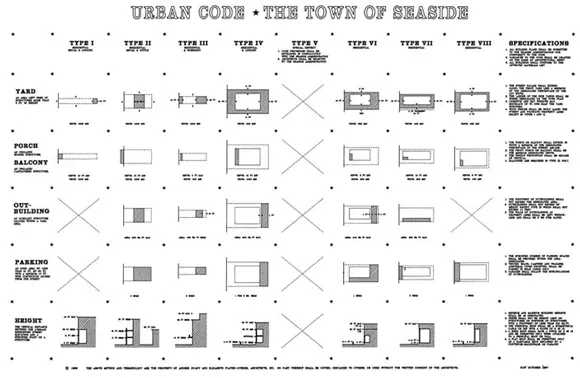

But secondly, Seaside is significant for its use of codes; in particular, the reinvention or revival of codes prescribing three-dimensional forms and urban components.7 Figure 1.3 depicts Seaside’s ‘urban code’ that specifies standards for plot size, area and location of open space, porches, outbuildings, parking and building heights. As John Dutton has pointed out, the Seaside urban code was remarkable for its brevity and abstraction. Like a black-and-white two-dimensional bar code for urbanism, the Seaside code can be fitted onto a single sheet of paper (Dutton, 2000, p. 78; Parolek et al., 2008, p. 10).

Figure 1.3. The ‘Urban Code’ of Seaside. (Source: Duany and Plater-Zyberk Architects)

The code features buildings and parts of buildings. But, as John Dutton relates: ‘The code, even in its architectural details, was primarily in support of an urban vision’ (Dutton, 2000, p. 78, original emphasis). This brings home that codes are not just about detailed design, but reach out to address the compass of town planning.

Yet, there is a crucial distinction between a code and a plan. Dutton continues:

Codes do not stipulate an entire ‘designed’ project, with each building designed in detail. Rather, the code fixes certain infrastructural aspects of the design, such as streets, blocks, platting, and open spaces, and governs the parameters of others. (Ibid., emphasis added)

So a code is not a design, but a specification of generic elements and their relationships. Dutton continues, reflecting on the use and purpose for which codes are suitable:

The establishment of the urban infrastructure, whether of small urban infill or a large new town, allows for a project’s realization by many participants over a long duration of time. A level of conformity to the original vision is thereby ensured through the interpretations and expression of individually designed elements. (Ibid., emphasis added)

This brings in dimensions of scale, timescale and achieving coherence while involving several actors. Overall, this combination of attributes – embodied in the case of Seaside – draws attention to several issues concerning coding that are of interest to wider concerns of planning and design.

First, coding may be part of a planning or design process but it is, in principle, a distinct means of generating urban order in its own right. The contrast between figure 1.2 and figure 1.3 is crucial to understanding the significance of coding in contradistinction to other kinds of planning, as a means of generating urban order. Figure 1.2 shows a plan depicting a finite product, where each depicted element corresponds to a unique location; figure 1.3 shows depictions of elemental types and relationships, for example relating building type to building height and specification of associated yards and out-buildings. This code could be used to create an indefinitely large urban product, and one where each individual element could refer to many different cases built out on the ground.8

Secondly, codes deal with different scales: the specification of building components to achieve desired building types or street types, the specification of building types or street types to generate a desired urban form overall. In effect, with an urban code, the scale of intention is urban, but the scale of intervention is at the level of buildings and streets, and indeed individual component parts of buildings.

Third, codes tend to be applied on an area-wide basis – typically being applied by several architects or developers, for example, rather than to a single site controlled by a single design team. Whereas a blueprint or master plan represents the designed product at a single targeted point in time – omitting intermediate or subsequent stages – codes are typically intended as a guide to ongoing or long-term management of a development, not just a single act of conception followed through to construction.

Fourth, because of the type and scale of element involved, codes tend to engage a range of ‘urban design professions’ – typically including architects, planners and urban designers, but also potentially including landscape architects, engineers, traffic analysts, retail and real estate analysts, environmental designers, and so on (Parolek et al., 2008, p. 98; Carmona, 2009, pp. 2660–2661).

It is no surprise to find codes associated with traditional and neo-traditional urbanism, since an urban fabric of streets and squares implies a close relationship between ensembles of buildings and public spaces. However, coding does not necessarily imply traditional or neo-traditional formats; codes can promote modern formats and styles too (Camona et al., 2006b, p. 223; Marshall, 2005b).

The Seaside code can be seen as part of a ‘proactive vision’ for shaping public space. The code aimed to achieve harmony in architectural form, while leaving the design of the individual buildings to others so as to encourage variety (Duany et al., 2000; Krieger and Lennertz, 1991, cited in Grant, 2006, p. 83).

This idea of harmony (or uniformity) with variety (or diversity) is a recurring theme in architecture and wider philosophy, and can be related to Enlightenment thinking. For example, Francis Hutcheson advanced the idea of beauty being founded on ‘uniformity amidst variety’ (Hutcheson, 1725, p. 210; see also McKean, chapter 3, this volume). He applied this to geometric figures, to ‘works of nature’, and also to works of art, and all manner of objects down to the ‘meanest utensil’. So, too in architecture, across cultures:

The Chinese or Persian buildings are not like the Grecian and Roman, and yet the former has its uniformity of the various parts to each other, and to the whole, as well as the latter. (Hutcheson, 1725, p. 219)

Although Hutcheson here is addressing architecture in the context of visual appeal, the idea of uniformity amidst variety can also translate across to the public versus private realm. That is to say, the idea can relate to the extent to which society should have some sort of balance between the variety created by rampant individualism and state-imposed uniformity. Indeed, Dutton (2009, p, 79) explicitly notes that ‘These codes can therefore be seen as an attempt at a new synthetic proposal for balancing the community (unity through parameters of code) with the individual (freedom of architectural expression)’.

The concept of ‘uniformity amidst variety’ can therefore be related to at least two different aspects of urbanism: the physical design, to do with the visual effect of harmonious streetscapes and façades and buildings and ornamentation – in short, to do with aesthetics; and the ultimate social purpose to do with mediating between public and private interests (or individual versus common good). This brings together the purposes of coding with the purposes of planning.

Coding and Planning

In essence, coding generates urban order by the generic specification of allowable and necessary components and relationships. The term urban coding could be used in a general sense to mean the application of any kind of code used in the urban context. In this way, any design code, building code, layout code or zoning co...