![]()

Part I

Framing Biosecurity

![]()

1

Introduction

Interrogating bio-insecurities

Kezia Barker, Sarah L. Taylor and Andrew Dobson

Introduction to biosecurity: defining biosecurity threats

A leaflet drops through your letter box advising on ways to avoid contracting and spreading swine flu. Your bag is searched as you enter a country on the start of your holiday – and there’s a fine of $200 for an undeclared apple. You drive across a disinfectant mat on a visit to a local farm. You call the council for advice on the Japanese knotweed (Fallopia japonica) spreading from your neighbour’s garden. You switch to eating organic free-range chicken after reading about the role of industrial farming in the production of avian flu risk. You shudder as you remember the smell of burning carcasses in the English countryside back in 2001. In many different ways you may have encountered events, practices, procedures, narratives and knowledges contained within the complex issue of ‘biosecurity’.

Just as Hajer (1995) described acid rain as an ‘emblematic environmental issue’ of the 1990s – an issue that functions as a metaphor for environmental problems at particular times – this collection demonstrates that biosecurity and associated issues, such as bioinvasion and nativism, are emblematic issues for the twenty-first century. This is because the study of biosecurity prompts reflection on a series of issues of great importance in contemporary society: the extension of security, selective territorializations against ever-increasing mobility, questions of localism and cosmopolitanism, the interaction of public and private domains in environmental management, and concerns over the construction of risk and the management of uncertain futures. Biosecurity provides a lens for interrogating these issues, and our response requires engagement from a host of disciplinary perspectives. This is what we aim to achieve in this book.

Across the social sciences, the burgeoning field of biosecurity studies, to which this edited collection is testament, is informed and driven by a number of theoretical currents. These include interests in governmentality and biopolitics (Collier et al., 2004; Cooper, 2006; Braun, 2007; Collier and Lakoff, 2008; Dillon and Lobo-Guerrero, 2008); questions of risk, uncertainty and indeterminacy (Donaldson, 2008; Hinchliffe, 2001; Fish et al., 2011); attention to nonhumans and co-produced networks, materiality, circulation and mobility (Clark, 2002; Ali and Keil, 2008; Braun, 2008; Wallace, 2009; Barker, 2010; Barker, in prep.); the interrogation of spatial processes of categorization and boundary-making (Donaldson and Wood, 2004; Barker, 2008; Tomlinson and Potter, 2010; Mather and Marshall, 2011); and geopolitical concerns with the interaction between nation states, processes of globalization, post-colonialism and modes of inequality (Farmer, 1999; King, 2002, 2003; Ingram, 2005, 2009; French, 2009; Sparke, 2009).

In some ways, crucial theoretical developments and new areas of enquiry have proceeded in a disease-driven way. HIV-AIDS, for example, has arguably marked the literature through attention to geopolitical concerns over the place of health in global governance as well as through questions of inequality (Elbe, 2005; Ingram, 2010). Scholarship emerging from reflections on the SARS epidemic drew attention to the globalized co-produced networks of disease exchange (Fidler, 2004; Ali and Keil, 2008; Braun, 2008). Meanwhile highly pathogenic avian flu has, through its construction as ‘the next big thing’, highlighted the future temporalities of disease governance, or what Samimian-Damash (2009) refers to as the ‘pre-event configuration’, the constellation of anticipatory discourses and practices through which biosecurity is enacted (Bingham and Hinchliffe, 2008). These diverse tendencies together demonstrate that no single theoretical lens is sufficient to fully encapsulate and respond to the critical issues raised by biosecurity, and reveal the capacity of biosecurity to act as fertile empirical ground for theoretical experimentation.

This combination of theoretical approaches, and the wide range of problem issues that biosecurity touches upon, makes it one of the most exciting and innovative areas of contemporary social research. The term itself, as Donaldson indicates, presents a ‘semantic banquet’ for geographers. ‘The evocative “bio” prefix brings to mind the “relational ontologies” and “hybrid politics” … encapsulated in performances of nature, society and space … whilst the “security” element resonates powerfully with contemporary geopolitical concerns’ (Donaldson, 2008, p. 1553).

For natural scientists researching biosecurity-related issues, the complexity resulting from interactions of physical, biological and human systems, and the ramifications of uncertain events such as climate change make this area of research challenging and enthralling. Increased computing power and the capacity of computer programmes such as Geographic Information Systems (GIS) to digitally represent disease or invasive species distributions, coupled with increased availability of remotely sensed data, have enabled scientists to analyse biosecurity issues on temporal and spatial scales that were previously impossible. Furthermore, predictions of species movements are increasing in accuracy as we get a better handle on bioclimatic-modelling (climate matching species’ needs; see Araújo and Peterson, 2012 for a review) and an improved understanding of the physiological and behavioural changes of target organisms in a changing environment (e.g. Huey et al., 2012). Amidst all this, the potential for scientific advances to be misused is a cause for concern (The Royal Society and Wellcome Trust, 2004). The National Science Advisory Board for Biosecurity, a panel of the US Department of Health and Human Services, makes recommendations on how to prevent biotechnology research from aiding terrorism without slowing scientific progress.

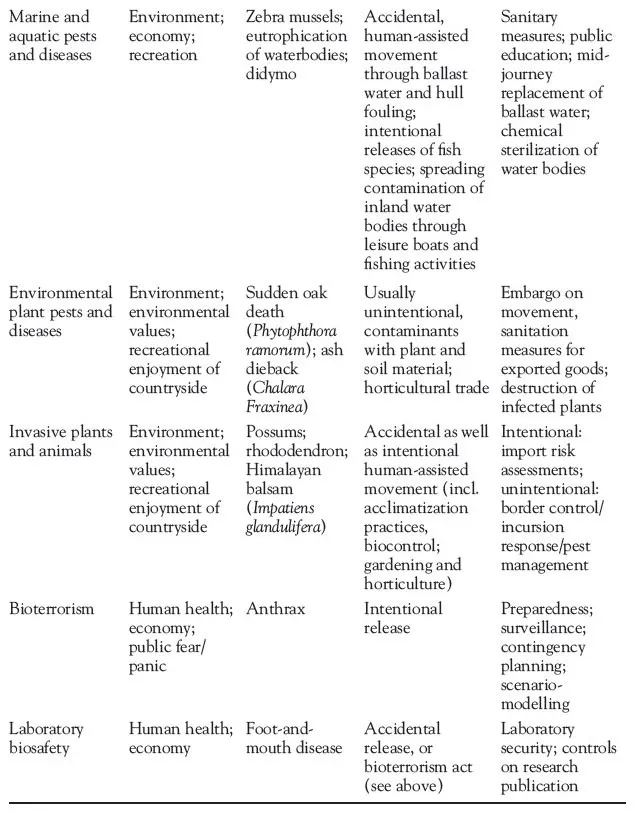

What biosecurity actually entails is itself up for debate, shifting across spatial, temporal and discursive contexts. Biosecurity can, in general terms, be described as the attempted management or control of unruly biological matter, ranging from microbes and viruses to invasive plants and animals. However, when delving deeper into the meanings and usages of biosecurity, it is immediately clear that variation exists in the term. The International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) provides an all-encompassing definition that places biosecurity within the domain of risk, describing a biosecurity threat as ‘matters or activities which, individually or collectively, may constitute a biological risk to the ecological welfare or to the well-being of humans, animals or plants of a country’ (IUCN 2000, p. 3). The term ‘biosecurity’ was largely unheard of in the UK prior to the 2001 foot-and-mouth disease (FMD) outbreak, during which it evolved from a reference to practices, such as cleansing and disinfecting, to the surveillance control of movement and spaces to stop the transmission of animal diseases within farming (Donaldson and Wood, 2004; see also Hinchliffe, 2001; Law, 2006). The latter led to enormous disruptions in both trade and tourism in affected areas (Irvine and Anderson, 2005). Internationally, in the post 9/11 era it has also come to be associated with the prevention of bioterrorism, laboratory biosafety and the spread of apocalyptic human viruses (Collier et al., 2004). Therefore three areas of concern mark national biosecurity regimes to a greater or lesser extent: (i) the protection of indigenous biota, (ii) agricultural assemblages and (iii) human health. This book encompasses consideration of each of these areas, drawing on a range of different examples and case studies.

In a national context, biosecurity takes on different forms according to its relative importance in regard to national concerns and vulnerabilities. For example, in America, biosecurity is understood primarily in terms of bioterrorism and laboratory biosafety. By contrast, biosecurity in Australia and New Zealand (as well as numerous island states) is driven by concern for native flora and fauna within an environmental conservation ethic, while in Britain and much of Europe the focus is on concern over agricultural assemblages and agricultural pests and diseases. These generalizations, however, belie important details. While New Zealand certainly has stringent environmental biosecurity controls and centres native nature within its national heritage, this stringency is exceeded by measures to control agricultural pests and diseases that threaten the export base on which the country depends. Furthermore, while bioterrorism has been the issue gripping political concern and driving investment in security technologies in the US, this threat has been mobilized in an attempt to make ‘naturally occurring’ infectious disease relevant to the agenda of policy-makers, resulting in ‘dual use’ surveillance technologies developed as ways of responding to both these threats (Fearnley, 2007). Finally, in the UK, the control of ruddy ducks (Oxyura jamaicensis), hedgehogs and grey squirrels (Sciurus carolinensis) was the subject of public political debate well before foot-and-mouth disease spread pyres of burning carcasses across our countryside.

These categories, of course, also overlap as invasive plants spread plant pathogens, as invasive animals introduce disease to agricultural domestic animals, and as a breach of laboratory biosecurity is dealt with as a bioterrorism event. It may in fact be more pertinent to note the ways in which the meanings of biosecurity shift across different sites and in different argumentative contexts, beyond these broader categories of ‘human health’, ‘agriculture’ or ‘environment’. In some ways more novel discursively than the practices it denotes (Donaldson et al., 2006), biosecurity can refer simultaneously to the mundane and the extraordinary, from precautions such as hand-washing and disinfection, to the spatial management of interactions between people, domestic animals and wildlife, surveillance webs of biocontrol and appropriate paper trails. What draws these different practices and concerns together is a shared construction of threat, posed by the ‘dangerous’ biological mobility of pests, viruses and other pathogens (Stasiulis, 2004).

Table 1.1 Examples of the range of biosecurity-related issues

In this interdisciplinary edited collection, we approach biosecurity threats as potential biological events precipitated, mediated, made visible, interpreted, politicized and brought into the realm of significance by social, cultural, economic and political factors (Wilkinson et al., 2011). Biosecurity discourses and practices themselves are not simply a response to disease or invasion events, but part of the process through which they are problematized and significance is brought to bear on occurrences. This perspective emphasizes the co-production of disease/ invasion and biosecurity policy response, as Stephen Hinchliffe argues in this collection: disease and pest invasions themselves emerge as relational achievements, ‘pathogenic entanglements’ between environments, human and nonhuman agencies. Importantly, this approach does not belittle the sometimes terrible reality of disease and invasion events – as crops are devastated, livelihoods are ruined and families are bereaved.

Biosecurity has risen to prominence in recent decades due to overlapping security concerns, new global frameworks for managing disease risk, which impact on trade and exports, and the accelerating and intensifying affects of globalization. It is currently high on the political and media agenda, not least following a series of ‘focusing events’ from SARS to H1N1, West Nile virus to foot-and-mouth, and through the ever present threat of a global outbreak of avian influenza. This concern is materialized in the allocation of greater resources for biosecurity, such as new integrated surveillance systems and networks of laboratories, and global agreements including the International Health Regulations (IHR) in the context of human disease. Are these biosecurity threats growing, alongside the increasingly high-pitched political and media concern? In one domain of biosecurity, Waage and Mumford (2008) analysed trends in trade and agro-ecosystem susceptibility and predicted increasing rates of establishment of new agricultural pests, but pointed to the limited evidence base due to a lack of research. They emphasize, however, that biosecurity burdens are inevitably growing overall, as new introductions accumulate.

The securitization paradigm

Many of the practices that contribute to biosecurity, as well as the threats from pests and diseases themselves, are far from being historically novel. So what marks out contemporary ‘biosecurity’ as a discursive practice affecting the ways in which the management of unwanted biological mobility – across agriculture, health and environmental management – is imagined, justified and conducted? The securitization of the bios has become the dominant response to uncertainty, globalization, rapid mobility and circulatory crises, and terrorism and insecurity. ‘Securitization’ practices in a host of different contexts entail ‘border controls, regimes of surveil-lance and monitoring, novel forms of individuation and identification … preventative detention or exclusion of those thought to pose significant risks [human and nonhuman], massive investment in the security apparatus and much more’ (Lentzos and Rose, 2009, p. 231). Critically, the governance of the future through a regime of uncertainty, urgency and threat is a distinguishing feature of securitization (Caduff, 2008; Anderson, 2010a, 2010b), allowing governance through states of ‘insecurity’ (Lentzos and Rose, 2009; Lo Yuk-Ping and Thomas, 2010; Brown, 2011).

Biosecurity issues have traditionally been analysed and administered through the lens of risk. Identifying and selecting between risky movements, and determining the level of appropriate intervention and investment in biosecurity measures, involves an industry of risk assessments, risk-profiling, cost-benefit analysis and bio-economic modelling. However, as risk analysis alone is no longer seen as an adequate way of responding to future unknowable events, biosecurity increasingly involves governing through uncertainty and insecurity. Uncertainty, defined by unknowable parameters, is inherent to responses to biosecurity threats and embedded in different biosecurity practices (Fish et al., 2011).

The cloak of uncertainty shrouding biosecurity threats shows itself in the condition of biological emergence, dynamism and indeterminacy (Hinchliffe, 2001; Clark, 2002; Cooper, 2006; Dillon and Lobo-Guerrero, 2009). Rather than a knowable list of historic pests and diseases, unruly biological life has come to be understood as emergent phenomena, presenting the continual possibility of new, unknown and unpredicted infectious diseases and invasive pests. An emergent threat, according to Cooper (2006, p. 124), is a threat whose actual occurrence remains irreducibly speculative, impossible to locate or predict, yet always imminent, the ‘not if, but when’. This ‘emergency of emergence’ (Dillon and Reid, 2009) focuses security attention on biological emergence itself, producing a state of permanent warfare against microbes (Lakoff, 2008a), or the targeting of ever-earlier points of intervention in the production of pests – such as the promotion of sterile garden plant varieties. This anticipation of species that have not yet materialized produces a transformed relationship to an unpredictable future which, as Anderson (2010a) highlights, both exceeds our present knowledge and disallows ...