- 112 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Communism and its Collapse

About this book

Ranging from the Russian revolution of 1917 to the collapse of Eastern Europe in the 1980s this study examines Communist rule. By focusing primarily on the USSR and Eastern Europe Stephen White covers the major topics and issues affecting these countries, including:

* communism as a doctrine

* the evolution of Communist rule

* the challenges to Soviet authority in Hungary and Yugoslavia

* the emerging economic fragility of the 1960s

* the complex process of collapse in the 1980s.

Any student or scholar of European history will find this an essential addition to their reading list.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1 What was communism?

Karl Marx told workers they ‘had no country’: in other words, they had a common interest more important than the national loyalties that might otherwise have divided them. In 1917 the world’s first socialist state was established in the USSR on the basis of his teachings. And for more than seventy years, latterly in association with a group of states in Eastern Europe and Asia, it was governed on the basis of Marx’s belief that human labour was the only source of wealth, that productive resources should be owned by the people as a whole, and that the working class in capitalist as well as socialist countries would recognise their common interest in a form of shared ownership that would eventually extend across state boundaries. It was the longest attempt that has so far been made to place ‘an ideology in power’. What, in broad terms, was this ideology? And what role did it perform in the states that were committed to it?

COMMUNISM IN POWER

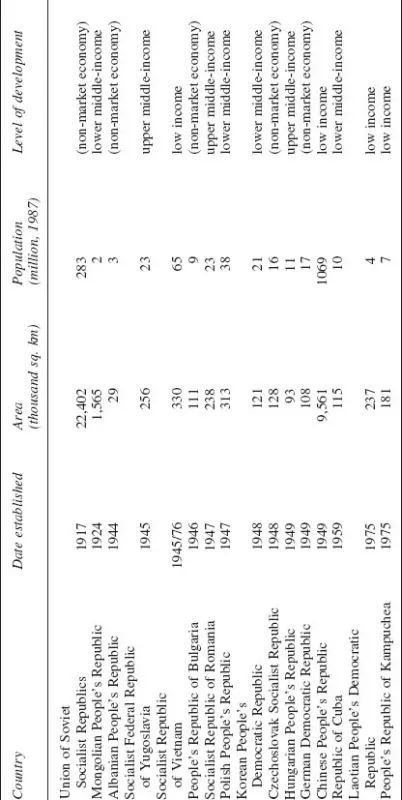

Until the late 1980s the USSR and the countries of Eastern Europe were ruled by communist parties formally dedicated to Marxism–Leninism. Together, they were known as the ‘socialist community’, and they formed a part of a wider group of communist-ruled countries that was officially known as the ‘world socialist system’ (see Table 1.1). The largest and longest-established of these states was the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR). Like its counterparts elsewhere, all aspects of public life in the USSR were dominated by a ruling party; and, as elsewhere, it was a single party that was committed to the establishment of a fully communist society. Under its constitution, the USSR’s highest goal was the ‘building of a classless communist society’; its political system was a ‘socialist all-people’s state’; its economic system was based on socialist ownership of the means of production of a kind that could not be used for personal gain or ‘other selfish ends’. Equally, although articles of everyday use and even a house could be privately owned, no form of property could be used to derive unearned income or in a way that was detrimental to the wider society.

Table 1.1 The communist states in the 1980s

Note: Levels of development and population are as reported in the World Development Report 1989 (New York: World Bank, 1989).

The Soviet authorities did not define the country over which they ruled as a ‘communist society’. Communism, in their view, was a state of affairs that would be achieved at an unspecified point in the future, when the development of productive forces made the distribution of goods to all in accordance with their needs a real possibility, when communist, collectivist values had been accepted by the population at large. Until that point was reached, the USSR and its East European allies were held to be more properly described as ‘socialist’ societies. In societies of this kind the means of production (factories, farms and so forth) had been taken into public ownership, and there was no longer a capitalist class that made a living from employing – or, in the official view, ‘exploiting’ – others. Equally, however, the state still existed (as it was not supposed to do under communism) and the distribution of rewards was determined by the work that people did, rather than by their needs. Only when the higher stage of communism had been reached would the state disappear and distribution be determined by people’s needs rather than by the work they performed.

In the Soviet case the single most authoritative statement of the official ideology was the Programme of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, a new and revised version of which was adopted by the 27th Party Congress in 1986. This defined communism in the following terms:

Communism is a classless social system with one form of public ownership of the means of production and with full social equality of all members of society. Under communism, the all-round development of people will be accompanied by the growth of productive forces on the basis of continuous progress in science and technology, all the springs of social wealth will flow abundantly, and the great principle, ‘from each according to his ability, to each according to his needs’, will be implemented. Communism is a highly organised society of free, socially conscious working people, a society in which public self-government will be established, a society in which labour for the good of society will become the prime vital requirement of everyone, a clearly recognised necessity, and the ability of each person will be employed to the greatest benefit of the people.

The achievement of a communist society of this kind was described in the Programme as the CPSU’s ‘ultimate goal’; the much more general transition from capitalism to socialism and communism on a worldwide scale was described, despite its ‘unevenness, complexity and contradictoriness’, as ‘inevitable’.

The 1986 Programme replaced a more ambitious set of objectives that had been approved in 1961 under party leader Nikita Khrushchev. This, the third of the programmes that the USSR’s ruling party had adopted since its foundation, was best known for its promise that a communist society would be established within twenty years. The construction of communism, the 1961 Programme promised, would be carried out in a series of stages. During the 1960s, the world’s richest and most powerful capitalist country, the USA, would be overtaken in per capita production, hard physical labour would disappear, the Soviet people would all live in ‘easy circumstances’ and the USSR would have the shortest working day in the world. By the end of the 1970s, the Programme declared, an ‘abundance of material and cultural values for the whole population’ would have been created, a single form of property – public ownership – would predominate, and the principle of distribution according to people’s needs would be close to attainment. By the end of the 1970s, the Programme went on to promise, a communist society would ‘in the main’ have been constructed in the USSR, to be ‘fully completed’ in the subsequent period. The Programme concluded with the words: ‘The party solemnly proclaims: the present generation of Soviet people shall live in communism!’

Not simply was this Programme not fulfilled; it soon became impossible to refer to it in public, and no more was heard of the dates by which its ambitious targets were to be achieved. Leonid Brezhnev (Khrushchev’s successor as party leader in 1964) introduced the rather different concept of ‘developed socialism’, which was a stage of socialism that would last for many years before a transition to communism could be contemplated. Brezhnev’s successors Yuri Andropov and Konstantin Chernenko (party leaders from 1982 to 1984 and from 1984 to 1985, respectively) made it clear in turn that the Soviet Union was ‘only at the beginning’ of the stage of developed socialism, and called for more attention to be given to immediate and practical tasks rather than what Lenin had called the ‘distant, beautiful and rosy future’. The Programme became increasingly out of line with these more realistic objectives, and in 1981 it was decided to redraft it. The drafting commission, chaired by Mikhail Gorbachev after his accession to the party leadership in the spring of 1985, brought this new version to the 27th Party Congress a year later. Officially it was just a revision of the 1961 Programme, but many, Gorbachev told the Congress, had suggested it should be considered an entirely new, fourth Programme because the changes it contained were so far-reaching.

The 1961 Programme, for instance, described itself as a ‘programme for the building of a communist society’; the 1986 version talked only about the ‘planned and all-round perfection of socialism’ with a view to a ‘further advance to communism through the country’s accelerated socio-economic development’. In 1961 it was assumed that socialism alone could abolish exploitation, economic crisis and poverty; the 1986 revision claimed only that socialism offered ‘advantages’ and that it was a superior form of society to capitalism. No dates or stages were given through which the transition to communism was to proceed (forecasts of this kind were ‘harmful’); and there were no references, as in the 1961 Programme, to the increasing provision of free public services, a guaranteed one-month paid holiday for all, or the withering away of the state – a classic Marxist goal (some had always maintained that the only thing that would ever wither away was the idea that the state should wither away). Indeed, there were few references to ‘communism’ of any kind in the new Programme; much more emphasis was placed upon eliminating defects in contemporary Soviet society such as profiteering, parasitism and careerism.

The new Programme presented an analysis of both domestic and international affairs. On the domestic front, the Programme put forward what it described as a plan for ‘social progress’ leading ultimately to the establishment of a fully communist society. The Bolshevik revolution of 1917 was held to have been a ‘landmark in world history’ that determined the main trends of development worldwide and launched the ‘irreversible process of the replacement of capitalism by the new, communist socio-economic formation’. The basic means of production had passed into popular ownership, industrialisation and collectivisation had transformed the economy, and a ‘cultural revolution’ had taken place that had led to the ‘development of creative forces and the intellectual flowering of the working man’. By the end of the 1930s a socialist form of society was held to have been ‘essentially built’ in the USSR, which had been fully and finally established after the defeat of Nazi Germany in the Second World War. A new stage began in the 1960s, when the USSR officially became a ‘developed socialist society’.

In a society of this kind, productive resources were owned by the people as a whole and there was rapid economic and technological advance. There were equal rights to work and pay, and a wide range of social benefits was available without regard to income. There was equality between the different social groups, between men and women, and between the nationalities, and there was ‘genuine democracy – power exercised for the people and by the people’ based upon the broadest possible participation of ordinary citizens. More generally, a ‘socialist way of life’ was supposed to have come into existence on the basis of the principles of ‘social justice, collectivism and comradely mutual assistance’. Further advances towards communism would take place (the Programme explained) as the economy became increasingly able to satisfy all reasonable needs and as the ‘truly humanistic Marxist-Leninist ideology’ became dominant. Internationally, at the same time, increasing numbers of countries were believed to be associating themselves with socialist principles as the ‘general crisis of capitalism’ continued to deepen.

TOWARDS A COMMUNIST SOCIETY

Clearly, if a fully communist society was to be achieved, there would have to be a series of related changes. First and most obviously, there would have to be an improvement in living standards so that all members of the society would be able to satisfy their reasonable requirements. But no less importantly, there would have to be a change in popular attitudes and values. Working people, for instance, even in a society that was based on public ownership, could still be affected by the ‘private property mentality’, and this might lead them to place their personal interests above those of the society as a whole or even to engage in black-market speculation and other anti-social activities. There was also the problem of nationalism. A fully communist society was supposed to be an internationalist one; that meant there could be no room for ways of thinking that divided working people from each other, to the advantage of their class opponents. A fully communist society was also supposed to be an atheist one, free of the ‘superstition’ that working people would find their ultimate fulfilment in a higher world and that the tasks of the current Five-Year Plan were not necessarily of greater importance.

For such reasons, the Soviet authorities and their counterparts in the other communist-ruled countries were committed from the outset to the development of a ‘new man’, one whose values and way of life would be appropriate to a future society in which there would no longer be class divisions. The Communist Party of the Soviet Union set out the characteristics of a new man of this kind in a ‘moral code of the builder of communism’ that was added to the party rules in 1961 at the same time as the new Programme was approved. The ‘builder of communism’, according to this statement, would be devoted to the communist cause, to the socialist motherland and to the other socialist countries. The builder of communism would also be committed to conscientious labour for the good of society (paraphrasing the Bible, the Programme made clear that ‘he who does not work, neither shall he eat’). The builder of communism would have a high sense of public duty, honesty and truthfulness; he or she would have an uncompromising attitude to injustice, parasitism and money-grubbing, and would at the same time have a fraternal attitude to the working people of other countries.

Every effort was made to ensure that these values were extended to the whole society. This was reflected, first of all, in a system of formal political instruction, intended primarily but not exclusively for party members. There were three main levels: at the primary level the subjects of study included the biography of Lenin and current party policy; at advanced levels there was more emphasis upon party history, economics and philosophy. By the late 1970s more than 20 million people were enrolled at the various levels of this system, and more than 30 million were enrolled in a parallel system of economic education. Beyond this there was a system of ‘mass-political work’, based on a network of more than 5 million agitators or lecturers who visited workplaces and residential areas all over the country to explain various aspects of party policy; and a further system of ‘visual agitation’, including the posters and slogans that decorated factories and other public places. Particular attention was devoted to anniversaries, such as 22 April (Lenin’s birthday), 1 May (May Day) and 7 November (the anniversary of the revolution itself); and there were campaigns on particular occasions, such as in the summer of 1977 when a new constitution was under discussion. Altogether, Brezhnev told the Soviet parliament, more than four-fifths of the entire adult population had taken at least a nominal part in the debate.

A special degree of attention was given to the rising generation. Schoolchildren were enrolled at the age of 7 in the Little Octobrists and then, at the age of 10, in the Pioneers. Finally, between the ages of 14 and 28, they could join the Komsomol or Young Communist League, the party’s ‘active assistant and reserve’, which enrolled about half the young people within the relevant age-group and helped to ‘educate [them] in the communist spirit’. The Pioneers, for instance, held meetings with veterans of the Second World War, and Old Bolsheviks; and they made regular visits to places of revolutionary significance, such as the cruiser Aurora in Leningrad that had fired the shots over the Winter Palace that had precipitated the revolutionary events of 1917. The education system itself made a further contribution. Party orthodoxy, for a start, was directly reflected in subjects such as history and geography, there were separate classes in civics that incorporated a simplified version of the official ideology, and the whole organisation of school life was designed to reinforce collective and cooperative forms of activity.

Still more important were the mass media, especially newspapers and television. A newspaper, Lenin had explained, was supposed to ‘educate, agitate and organise’, and all forms of the media came under the direct control of one of the departments of the party’s central apparatus. Editors were approved by party committees, and given weekly briefings about the themes they should (or should not) cover. Newspapers and other publications were subject to a close and detailed censorship, established on a ‘temporary’ basis just after the revolution and in existence throughout the vast majority of the Soviet period. The censor’s decisions were not made public (indeed, there could be no public reference to the existence of the censorship system itself), and they were not open to challenge. Television developed a national presence rather later, but by the end of the 1970s it was available to more than 86 per cent of the population; and it too reflected official priorities, with a strong emphasis upon the economic achievements of the communist world balanced by accounts of the deepening crisis of the capitalist countries.

The creative arts were also expected to perform an ideological purpose. Painting, for instance, was expected to be representational rather than abstract or allegorical; music was expected to have a recognisable tune; and novels were supposed to be optimistic in character, set ideally in a factory with an identifiable hero who should triumph in the end over the stubborn resistance of the class enemy. All of the arts were subject to the doctrine of ‘socialist realism’, first approved in 1934, in terms of which the ‘truthful, historically concrete presentation of reality in its revolutionary development’ had to be combined with the ‘ideological remaking and education of toilers in the spirit of socialism’. Soviet writers who satisfied these requirements, like Mikhail Sholokhov, were published in large editions and became extremely rich. Those who did not, like Alexander Solzhenitsyn, were prevented from publishing their work and could even be forced into emigration. And foreign writers openly hostile to communism, such as George Orwell, could only be read with special permission (their books, and those of political oppositionists like Trotsky, were kept in the reserve stacks of Soviet libraries and did not normally appear in their catalogues).

This, then, was an extraordinarily detailed and comprehensive system of political persuasion. And, for some, it had been an extraordinarily effective system. The Soviet authorities, certainly, felt able themselves to claim by the 1970s that a ‘new historic community of peoples’ had come into being who shared a ‘unity of economic, sociopolitical and cultural life, Marxist-Leninist ideology, and the interests and communist ideals of the working class’. There was, in fact, an increasing body of evidence that the campaign of mass persuasion had been less successful than party leaders had expected. Political lectures, it emerged, were often superficial and repetitive, they were attended unwillingly, and they tended to attract those who were already the best-informed and most committed – ‘informing the informed and agitating the agitated’, as a party journal put it. Relatively few, it appeared, gave any attention to the posters that decorated the street corners. Where they could, in the Baltic or East Germany, ordinary people turned to foreign radio or television, or to rumour and gossip, rather than the official media. And few read the editorial on the front page, which set out the party line.

Indeed, there were few signs, by the late 1970s and 1980s, that the communist society of the future was gradually emerging. There were far more religious believers, in spite of two generations of atheist propaganda, than members of the Communist Party. Young people, who held the key to the future, were becoming fascinated by Western pop culture. There was a flourishing black market. Crime was increasing in parallel, although the figures were not made available until the late 1980s. And ordinary workers were more interested in the bottle than in the fulfilment of the Five-Year Plan. Nor had there been much success with nationalism. It had supposedly been ‘resolved in principle’; but by the late 1980s there were open conflicts in several parts of the USSR, with the Baltic republics pushing for independence and a violent clash between Armenians and Azerbaijanis over the disputed enclave of Nagorno-Karabakh (see Chapter 8). Internationally, the world socialist system was resisting further integration, and communist parties in the wider world were losing much of the political influence they had once commanded.

The establishment of communist rule was none the less the central development in twentieth-century politics; and for more than two generations it defined a group of states that owed their...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Chronology

- 1 What was communism?

- 2 The establishment of communist rule

- 3 ‘National communism’ in Eastern Europe

- 4 The limits of reform

- 5 A system in decline

- 6 Transition from below

- 7 Transition from above

- 8 Explaining communist collapse

- Further reading

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Communism and its Collapse by Stephen White in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & World History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.