- 304 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Finding Balance: Fitness, Health, and Training for a Lifetime in Dance gives an overview of issues faced by all performing dancers: injury and treatment; technique and training; fitness; nutrition and diet; and career management. The text includes both easy-to-read overviews of each topic and "profiles" of well known dancers and how they have coped with these issues. The new edition includes: Updated and new profiles. Expanded injury and injury treatment information. Updated dance science and physiology findings, and new references. Updated diet guidelines, Expanded and updated "Taking Control" section. It concludes with a list of selected dance/arts medicine clinics, a bibliography, glossary, and text notes.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Finding Balance by Gigi Berardi in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Dance. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Subtopic

Dance1

Dance

A Challenging Profession

KEY CONCEPTS/THEMES

Each dancer needs to find her or his place in the world of dance

Developing a positive self-image is the key to achievement in dance

All dancers need to learn to work with limitations

The science of dance informs the art

The dancer is a lifelong learner

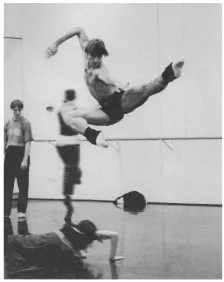

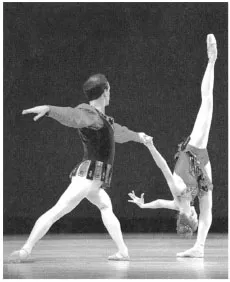

Dancers try to achieve the near-impossible. They aim for the ever-higher, bigger jump (Figure 1), with a picture-perfect landing. They strive for the full 180-degree hip turnout of classical ballet (Figure 2). They set their sights on precise, dizzying turns worthy of a figure skater.1

To achieve all this, dancers push themselves to the physical limit—in company class, in preprofessional schools, even in neighborhood studios. Few professional sports can compare with the demands that dance places on the body. As a prominent U.S. Soccer team physician, Bert Mandelbaum, puts it, “Dancers rank with elite athletes in terms of their need to compete and perform, regardless of injury and pain.… The psychological and physiological demands placed on dancers [elite and otherwise] are extreme.”2

While a top cyclist may exert an effort equivalent to running a marathon every day for the 3 weeks of the Tour de France, and a major-league baseball pitcher may be at serious risk for overuse injuries such as chronic elbow and rotator cuff tendinitis—at least they ultimately are evaluated only on their skill in achieving a result, not on their body type. Dancers, however, must conform to a predetermined idealized look, particularly in classical ballet. As clinical psychologist Linda Hamilton notes, “In a just world, dancers would be judged on their musicality, talent, and physical grace [i.e., their skill]. Yet the first thing the audience spots is—the body.”3

Figure 1 Gael Lambiotte of Dutch National Ballet rehearsing in the studio. (Photo by Angela Sterling)

Figure 2 Pacific Northwest Ballet's Louise Nadeau maintains full hip turnout, even in an extreme gesture — a deep penché arabesque from George Balanchine's Rubies. (Photo by Angela Sterling)

Of the millions of dance students and tens of thousands of semi-professional dancers in the United States, few have an ideal dancer's body. Even among professional dancers, the ideal physique is rare. Dancers face enormous cultural pressures to fit an ideal image. Dance students within just the normal range of weight, height, and anatomy can be at heightened risk for injuries as the body compensates for the physical demands placed on it.4 This includes even highly limber dancers, who may have an easier time achieving the streamlined, hyperflexible look but may be at risk for injury due to strength deficits. Young dancers, in particular, are vulnerable to overuse injuries owing to their developing musculoskeletal system.5 Ironically, a young dancer's greatest risk is at puberty, just as the intensity of dance training and performing increases and normal bodily changes undermine the ideal image of the thin, coordinated, flexible dancer.

Still, despite the risk of injury and the pressure to conform to some ideal image, the number of dancers is growing. By some accounts, more people are training in studios and participating in organized dancing than ever before.6 Although the numbers are less than, say, the more than 40 million people who regularly participate in softball leagues in the United States, including all the informal social dancers makes the numbers impressive.

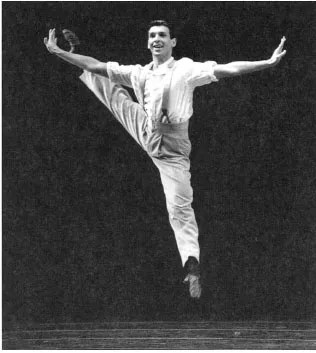

With so many dancers training, how many have an ideal body, or can expect to approach the technical brilliance of American Ballet Theatre's Ethan Stiefel or Pacific Northwest Ballet's Jonathan Porretta (Figure 3), the incisive performance quality of Roxanne d'Orléans Juste of the Jose Limón Dance Company or the buttery soft moves of Catherine

Figure 3 Pacific Northwest Ballet's Jonathan Porretta in Kent Stowell's Silver Lining. (Photo by Angela Sterling)

Cabeen of Bill T. Jones's group, the thrilling kicks of Ann Reinking or the enormous strength of Li Chiao-Ping and her Madison, Wisconsin-based dancers?

Author-physician Larry Vincent feels strongly that the ballet body is “born” as much as it is “created,” and perceives an artistic “Darwinian selection” that operates as a relentless survival of the fittest (or thinnest) in professional ballet. Especially in ballet, many of the “wrong” bodies for dance, as well as the less skillful, seem to fall by the wayside early in training—during childhood—leaving those with bodies better suited for ballet to continue on the path to becoming professional dancers.7 Social and world dance forms, as well as many schools of modern dance, may be more forgiving, but pressure on young people (especially at puberty) knows no boundaries.

Moreover, of the millions of dance students training in this country, few have been screened for anatomical vulnerability to injury.8 Instead, an implacable process of deselection is at work (which, in this country at least, ultimately weeds out virtually all dancers by middle age). Researchers note that only 5 percent of the children beginning a complete course of instruction at the School of American Ballet complete the 9 years of training; this attrition occurs because of various physical and psychological factors.9

Vincent argues, “If you re intent upon performing (regardless of level), recognize and accept your physicality, and work within your abilities. Find a type of dance or company that your body is best suited for, rather than attempting to overhaul your body.”10 Finding a place in dance where you can thrive is a recurrent theme in this book.

However much having a nonideal body type may hinder a dancer in her or his career, there is no doubt that anatomical factors play an important role in causing injury. For virtually all dancers, even those who are perhaps “naturally” stronger, faster healing, and free from structural deformations or anomalies, there is a need to know one's body and work within its limits.

Because of one's physical limitations, dance practice must be smart as well as repetitive. Of course it is important for dancers to practice movement, but not if they have structural anomalies that prevent its correct execution or if they make harmful compensations for limited muscle flexibility—and, most importantly, not if they don't know the intent of the movement or have a good understanding of which muscles need to be strengthened before a movement can be executed. According to the late dancer-choreographer Erick Hawkins, “You don't practice practice; you practice theory, based on principles of kinesiology.”11 Insights from theory on proper conditioning and training, together with good technique, can help offset the risk of injury and, even for gifted dancers, enhance and lengthen their careers.

This book contains the knowledge needed to guide conditioning and training, so that those who are captivated by the art and exhilaration of dance can have a full life in the practice of it. An important part of the book are the dancer profiles and the excerpts of interviews with professional dancers, first conducted from 1987 to 1989 and then updated from 1991 to 2004 for this second edition. These materials expand on and support the ideas about injury and injury prevention, training and technique, conditioning and fitness, and working within one's limitations that are the main message of this book.12

Good technique is not solely a matter of good genes (which is basically good luck). Neither is dancing injury-free. Applying what has been learned over the years in dance medicine and science can enhance the art of dance—both in developing good technique and avoiding injury. With sound training and conditioning, and selection of the appropriate dance form and dance company, dancers can find ways to work within their innate structural limitations and functional restrictions.

This was certainly true for dancer-choreographer Bill Evans (profiled in Chapter 3), who overcame physical limitations to become a renowned modern dancer and teacher. Says the 64-year old Evans:

For me, whether or not the dancer is born or made is really a balance between the two. I think the longer one continues to dance, the less it depends on the body you were born with. When I joined Repertory Dance Theatre, in 1971, everybody, including myself, considered me to have the least appropriate body for dance. But now, if you were to put me in a room with those same people, you'd say I had the best body for dance. Clearly, I've developed over the years. Sometimes those people with the [ideal] anatomy don't learn how to improve. When performance finally declines, they just give up. Never having the perfect body was a blessing. It allowed me to learn to dance.13

Access to information is critical to training and technique. In order to improve, dancers need information about how the movement is performed, including coaching for its intent. This must come from a teacher or other source (e.g., literature, videotapes) that the dancer respects and in a learning situation where the dancer feels safe. Some dancers are highly cognitive and analytical. They want to understand the physical mechanics of the movement they perform: how to find balance when turning, how to create the illusion of floating in the air, how to increase the height of a leg extension. For such learners, in particular, this book will be helpful. Dancers are voracious learners—the information in dance class is not enough; the learning process is lifelong.

In addition, recent information on dance kinesiology and physiology, although some of it is contentious, can help to debunk widespread negative images of dance. For example, although it is undeniably true that the female athlete triad (disordered eating, amenorrhea, and osteoporosis) is a concern in dance, studies show that dance actually may impart some benefits in terms of increased bone density.14

Thus, this book is intended for all those dancers and dance students who have ever faced challenging physical, emotional, or psychological problems—the vast majority of us—and are searching for information on recognizing, treating, and preventing injuries and managing their life in dance. The images and scholarly references in this book mostly refer to ballet and, to a lesser extent, modern dance, since these are the dance forms with which I am most familiar. However, the “lessons learned” from these forms apply directly to other social and world dance, tap, and jazz—wherever the show “must” go on and whenever technique such as above-average hip turnout (as in Scottish country dance) is desired.

Health professionals, teachers, coaches, and family members—the rest of the “team” who work and live with dancers—will also find this book useful. Finally, balletomanes as well as jazz and modern dance enthusiasts will find these insights illuminating in the world they watch so carefully.

Recognizing, treating, and preventing injuries is more fully discussed in Chapter 2. There the reader will find information about risk factors for injury, injury treatment, and rehabilitation including complementary and alternative medicine.15 Technique and training are covered in Chapter 3, conditioning in Chapter 4, and diet and health in Chapter 5. Developing a healthy attitude toward dance, especially finding one's place in the field, is the focus of Chapter 6, a new chapter in this edition.

In reality, most dancers make at least several career transitions. The dance world is large, and should be seen more as a sphere than a ladder—from coryphee (or apprentice) to principal dancer. The dance world is populated with teachers and students, artistic directors,lighting and scenic designers, musicians, press and marketing staff, costume managers, ballet mistresses, touring staff, development, marketing, and communications experts, health therapists, dance medicine and science practitioners, dance psychologists and nutritionists, dance writers and critics, and—last but not least—the dance audience. Finding one's place in the world of dance, a theme of this book, is discussed more in Chapter 6, as is making relatively smooth career or role transitions—within and around the dance sphere.16

An important theme of this book is that dancers are not necessarily “natural born,” but can be made—as long as a person has a strong enough desire to dance and has access to good training and information. The science of dance enhances the art and helps it develop. For many in dance, their work is a matter of learning to operate within limita...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Full Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- Acknowledgements

- Foreword

- Preface: Warm-Up

- 1 Dance: A Challenging Profession

- 2 Injury and Injury Treatment

- 3 Technique and Training

- 4 The Fit Dancer: Conditioning the Body for Strength, Endurance, and Flexibility

- 5. Nutrition, Weight Management, and Diet for Dance

- 6 Finding Balance: What Does It Take to Succeed in Dance?

- Appendix A Anatomy Basics

- Appendix B Dance Flooring

- Appendix C Feet First: Dance Footwear and Footcare

- Appendix D On Point

- Notes

- Glossaries

- Index

- About the Author