- 192 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

As the full effects of human activity on Earth's life-support systems are revealed by science, the question of whether we can change, fundamentally, our relationship with nature becomes increasingly urgent. Just as important as an understanding of our environment, is an understanding of ourselves, of the kinds of beings we are and why we act as we do. In Loving Nature Kay Milton considers why some people in Western societies grow up to be nature lovers, actively concerned about the welfare and future of plants, animals, ecosystems and nature in general, while others seem indifferent or intent on destroying these things. Drawing on findings and ideas from anthropology, psychology, cognitive science and philosophy, the author discusses how we come to understand nature as we do, and above all, how we develop emotional commitments to it. Anthropologists, in recent years, have tended to suggest that our understanding of the world is shaped solely by the culture in which we live. Controversially Kay Milton argues that it is shaped by direct experience in which emotion plays an essential role. The author argues that the conventional opposition between emotion and rationality in western culture is a myth. The effect of this myth has been to support a market economy which systematically destroys nature, and to exclude from public decision making the kinds of emotional attachments that support more environmentally sensitive ways of living. A better understanding of ourselves, as fundamentally emotional beings, could give such ways of living the respect they need.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Loving Nature by Kay Milton in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Anthropology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

SCIENCE AND RELIGION

The hope that science could replace religion as a way for human beings to cope with the world . . . was really a hope that ‘nature’ could replace ‘God’ as a source of inspiration and understanding. Harmony, permanence, order, and an idea of our place in that order – scientists searched for all that as diligently as Job, with their unceasing attention to the ‘web of life’ and the grand cycle of decay and rebirth. But nature, it turned out, was fragile.

(McKibben 1990: 76–7)

For as long as I can remember, I have been surrounded by people who take an active interest in the protection of nature and natural things. During the past fifteen years, when environmentalism has been my main research interest, I have spent many hours reading reports, policies and campaign literature produced by nature protection authorities and NGOs, and engaged in debates about these documents. I have attended many formal and informal gatherings at which nature protection has been discussed, and had many conversations with nature protectionists about their activities. I have also, in the pursuit of work and pleasure, been an enthusiastic consumer of books, magazines, television programmes and, more recently, websites, aimed at increasing public concern for nature. One of the clear impressions gained from all this exposure is that nature protectionists relate to nature in ways that can be described, broadly, as ‘religious’ or ‘scientific’. These two idioms do not, by any means, exhaust ways of relating to nature, but they are prominently expressed in discourses about nature protection. This observation creates an interesting possibility. Debates about the differences between religion and science have arisen repeatedly in anthropology and related disciplines throughout the past century. Perhaps this academic discourse could provide an appropriate vehicle for thinking about how nature protectionists relate to nature, a way of identifying key ideas that might help us to understand how people engaged in the protection of nature come to think, feel and act as they do towards the objects of their concern.

In this chapter, I explore this possibility by analysing what anthropologists and other specialists have written about the relationship between science and religion. There are three tasks to be accomplished. First, I need to show that both scientific and religious ways of relating to nature are present in discourses about nature protection; this task occupies the next section. Second, I need to identify those ideas about science and religion that might be useful in explaining what motivates nature protection. This task, which occupies most of the chapter, takes the form of a discussion of what has been written about science, religion, their relation to each other and to other kinds of cultural perspective (magic and common sense). Three pairs of contrasting or opposed concepts emerge from this discussion: natural and unnatural ideas, personal and impersonal understandings of nature, and emotion and rationality. Finally, I need to suggest ways in which these oppositions might be relevant for understanding nature protection. These thoughts are drawn together in the final section which identifies the issues to be addressed in the following chapters.

Science, religion and nature protection

My starting point is the observation that nature protectionists relate to nature and natural things in both scientific and religious ways. This means, essentially, that they talk and write about nature, and act towards it, in ways that conform to commonsense understandings of what science and religion consist of. In the following sections it will become important to indicate how anthropologists and other scholars have defined science and religion, but for the present I am using these labels rather loosely and taking their meanings for granted. I am assuming that ‘science’ will conjure up in most readers’ minds a body of knowledge generated through systematic observation, knowledge which is seen as authoritative because of the controlled manner in which it is generated. And I assume that ‘religion’ will suggest a concern with ultimate meanings as a basis for moral rules, rules which are often, though not always, believed to be sanctioned by a sacred authority, in the form of a divine being or beings.

The close relationship between science and some forms of nature protection is so taken for granted that it is difficult to describe it without seeming to state the obvious.1 Problems in nature are defined as such on the basis of scientific knowledge. We know about pollution, ozone depletion and climate change because scientists have told us about them. Science explains how these problems have arisen and what might be done to solve them. Some nature protectionists, those whom I shall refer to throughout this book as ‘nature conservationists’ (or simply ‘conservationists’), employ a scientific model of nature as an array of living and non-living things and substances which interact with one another. Many of the terms which conservationists use to describe the components of nature – species, ecosystem, habitat, biodiversity – come from science. According to science, biodiversity is good for the future of life on earth because, in accordance with Darwinian theory, the greater the variety of living things there are, the greater the chance that some will adapt and survive in a changing environment. Some conservationists describe this as the most important reason for conserving nature, a point to which I shall return in later chapters. Science indicates what specific organisms need for their survival, enabling conservationists to define objectives for the preservation and restoration of species and habitats.

In summary, the main function of science in nature protection is to be used as an arbiter of truth. Even though scientific knowledge is open-ended and constantly changing (see below), it is treated by environmental activists and policy makers as the main authority on the state of nature, and therefore as the most reliable foundation on which to base decisions. Its importance as a basis for decision making rests on the belief – one that has often been questioned by social scientists – that science can provide impartial knowledge (Berglund 1998: 193), a point to be explored further in Chapter 8.

The role of religion in nature protection is harder to describe, perhaps because religion is a less precise concept than science. Some branches of nature protection have features which are generally associated with religion. In some of the most influential writing (for instance, Carson 1956, Seed et al. 1988, Macy 1991, Spangler 1993),2 the sustenance of life on earth is presented, both explicitly and implicitly, as a sacred purpose, and the protection of nature as a spiritual commitment to that purpose. This is particularly so for those who see the modern development of technology, based on science, as the main cause of environmental destruction, and who seek fundamental changes in the way people in western society relate to nature. Deep ecologists, who fall within this broad category, have argued that science and technology have ‘disenchanted’ nature, destroying the sense of respect and awe with which it was once treated. They seek a ‘reenchantment’ of nature, a restoration of respect and the establishment of harmony in human–nature relations (Barry 1999: 17). Some turn to non-industrial societies for models of a more appropriate relationship with nature (for instance, Manes 1990: 28, Ereira 1990); often these are hunter-gatherer cultures in which nature is ‘enspirited’ (Callicott 1982: 305), in which relationships between people and their environments are governed by moral obligations on both sides (see Tanner 1979, Scott 1989).3

As well as some of the ways in which protectionists relate to nature having what might be called religious characteristics, organized religion has featured in discourse on nature protection, both as an object of criticism and as a positive influence. White (1967) is among many who have held Christianity at least partly responsible for western society’s exploitation of nature, and who have compared it unfavourably, in this respect, with other religions. Recognizing the powerful influence of religion in the lives of many people, nature protectionists have sought to enlist religious world views in the promotion of an environmental ethic (Tucker 1997). This approach was exemplified in the World Wide Fund for Nature’s Network on Conservation and Religion (WWF 1986), which brought religious leaders together to discuss ways in which their various doctrines could support the cause of conservation. Religious leaders and church organizations have also, on their own initiative, expressed their concern for nature and sought to define their role in its protection, often against the background of broader national and international discussions such as the Rio Earth Summit in 1992 (see, for instance, Gottlieb 1996: 636ff.).

It is tempting to oversimplify the relationship between science and religion in nature protection by suggesting that, while science provides the knowledge on which actions are based, religion provides their moral justification. Some of the discussion among nature protectionists is along these lines. For instance, Callicott (1994) argued that science should form the basis for environmental ethics with religion playing a supporting role, while Taylor (1997) argued that scientific knowledge cannot provide people with moral values (cf. Yearley 1992: 144), and that religion provides the only sound basis for moral motivation. But many nature protectionists value ways of knowing nature other than science, and there are other bases for morality besides what is conventionally regarded as religion (Barry 1999: 38ff.). These issues will be addressed in the following chapters. The remainder of this chapter focuses on the relationship between science and religion, as a vehicle for thinking about ways of relating to nature.

Science, religion and magic

‘Is magic a kind of science or a kind of religion?’ Through this question, some thirty years ago, I and my fellow anthropology undergraduates were introduced to one of the discipline’s early debates. The quest, which remains central to anthropology, was to reach a better understanding of human culture by comparing the familiar with the exotic. Magic was the exotic. It had no place in our everyday lives; it was something that only societies distant in time or space took seriously. Religion and science, in contrast, were familiar. Both had figured prominently in our formal education, were featured in the media, and had inspired films and popular fiction. For some of us, religion was a personal commitment.

The main protagonists in that early debate were Tylor, Frazer and Malinowski. For Tylor and Frazer, magic was a pseudo-science. Its status as such depended on two features of magical thought: like science it was logical and systematic, but unlike science it was fallacious. It had the character of science but not its truth. In Tylor’s words, it was ‘a sincere but fallacious system of philosophy, evolved by the human intellect by processes still in great measure intelligible to our own minds’ (Tylor 1871, vol. i: 122). For Frazer, the principles of magical thought were:

excellent in themselves, and indeed absolutely essential to the working of the human mind. Legitimately applied they yield science; illegitimately applied they yield magic, the bastard sister of science. It is therefore a truism, almost a tautology, to say that all magic is necessarily false and barren; for, were it ever to become true and fruitful, it would no longer be magic but science.

(Frazer 1994: 46)4

Malinowski also recognized a degree of similarity between magic and science (Malinowski 1948: 67), but saw their differences as more fundamental than their similarities. For him, they operated in different cultural contexts and fulfilled different functions. Science belonged to the realm of practical, everyday tasks, where it provided solutions through empirical observation and rational thought. But this kind of knowledge was not adequate for all situations. There were problems it could not solve – how to cure a particular illness, how to ensure safety on a sea journey. These gaps in knowledge created emotional stress which magic relieved by providing a set of ready-made beliefs and practices (ibid.: 70). It thus operated, according to Malinowski, in the same way as religion, whose purpose was to relieve the emotional stress created by extreme situations (ibid.: 67). But the similarity between religion and magic rested, not only on the type of problem they solved, but also on the type of solution they provided. Both provided escapes ‘by ritual and belief into the domain of the supernatural’ (ibid.). This placed them, in Malinowski’s view, in the realm of the sacred, in clear opposition to science, which belonged to the realm of the profane.

Our task as undergraduates was to understand the arguments of Tylor, Frazer and Malinowski, their points of agreement and disagreement, how they reached their conclusions. We were not expected to provide a definitive answer to the question of whether magic is a kind of science or a religion, but to understand why it was a question worth asking. I fear that in my naivety, like many young students, I missed the point. The familiarity of science and religion and the strangeness of magic concealed what, with hindsight, seemed quite obvious: that the question was asking as much about the nature of science and religion as it was about the nature of magic.

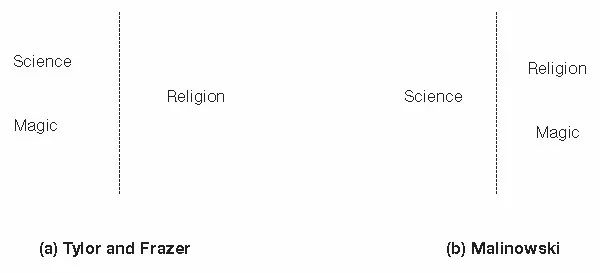

Of course, it is significant that Tylor, Frazer and Malinowski also saw magic as the most problematic of the three concepts. Magic, as the relatively unfamiliar phenomenon, confined to the margins and the history of western society, needed to be investigated in a range of non-western cultures before its place in the broad scheme of things could be determined. Science and religion were at least familiar if not easy to define, given the diversity of opinions about them. Because they were familiar, they could be used as fixed points against which the unfamiliar could be measured. In the work of all three analysts, science and religion were placed apart, on opposite sides of a dividing line (see Figure 1.1). The work of Tylor, Frazer and Malinowski may not be representative of early anthropological thought (Durkheim and Weber, for instance, identified continuities between science and religion; see Tambiah 1990), but it demonstrates that an opposition between science and religion was present and, to some extent, taken for granted in the formative development of anthropology. The precise nature of that opposition will come under scrutiny below.

Science, religion and common sense

Malinowski’s famous essay on Magic, science and religion, originally published in 1925, began with a bold declaration: ‘There are no peoples however primitive without religion and magic. Nor are there, it must be added at once, any savage races lacking either in the scientific attitude or in science’ (Malinowski 1948: 1). But later in the essay he seemed to draw back from the view that science is universal in human culture. His ‘minimum definition’ of science as ‘a body of rules and conceptions, based on experience and derived from it by logical inference’ (ibid.: 17) was so broad, he acknowledged, that it would not satisfy most epistemologists, and might equally apply to an art or craft. He occasionally used the broader term ‘rational knowledge’ in favour of ‘science’, and admitted that ‘whether we should call it science or only empirical and rational knowledge is not of primary importance’ (ibid.: 18, emphasis in original). Thus he both obscured and hinted at a distinction which has since become important in the analysis of culture: the distinction between science and common sense.

Figure 1.1 Models of science, religion and magic

The phenomenon which Malinowski cautiously labelled ‘science’ (and, less cautiously, ‘rational knowledge’) is now more widely referred to as ‘common sense’ (Horton 1967, Atran 1990). Inevitably, anthropologists mean different things by ‘common sense’. In general, it is assumed to include people’s everyday knowledge. But does this knowledge consist only of ‘manifestly perceivable empirical fact’ (Atran 1990: 1), or is it ‘what the mind filled with presuppositions . . . concludes’ (Geertz 1983: 84)? And where, in any case, should the line be drawn between presupposition and perceivable fact, if it should be drawn at all? These questions will be addressed in Chapters 2 and 3.

‘Science’, meanwhile, through the influence of philosophers, historians (Popper 1965, Kuhn 1970) and practising scientists (Wolpert 1992), is now more narrowly defined than it was by Malinowski, though again, definitions vary. Most would agree that science is a systematic search for knowledge, characterized by induction (verification through observation) and reduction (explanation of phenomena in terms of their progressively smaller components). It is open-ended (Horton 1967), it continually generates new knowledge and it employs a rigorous methodology (Wolpert 1992: 2). According to this view, science has to obey rules which do not constrain common sense.

In more recent debates about science and religion, common sense has replaced magic as the ‘middle ground’ (Richards, P. 1997: 109), the connecting territory through which the similarities and contrasts between science and religion are identified. Horton took this approach in his (1967) comparison between western science and African religious thought. He described both kinds of knowledge as ‘theory’; they seek to explain what lies behind commonsense observations. The understanding provided by common sense leaves a great deal unexplained. Why do some people suffer greater misfortune than others? Why do crops sometimes fail? Theory fills this gap by positing an ordered universe, in which the observable world, with its puzzles and anomalies, is the outcome of a limited number of general principles (Horton 1967: 51). Theory ‘places things in a causal context wider than that provided by common sense’ (ibid.: 53). Where common sense seeks the obvious and immediate cause, theory searches further afield. Common sense tells us that the crop failed because of a storm, but we need theory to explain that the storm was caused by witchcraft, or an angry god, or by unseasonal temperatures produced by carbon dioxide emissions.

What then distinguishes religious from scientific theory? In Horton’s view, the key difference is that scientific theory is open to alternative explanations whereas religious theory is closed (Horton 1967: 155ff.). In religious thought, established theories are accepted truth; it would be inappropriate to question them. It follows from this that religion protects its established ideas (ibid.: 167). The failure of rituals to have the desired effect does not cause people to lose faith in their efficacy. A body of religious theory contains ready-made explanations for failure. Science, on the other hand, not only requires established ideas to be abandoned if they fail, but also requires them to be tested systematically through experiment (ibid.: 172).

Atran also treated common sense as the middle ground between scientific and religious, or in his word ‘symbolic’, thought. Common sense is the means by which people come to know the world through the rational interpretation of information received through their senses. It constitutes a core of basic knowledge on which theory depends (Atran 1990: 265). Like Horton, Atran presented science and symbolism as kinds of speculative theory which employ different rules. Science seeks to understand the unknown in strictly rational ways, by providing evidence which can be confirmed or refuted using the same universal cognitive properties that produce commonsense knowledge – the powers of observation and inductive interpretation. Symbolic thought, in contrast, is not constrained by rationality (Atran 1990: 250), so it cannot be relied upon to produce truthful propositions. Symbolism has no means of testing the truth of its beliefs, and so depends, for its authority, entirely on faith (ibid.: 217). Scientific and symbolic thought are thus ‘diametrically opposed’ in their relation to common sense. Science seeks to augment ‘the rational processing of empirical reality’ while symbolism bypasses it (ibid.: 220). On this basis it seems reasonable to ask how symbolism can be grounded in common sense at all, given its non-rational nature. The relationship, in Atran’s analysis, is one of opposition and contradiction. Symbolic thought challenges common sense in specific, non-random ways (ibid.: 219–20), and is dependent on it in the sense that the counter-intuitive is always dependent, for its meaning, on the intuitive (ibid.: 265).

The continuity, noted by Horton and Atran, between science and common sense was forcefully denied by Wolpert.5 ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1: Science and Religion

- 2: The Naturalness of Ideas

- 3: Knowing Nature Through Experience

- 4: Enjoying Nature

- 5: Identifying with Nature

- 6: Valuing Nature

- 7: Protecting Nature

- 8: Protecting Nature

- Conclusion

- Notes

- References