1 INTRODUCTION

In the 1930s I sent for a dress pattern, costing 4/11 [25p]. I made it up and wore it during my honey moon. In 1943, I sent for a cut-out pink satin nightdress—very glamorous. I wore this after the birth of my second daughter. The cost then was 10/-[50p]. Now when I’ve read your magazine I pass it to my daughter-in-law, who gives it to her mother and aunt. Quite good value, wouldn’t you say?

(Mrs A.F. Smith, Kent, letter to Woman 13 Feb. 1988, 7)

Last week I invited my girl friend to my house for a romantic dinner at which I intended to ask her hand in marriage. I had planned the meal weeks previously but, alas, I forgot one of the major ingredients. Frantically I turned to a copy of Bella that my girl friend had left behind. I came across a recipe for sweet-and-sour bacon chops for which I had all the ingredients. The meal was tremendous and my girl friend was impressed. She also agreed to my proposal. I can’t thank you enough.

(Tony Docherty, letter to Bella, 10 Feb. 1990)

Throughout its history, the woman’s magazine has defined its readers ‘as women. It has taken their gender as axiomatic. Yet that femininity is always represented in the magazines as fractured, not least because it is simultaneously assumed as given and as still to be achieved. Becoming the woman you are is a difficult project for which the magazine has characteristically provided recipes, patterns, narratives and models of the self. Mrs Smith of Kent explained that it was precisely this for which she had valued it over many years. Woman had provided patterns for her to follow as she negotiated the complexities of an identity which encompassed sexual woman, frugal housekeeper and mother. The glamorous nightdress she bought through the magazine enabled her to become a desirable woman without abandoning her role as good housekeeper. For the magazine has historically offered not only to pattern the reader’s gendered identity but to address her desire.

This femininity has been addressed in and through a form which is itself fractured and heterogeneous. The magazine has developed in the two centuries of its history as a miscellany, that is a form marked by variety of tone and constituent parts. The relationship between the two elements in the term ‘woman’s magazine’ has been and is dynamic. The magazine evolved as it did because from its inception it was a genre which addressed ‘the feminine’, but ‘femininity’ has also been informed by the development of print, particularly the magzine. The history of their relationship has been marked by continuity but also by discontinuity and by the constant re-working of the ‘same’ elements whose meanings are radically unstable. Mrs Smith’s letter, with its public revelation of her intimate life, was in a tradition which had been re-worked during 200 years of feminine journalism.

Her letter earned her £5 and the ‘good value’ she identified in the magzine was economic rather than ideological or psychological. Magazines are commodities, products of the print industry. They have also become a crucial site for the advertising and sale of other commodities, whether nightgowns or convenience foods. Magazines are, therefore, deeply involved in capitalist production and consumption as well as circulating in the cultural economy of collective meanings and constructing an identity for the individual reader as gendered and sexual being. The woman’s magazine works at the intersection of these different economies—of money, public discourse and individual desire—and it is there I situate the history I trace in the rest of this book.

Unlike earlier historians of the women’s press, therefore, I do not read the magazines of the last century exclusively as instruments of a pervasive domestic ideology and a regime of sexual repression (Adburgham 1972; White 1970). This reading was embedded in a view of the period wich has since been challenged by historians from a range of positions, including feminists (Barret-Ducrocq 1991; Bland 1995; Foucault 1981; Gay 1984; Shires 1992; Smart 1992). It has also been challenged by the theorising of post-structuralists, notably Foucault, whose theorising of the relationship of discourses to knowledge and power, problematic though it is for feminists, provides some useful tools here (Foucault 1981). In particular his argument that power is prductive and not simply repressive throws light on the complex relationships enacted in women’s magazines between readers, writers and editors.

Mrs Smith’s letter suggests the power of the magazine’s discourses of femininity but it also shows her capacity to exploit them. The magazine itself becomes, for her, a medium of exchange among a community of women, a process which circumvents the economic aims of its producers and reasserts an alternative set of values. Perhaps she is even exploiting her knowledge of the assumptions of the letters page to earn herself £5. Certainly she knows how to play the part of ‘Mrs Smith’, the average woman to whom the magazine is addressed.

Readers may be relatively less powerful than writers but they can still accept or resist meanings the writer produces. Writers are powerful in relation to language and the reader but less so in relation to the editor, the publisher or the advertiser. Editorial power is itself limited, discursively and economically, by pressure from advertisers and from readers. Moreover the balance of power between these different groups varies historically and is constantly in process. In the woman’s magazine, gender and sexuality—yet other complex sets of power relationships—are caught up in these dynamics. Popular print is too complex a phenomenon to be understood in the simplistic terms of ‘patriarchy’ or of ‘class’, and theories of gender which construct women only as victims of repression are theoretically and politically suspect.

To collapse power absolutely into discourse, however, is likewise to oversimplify and to lose sight of the material and political history in which struggles over meaning take place. This means recognising that as commodities magazines are only available to those with the necessary levels of literacy, income, leisure and space for reading. It also means that as texts, magazines enact relations between groups which are very differently situated in the social and cultural structures of power. In the complicated negotiations over meaning which characterise popular print, some groups have more power than others to make their meanings ‘stick’ (Cameron 1986; Thompson 1984). In the rest of this book, readings of specific magazines are situated in unequal power relationships, particularly— but not exclusively—those of gender.

The asymmetry of gender is clearly evident in Tony Docherty’s letter to Bella which forms the other epigraph to this chapter. Throughout its history men have entered the woman’s magazine as readers, writers and editors. It may be that by doing so, they learn to read ‘as women’. Certainly, the magazine provided Tony Docherty with that crucial recipe and with a narrative of romantic encounter. But his reading gave him access not to being a woman but to the feminine world of the domestic and to female sexuality, which he appropriated ‘as a man’. The language of this letter with such phrases as asking her hand in marriage suggests that this appropriation may be ironic, even parodic. Nevertheless the point remains.

Like the nineteenth-century middle-class home, the woman’s magazine evolved during the last century as a ‘feminised space’. It was defined by the woman who was at its centre and by its difference from the masculine world of politics and economics. But whereas the middle-class woman could not enter the public world of work or politics, the middle-class man could and did come home at night to be revived and humanised by his immersion in the domestic world of the feminine. The equation of the feminine with the human—or at least the humane—is only one aspect of the complexity of gender dynamics which the popular magazine enacts. It did not necessarily empower women. The feminised world of the magazine whose history I trace is constantly entered and appropriated by historical men (Modleski 1991). The asymmetry of gender difference therefore recurs throughout this book and is fundamental to its project. It would be impossible to write a comparable history of magazines which defined men in terms of their masculinity.1

However, the woman’s magazine like other ‘feminised spaces’, including women’s studies courses, hen parties and girls’ schools, also has a radical potential. Like them it may become a different kind of feminised space, one in which it is possible to challenge oppressive and repressive models of the feminine. As the following pages show, the potential mismatch between ‘femininity’ and historical women could be a source of power for those women, though in the context of gender inequalities this was rarely the case.

FEMININITY AND THE TEXT

This book arises at the intersection of two interdisciplinary academic projects, women s studies and cultural studies and I have drawn on methods and theoretical approaches evolved in both. Two key concepts which recur throughout the book, therefore, are ‘femininity and the ‘text’. Its implicit argument is that the meaning of both these terms and the relationship between them which is my subject must be situated historically. Indeed I want to resist the academic pressures to separate ‘theory and conceptualising from historical practice, analysis and narrative. Nevertheless a brief account of how I use these two key terms may clarify the argument and method of what follows.

In addressing ‘women’, the magazines I discuss assumed the tidy coincidence of gender and sexuality with the embodied self. These categories are utterly entangled in our culture and their relationship is constantly assumed as given. In the late twentieth century, feminist, gay and lesbian, and queer theorists and activists have argued that the mapping of femininity (that is appropriate social behaviour) onto female heterosexual desire, and of both onto biological femaleness, far from being natural is only accomplished by powerful social, linguistic and psychological forces.2 Moreover, that task is never fully accomplished. Early critiques of social construction which suggested that gender was imposed on a more basic sexuality and that the body at least was natural have themselves been subjected to the criticism that they deny the extent to which sexuality is an effect of discourse and the female body a product of the social expectations of femininity (see esp. Butler 1990, 1993).

Throughout this book I assume not only that the meaning of femininity was and is radically unstable but that its relationship to sexuality and the female body had to be constantly re-worked. I do not assume that the magazines imposed a socially constructed femininity on a natural sexuality or on already existing bodies, but rather that the meaning of these terms was dynamically related. Nor did this go on simply in the realm of discourse. The female body was materially shaped by the corsets, medicines and hairstyles which the magazines recommended. And these recommendations were themselves the products of economic as well as ideological imperatives, the need for the magazines simultaneously to insist upon femininity and to attract advertising from the makers of corsets and medicines.

At certain moments the radical instability of these categories and the slippages between them became obvious, as happened in the 1890s (see Ch. 8). However, that instability was endemic throughout the nineteenth century. Indeed, I would argue that the magazine as a form assumed the place it did in women s reading in part because it addressed this problem. It sought to bring into being the woman it addressed as gendered, sexual and embodied. The naturalness of this complex identity had to be insisted upon again and again precisely because it was so slippery, and for this the magazine which comes out regularly weekly or monthly over time is the ideal form.

Across these instabilities there were certain constants. The first of these is that ‘woman’ was always positioned as other to and deviant from a norm assumed to be masculine/male. The second was that this involved not just difference but also power and the third that the meaning of these categories was always worked out within particular material histories. This is crucial also for my second key concept, that of the text.

In defining the magazine as a text I am drawing on the Barthesian definition of the text as a ‘methodological field and site of interdisciplinary study’ (see Pykett 1990:12). I read the magazine neither as reflecting nineteenth-century culture nor as a place in which the ruling class or group imposed its ideology directly on subordinate groups. Nor do I understand the magazine as producing experience as an effect. The magazine as ‘text’ interacts with the culture which produced it and which it produces. It is a place where meanings are contested and made. For the way we make sense of our lives as individuals and social groups involves constant negotiations in which there is no single determinant (Cameron 1985:170). This process also characterises the making of meaning in the magazine.

There are, however, structures and power relations which shape those negotiations in the magazine as in the wider culture. The texts I discuss were structured by the technologies of print and paper-making, which produced them as material objects, and by the economics of the publishing industry, which produced them as commodities. Crucially, also, the periodical press was a literary formation. The magazine developed its own generic and linguistic conventions and its subdivisions, each with their own discourses and practice. Increasingly, also, it developed a set of visual conventions and techniques through use of illustration. These economic, technological and literary or visual formations were caught up also with the social formations and power inequalities of gender, class and nationality. Together these structured but did not determine the way readers and writers used the magazine to make sense of their society and of their lives. Above all this was a dynamic process and not static, as the metaphor of structures may suggest. Just as the meaning of femininity was always being re-made, so was the meaning and the form of the magazine and its conventions.

METHODOLOGY

Defining the magazine as text shapes the methodology of this book. Textual reading depends on close attention to particularities. This book is, therefore, organised around case studies in which I offer close readings of particular magazines. I chose these as representative or significant after extensive sampling of the hundreds of titles I identified in an extensive bibliographical search.3 The case study method has also provided a way of dealing with the sheer mass of material involved in a study of this scale. Such a method may more accurately be described as inter-textual than textual analysis, since it is impossible to decide what constitutes a single text when one is dealing with a serial which came out weekly for years. Each number of a magazine only makes sense as part of a field of other texts as well as a field of power relations.

Literary and social historians are used to turning to periodicals for evidence about the past. However, they have rarely treated them as texts in themselves, using them instead as repositories from which they can remove ‘facts’, expressions of ideas and ideology, or fictional work in prose and poetry. There are notable exceptions to this, scholars on whose work I have drawn heavily.4 However, I have found most useful methodologically the work by feminists writing about contemporary serial forms for women, particularly Janice Winship’s work on magazines and Tani Modleski’s on soap opera (McRobbie 1978a and b; Modleski 1984; Winship 1987).

Treating the magazine as a text involved me also in considering the way it developed as a form over a period of time. Despite its importance in print culture, literary scholars have not considered the periodical as a genre with its own history. Yet, like the realist novel, the magazine was a form with recognisable conventions which were re-worked over the years and should be studied along a span of time. I have, therefore, combined the case study with the chronological narrative. The case studies represent particular moments in the development of the genre over the period of more than a century and they are organised more or less chronologically. This enables me to discuss the continuities and discontinuities in the magazine’s development and to relate them to the making and re-making of gender definitions through time.

It is not, however, a simple chronology. Rather, I have used the case studies to construct an argument about periodisation. The book is divided into four sections but effectively I divide the century into three periods, so the last two sections of the book deal with the most important period—the 1880s and 1890s. The emergence of a strand of magazines specifically targeted at women was complicated and slow. In the first section of the book, which deals with the period from 1800 to 1850, I chart this process. The second section uses the Beeton’s magazines which flourished between the 1850s and 1870s to discuss the consolidation of that tradition in both middle-and upper-class reading. In the third and fourth sections I discuss how a diverse women’s press became established at the centre of popular publishing. Throughout, the development of the magazine as a text is intertwined with the changing meaning of womanhood. In the rest of this chapter I set out some of the ways this relationship is explored in the book which follows.

THE ENGLISH WOMAN OF THE MIDDLE CLASS

The woman’s magazine came into existence during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century when the press and gender relations were both caught up in the revolution which made Britain the first industrialised and urban society. Historians have long since noted the emergence from that revolution of group identities understood in terms of class’. It is only recently that feminist historians like Catherine Hall and Leonore Davidoff have argued that middle-class identities were constructed on the ground of gender difference and took one of two forms, that of the masculine breadwinner or the domestic woman (Davidoff and Hall 1987). Nancy Armstrong’s more radical argument concerns the textual production of the domestic woman in conduct books and novels (Armstrong 1985).

Women’s magazines were produced by and produced these politics of classed gender or gendered class. Because material conditions made regular purchase of even relatively cheap printed matter beyond the reach of working women, most magazines targeted the middle class and offered explicitly bourgeois models of feminine behaviour. Throughout the century, femininity was represented as hidden in the privacy of the home and in the female heart, analogous sites for the exercise of virtuous self-control.

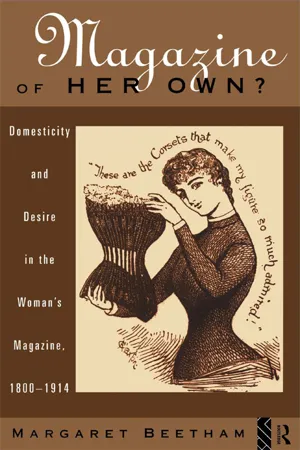

Yet this powerful discourse was constantly disrupted by others, particularly the discourse which vested femininity in appearance and located gender difference in the ‘natural’ difference of the body. The female body both as the mark of difference and as an erotic surface was always inscribed within the domestic. The biological difference of sex was marked culturally by dress. For most of the century men’s and women’s clothes were exaggeratedly different, not least because the curves of the female figure were emphasised through the use of corsets. The clothed female body represented in the fashion-plate became a staple of the periodical genre and the corset reappears again and again as a motif in this history.

The definition of femininity in terms of physical appearance alone was associated with an outmoded, aristocratic ideal but the biological and social necessity of female beauty proved a concept highly resistant to bourgeois moralising. In the discourses of dress, and especially in the illustrations, it persisted in middle-class magazines throughout the century and emerged in the 1880s and 1890s as a revitalised aristocratic model of femininity.

Since the nineteenth century defined itself as a class society, the relationship between class and gender definitions were often specifically spelt out in the magazines. The identification of femininity with ‘Englishness’, whiteness or Christianity by contrast only became explicit at particular moments. However, like those of class, these identifications were consistently assumed and constantly re-worked. The association of ‘true’ femininity with the English middle-class woman, articulated in domestic literature like Sarah Ellis’s Women of England series of the 1830s and 1840s, entered deeply into the tradition of women’s magazines (Ellis 1839, 1842). It combined with the evangelical tradition embodied in various mothers’ magazines which made an analogous identification of femininity with Christianity. All these fed into the more explicit nationalism and racism of the 1880s and 1890s when England’s imperial role was widely discussed.

Women’s magazines, unlike newspapers, were not published in provincial centres outside London. My research in one such centre, Manchester, has revealed no magazines addressed specifically to women and a number which assumed that regional identity was inherently masculine (Beetham 1985). Throughout the century, therefore, women’s magazines produced an exclusively metropolitan version of femininity. By the 1880s and 1890s women’s magazines were read across the empire but the identity offered in the magazines bound readers firmly into the culture of the capital. Even ‘provincial’ readers ...