eBook - ePub

Green Building Handbook: Volume 2

A Guide to Building Products and their Impact on the Environment

- 192 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Green Building Handbook: Volume 2

A Guide to Building Products and their Impact on the Environment

About this book

This key handbook provides a detailed reference for environmentally concerned purchasers of building products, and complements the Green Building Handbook Vol 1. Following the format of the original, this book discusses current issues in green building before moving on to consider eight building component types: fencing products, flat roofing membranes, glazing products, electrical wiring, adhesives, straw bale building, interior decoration and indoor air quality and ventilation. Invaluable for the specifier, this companion handbook will be useful to all those interested in finding greener ways of designing and making buildings.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Green Building Handbook: Volume 2 by Tom Woolley,Sam Kimmins in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Civil Engineering. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part 1

Introduction

The Development of Sustainable Construction

1

1.1

Changing Government Policy

An important consultation document was issued by the UK Government in 1998.1 Part of a wider consultation exercise on sustainability, it discussed some principles of sustainable construction and current practices in the industry. Following the consultation process, which brought in a relatively small number of responses, a Government strategy based on this consultation process will soon be published, though it is likely to fall well short of the standards advocated in this volume. While the government approach is hardly radical, recognition of the subject is a huge step forward and is to be greatly welcomed.

Other steps have also been taken, in particular the establishment of a scheme to provide one day’s free design advice to anyone planing to build a green building over 500 square metres. The Design Advice for Greener Buildings scheme is funded by the DETR and administered by BRECSU.2 This scheme demonstrates recognition of the importance of an holistic approach to consider all aspects of green building rather than simply focusing on energy efficiency which was previously the only area where financial help was available.

The construction industry has been under a great deal of scrutiny following the publication of the “Latham” report and more recently the “Egan” report.3 Both these reports recognise the inefficiency of the construction sector and the need to be more competitive and better managed. It is only in this economic sense that sustainability is usually referred to and the debate about the nature of building construction in the future largely ignores questions of environmental impact. Indeed the word sustainability only appears once, in the Egan report (paragraph 58) with a call for greater priority to be given in the design and planning stage to “flexibility of use, operating and maintenance costs and sustainability.”

While the UK lags behind, in some European countries, much higher standards and working practices have been adopted. These include the careful separation of waste on site into separate skips so that it is then recycled, the greater use of recycled materials in place of newly quarried aggregates and the elimination of many toxic and non environmentally friendly materials to improve building worker safety and improve indoor air quality. Most of these measures are covered by European directives and then enforced in particular countries by building or local regulations.4

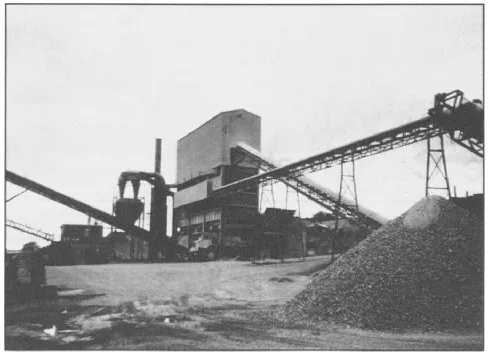

Fig 1: Conventional construction materials consume vast quantities of energy and raw materials, and pollute the environment.

Photo: Clare McCaughey

1.1.1

Demand for green materials?

At present most of these sustainability measures are barely on the agenda of the building regulation formulation process in the UK and there are strong industry lobbies to maintain the status quo for as long as possible. Many environmentally friendly products are now available in Europe, but few of them are sold in bulk in the UK. This is surprising in that many producers and distributors of building materials and products are multi national companies. Akzo Nobel, the Swedish company (of Nobel peace prize fame) for instance own many of the paint companies in the UK and are in the process of marketing these products under the name Akzo Nobel but it isn’t clear whether we can look forward to the introduction of Sweden’s higher environmental standards into the UK paint industry5

One argument that is used by building companies, designers and suppliers in the UK is that clients are not interested in eco products and so market forces continue to dictate that we continue to use materials that are not so environmentally friendly as they could be. There is some evidence of this in that when “Construction Resources” was set up in Southwark in London, the UK’s first eco builders merchants,6 many of their suppliers in Germany and Holland were unwilling to invest in the centre because their market research had told them there was little interest in the UK. In Germany, where there is even a federation of eco builders merchants, green materials have a significant share of the market.7

However this is something of a chicken and egg situation. Clients are frequently not told about green materials and even when they are interested, most materials cannot be sourced in normal ways, so if builders cannot obtain them from their normal suppliers they won’t use them. If designers promoted green materials and builders merchants stocked them, there would undoubtedly be greater use.

The public sector could give a lead in this respect so that local authorities, hospitals trusts and central government could adopt green specification standards and because of the bulk of materials which they order, the market would have to change to meet this demand. The Greening Government Section of the DETR has produced an excellent report which gives guidance on how to achieve greener buildings.8 Apart from covering most topics, under 38 headings, including indoor air quality, it has an excellent and comprehensive set of appendices giving sources of information and useful contacts. Needless to say, the Green Building handbook gets mentioned throughout. This document, which contains a Green Code for Architects (based on BREEAM),9 would be very useful to anyone trying to persuade a sceptical public sector client that green building is not a strange and hippie activity but quite normal and sanctioned by Government.

1.1.2

Timber Certification

As yet there are few materials and products which exhibit any credible form of environmental certification to the general public or specifier. Eco-labelling has virtually collapsed and the UK eco labelling board wound up.10 Only the certification of timber products has really become established. The Forest Stewardship Council logo (FSC)11 can now be commonly seen in many supermarkets and DIY outlets. The Forestry Industry in the UK is slowly moving towards the full adoption of certification which will be compatible with FSC, but there have been problems with the timber trade setting up rival schemes. A number of countries, such as Finland, have set up their own national certification scheme, but busy specifiers do not have time to check out each scheme or obtain the many hundreds of pages detailing the particular certification. Forests Forever, for instance is a Timber Trade Association campaign which advocates acceptance of this wider range of certification because they claim that some commercial interests will not join in with FSC.12 Some of their activity should be welcomed as they do promote FSC and the importance of using certified timber strongly. They produce a standard specification clause for architects and claim that they are producing guidelines for certification for the rival schemes to FSC. However a proliferation of such labelling can only cause confusion and be used as an excuse for those hostile to green specification to ignore it.

1.1.3

Public Interest in Green Building?

The general public has become much more aware of environmental issues through food scares, BSE, genetically modified foods and the abuse of anti-biotics and this has had a significant impact on consumption with supermarkets switching to organic foods. It is not clear why this public awareness has not yet switched to building materials and products such as these have just as big, if not bigger impact on our health and the environment. Organisations such as Greenpeace have had more impact on GM crop trials than they have through their anti PVC campaign13 and part of the problem can be laid at the door of the mass media. I have found it extremely difficult to interest radio, TV and national newspapers in green building, though there is a lot of interest from local radio. A proliferation of house improvement programmes on the television, have featured some green initiatives such as the Integer House (see section 1.4), but none of these have gone into the issues of green materials in any depth.

1.1.4

Environmental Profiling

Despite the lack of media interest it is only a matter of time before the issue of green buildings becomes topical or fashionable and then we need to ensure that a robust system of evaluation is in place before every product and material is repackaged as environmentally friendly. An important initiative which will contribute to this is the establishment of a an environmental profiling database for materials at the Building Research Establishment. This provides a methodology for materials producers to analyse the environmental impact of their products which are assessed against a wide range of indices. The development of the methodology was supported by 24 companies and trade associations and identifies and assesses the impacts of all construction materials ad components over their life cycle.14

Life cycle analysis is a complex and time consuming activity, but it is essential if you want to make a comprehensive analysis of the environmental impact of materials. Energy used, carbon and other emissions, disposal and re-use, all of these have to be analysed and calculated. The methodology can be made quite transparent but it must take account of many hundreds of factors and may appear to be complicated. Also all life cycle analysis has to include certain assumptions which are known as “Goal and Scope.” The analysis has to include certain parameters and boundaries and these are based on the use that will be made of them.15 While the number crunching in life cycle analysis is quite objective and scientific, the data that is fed in will largely come from the manufacturers. Their information about emissions and chemicals and disposal will often be seen as commercially confidential, so the data used will often have to be taken on trust. Of course, independent analysis of all the energy consuming and manufacturing processes can be done, but this is time consuming and expensive. Only when legislation requires companies to make all this information publicly available, with some kind of random, independent auditing procedure, can we be sure of what we are being told.

Also, as the BRE themselves state,

“A cradle to grave assessment appears at first sight to be the most complete and comprehensive and hence most justifiable. However…large numbers of assumptions must be made about the use phase of the materials and products over typically long time scales for buildings.”

Thus the environmental impact of materials and products is not just in the hands of the manufacturers but also the developers and managers of buildings and those who come to demolish them in 60 or 100 years time. Buildings are often refurbished and repaired several times and this must also be taken into account.

Underlying the development of environmental profiling and the interest of trade associations is the assumption that we should be constantly redeveloping buildings and consuming vast quantities of newly manufactured materials.

A deeper green position would question this materialistic approach and look for alternatives to using up so much of the world’s scarce resources, especially in the rich, developed countries. Natural and renewable materials could present one alternative and are discussed below.

1.1.5

Green Responsibility in Building Development

This raises another important issue about achieving green building, which is the need to make developers of buildings to accept a social contract of responsibility for the buildings over a reasonably long period of time. Many developers, whether they are financing office, factories or schools lose interest once the building is handed over and so there is no incentive to make the building energy efficient or last as long as possible. However some public sector private finance initiative16 projects are now requiri...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Part 1: Introduction

- Part 2: Product Analysis and Materials Specification

- Further Reading