eBook - ePub

Production House Cinema

Starting and Running Your Own Cinematic Storytelling Business

- 222 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

In Production House Cinema: Starting and Running Your Own Cinematic Storytelling Business, renowned video storyteller Kurt Lancaster offers both students and professionals a practical guide to starting their own video production company and creating cinematic, client-based video content. Utilizing practical know-how along with in-depth analysis and interviews with successful independent production houses like Stillmotion and Zandrak, Lancaster follows the logistics and inspiration of creating production house cinema from the initial client pitch all the way through financing and distribution. The book includes:

- An examination of the cinematic and narrative style and how to create it;

- A discussion of the legal procedures and documents necessary for starting and operating a production house;

- Advice on crafting a portfolio, reel, and website that both demonstrates your unique style and vision and attracts clients;

- A guide to the financial business of running an independent production house, including invoicing, accounting, and taxes—and how much you should charge clients;

- Tips for how to better communicate with clients, and how to develop and shape a client's story;

- A breakdown of how to select the right gear and equipment for a shoot, on budget;

- Cinematic case studies that offer detailed coverage of several short films made for clients.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Production House Cinema by Kurt Lancaster in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Film & Video. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Creating Your Own Independent Production House Business

Chapter 1

Telling versus Showing

The Tools of Cinema in Client-Based Storytelling

What specifically is the cinematic style? How is it different from some mainstream commercial work? I start here since the premise of the book hinges on an understanding and definition of the cinematic style, what it means, and how you can apply it to client-based work. I start by examining a couple of moments from a 60 Minutes piece and a promotional work in order to show the difference in style when a work is created from narration and a work created cinematically (using shots, voice, sound design, and editing for rhythm). In addition, I look at Stillmotion’s concept of the psychology of the lens—the importance of choosing the right lens for a shot, as well as charts defining and showing how different types of camera movement, shot sizes, angles, and lenses impact how audiences perceive the psychology of a scene. This is followed by a description of Stillmotion’s MUSE storytelling process. In short, I examine some of the tools of filmmakers in order to drive home the understanding needed to create cinematic-style client-based stories.

The Narration Style

Commercial narration and news narration are similar—they share a broadcast style that grew out of radio news broadcasts where words told stories through descriptions of action. News reels—some heavy with propaganda—during World War II perfected this style. Education films from the 1950s to the 1970s brought this style to film in public schools. Images were mainly used to illustrate what the narration—the omniscient “voice of God” style—told the viewer.1 Words told the story. Images illustrated the story like decorative wallpaper. Most commercials and television news follow this narration-driven style.2 In cinema, visuals (along with a compelling audio design) tell the story and words are frosting on the cake—take them away and you can still follow the emotional structure of the story through the shots and soundscape. Words, narration, and dialogue—when used cinematically—sweeten that visual and sonic structure.

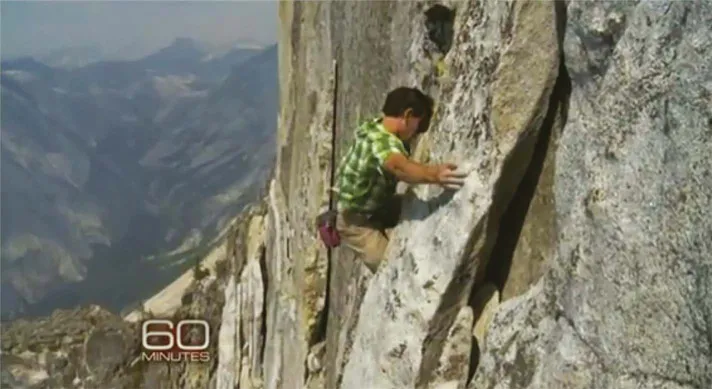

To illustrate this style, I’ll look at a couple of moments from Lara Logan’s “The ascent of Alex Honnold”3 from CBS’s 60 Minutes. It tells the story of Alex’s insane free solo climbs that, in Logan’s words, sets the tone: “He scales walls higher than the Empire State building, and he does it without any ropes or protection” (Logan and Newton, 2011). I compare this work of journalism with a staged promotional film by Tyler Stableford, “Shattered,”4 which tells the story of another climber, Steve House, who looks like he is climbing ice without rope. Both of these projects offer compelling stories told in two different ways.

Perhaps comparing the two isn’t necessarily fair.5 This book isn’t really about journalism, but what I find interesting is how commercials and promotional shorts sometimes mimic the narration-based style of broadcast journalism (from shorts produced on The Weather Channel to 60 Minutes). Since Stableford’s brilliant promotional short is a great example of cinematic client-based work, I really like how it contrasts with the real news story. So why compare the two? Because the style of the broadcast news piece—heavy with narration that tells us what’s going on—is a stylistic choice, not a hard and fast rule in nonfiction work. And since it’s a choice in style, the audience will perceive the story differently than in a film produced in a cinematic style. The comparison and contrast works, because I’m focusing on how the respective stylistic choices between the two impact an audience differently.6

The key point I want to make is how different techniques work and impact audiences so that we can avoid what doesn’t work and apply what does work in order to improve our own projects and learn how to use the best tools to capture an audience’s attention. As Wes Pope, who teaches Multimedia Journalism at the University of Oregon, notes, different storytellers blend different approaches. He describes at least five styles of documentary storytelling alone: “journalistic, interview driven, cinema vérité, reenactment, and reflexive.” Production house producers should be aware of different styles (whether it’s from news, documentary, or fiction) and apply elements from these different styles in order to best shape the stories they need to tell for their clients. For example, both Stillmotion and Zandrak produced work that utilize fiction and documentary techniques, the former in a book promotion, the latter for an app commercial (both covered as case studies in Chapters 8 and 9). 60 Minutes could have chosen to emphasize more cinematic techniques and focus less on the omniscient narration style—but that’s what they do. In the process they lose some of the potential cinematic magic (and perhaps maintain journalistic integrity—but that stylistic argument is open to debate).

Cinematic Techniques

These are four major tools filmmakers use to help create cinematic experiences:

- Shots—the visuals—are designed to tell the story. There are a wide variety of shot sizes and camera angles used to create stories—from extreme wide shots to extreme close-ups. Many filmmakers provide coverage (shooting a range of shot sizes and camera angles in order to give the editor more choices in editing)—and make sure everything gets covered. Specific shots capture specific emotional moments, providing a visual storytelling palate for the editor. (If visuals don’t carry the story emotionally, then you get the wallpaper effect—shots used to decorate the words of a narrator, thus nearly any type of shot would do.) This also includes camera movement. (See the latter part of this chapter for a detailed examination of the psychological effects of camera angles, camera movement, and lenses.)

- Voices of characters. Characters are the ones who speak—not an omniscient “voice of God” narrator.

- Sound design. Ambient audio collected in the field or used from sound libraries—as well as using the right piece of music at the right time (the proper emotional shift occurring in a story)—helps immerse the audience into the world of the story. If there is little to no forethought or design of the sonic landscape of the film, then you’ve thrown away half of the resources of a filmmaker and lost one of the most powerful tools a filmmaker can use. (Check out Michael Ondaatje’s The Conversations: Walter Murch and the Art of Editing Film, Knopf, 2002 and the transom.org interview with Murch at: http://transom.org/2005/walter-murch/.) Studying both of these will prove a treasure-trove for those wanting to dig deeper into cinematic storytelling.

- Editing for pacing and rhythm. The editor’s job, says Karen Pearlman in her work Cutting Rhythms (Focal Press, 2009: 58), is to shape moments of tension and release in the audience by crafting “the rise and fall over time of intensity of energy.” There are many good books on editing, but this kernel of wisdom continues to echo as a universal principle for nearly all editing projects. This includes the shaping of audio and visuals in such a way that the audience is pulled into the world of the film and taken for a ride. Both visuals and the sonic landscape must be treated equally in the edit in order to pull off an effective experience for an audience.

Narration and Decorative Shots

If narration is used improperly—when it tells the story rather than helps enlighten the story—we begin to lose the power of cinematic techniques and we may fail to pull the audience into the story. An example of this occurs at 2:25–2:53, at the climax of Alex’s ascent in the 60 Minutes work, “The Ascent of Alex Honnold.” We hear Logan’s words as we see five shots, her voice is in italics (see Figures 1.1–1.5):

This is Alex in the film, Alone on the Wall. He’s done more than a thousand free-solo climbs, but none were tougher than this one. [This narration provides context and is ok.]

Figure 1.1 Courtesy of 60 Minutes.

Here he is, just a speck on the northwest face of Half Dome: [We see this in the shot, so we don’t need someone to tell us about it.]

Figure 1.2 Courtesy of 60 Minutes.

You can barely make out the Yosemite Valley Floor below, as he pauses to rest: [Again, the visuals—along with a strong sonic landscape—pull us into a story, while narration that tells us what we’re seeing and hearing pushes us out of a story.]

Figure 1.3 Courtesy of 60 Minutes.

He’s the only person known to have free-soloed the northwest face of Half Dome. [Pan and tilt up for next two images]: [This narration provides context, so it is ok.]

Figure 1.4 Courtesy of 60 Minutes.

Figure 1.5 Courtesy of 60 Minutes.

Overall, these shots are good—some are even strong—but their impact is lost in the narration.

In another segment, where Honnold is hanging on another cliff face, we hear this from Logan (see Figure 1.6): “Alex moves seamlessly across a section of flaky, unstable rock, pausing to dry a sweaty hand in his bag of chalk. There’s nothing but him, the wall, and the wind.” But all of this can be seen and heard, while the narration gets in the way of the cinematic possibilities of this moment. We hear breathing and some ambient wind but the audio mix doesn’t make it stand out, because it is lost in the voiceover. In addition, the cinematographer could have zoomed in to a close-up so we could see Honnold’s expression, visually driving home the moment. But the narration does it for us.

The cinematic impact of a close-up and a sound design has no priority. Instead, the producers chose to allow a narration to tell this part of the story. This is a stylistic choice and for those who want to engage in cinematic-style stories in production house work, it’s the wrong choice. The right choice would stem from this key question: What does it feel like to hang on the face of a cliff thousands of feet off the ground?

A cinematic approach would have forced the thinking about what kinds of visuals and audio are needed to answer this question. Perhaps this moment could have been told by the subject (through Honnold’s voice, rather than a narrator).

Notice that with this narration, it doesn’t matter what type of shot we see of Honnold. Any shot of him on the wall reaching into the chalk bag fulfills the requirement of decorating the narration—thus it’s called wallpaper.

Figure 1.6 Logan’s voice in “The Ascent of Alex Honnold” tells us what Alex does in a play-by-play style.

(Courtesy of 60 Minutes.)

(Courtesy of 60 Minutes.)

By making the choice to engage in a voiceover narration style instead of a cinematic style, the emotional power of this scene fizzles. This same kind of mistake7 is made countless times in commercials and promotional shorts as well. For example, in a local 30-second commercial for Central Fresh Market we see in the second shot a woman holding a basket and an orange pepper as she looks at the camera and smiles, stating, “I shop here because the fresh meats, fruits, and vegetables make meal planning a breeze” (see https://youtu.be/n0uyaAgl-Hk and Figure 1.7). This is narration masquerading as dialogue and I include it as a warning. You may have characters speak with no narration, but if they’re selling a product in the dialogue—then it fails the cinematic test (and becomes the kind of stuff I muted out as a child and still avoid watching, today). We know when the cinematic style is...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- About the Author

- Acknowledgments

- Foreword

- Introduction: The Business of Cinematic Storytelling in a Video Production House

- PART I Creating your own Independent Video Production House Business

- PART II Running an Independent Production House Business

- PART III Crafting the Cinematic Style: Case Studies

- Notes

- References

- Index